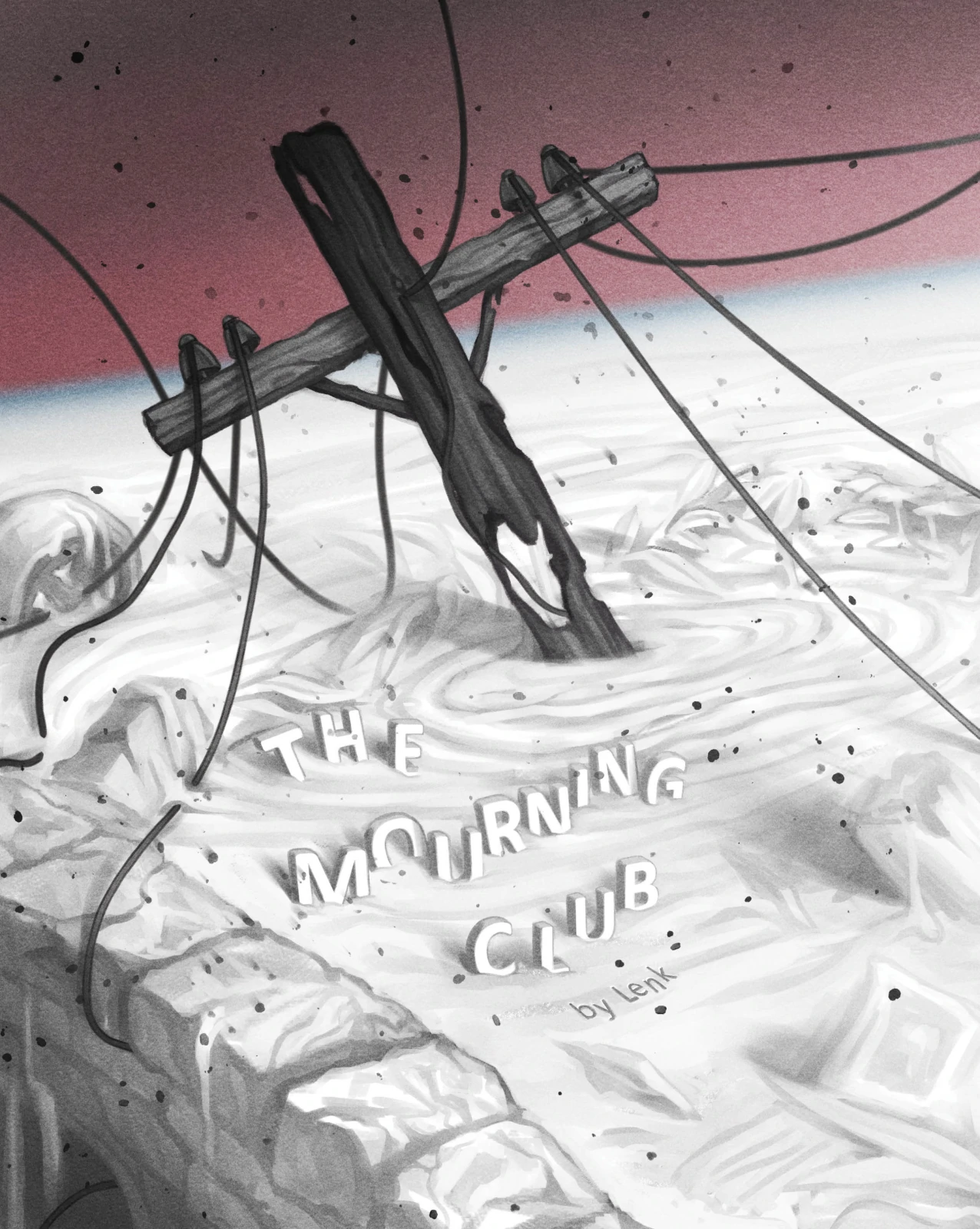

The Mourning Club

Words By Lenk, Art By Ejiwa Ebenebe

“What, are you nervous?” he asks.

