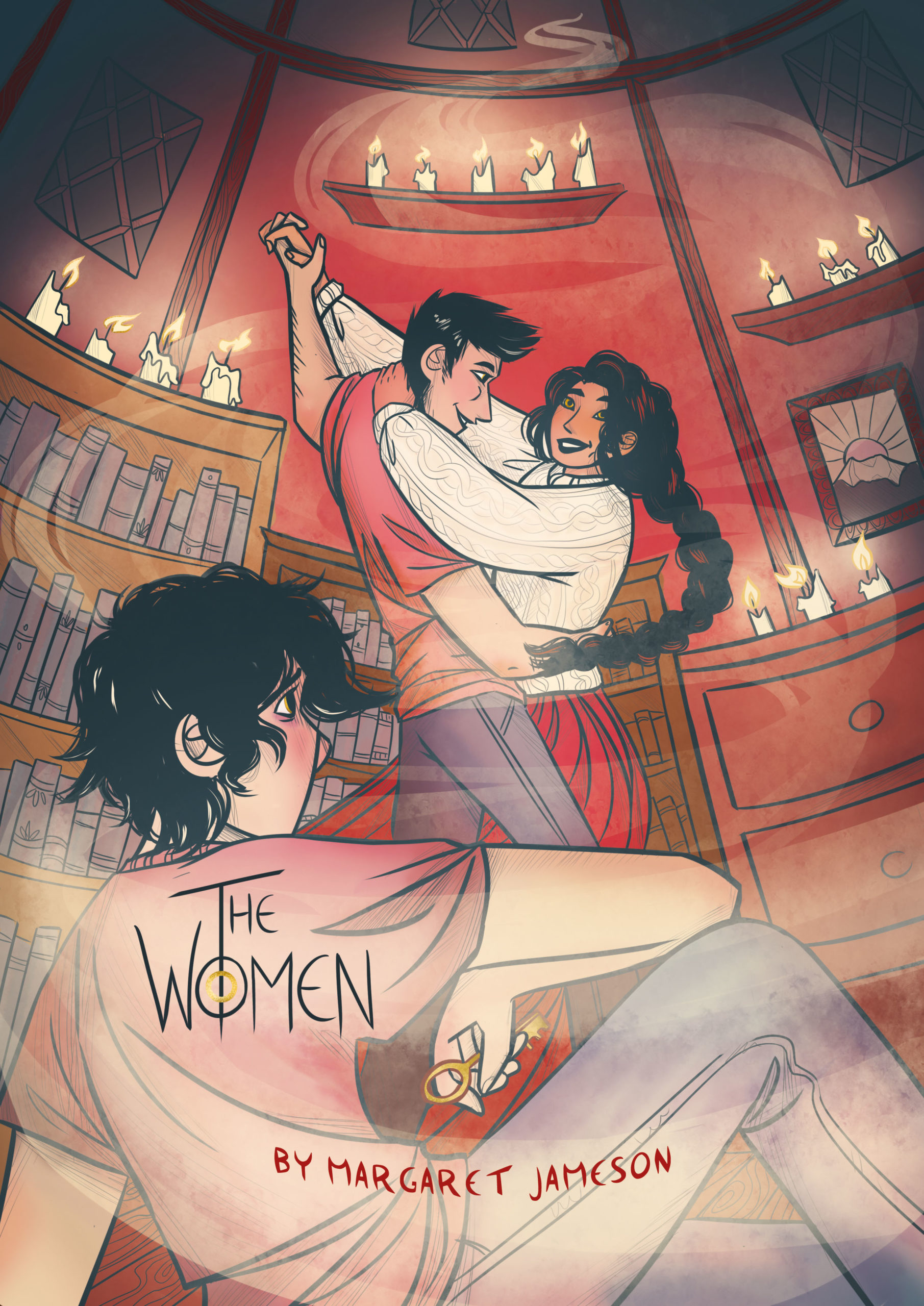

The Women

Words By Margaret Jameson, Art By Samantha Dow

I could try to bring you back. Your ghost I mean. Like the boy who conjured his father’s ghost in that scary little book Dad used to read us. Since you’re dead, and your memory’s all fucked up, you probably can’t picture it. Dad only pulled it out at night by the campfire. I’m pretty sure the cover said “THE WOMEN” in capital letters, and I know it was small enough to fit in his jacket pocket. There were lots of stories in there, for a skinny book. Each one started the same: “Not every Woman is a Witch, but every Witch is a Woman.”

You never liked to talk about growing up, but according to that book, “Remembering is the trick to Conjuring.” I’ve been blessed and cursed with a good memory, and now I’m going to use it, and the Spirit, whatever that is, to conjure you, Falk, big brother by six minutes, my one and only friend. TALK TO ME.

I’m not conjuring Dad. Never want to see or hear Henry again. Ever. Even if he did spend his life trying to save us. Even if he was right. I blame him for what happened to you, as much as I blame them. Stay away old man!

I bet you’re laughing. I must look pathetic—poking ghosts, tearing up Dad’s office with nothing but candles and kerosene for light. Still not used to life without lights, or a fridge that works, or AC. But I had to shut the power off. I couldn’t take the noise.

