The Hole in the Lake

Words By Isaac Marion, Art By Eric Schlelein

I still dream about the hole in the lake. I hover over it, suspended by the thinnest of threads, waiting to fall. There are monsters and currents flowing under the earth.

Do you remember the hike, Jake? The first time with just the three of us, you and me and Catherine? I think that was when we finally realized what we were doing. That moment when she came out of the water laughing, dripping, shivering for a towel. Everything in that moment was so symmetrical. The towel between us, Catherine in front of us, all equidistant.

Do you remember when she first appeared? You were nineteen and I was trailing two years behind. I bought cigarettes off you at five dollars a piece. I watched over your shoulder as the modem squealed and pictures of breasts materialized from the pixels. It was 1994, it was northwestern Washington, and the sun had turned Catherine’s skin to caramel.

“Who’s going first?” Mike said, and a nervous tremor ran through the group. “Kyle?”

I stared at the water below. A few kids inched to the cliff edge and looked over, then backed away, shaking their heads. We gave each other playful shoves and called each other pussies. Then Catherine, Mike’s shy little sister, just walked over and jumped off. Tucked herself into a slender blade, pierced the water and disappeared into the green depths. Her head popped up and she blinked water out of her eyes, grinning and gasping.

“Whooo!” she said.

Of course you were the next to go. You yelled some sort of battle cry, Geronimo or Banzai. You closed your eyes and you leaped.

They cheered for you. “Whooo!” and “Yeah!” and “Go Jake!”

You landed just a few feet from her. Could have broken her neck, but I was the only one who thought about things like that. When you surfaced, your faces were nearly touching; she screamed and splashed you and you chased her back to shore.

When the sun started to fail we headed back to the cars, tired and happy, damp and gritty with sand and pine needles between our toes. We piled into the back of Mike’s Jeep with Catherine squeezed between us. I remember the feeling of her arm against my naked ribs. The way it stuck there, warm and salty, peeling gently away when she shifted.

When we got home I asked you about her. Portentous questions like, “What’s the story with Mike’s sister?” You answered them with a blankness I found odd but not worrisome. You were my older brother. You were a different species.

Washington wasn’t prepared for that summer. A dry, brutal heat that shocked our rain-drenched bodies and emptied the Home Depot of its air conditioners. Skagit Valley Community College became a third-world country, men without shirts slumping against trees or pacing the square, fights breaking out over nothing. I sat at my desk in a puddle of sweat and thought about Catherine, letting the algebra equations in front of me blur into clouds of gnats. I spotted her sometimes on campus, her mouse-brown hair bouncing in a loose ponytail. She was young, but a different kind of young. Sweet sixteen and already out of high school, well on her way to an Associate’s degree through the Running Start program; I was older than her by the calendar only. High school dragged along behind me, clinging to my ankles like a half-dead animal.

You already had your degree, Jake; you had a job and a car and I envied your freedom. Wished I could advance time through sheer determination, somehow catch up to you and pass you. Those strange days when youth was a curse.

Slowly, subtly, we pulled Catherine into our circle. In the unbearable summer heat, regular trips to Whistle Lake were a necessity. The truth was I hated the cliffs, the blinding terror of looking over that edge, shutting down every natural instinct and jumping off. I know you felt the same, but we faked it and became the initiators, the ones who made the phone calls—five, sometimes seven days a week. Our friends’ greetings began to sound weary. The groups began to shrink. Eventually it was just you and me, Mike and Catherine, and then Mike got a job and it was just us.

I remember the first time we picked her up without Mike. Pulling up at her house in your Civic, me in the back seat like a taxi passenger because you said it’d be chivalrous. The cautious smile on her face as she climbed into the front.

“Hi, guys,” she said.

We said “Hi” at the same time, and I couldn’t tell if she heard me or if my voice blended into yours. I stared at the back of her head above the headrest, at the little blue clips holding her hair where she wanted it. We sat in the shade while she swam alone. We smoked Camels and munched Keebler pizza chips, watching the rippling shape of her legs kicking underwater. You pulled a beer out of your backpack and twisted off the cap.