“Well,” I shrug. It feels like the dark is pulling my voice out of me, unwinding it like a thread from my chest: “Kind of, Noel. I’ve never done something like this before—”

The shape of his hand presses warm into the small of my back. Not exactly comforting. Steadying. Holding still. “I’ve done it plenty of times! And it’s like—once you do it, you’re going to want to do it again. It’s—so fun. I mean, it hurts a little at first, but. You don’t even think about it, really.”

I can’t tell if it’s my ears ringing or if the night is pulling his voice away from him, too.

Are we fraying, then? Both of us?

Her name was Kendall Woods, which sounded like a housing development, but whether it was a trailer park or gated subdivisions with clustered cul-de-sacs and manicured hedges was unclear with just the name, so I had no idea what to think of her as my dad drove us to her place. Mainly because, for some reason beyond me—and I’m not a stupid kid—it was only in some fringe place in the back of my head that I actually believed it possible that she was my dad’s new girlfriend. Possible for us to walk into the surprisingly mundane little house, possible for them to greet each other with a kiss. No French cheek to cheek bises. No, smack of the mouths. And I thought: did he not tell me how close they actually were because he cares what I think, or doesn’t care what I think?

“Dinner’s almost ready,” she chirped, weaving this way and that in the kitchen, a blur of faded pink hair and goth fairy tattoo on exposed bicep. Edgy hippie, like Ren-Faire casual—sleeveless T-shirt of some metal band, swishing boho skirt, socks patterned like combat boots, pockmark scars here and there from childhood acne or childhood piercings—and I couldn’t fathom where my dad could have met a woman like her, let alone how in the world the two of them had even started talking. Kendall Woods.

“Oh my God, what is this?” Delighted, my dad plucked another appetizer off the plate Kendall had put before us on the coffee table.

“Candied salmon!” she said. “On sale at Freddie’s.”

“Kendy, you have outdone yourself. Out-done yourself.”

“Oh, stop.”

“Ben, what’s the matter? Oh, do you not like salmon?”

I was fighting a grimace about Kendy, but if I’d said, No, I don’t like salmon, it would have perhaps been just as rude, so instead I scrambled, “No, I—bit my tongue. My cheek.”

“I hate when that happens,” Kendall said as she brought our main course plates, then sat down with hers. Each of us, with our own small cut of (overcooked) steak, (over-) boiled red potatoes, and asparagus already chopped into pieces. “Itadakimasu!” she said, half serious and half not, and clinked her glass of saké with my dad’s.

“Kendall lived in Japan for quite a few years,” he said proudly.

“That was during my Buddhist phase.” Kendall laughed. “You want a glass, Ben?”

“He’s only eighteen,” my dad said.

“I will be in March,” I clarified, because I was still unsure of what I felt about being inevitably and irrevocably legal. Unsure if I felt anything, really.

“Well,” Kendall winked behind her glass at me. “My father was the same way.”

“If something happens,” I say, “if my parents find out, you’re fucking dead, Noel.”

He issues a little sigh and leans back, tossing longish hair out of his eyes. Last week, he dyed it red with Kool-Aid, à la Cobain. It’s still rather vibrant. I liked it better dark. “We’re all fucking dead, honestly,” he says. “Every day a little deader than the last.”

“Is this like your socialism kick?” I laugh, but it’s like the husk of a sound.

“No, nihilism. But, you know, Engels did have some damn good points.”

“Yes, you’ve said that before. Conditions of the workers.”

“Working class. Marx was almost there. Almost.”

“Yeah? Where’s your manifesto, then?”

“Ben, you still nervous?”

I don’t want to say, yes. But I am. I can taste my heart on the back of my tongue.

Noel looks at me full, the kind of looking that means he wants me to look back. His eyes like moonstones in the dark—bright, but also kind of haunting. “Ben. Do you trust me?”

I don’t know. My hands feel cold and hot at the same time.

“Benedict,” Kendall repeated, moving the syllables around in her mouth. There was a certain ASMR quality to her voice that made the back of my head tingle. “Like Benedictus.”

“No,” I said. “Just Benedikt, but with a k.”

My dad laughed. “Gotta have that Slavic k, you know?”