I know you were hearing it, months before I did, before Mina even showed up. For you, it was different. More gradual. It came on suddenly for me—wires in the walls buzzing, lights stuttering. Then Dad’s radio went satanic, and for a moment I thought it was Mina, and you two were back from New Mexico. But it was just me. The buzzing got loud. A swarm of buzz saws cutting, splintering. Sixty cycles per second, rippling my eardrums, my bones, my teeth. Chewed off my lips, almost. Christ, it got louder and louder ‘til it blocked out everything.

With no juice coming in, it’s a lot quieter. I hear things I never could before: ants in the backyard, current pulsing in the Markhams’ house down the road, cell tower signal hash. There’s an owl flying between the hickory trees out front. The witches in that book heard heartbeats through walls. They heard apples rotting, milk turning sour. Their eyes were shiny like mirrors, and they saw things invisible—dreams and secrets. They did a lot with mirrors. That’s how they changed shape, turning into owls and wildcats. They changed boys using mirrors too. They raised thunderstorms, made crops die and people sick. They made young men grow old.

Dad was scary when he did the witches’ voices. One night you asked him to stop, said the book was crazy. You made him real mad. He hated “that word.” Must be why he never told us the straight truth. He only spat out little clues, in his drunk, side-of-the-mouth, “you didn’t really hear that” way. Christ, those camping trips—five-hours from Delphi down to Ayahwasi Lake. He’d drive right through, wouldn’t stop to let us pee. One of us pissed our pants once. I want to think it was you, but it was probably me. You were always tougher, braver.

You asked Dad what happened to our mother. “They killed her,” he said. I started crying, but you shouted, “Who are THEY?” He whispered, “Hush. Or they’ll hear you. I’ll tell you when it’s time.” That time came too late. You were off with Mina, and I thought he was just being crazy old Dad, made crazier by a brain tumor.

Falk, I don’t want to believe he was right about them. He was wrong about everything else. Insanely wrong about girls. He must’ve read us that line, “Not every woman is a witch,” a thousand times, but he didn’t see a shiver of difference between “The Women” and just women. He thought all women were evil. Remember back in third grade, you brought Heather Felton over? She wanted to meet Cassius ‘cause she liked that picture of him you drew in art class. He was a real cute puppy. Cassius didn’t like Heather one bit. He barked and snapped, nearly took a chunk of her cheek. Dad hadn’t opened the place in town yet, so he heard her screaming. “You piece of trash!” he stormed. I was scared he was going to break off her little arm when he threw her out. “Don’t come near my boys again!”

Then Dad tore up your drawing, turned your backpack upside down, dumped your crayons everywhere. And he found the photo. Just a small sample print. You’re smiling, like some normal, happy kid. Dad shook it at us, like it was a bag of meth. “No goddamned photographs!” His ears went purple. “Do you want them to find you? Do to you what they did to your mother?” He cupped it in his big hand. Looked like he was going to shred it too, but he couldn’t tear apart your face.

You would’ve been that normal happy kid in the picture, if it wasn’t for Dad. Other kids liked you. Girls liked you a lot. It didn’t matter much for me. Girls thought I was weird, which was is true. Boys didn’t like me. No one but you and Cassius, and Dad, I guess. I want to believe Mina cares about me, and that she cared about you. Then I hear Dad—“Don’t trust her.” I hear that lawyer on the phone saying you’re dead.

When Dad was in the hospital, he said he wished he’d homeschooled us. But he couldn’t look at us all day, every day. We look too much like our mother. That’s why he sent us to Calvary after Heather and the photo. The tour answered his prayers (if Dad ever prayed, which I doubt)—girls in ankle-length skirts, boys in button-downs and khaki trousers. When Headmaster Hasselman said, “We don’t have any computers, not for the students,” I thought Dad was going to hug him.

We barely knew what a computer was, we were so deep in Dad’s bunker, living “the way men are supposed to.” All we knew about the rest of the world came from that portable radio he carried around, droning day and night. He kept it so low it was hard to make out what anybody was saying. Now I understand he wasn’t listening for the news. He was on alert for interference, breaks in the signal.

Unlike you, I wanted to go to Calvary. I thought I might make friends there. That didn’t happen. The teachers said I was “distracted and uncooperative.” Dad said my problem was I spent too much time reading in my room, not enough out in the sunshine. That was why I didn’t grow as tall as you, like we were trees or stalks of corn.

Dad stopped worrying about me after a few months. By then, you were making far more trouble. You were doing so well you stood out. Mrs. Gaither wanted you for the musical. Coach Finley begged you to try out for basketball and track. You pleaded with Dad to let you, you cried. It never mattered. Dad flushed so many permission slips we had to stop using the downstairs toilet. “No teams, no theatricals, no extracurriculars.” Later he added, “No goddamned parties!” That proscription only applied to you. No one invited me anywhere. Even during the summer, kids asked you to barbecues (and Dad said no). After he opened the office in town, you just told them you were too busy. Which was true. If we weren’t in school, we were working on the house—so Dad could show it off—or other people’s houses.