“You have beer?” I said, amazed.

You grinned and handed me one. We sat in the dirt drinking the thin lager, watching Catherine climb up the cliff yet again. She seemed to genuinely love jumping. Even when there was no one watching, no one to think she was cool.

“Hide it when she comes back,” you said, and took a drink.

“Why?”

“She doesn’t like being around people drinking.” I looked at you. “How do you know?”

“She told me the other day when I was at Mike’s.”

“Oh.”

“I guess her dad drinks a lot.”

“Oh.”

Catherine flew down and slipped gracefully into the water. She emerged onto the sand, pulling her hair back, adjusting her bright blue bikini top, her tan stomach glistening.

“God, it’s cold!” she laughed, rubbing her arms, and we both jumped up. Grabbed for the towel between us like it was piñata candy. Our eyes locked, I hesitated—so briefly—and you got the towel. You handed it to her, and she wrapped it around her shoulders. She looked at you and said, “Thanks, Jake.”

It was evening when we dropped her off. She waved and we waved back. We were quiet on the way home.

“Catherine’s cool,” you said after several miles. You said it like an offhand observation, an inconsequential thought, but that was our language and we knew the meaning.

“Yeah,” I said, watching the yellow lines dart under the car. “I think she’s pretty cool too.”

Your head twitched like you were going to look at me, but you didn’t. We drove home.

When I found the hole in the lake, it felt familiar to me. As if I’d been there many times and had somehow forgotten. Glimpses lost in the wrenching and twisting of waking up, buried in the nauseous haze of old fever dreams. I thought of the morning we found out Mom had cheated on Dad when we were little kids. I thought of the night Dad shoved you into the fridge and all the magnets fell off, how your face hardened so much it scared me. Memories floated up from the hole like dead bodies loosed from their weights. The hole offered them to me, a grotesque hello.

I started to see more of Catherine at school and felt a tightening in my gut. At home you and I talked less. Undertones and overtones appeared in our voices. She called out to me from across the tiny campus and I waved. She ran up and hugged me hard. I saw my handprints on her back when she walked away, bleach-white on her blue Hypercolor shirt, and I wished the cool air wouldn’t erase them so quickly. Later she appeared in a new class and sat next to me. She kept smiling at me like my presence made her happy. I didn’t know what to feel.

When you got home from work you would ask me if I saw her in school and I’d say yes. Then you’d tell me you saw her at Mike’s last night and talked to her about going to the lake again. I’d tell you we walked over to the gas station and got lunch, sat under a tree drinking Clearly Canadian and talking about new bands we’d discovered. You’d nod and tell me you went on a walk with her outside her house. Talked about her dad. I nodded, but I wanted to scream at you that it wasn’t fair, that you were too old for her, that you had promised you’d never chase the same girl as me, that we were brothers and you’d sworn never to fight me this way. You saw it all in my face but it was too late now. We didn’t have control.

It was on our twelfth trip to the lake that I found the hole. We kept going back, taking our fight to the same arena over and over in hopes that something conclusive would happen so we could finally stop. You were ahead of me that day. You threw a twig into her hair and she smiled. You chased her on your bike and I chased her too, but you had a ten-speed and I had an eight. You caught up to her and pedaled beside her, grinning, and the baked earth coughed up clouds of dust that stung my eyes.

There in the forest, by the lake and the cliffs, you were sitting on a log asking if she wanted to see a movie that weekend. I thought I saw her touch your arm.

“Kyle?” she said as I walked off into the trees. “Where are you going?”

“Just looking around.”

She frowned. Her attention was all on me now. I walked away.

I hiked up the mountain for a while, then I went off the trail. Wandered through the trees, everything brown and parched in the scorching heat. Brittle underbrush scratched at my legs, leaving white lines in my tanned skin, sometimes biting deeper, drawing little sips of blood.

I walked out onto a high ledge and there it was. At the bottom of a deep mountain basin of dark evergreens and dusty rocks. A lake. Not Whistle Lake, not the cool green sea that welcomed our sweaty bodies on so many lazy afternoons. A different kind of lake. And then I saw the hole.