“You’re Russian?” Kendall looked to him in a way I didn’t particularly like, as if this were all so new she was still excited to find out things like that. Similar to my dad’s awe when she said things like I also lived in Germany for a while and I have a collection of haunted china dolls, yes. Giggling and elbowing like Holly and I did when we thought we were going to date.

“My mom was Ukrainian,” I said.

My dad reached for his drink. “His mom took a DNA test and found out her biological father was a Ukrainian freedom fighter, fled to America or something like that. She really took to the whole heritage thing.”

“Well, America is the melting pot of the world. It’s nice to feel like you aren’t just white bread.” Kendall winked at me like we shared an inside joke there. “Bene-dik-t,” she said again, leaning forward in kind of a mannish way, her elbows propped on knees pointed wide out.

“Really,” I mumbled, “you can just call me Ben.”

Okay, Ben, Noel had said when I told him that. Welcome to the Weird Names Club. It now officially has two members.

I didn’t understand how they fit together. It was slightly uncomfortable and very confusing. She worked in some warehouse or something—neither of them ever mentioned outright what, exactly, she did—and liked to garden barefoot in the middle of the night. She spoke very confidently about how she exorcised a poltergeist from her cousin’s house and once had a dog who was half-wolf, over whom she asserted alpha dominance in a minor wrestling match. Maybe it’s just that my dad, after years of working as a clinical psychologist, was tired of hearing normal problems from normal people.

I spaced out as we ate. It happened a lot recently. Suddenly Kendall was cleaning up our dinner plates—me sitting there awkwardly and my dad already blinking groggily into the horizon of pleasant satiation—as she said in that slow, whisper-magic tone of voice: “Ben, I do want you to know I’m not like, pretending she didn’t exist, you know? It’s tragic, what happened to her. I’m glad your dad is suing. A telephone pole shouldn’t topple over like that just because a car hits it. It’s a freak accident. It’s almost like, in this reality, her positive energy needed to be released back into the universe. A gift that she left for all of us. We’re beings of energy, you know. We all have energy in us.”

The papers—

1 DEAD, POWER OUTAGES IN FREAK CAR ACCIDENT

“You need to show him the pendulum trick!” my dad cried, suddenly more awake. He slapped my knee and I just gawked at him, wondering how he could let her talk about his dead wife like that. “You ask questions, and the pendulum moves to answer them. Isn’t that amazing?”

“I will, honey, I will,” Kendall hummed. “Listen, Benedikt—the universe needs that positive energy. It’s getting sick. Think about all the bad things that happen. Fossil fuels, genocides, pollution, raping the ancient forests of the world for condominiums and unethical coffee bean farming.”

The evening news—

AUTO ACCIDENT DOWNS LINES AND TAKES LIFE OF 1 DRIVER

I sat there squinting at her, trying to figure out if she was really trying to make me feel better by telling me my mother’s death was some sort of fucked up meant to happen. That it was a good thing. That my mother was a tree hugger’s messiah and going to save sea turtles from plastic straws and soda can rings.

“Kendy, Ben’s also into—what is it?” His eyes darted my way quickly.

“Ancient Rome?”

“Well, archaeology . . .”

“Oh, I love that!” Kendall cooed. “I make curse tablets for people. Etsy commissions. So, when you grow up, you want to be one of the guys discovering old bones and ruins and stuff?”

I nodded emphatically. “Have you heard of the Anemospilia?” Of course she hadn’t. “It’s the remains of this Cretan temple that’s the only real-ish evidence of human sacrifice in ancient Greece. There’s a room full of jars that have traces of blood on them, and one of the bodies by the altar, this eighteen-year-old boy, they found a sacrificial knife by him and they think maybe he was tied up or something, and . . .”

I was oversharing; I could tell. The waning focus in Kendall’s eyes told me she was struggling to keep up her initial amount of enthusiasm. Just nodding along like adults did with children. And I thought, maybe I would have done the same thing, if I were her, staring at this boring-looking kid with the weirdly-spelled name, who was slouched on her couch picking a loose thread on the Deftones patch DIY-stitched onto his borrowed denim jacket and talking about sacrificial knives and bloody jars.