The only time we weren’t covered in sawdust was when we were down at Ayahwasi Lake. During that last trip, I sensed cracks in Dad’s bunker. You were real quiet, wouldn’t laugh at his jokes. I remember he was giving us his “old-man wisdom” by the fire—“Schoolgirls seem nice now, but soon they’ll be grown women. Women want one thing: power over men.”—you kept looking away, rolling your eyes. “There’s no trick they won’t pull to get it,” he went on. “A certain kind will do worse than trick you. She’ll destroy you. And this one won’t only be pretty. She’ll be the girl you’ve been dreaming of.” He drank a deep swig of Gosden’s bourbon and stared hard at you, and then me. “Just don’t look her in the eyes,” he said, still staring. “That’s how she’ll trap you.” The stare was weird. It was like he didn’t know us. Like we were strangers.

Then when we got home, and Dad bought the new truck, your attitude seemed to shift, like 180 degrees. We called it “the new truck,” but it was as old as the one we already had. I asked Dad why we needed another relic in the front yard. “You get something made after 1980, it’ll have all kinds of circuitry and computer systems. That’ll be a problem for you boys. This will last years and years. Anything goes wrong, you fix it yourselves.” He liked watching you work on it—polishing the trim, tapping smooth dents, cleaning the engine block. You put on a good show. Dad was convinced you were ready to live like he wanted. I can see him now, sitting in his wicker chair on the porch with Cassius at his feet. He’s looking over the Sunday paper at you bent under the hood, and a big smile is spreading across his face.

He was real happy. When you asked permission for that after-school shop class, he agreed instantly. Started talking about making us official partners—“Newell *and Sons* Quality Construction.” You were happy too and I knew why. You had a secret. Gabrielle. Remember her? You wouldn’t shut up about her soft skin and her cute nose. You said she called you “Angel Eyes” ‘cause of the gold rings—she called them “halos”—around your irises. My eyes have those same rings. Dad said we got them from our mother. Aside from Dad, no one ever noticed mine.

You and Gabrielle might’ve stayed together if you’d kept it under wraps ‘til we graduated. Dad promised we could make our own choices then. But she wanted to go to the prom. And since Dad was such an easy sell for the carpentry class, you thought he’d changed. You were wrong. Dad blew his stack. He wanted the name of the SLUT you were FUCKING. You told him to forget it. You should’ve known he wouldn’t forget it for one second. He called the school the next day and found out you weren’t in the shop. You’d never even signed up.

He exploded at me. I refused to tell him where you were, and he knocked me to the floor. I tried to yell, warn you when we pulled into the lot behind Crown Food. But my jaw was swollen shut. Dad walked right up to the truck, just as you and Gabrielle were really getting into it. He dragged you out. “You got yourself a big girl!” he shouted. Gabrielle tumbled from the passenger side—blouse open, face crunched, flinging tears. “I didn’t know you liked ‘em big, son. You want a brood of pups with that FAT BITCH? ‘Stead of the life I made for you?”

I think Dad realized he’d shaken the foundations more than he should’ve, but he did not understand he’d opened fissures that could never be sealed. He said he did it to help us. “You boys are men now, legally. I always wanted you to be pure, to be better than me. I’m just a man. You two are different. You might not see what I mean for some years. But if you marry one of these Delphi girls, she’ll see it.” He reached for you. “It’ll break her heart. Break yours too.”

You shook him off. “What the fuck made you hate women so much? Do you wish we were gay? Are you trying to make us gay?”

“Falk, you can’t make a man what he’s not, or a woman, or anybody. That’s where I went wrong. You’re boys, not angels. You can’t help it. You got half my nature in you, and I’m a very human man.”

“I wish you were a dead man,” you said. A loud stab blurted from the radio. I followed Dad’s eyes and saw the dial-light was dark. He hadn’t turned it on yet. Then a scream came through, the kitchen lights blazed, and I know Dad saw what I did when I looked at you—those halos around your irises were shining.

You tried to make up with Gabrielle, but she wouldn’t talk to you. Hisses of “Devil Eyes” followed you down the hall. It wasn’t just the end of your high-school Romeo career, it pretty much ended Dad’s contracting business. Gabrielle’s family were good church people, and they talked to other good folks. Suspicion had surrounded Dad since he first came to Delphi. No one had ever seen him at a Sunday service, or a food drive, or a town meeting. Whatever his reasons were for keeping to himself, for not letting his sons play basketball or socialize, they couldn’t be good ones. Soon, nobody wanted Henry Newell and his creepy boys fixing up their kitchens and bathrooms, building their decks, or repairing their roofs.

We graduated but didn’t go to the ceremony. We didn’t think about college. Dad needed us for the business, even though there was no business. He told us, “You boys got to work with your hands.” Seemed like our only choice. Beyond Delphi and Dad was a blank. We didn’t know anybody. We had limited skills. And sitting around Newell Quality Construction all day beat working fast food or retail.

By fall, the future had shrunk to a slit. Felt like the walls and the ceiling were contracting. Dad started getting headaches that his usual remedy—aspirin and a shot of Gosden’s—couldn’t cure. His hands shook so bad, he’d smash his thumb whenever he tried to hammer a nail. His vision got weird too. “Darkness is closing in,” he’d say. One night, he was parking the truck and hit Cassius. I thanked Christ the old dog lived. And that Dad was scared enough to see an eye doctor.

Which brings us back to Mina.