I hope you never forget our talk. That moment when I stopped you in the doorway and said, “Hey. I want to say something.” Mom and Dad weren’t home. We were alone in the house, tensed at the top of the basement staircase. Sure we were all just kids. Nineteen, seventeen, sixteen. But look what happened. The moment had weight we never imagined.

“Hey,” I said from the trees behind you, and you both startled. “Come look at this.”

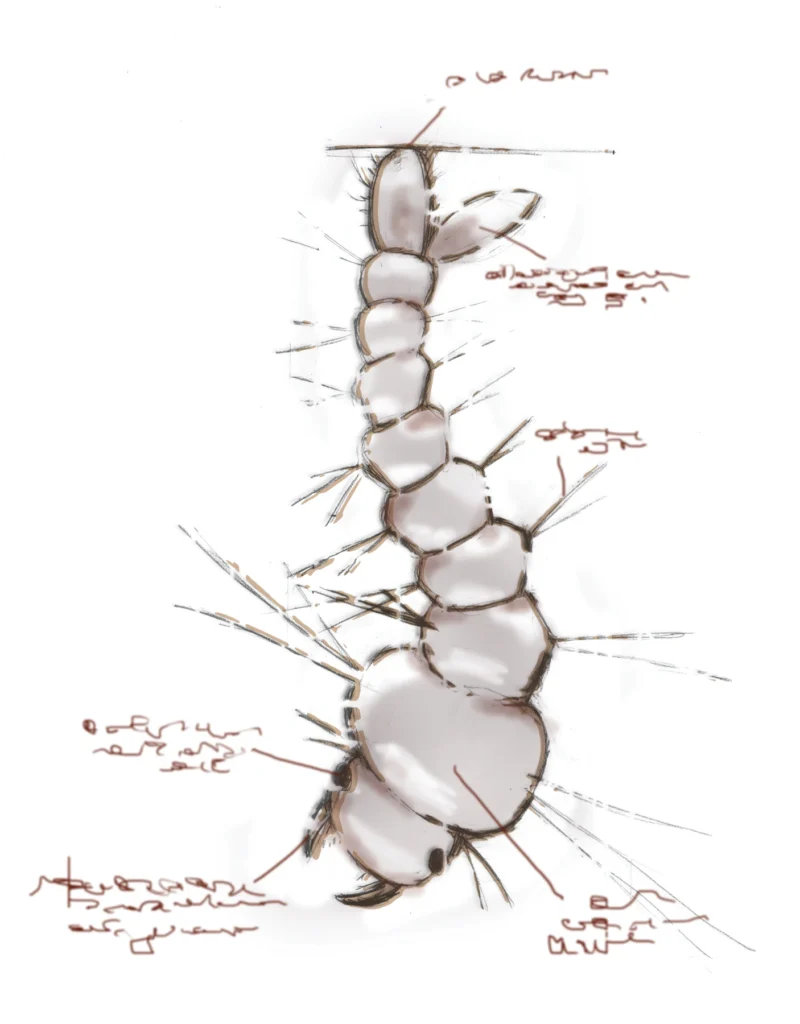

I took you back to the ledge and we stared down at the new lake. It was almost round, a huge, deep bowl in the mountainside like a crater or a caldera. The water was transparent all the way to the bottom, but clouded with a rusty orange haze that blurred the edges of things inside. I imagined it smelling foul, squirming with mosquito larvae.

“Do you see the hole at the bottom?” I said. Catherine nodded. You just stared blankly, like you were daydreaming.

“What is it?” Catherine asked, and no one answered. It was hard to make it out through the deep murk. A ring of ancient concrete wide enough to swallow a house, rusted rebar sprouting all around the rim. And inside it, just blackness. Fathomless depths. A drainhole in the world.

Some of my associations don’t make sense to me anymore. Why one thing should remind me of another, with nothing to link them. The first time you called me from jail, still slurring your words a little, I thought of the hole. And when my wife got sick and the doctor put his hand on my shoulder, I thought of the hole. Just lying there under all that red-orange water, empty and silent and still. Patient.