“Anyway,” I said.

“The Ancient Greeks are the ones who diddled little boys, right?” My dad asked through a thrust of a chuckle.

“No,” I snapped. Little pause, flush of the cheeks as they both looked at me, startled. “I mean, yes? But also no.”

“Ben can speak Ancient Greek, too. Right?”

“I can recite the first line of the Iliad,” I mumbled. “Really not that cool.”

“They teach all this in high school now?” Kendall laughed. “Shit, we were lucky if they got us all to come to class sober. But that was the seventies for you, you know?”

“Well, his mom and I got him in one of those—” My dad held up a hand somewhere between the Italian pinch and pinky out, and it wasn’t a comment on my mom more than a comment on the school itself, “—frou-frou Classics schools.”

“A liberal arts academy,” I corrected him, for the sake of my mom as well as myself. “Classical education movement. It’s a lot to explain. Anyway, I’m going outside for a second. Be right back.”

“It really did a number on the wallet,” my dad was saying as I slipped out the front door, a little too early if he wanted to wait for me to be out of earshot. “Luckily, after the accident, he qualifies for a state-funded seat, because I don’t know if I could have kept him there otherwise . . . You know, he’s handling it all really well, I think, haven’t even seen him cry yet . . .”

At the end of Kendall’s gravel driveway, the cell signal was still flimsy. What was I waiting for? A text from Holly? From Noel? It was Christmas break. He was probably having Chinese for dinner with his dad in one of his dad’s many hotel rooms.

Sometimes I wondered if still smelling Noel on my fingertips—the denim jacket collar—was about pheromones or love, or if there was really any difference at all. All fucking chemicals, he’d have said, and he wouldn’t have been wrong. All fucking chemicals, and so is MDMA.

Fresh tobacco smoke blooms sweet and silky over the Deftones patch on Noel’s denim jacket. He hands the cigarette to me. I’m careful not to bite the filter when I drag, because when I do, it directs the taste straight to my tongue, which really makes my stomach flop.

“You remember what Aristophanes’ speech said about soulmates?” he asks. The cradle of his eye is still faintly black and blue from where Andrew Coleman clocked him last week, in the school hallway between Pre-Calc and Rhetoric III.

“No,” I say. “What?”

“It’s in Plato’s Symposium. Remember? Okay. So. At the very beginning of things, all people were actually two people fused together. These big, fat, four-armed, four-legged blobs that just rolled around having sex all the time. The gods were worried they’d get too powerful, so they split them all in half, cursing them for all their lives to be constantly searching for that other half they once had. And that other half is the soulmate.”

I stare at him. He turns his head to stare back at me. His bruised face dimples, his deadpan capsizes; he bursts into laughter. It’s contagious. I remember not to bite the cigarette filter.

“Are you still stoned?” I ask.

“No. Are you?”

“No. I think that’s why I’m nervous.”

“Stop overthinking it. Stop second guessing.” Noel takes the cigarette back for a long, ruminating, expert drag. “I promise you, you’ll like it. But—I’m not going to force you, either. The thing is, Benny, if you keep chickening out of every first time, you’ll never try anything.”

I’m not sure how, but by the time I got back inside, they’d moved on from discussing my education and emotional stasis to Kendall playing a gold-ringed snakewood flute with feathers dangling from a leather cord near the mouthpiece. My dad sat rapt on the couch opposite her, just watching her fingers move. Quietly, I took my coat off and draped it on the armchair, feeling very much like I’d just walked into the wrong movie theater, where a romance is playing that I’m not interested seeing, and there is no context, no before and no after, just the awkwardness of happening upon someone else’s story.

Kendall lit a new stick of incense and switched on the little tabletop water fountain near the couches.

“We’re going to do the pendulum trick,” my dad said, and never have I seen a man so indifferent to alternative spirituality get so excited for a New Age magic trick.

“Okay,” I mumbled.