Dad thought she’d been watching us for years, maybe from the day we were born, waiting for the right time to enter our lives. We were alone in the shop, feet on desks—you reading gearhead motor mags, me reading James M. Cain. We had Dad’s radio on, the college station he hated. When she came in, the signal flipped and shrieked. The lights flickered. Cassius, who’d been nothing more than a heap on the floor since the vet prescribed painkiller treats for his hip fracture, suddenly woke and started barking. I grabbed his collar before he could lunge. She took off her sunglasses and smiled.

At first, I thought her eyes were just brown. Then sunlight coming through the window hit them and they went amber, ringed with gold. I must’ve looked like an idiot, ‘cause I stood and stared while Cassius strained my hold. I was so amazed—the color’s different, but otherwise her eyes are so much like ours, so unlike anybody else’s. It’s the halo at the edge of the iris. It glimmers.

Cassius snarled and drooled. Jesus, he wanted to kill her. “Your dog doesn’t seem to like me,” she said. She was so cool, not a note of fear.

“He’s old, and he’s never liked anyone, other than us,” I said while I dragged him into the storeroom.

You walked up and asked what we could do for her.

“I’m converting the old mill on Minosa Creek, and my contractor has moved on,” she said.

“We know the place. Used to hike up there.”

“Most of the work is done. Only the floors need finishing.”

“We can do that.”

She wanted us to start immediately ‘cause her furniture was coming from New Mexico. You told her we just needed to drive out and have a look—so we could give her an estimate—and we’d be on the job in the morning.

I picked up the keys to the truck. “I’m ready.”

“Lev, I’ll go.” You took the keys from my hand. “You got to meet Dad at the doctor’s.”

When you said that, it felt like you’d slugged me in the gut. I admit, I’d envied you some, wished I was the tall, good-looking one. But I’d never really been jealous before. I’d never wanted the attention you got. I didn’t care about Gabrielle or any of those girls at Calvary. I was fine hooking up with Raymond Chandler and Henry Miller. Mina was different. I wanted her attention. Being with her—that was who I wanted to be.

The doctor said there was nothing wrong with Dad’s eyes. The problem might be in his brain. Back at the shop, Dad didn’t want to talk about it. He was too worried you weren’t there. I told him you were on-site with a client. He knew it was a woman. “I can smell her.”

“I can’t smell anything,” I said.

“There’s a charge in the air . . . like before a storm.”

He asked where the dog was. I’d forgotten about Cassius. I turned the knob to open the storeroom and felt a weight against the door. I pushed and looked in. My throat closed up. Cassius was dead. His fur swept the floor as I shoved him aside. Made me think of a dirty mop. I put him in a garbage bag and laid him in the back of Dad’s truck just as you were driving up. You didn’t notice my eyes were red, or that Dad was slumped in the passenger seat, covering his face. “We got a job!” You held up your hand to slap mine, then lowered it when you finally looked at me and saw the bag. “That Cassius?”

We dug a grave in the backyard, and Dad poured us each a shot of bourbon to say goodbye to our old friend. When we went inside, we didn’t talk about the dog, or Dad’s vision, just our new client. You tried not to show how excited you were, but Dad and I could see it. You beamed as you described how Mina had converted the old mill into a self-sufficient-home-slash-ceramics-studio. She’d knocked out walls, exposed rafters, installed a new high-tech waterwheel, built a wood-fire kiln that doubled as a hearth. We were lucky the former owner had poured concrete on the oak floors, so Mina could hire us to remove it.

Dad didn’t like the job. “Tell that woman she can find someone else.”

You said it was too late. She’d written out a check.

Dad said he’d return it, and it wasn’t up to you.

“It is up to me!” you shouted. “I don’t need your stupid business. If you send back the check, I’ll go right to her, offer my services on my own. Then I’ll get paid, get my own place, and get the fuck away from you!”

The kitchen lights burst. The floorboards heaved under our feet. I caught Dad before he fell. Watching you stomp into the hall, I realized Dad’s bunker had crumbled like rotten fiberboard.

“Lev, tell me what she looks like.” Dad gripped my arm as I walked him to bed.

“Tall. Dark hair.” I lowered him onto the mattress. “Nice clothes.”

“What about her eyes?”

“They’re brown.”

“Just brown?”

I wasn’t going to mention the halos, but that slug you gave me still ached. “At the edges, they’re gold.”

Dad breathed deep. “I know about this woman, and I’m telling you she could be the end.”

“Come on, Dad, you haven’t even seen her.”

“She’ll destroy us.”

“I’m tired. I got to get to sleep.”

“Falk won’t listen, but Lev, you got to hear me. Don’t trust her.”

Before we drove up to the mill, I thought you were stretching the truth. Last I saw, the waterwheel was missing half its spokes. The creek flowed through without a single turn. I never could’ve imagined cypress and steel, churning day and night, metal blades flashing. “Hydroelectricity. Provides all the energy she needs,” you said, like you knew what you were talking about. I asked why we had to rent a generator for the sander to do the floors if the wheel was running. “It’s a non-conventional current, and this place isn’t wired like a regular house.”

The mill’s no regular house, that’s for certain. When I think of the fancy homes we worked on before, they all seem graceless in comparison. I like how the shadow of the floating staircase spreads like fingers across the floor as the sun passes over the skylight. I like the sound of the wheel turning and the water rushing past the rocks.