The three of us stared down at the lake. I looked at you and you looked back, and I sensed that you were feeling the same thing I was. Churning nausea. Nameless dread. Smell of wrinkled skin, bony limbs sprawled in alleyways, red bricks and barbed wire, dark skies over a forgotten world. A feeling that we had slipped off a path and were tumbling, falling.

You swallowed and fidgeted. Your face was pale. Catherine looked at me with some kind of expectation.

“Let’s go,” I said.

I didn’t realize none of us had been breathing until we got back to the trail and I heard three slow gasps. It was minutes before anyone spoke.

“For a billion dollars,” you said quietly as we walked, staring straight ahead, “would you swim in that lake?”

“No,” I said from somewhere deep in my chest. The images began to form at that moment, seeds for future dreams.

“Who do you think built that hole?” you asked.

“Who knows?”

A long pause. When you spoke, still not looking at anyone, there was a small quiver in your voice. “What do you think’s down there?”

“Shut up.”

There was no reason for that response. No rational cause to spit your question out of my head and scrub my imagination. But you nodded.

Catherine looked from me to you. We were quiet all the way to the bikes.

That was the night I told you to take her. Said I didn’t want to do this anymore, that you knew her first and she was your friend’s sister, so if you wanted to make a move, I would step aside and let you. I don’t know why I did it. It wasn’t something I’d been considering before that night; it just came to me all at once in the car after we dropped her off, while the evening air cooled the sweat on my forehead. I remember thinking about those mosquito larvae while I talked to you. No wings or limbs. Just helpless bodies writhing, flailing, silently screaming.

The weight of our deal faded with time. You started dating Catherine and I met other girls and laughed at myself, looking back on a teenage love as light as balloons. But then, of course, you kept dating her, months became years, and you married her. Standing at the altar waiting for her to come down the aisle, you glanced my way and the rightness of it seemed overwhelming. You smiled at me because at that moment it felt like inarguable destiny. Everything turning out for the best.

Later that year you started to drink more. Catherine begged you to stop but you couldn’t. During another scorching summer you got her pregnant. At family barbecues the women crowded around her to share stories and touch her swollen belly while her freckled cheeks radiated joy. The baby was born the next spring and died in its crib for no reason.

I got married, too. It seemed to just happen by itself, like an event in a dream, and the sound of my voice repeating the vows was muffled and foreign. I finished my degree and got a demanding job and rarely ever saw her.

There was a thickness to the air that never seemed to go away. Even in winter, my skin felt gritty, and I sweated in my heavy coats. On the few occasions you and I saw each other, at family reunions, birthdays and funerals, we never talked about the old days or any of our old friends. We didn’t even talk about the weather, which seemed hotter and drier every summer. Everything in our memories seemed to be growing thorns.

And there was something wrong with you and Catherine. The doctor said you shouldn’t try to have any more children, but you did anyway, your genes mixed with hers and curdled, and you made a deformed girl, forever helpless, unable to walk or speak or eat on her own. You drank feverishly then. You began to boil over and hit Catherine, and one night you cracked her jaw and went to prison. You came back years later, broken, everything lost.

I had to remember it then. That conversation on the basement stairs when we were just kids. That tiny little pivot point, a trifling choice that might have changed everything.

The night my wife died I went back to Whistle Lake, drunk and raging and terrified. In the starless dark I hiked the old trail to where we used to sit and smoke Camels, throwing soda cans into the water and

watching them sink. I wandered through the trees all night looking for the rusty lake with the hole in the

bottom, but I never found it. I never found it, Jake. Even when the sun came up and I was sober and got my bearings and searched again, I never found it.

I find it in dreams now. Sometimes I’m flying over it, safe but wary. Other times I’m in the water. The water is sickly warm and I’m swimming, and then I look down and see it gaping around me. Right below me, those infinite shadowy depths, and I feel a current begin to swirl up, an undertow to pull me in, swallow me down. And a deep sound. A rumble chuckling up from that dark, bottomless throat.