It was all about energy, Kendall said again, a chunk of hematite on a little leather cord. She set out an empty glass and leaned forward on her elbow to dangle the stone just inside the rim of it. It was all about keeping the wrist slack and directing energy to the stone, she said. In her ASMR voice: “Clockwise.” The stone began to swirl clockwise. “Counterclockwise,” she said, and the stone slowly switched directions. “Stop,” she whispered. The stone stopped. “Two taps for Yes, one tap for No. Here, Benedikt. Hold my hand and ask a question.”

“Uh.” Her hand was warm and anti-aging lotion soft. I thought about it, mouth chalky.

Finally: “I don’t know—I guess, is Holly in love with me?”

Slowly, slowly, the stone began to swing. Harder. Closer to the glass. Tink. Tink.

“That’s a Yes,” Kendall hummed, and gave my hand an apologetic squeeze like she knew I didn’t like the answer. “Honey, your turn.”

My dad held her free hand now. “What is my middle name?”

“Honey, yes or no questions.”

“Oh—right. Am I jealous of Kendy’s cooking skills?”

Tink. Tink.

“You’re too sweet!”

“It’s true! That dinner was fab-u-lous. I mean, wow. I would eat it again. Right now.”

“No, it’s coffee and dessert time.”

She put on a movie. She and my dad on the couch half-snuggling, me on the loveseat pressing myself into the cushions like there was any chance of disappearing into them so I didn’t have to listen to their little comments and whispered dirty jokes that clearly indicated they’d already spent the night together at least once. I felt disconnected and uprooted, just sort of floating, there but not there, like that one Halloween night in eighth grade when it was just me and Noel huddling together for warmth in the public park bathrooms, swaddled in the white sheet he’d used for his Jesus costume, while Gustavo and Chloe dry-humped on the swirly slide.

“You know why they broke up last month, right?” Noel had asked me.

“Because Chloe went to some party and messed around with another guy.”

“But Chloe told everyone she’d woken up to him fingering her?”

“Yeah, I don’t know, man.”

I didn’t know, either. It had seemed in the tried and true tradition of sexual assault that no one knew whether to believe her or call it a cover up for cheating on the guy who was head over heels for her. Or it was just too hard for her to say. Like, “Why does Noel treat his dad’s friend Sherri like shit?” Because she (got him wasted one night his dad wasn’t home and touched him inappropriately) is a slut. Like, “Ben, why do you keep skipping class?” Because Mr. Talbot (always finds a way to bump our hands together and looks at me funny when I clean the board) is an asshole.

“Welcome to the Weird Names and Childhood Trauma Club,” Noel had said. “It officially has two members.”

Halfway through the film, my dad finally passed out like he invariably did after dinner. Kendall and I sat in a silence as tight and fricative as a playground Indian burn. But after we eventually exchanged laughs in shared acquaintance with my dad’s nap snores, she seized the moment to say, “You know, Ben, you can trust me. I’m not trying to replace your mother.”

I stared at her a moment, waiting to feel irritated. I felt nothing. Quietly, I said, “I know. No one can.”

And that was okay. Noel had said it, after his mom hung herself back in the summer between eighth and ninth grade. No one will ever replace her.

The difference is that his dad wasn’t trying to.

Maybe it is not a good thing to have things like that in common: dead parents and suspensions for fist-fighting in the school hallway.

Noel stubs out the cigarette. He scoffs, one of those half-laugh, almost-snort things I have finally come to understand are not at all cruel-intentioned.

“What, do you want me to hold your hand or something?”

“No,” I say, mildly insulted.

The film ended. The DVR reverted back to the local news channel. The sudden change in ambient noise woke my dad from his seventh five-minute nap, blinking frantically and looking between Kendall and me as if he thought we hadn’t noticed him sleeping.

“Why don’t you two head home?” Kendall cooed. “Ben, you should probably drive.”

“Thank you again for dinner,” I said.

“I’m okay to drive,” my dad said through a yawn.

“I’ll drive, Dad.”

“Let him drive, Henry.” Kendall smiled at me. “Are you a hugger?”

“Not particularly,” I said.

“Good. I was hoping I wouldn’t offend you if I didn’t hug you goodbye. It’s just I don’t generally hug many people. I absorb their energy too easily. Empath. And your energy is really low,” she added sadly. “Next time you come over, I’ll give you a nice cleanse. But—oh, actually, let me get you some cleansing bath salts!”