Neither of us wanted the job to end. After we finished the floors, we helped move in her things. I put away books—pottery sherd studies, illustrations of herbs and roots, grammar-dictionaries for Hopi, Amharic, Occitan—and dusted off old gramophone records—“Danza De La Hoguera,” “Death Sting Me Blues.” I wanted to stay there forever. Study all those weird books. Play every record.

On our last day, she asked us to stay for dinner. While I was out picking mushrooms, peeling belvoirs off a poplar, she came up and touched my shoulder. You’d told me what it was like when you shook her hand, but it was different feeling it myself. Pinprick pulses rushed up my neck, flickered under my skin. I smelled salt and fire. I turned and saw her eyes were shining.

We roasted the mushrooms with brook trout fillets on hickory planks. She served them over rice with a spicy red sauce in those iridescent ceramic bowls she makes. We had wine that night too. We’d never had any before. The clean taste brought out the sweetness of the spices and didn’t burn my throat like Dad’s bourbon. Light quavered in the sconces on the walls, making bright hexagons dance on my arms. My head felt fizzy, but good. We were all laughing. Everything was funny. Even I was, in a good way. Through the skylight, I saw the stars were bright, beautiful. Mina saw it too. “Let’s go outside,” she said.

We walked out the glass doors onto the rock ledge over the creek. The night sky seemed close, a ceiling above the Earth. The blackness was substance, pecked with countless perforations. Like a madman had drilled a billion holes through tar paper to reveal the light beyond.

Mina went up to the edge. “The stars make me think about time.”

“‘Cause they don’t change?” you asked.

“Everything changes. But those lights are very old and very far away, so change happens very slowly.”

“I want my life to change fast,” you said.

She looked at you. “It has. Already.”

The next morning, I stretched out my arms, and it seemed like I could reach farther than ever. Then I clutched at my gut. I felt a sudden churning, an emptiness, like a hole burning inside. A sour taste came up. I knew I was going to be cut out.

The night of the severing started sweet. A chill had set in, and Mina built a hickory fire in the hearth with herbs between the logs. I stretched out on the pillows and watched the flames. There were strange colors . . . blues and pinks. Smoke curled into floating spirals. The wine she said was real old felt heavy on my tongue, like liquid silver. But it didn’t slide thick down my throat. Just heat, brightness, lifting me.

Scratchy old jazz beats cut the smoke curls into sickles. I turned and saw you and Mina standing in front of the antique mirror by the phonograph. Mina asked you what you saw. “I look different,” you said. I saw it too. In the mirror, you seemed older. Not a kid. A man. I heard a clarinet, then a fiddle and a slapping guitar. The music sounded skinny but strong, like spider silk. You two started dancing. I’d never seen you dance. She showed you steps. You spun her around. Laughter and smoke stirred in the air, chords spread like waves. You and Mina twirled, almost swimming, wound in a whirlpool.

I felt pressure building. Lightning burst. Rain pounded hammerheads on the skylight. Anger shot me to the doors. Jealousy threw them open. I fell, sprawling onto the ledge. Around my fingers, rain splintered crystal, faceted, each drop a thousand eyes.

Mina came to me, halos piercing bright. She pulled me up. “Take the storm. Feel it rise.” There was red in her black hair. She took my hand and yours. Your eyes burned like hers, like mine. We rose, a circle of fire, liquid shards shooting off our charged skin.

I smelled the bolt before it split the sky. It hovered, crackling, suspended. The light that fills all living things.

Then you and Mina severed the circle, cut me out, and pulled each other close.

I woke up by the hearth. There was knocking on the front door. I looked out the window and saw Dad. It paralyzed me for a moment. He was the last person I wanted to see, but I figured I’d better let him in. Before I could, Mina came downstairs, looking freshly showered, and opened the door.

Dad had on his senior-style orange sunglasses and was shivering in the bright sun. “I’m here for my boys, Falk and Lev.” He winced as he spoke, like the words were cutting his gums.

Mina looked sorry for him. “Please come in.”

“Henry Newell.” He held out a shaky hand.

She took it. “Mina Wallis.”

Dad flinched and snapped it back. “Would’ve called first. Couldn’t find a number.”

“There’s no phone here.”

I was about to say something when you yelled from the top of the stairs, “What the fuck, Dad? How’d you get here?”

“Cob Markham gave me a ride.”

“Why? It’s Saturday. What do you need us for?” You seemed so relaxed coming down, though you were only wearing a towel around your waist.

“I have to get to Fairfax in an hour and a half,” Dad creaked. “Can’t see well enough to drive myself anymore.”

I’d blanked on his MRI scan. “Sorry. I forgot. I’ll take you.”

While I buttoned my shirt, you went over to the phonograph. “You ever see one of these, Dad?”

Dad stepped closer and squinted as you fingered the silver crank on the side. “Been a long while,” he said. “That’s a Gharinique.”

Mina joined you. “Built to last.”

“You know this music?” You put on the record you’d danced to. “From back when you were young?”

“Long before my time. How old do you think I am?” He glared at Mina. “A hundred?”

On the way to Fairfax, he asked me if you were sleeping with her. I told him to drop it. He wouldn’t. “I felt her power, Lev, I saw it in her eyes . . . She’s one of them!”

“Dad, who are they?”

“The Women!” he shouted. “The women who murdered your mother! If we don’t get him away, she’ll kill him!”

When we got home that afternoon, you were coming downstairs with a duffle bag. “I’m moving to Mina’s,” you said. “I can’t stand it here anymore. Can’t hear myself think.”

Dad collapsed on the couch. “Falk, give me a minute, please.”

“You got one second.”

“I see why you like her. She’s real pretty, sophisticated. Reminds me of your mother some. But, do you ever wonder why she’s here? Why come to Delphi? She doesn’t have family here. Doesn’t go to church—”

“She got sick of living in a desert. Thought she’d try somewhere green.”

“Son, you don’t know many secular young folks with their phones and their hookups, but think of yourself. If you had the money and freedom this young lady does, would you choose to live single in the backwoods of Virginia?”

“I would if I knew I’d meet her.”

“How did she know she’d meet you?”

“She didn’t!”

“Think, Falk! What’s a woman like her doing with a simple boy like you?”

“I’ve thought a lot. I know it doesn’t make sense. Mina could have anyone. I don’t know shit. You sent me to a school that wouldn’t allow computers. You wouldn’t let me play sports. I got no future worth anything, thank you very much. Despite that, for whatever reason, she likes me. We’re happy. And this time YOU CAN’T TAKE IT AWAY!”

A day or two later, the MRI results came back and they weren’t good. The images showed a ghostly corona in the right lobe of Dad’s cerebral cortex. He had a malignant brain tumor. If he wanted to fight, he was looking at multiple surgeries, immunotherapy, radiation, chemo. I didn’t think fighting was worth it. But I couldn’t sway him. He went in for surgery, which did more harm than good. Most of the growth couldn’t be removed without killing him, and in recovery, he contracted an intracranial staph infection. Spent his final weeks shuttling between the ICU and a rehab center that stank of piss.

I saw him every day. Sometimes he was angry, ranting—Mina was “evil to the core,” they had planted the tumor in his head. Other times he was calm, simply happy I was there. Near the end, he’d forget where he was, what year it was. He’d squint and ask, “How’d you get so big?”

You never showed up. It broke his heart. “Where’s Falk?” he kept asking. “Why isn’t he back from school?” I had to lie. “He’ll be here real soon.” The only visitor besides me was the pastor from Calvary, and Dad wouldn’t let him in the room. “Never liked preachers. You boys are what I believe in.”

He just wanted you and me by his side when he left this world. Right before his last seizure, he gripped my hand. “I know I made mistakes. But everything I did, I did to protect you.”

You and I never talked about it. That’s when the walls rose between us. We scattered Dad’s ashes in silence—half over Cassius’s grave in the backyard, the rest in the Shenandoah.

Then we got a surprise. We’d inherited money. Dad was from an old, rich family—the Gosdens of Kentucky (like the bourbon). He’d changed our last name to Newell back when we were infants. On the petition he filed, we saw our mother listed as “Barbara Saylor, Deceased.” Dad had never told us her name. Don’t know why, but from the moment I read it, “Barbara Saylor” didn’t seem genuine.

I went out and bought everything Dad forbade—cell phone, laptop, ultra-high-def TV, game console. I bought a phone for you too, since Mina didn’t have one, and you wanted to “stay in touch.” The old you would’ve really liked all that stuff. We would’ve watched movies and shows together, played games for hours and days. You would’ve helped me figure out dating apps. But while you packed one last load to take to Mina’s, I played Grimoire Assassin alone.

Mina drove over that night in her 1966 Gharinique coupe. (I think you were as hot for that old sportscar as you were for her.) I’d left Dad’s radio by the front door and before she even knocked, it was screaming. “Why’d you bring that piece of junk back from the hospital?” you shouted.

“Might want to hear the news!” I shouted back. The radio had been making little bleeps all morning (every time you walked past), but now sawed up, spiraling shrieks were coming through.

“Turn it off!”

“It is off!” I took it down to the cellar and yanked out the batteries, but it hollered on. So I muted it as best I could—wrapped it in a blanket, shut it deep in the cedar chest.

Back upstairs, the ceiling lamps were strobing. I heard stabs ripping through the TV speakers. You and Mina were in the living room, looking at Grimoire Assassin. The visuals and the sounds were all distorted—bands warped the screen, shredded howls echoed off the walls. Mina turned away. “I don’t like video games.”

Games or Mina. Though I would’ve made the same choice, it still made me mad. Playing with strangers online was fun, but I wanted to play with you. You tried to make up for it some, invited me to the mill a few times. Neither you nor Mina liked coming here. Too much noise. I regret that I kept to myself. I was trying to get my bearings. Everything had changed so much, so fast. I felt like I was falling, even when I was standing still.

I should’ve gone with you to New Mexico when you asked. Maybe I could’ve stopped you from going to the desert. There just didn’t seem to be room for a third in Mina’s coupe. “I got to stay and watch the shop,” I said. We both knew it wasn’t true.

“We’ll talk when Mina and I get back. I really want to talk to you, Lev.”

That was the last thing I heard you say.