My dad laughed. “Oh, no, he’ll turn into a zombie!”

“What?” Kendall asked, looking back at us from the corner of the hall.

“Like the guy in Florida,” I replied.

“No, no, it’s just eucalyptus and mint. Be right back.”

My dad and I stood in awkward silence, this one with a friction not so much Indian burn as it was bruxism.

“She seems nice, Dad,” I finally said, hoping I didn’t sound as much as I felt like an actor who had forgotten his line was next.

“I told you, you two would really hit it off,” he said then. To my horror, his relief and excitement were genuine. It made me feel heavy. “I’m not going to lie. I’m really into her, Ben. I haven’t had someone who has made me feel this way in a long, long time.”

“You ready?” Noel whispers.

“I think so,” I whisper back. “If this hurts bad, I’m going to murder you.”

“If you don’t like it, I will be your personal slave for one week straight.”

“Wow, Noel, kinky.”

“No, dickwad. Homework, free rides to school, late night 7-Eleven runs—”

“What if I lie about it hurting just to get that deal? I really fucking hate Pre-Calc. And I like your bike.”

“Me, too. Honda Scrambler, baby. She’ll last me forever. Are you ready?”

“Yes.”

“Okay. Deep breath in, and as you go down, as soon as you feel it, breathe out.” He pauses. Then: “One . . .”

I breathe in. “Two . . .”

My pulse rushes in my ears.

“You trust me, Benny?”

“Yes, for fuck’s sake—”

“Three—”

We jump.

Just as our feet scrape and grit off the ledge of the bridge, Noel grabs my hand with a shout. Or maybe that’s me shouting. We’re both shouting. It isn’t a long fall. Just enough to send your stomach up through your spine, crush your thundering heart into the taste of metal on your teeth. We’re both flailing, instinct searching for purchase but there is no purchase, only air, and then suddenly there is water. I almost forget to breathe out at the impact. Noel, still clutching my hand, grinding the finger bones together as we plunge into a womb of bubbles, into the lightning pops of the cove’s bioluminescent algae.

We break surface scream-laughing and spit-gasping at the shock of the water so cold already, even for September. Water black in the nighttime but for those little sparks of light, that faint glow around splashing limbs.

“It’s fucking cold—”

Still his hand crunches mine.

“Go, go, go—”

Still he holds to it as we splash and stroke ourselves to shore, fighting against and stumbling under the sopping weight of wet clothes, up out of the water and onto the little cove beach. Staggering along hard gray sand, he holds my hand clammy and wet, then he uses it to turn me around and drag me over to him to kiss me full on the clammy wet mouth.

He doesn’t ask, so I don’t get a say. I don’t think I have anything to say. It’s sudden and almost possessive, rushed, impulsive, V-J Day in Times Square on a chilly cove shore under one of the freshwater bay’s low, stone, back road bridges. Noel’s hand starts to slip away before the tight-press shape of his mouth does, but I tighten my grip.

And, finally, I kiss him back, buzzing for the contrast between chill, slick skin and the heat of breath.

He parked his bike up the ridge from the water by the cove hiking trail sign. With bones still rattling, we change into the dry clothes we brought. We don’t talk about it. We talk about Latin III and Chemistry. About Holly and Veronica and Nietzsche’s genealogy of morality in conjunction with Cicero’s De re publica. We crest the hill of 45th onto Roosevelt and as Noel coasts his little motorbike to a stop outside my house, my dad comes blowing out the front door so half-dressed that he missed his fly and left his shirt untucked. He sees us rolling up, squished together on the narrow seat, and he says nothing about us not wearing helmets. The heels of Noel’s All-Stars tap-tap-tap the pavement as he wobbles his bike to a stop at the curb.

“Dad,” I say, “you didn’t lock the house up.”

“Get in—” my dad sputters as he jerks open the driver’s side door of his car. “Get in. We’re going to the hospital. It’s your mom—”

I swing off the back of Noel’s bike, my tongue already flattening itself to the roof of my mouth. “Sorry, what? What do you mean?”