It was a little over a month after you left that I woke up in the wrong house. I was here, this place I know better than anywhere, only it was wrong. The walls and the lights throbbed. Silver wrinkles broke when I touched them, then reformed—ripples, arcing around my fingers. Grimoire Assassin was all fucked up, just weird fractal patterns. Then shrieks came up from the cellar. It was Dad’s radio. I checked outside for Mina, for you, and saw nothing. I ran downstairs, pulled the radio from the chest, tore off the back. The batteries were gone, of course. But the thing kept blaring. I took it outside and grabbed the ax. Had to hack it to bits to make it stop.

I didn’t understand what was happening. I needed to talk to you. So I texted, I called. Got nothing ‘cept your voicemail. I started thinking I’d drive out West, surprise you and Mina. But I had no idea where in New Mexico you were going. I tried searching for “Mina Wallis” on the laptop, but the internet died and the keyboard got hot and the screen went black. Never came on again. My cell crashed before I got through to tech support.

It seemed the only way to find Mina, and you, was to break into the mill. So I drove there late at night. Just past the old rail bridge over Minosa Creek, the dashboard lights in the truck flickered out, the engine cut, and the wheels slowed to a stop. I got out and walked up the gravel road in darkness. Hot, heavy air stuck like syrup to my skin. Reminded me how long it’d been since you left. The nights were still cool then.

I grasped the handle to the front door, felt the lock catch and the bolt resist. But I wasn’t going to give up. I had to get in there. I thought of all the doors we’d installed, saw the lock mechanism in my mind. A bright coil whirled inside me, the hair on my arms rose, heat welled up ‘til my brain burned. Then the lock sprung, the bolt shunted back and the door swung open.

Inside, the air was cool. I smelled hickory ash, clay, dried herbs, old books. There were no buzzing wires or shrieking radios, just the soft lull of the creek and the waterwheel. I understood what you and Mina meant about our place being loud. I went over to the wall sconces, and before I could wonder how to turn them on, the filaments flickered up by themselves. Curving letters limned by the light spelled “Gharinique”—same as the phonograph, and the coupe, and I’m guessing, a whole other world of stuff.

Glinting hexagons scaled the walls and rafters as I searched closets, shelves, drawers, her desk. I found tins of tree sap, drawings of scary, spiky plants, but no IDs, address books, or letters. Not a single photograph. Aside from her pottery and some winter clothes, nobody would know who lived there. Just as I figured there was no point in staying any longer and was heading for the door, I heard a voice, whispering.

You don’t have to go.

It sounded like Mina.

This is your home, too.

Then it sounded like you.

I knuckled tears from my eyes as I slipped out. Felt like rising from the cool waters of Ayahwasi Lake into a steaming mosquito cloud. By the time I got back to the truck, any tears had boiled away. I was white-hot angry. How could you abandon me? Disappear for weeks when you knew what I was going to go through?

The truck started right up the moment I turned the key, as if my rage had jolted it back to life. On Route 50, I stomped on the gas. The headlights flared as I sped past 80 mph. Then I pulled into the Winchester police station. I was thinking they could get the New Mexico State Police to put out an APB or something. There were bright lights inside, though it must’ve been 4 a.m. Before I got out, I sensed the current. It was huge, saw-toothed, pulsing. Vomit filled my throat. I knew I couldn’t stand it in there for thirty seconds. And what was I going to tell them? You took off with your girlfriend and wouldn’t call me? I’d have to say I thought you’d been kidnapped, or worse. And they wouldn’t believe me. They’d think I was high and lock me up. I’d be raking my skull under those lights, losing it ‘fore they’d buy a word.

I drove home, went behind the house and shut down the main electric breaker. It was nasty hot without the air-conditioning, but it was much quieter. I slept in my sweat for eight hours. First decent sleep in days. When I got up, I tried using my cell to call you again. It was fried, no use. The landline still worked (I guess old phones don’t need current coming in), though the connection was bad. Your voicemail sounded crackly, like a recording from a hundred years ago. I left message after message. You never called back.

I hate that old land phone now. It’s cursed. If I just look at it, I hear hiss, crunched-up-words. A lawyer calling from Santa Fe regrets to inform me you are deceased. You had a cardiac arrest way out in the desert. Your body was medevacked to a hospital, but you didn’t make it. Though no known substances were found in your blood, an autopsy convinced the coroner that use of stimulants combined with a congenital heart defect caused your death. “Mina Wallis requests your permission to transport the cremains.”

I should’ve told that man his story didn’t make sense. I never saw you take any stimulants. If you did take drugs, why weren’t there traces in your blood? And how the fucking hell could you have been such a good athlete with a defective heart? Coach Finley said you were the best he’d ever seen.

It happened so fast. I heard myself say, “I grant permission,” before I knew what I was doing. If I hadn’t shut down the breaker, and the wires were still buzzing, I would’ve loaded the shotgun and sprayed my brains on the couch. Instead, I mourned the way Dad taught us. I went through the bottle of Gosden’s in the pantry in a day. Then I moved on to the case in the cellar. I slowed down by day four ‘cause it wasn’t helping me feel better. And I got freaked when I took off my shirt and it smelled like Dad had been wearing it. He was drunk a lot, I guess. But after that call from Santa Fe, his ideas about Mina and the Women didn’t seem crazy anymore.