The car starts with a violent flare of engine. I look to Noel like he has any explanation for this. He just leans forward on the handlebars, chin buried in folded arms. His eyes bright, haunting.

“Welcome to the Mourning Club, Ben,” he husks. “There are now officially two members.”

Kendall came back into the living room shoving forth ritual bath salts and some pillar candles dressed in pungent-smelling herbs. “Cleansing,” she said. “It helps, really. I promise. Soak in it for a good hour. Nice warm bath.”

“I heard therapy also helps,” I joked, but maybe it fell flat, because no one laughed. Not even me.

Kendall and my dad began their goodbyes—predictably cutesy, but alarmingly clingier than I’d expected. Cradling the candles and bath salts, I eased down to sit on the arm of the couch, trying to give them some space. Neither of them said I love you. I was thankful for that. On the television, footage of a church food drive for struggling local farmers—worthy of a Noel-grade maxim like Ah, the modern-day serfdom of farm-to-table—flashed abruptly to a faraway shot of the bridge over the cove—

“—in more somber news,” the news anchor with the too-blue suit was segueing in that round, bottom-of-the-chest way they all had, “a Ferne County high schooler died on Sunday after jumping from a bridge on Ferne Cove Drive—”

A closer shot of the bridge flashed on the screen. Low, stone, back road; teenagers staged laughing and horsing around near the wall of it, image of the walking trail sign on the ridge. My body went numb.

“Local law enforcement says, in the warmer months, many young people swim in the cove and have made a habit of jumping from the bridge, about a twenty-foot drop to the water—not even as steep as the high dive at the public pool—”

The world narrowed, tighter and tighter until it was nothing but a hollow vignette: me, the news, the strong-smelling candles and mason jar of pink Himalayan rock salt in my lap. Somewhere else in some other realm of existence, my dad and Kendall. You have to know the right spot, Noel had explained. To jump.

“The danger? There’s only a narrow margin below the bridge in which there are no underwater rocks. And in the winter? Water temperatures don’t go above fifty degrees. Friends say the boy was alone at the time—”

You don’t go alone, Noel had said. Never do dangerous shit alone. As I tried to maneuver my cell phone out of my pocket, fighting the slow choke of dread, a lavender-colored candle rolled from my lap, bounced off my shin and disappeared under the coffee table.

Maybe Kendall was right, and the world was made of energy, and the sudden surge of panic in me could produce enough power to strengthen the cell signal—somehow psychically will Noel to text me, pry a message out of the service towers or something. I’d be content with DO YOU STILL HAVE MY DEFTONES JACKET ?? after digging through a hotel room closet; in the fractal light of the television, forgetting to ash his cigarette: OLD MAN’S WASTED, I’M BORED, ENTERTAIN ME. Alone at the time, friends said. Alone and bored enough to sneak a fifth of his dad’s whiskey, alone floating at all the wrong hypothermic angles.

Telephone poles. Bioluminescent algae lighting up cold water. Closed casket funerals. Closed eyes. Mouths cold on the outside and hot on the inside. The telephone number on the fridge for a grief counselor no one was calling. A name like Kendall Woods. A reused B-roll shot of the bridge on Ferne Cove Drive blinked out. In its place, the senior photo of some guy who was not Noel, and all at once the sense of doom released.

You ready?

What was the opposite of capsizing, this falling-upwards feeling? All the underwater-nothingness breaking for a sharp breath—

Ben. Do you trust me?

“Ben?” my dad asked. “What’s wrong, kiddo?”

“Uh.” I turned my face into the Deftones jacket collar like I was wiping my nose and not my eye. “Nothing.” Just how confusing it was to finally cry, and not know about which part of it all. “I’m all right . . .”

“A candlelight vigil for Michael DiGeorge is scheduled to be held—”

The news sucked away into a ringing nothingness as Kendall turned the television off. “I know, right?” she said as I resurfaced from stretching under the coffee table to retrieve the fallen candle. “The evening news, it’s just all so negative!” Kendall sighed, shook her head. “I don’t like to let negativity into my house. You know? Leave your drama and your baggage and your tragedy at the door.”