Yesterday, I was sober enough to think. I started thinking about finding that book. Dad never allowed us in his office, so I figured it was the most likely place. When I opened the door, it was like he just left it. An insulation catalog lay open on the desk, next to a sticky shot glass. Not much inside the desk, only dried-up pens and an empty Gosden’s bottle. The filing cabinets had the real hoard. Dad kept our finger paintings, macaroni art, reports, even that third-grade photo of you that made him so mad. The rest was just old invoices and contracts, and porn. By sunset, I was going to give up. It’s hard to search in the dark. Then, in the far corner bottom drawer, under a stack of roofing brochures, I discovered some fascinating material—research papers on old religious sects, like the Shakers and Millennialists, plus a few describing Native American beliefs. All of them written by guess who?

Dad.

In the 1990s, he was Henry Gosden, graduate student of Cultural Anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. Shocking, right? I got out the storm lamp and some candles and thumbed through a couple papers. I read in this one, “Spirit Transference: Breaking Boundaries Between the Living and the Dead,” that a ghost world exists just beneath our feet.

It gave me the idea to take the whole file drawer out of the cabinet. Underneath, I found a snapshot of a young woman and a theater program. The photo’s scratched up and scorched around the edges. Can’t make out the face very well—her eyes are scratched out—but her hair’s reddish-brown, same as ours. The program is for a performance of “The Women,” a play by Clare Boothe Luce. Dad was the director. Didn’t see a Barbara Saylor in the cast or crew, and the one picture is no help—a black-and-white beauty parlor scene with everybody in helmet-hairdryers. Still, I believe our mother was one of the actors, or worked backstage. That’s how they met.

Back at Calvary, Mrs. Gaither never wanted me for her productions, but I remember the Drama Shelf in her classroom. I picked up a play called HARVEY once. I’d never read it, yet it looked familiar—thin paper cover, title in all caps, just like THE WOMEN. Dad didn’t read us scenes from a play though. There were no stage directions, or talk about hair salons, or much dialogue at all. He must’ve made up those witch stories, and used the play like a prop, to make us believe them more.

I was still searching this morning when I sensed a pressure change. The air smelled like salt and smoke. I looked out the front window and there was Mina, sitting on the porch in Dad’s wicker chair. I wanted to hit her. Crack her pretty skull. But I just opened the door.

“It’s quiet now,” she said, getting up.

“I shut off the power.”

Her fingers brushed my face. “The Spirit grows inside you.” Shocks went through my jaw. “I’m sorry about Falk.” She hugged me. I wanted to pull away, but the light was flowing between us. I needed to feel that.

She set your ashes on the counter in the kitchen and said, “No thanks,” when I offered Gosden’s. I poured a shot for myself. “Tell me what happened,” I said, staring out at Cassius’s grave in the backyard.

“I can’t.”

That’s when I swung.

She caught my fist before I knew I’d thrown it. My knuckles shimmered in her grip. Current raced up my arm, shot through my chest. Freezing, burning . . . I couldn’t move.

Her eyes shone like they did that night on the ledge in the rain. “I can’t tell you because I wasn’t there.” Then the halos dimmed. She let me go.

“How can you do that?” I was shaking.

She took my wrist and pressed. “Do you know why my finger doesn’t go right through your skin?” Sparks popped as she traced the inside of my arm. “It’s energy that separates us. Electrons winking on and off, binding molecules, lighting galaxies. There and not there.”

My blood turned hot fire. Light poured from my eyes.

“This is the Spirit. Everywhere and nowhere.” Her voice broke into harmonies, a song beneath her words. “All creatures have a spark, but in us, she is alive, bright and strong. Too strong for some . . .”

I jerked away. “You want to melt my brain too? Fry my heart? Like Falk?”

“No. I loved him.”

I held my arm. “Then why did you let him die?”

“It was his choice.”

“To do what?”

“To learn who he was! To face his legacy, our legacy, yours. It has been so for millennia, from mothers to daughters—”

“What about sons?”

“Sons are very rare.” She clasped my shoulder. The light curled and pulsed. “Lev, it’s time for you to learn who you are.”

“Don’t you mean what I am? What are we, Mina?”

She let go and stepped back. “I’ll return tomorrow morning. If you want the truth, you’ll come with me. Someone has been waiting to meet you. She’ll answer all your questions.”

I think “someone” is our mother. She’s alive. Maybe Dad lied to protect us, or ‘cause the truth was too strange, too painful. I guess it’s possible he didn’t know. She made him believe she was dead. Was she there in New Mexico when the Spirit cooked your heart? How the fuck am I going to make it, if you’re dust?

WHAT SHOULD I DO, FALK?

Sunshine’s coming in. I’m out of time. I hear Mina’s Gharinique on the main road. Think you hear that engine whirring too. You tuned it ‘til it sang to you.

You’re here. I feel it. No more walls between us.

Go with her. Face what you are. Then find your own way.

So that’s your answer. Risk everything, face the truth. You think, if I do it, and survive, they will let me find my own way to live? Not Dad’s way or theirs? If I die . . . That might be okay. We’ll both be ghosts.

I really wish I could find that book. Those words—“Every Witch is a Woman”—keep winding ‘round my head. I think I understand now why Dad wanted us to believe that. It was hard for him to accept his boys were what we are, and he didn’t want to leave it up to the Women whether we live to become men.