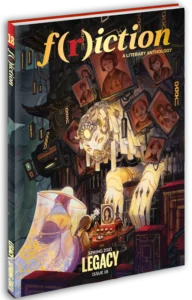

Old Man Miller

Words By Dorian Karahalios, Art By Daniel Reneau

Julie has never had any friends, so when the popular girls in the debate club dare her to sneak into Old Man Miller’s farmhouse, she accepts. The girls persuade Julie to steal the old butcher’s slaughtering knife, or maybe the ashes of his dead wife, or possibly a lock of his hair—cut fresh while he sleeps. And in return, they’ll teach her how to debate boys into driving her out to You-Know-Where Lane to steam up the car windows. And how is Julie to argue? If it works for them, it will work for her: a maiore ad minus. Everyone will finally stop making fun of her mayonnaise-based brown bag lunches. So that night, she waits until her fully-trusting mother is asleep and simply walks out the front door.

Julie does not return.

The debate girls giggle amongst themselves the next day. They pass lip liners, flashcards, and their mothers’ prescription medicines. They spin stories of Julie locked behind bars for trespassing; Julie holding her forehead to the radiator to feign a fever, too embarrassed to show her mayo-eating chicken face; Julie trapped inside Old Man Miller’s, huddled in a puddle of spilled bleach under the sink.

When Julie’s mother reports her missing, the stories stop and the girls say nothing. Such well-liked model students must finish school and go to Ivy League universities. They must become doctors and lawyers and marketing executives and marry rich and powerful men who will give them socially maladjusted children, like their parents before them. Argumentum ad captandum.

Many of them do. And, eventually, they all die—though not because of the war.

One hundred years later, a married couple finds that the world has grown too thick with data, the electronic eyes of a million and a half drones oppressing them as much as the suffocating smog of their ancestors’ metropolii. So they purchase the dilapidated Miller farm in order to recreate the mistakes of their homesteading ancestors and disconnect from society. To live self-sufficiently in a place where the delivery drones cannot venture—at least not roundtrip.

And how hard could it be? Granny and Pop Pop and Weipo and Saba and Yaya and Opa did it, and those idiots nuked the planet.

The wife maintains her job as an archivist. Only a link to the planet’s satellite ring is needed to trawl through the deceased’s social media accounts in order to construct a digital shrine. Meanwhile, the husband renovates their new paradise, learning all he can from public domain DIY GIFs. Together, the couple makes themselves a home considerably larger than their four-hundred square foot asmartment.

Hand in hand, they rip out the mutant weeds, apply anti-radiation fertilizer, and sow the seeds of their independence. They work hard and play hard, much as they believe their ancestors did. The sweat and toil of the day makes way for romantic nutricorn picnic dinners under the stars-and-satellites sky.

They even buy themselves a cow—and they do so without permits or licenses.

Out here, the couple is free to do as they please. Every night, though their bodies are sore and bruised, they let their minds race with possibilities. Their fields of hyper oats will grow strong and they will make oatmeal cookies and oat loafs and oat milk better than the automated factories ever could. Spooned together, the couple cannot help but wiggle their toes against the other’s in excitement.

Perhaps, the wife suggests with a twinkle in her eye, they could even flip the bird to the Department of Reproduction and their damnable certification process. The husband is happy to oblige, repeatedly, and as loud as they both can muster, for there are no neighbors to consider, no awkward shoulder-to-shoulder rides on the commutube the next day.

And for a time, all is as was promised to them by the homestead dark web and its costly, clandestine design courses. Their fields grow, their cow frolics, and their dream takes shape. The couple spends many warm nights relaxing in their hazmat porch swing imagining the wonderful life that awaits them. Their child—no, children!—will grow up without genetic massages and microchip vaccines. No facial recognition database in the world will be able to identify them, and targeted ad bots will short-circuit for lack of data, as if they had divided by zero.

But as the couple works to weave a new life, things begin to fray. The husband is neither a builder nor a media historian, and between the jump cuts and bizarre materials lists, he finds the DIY GIFs mostly uninterpretable. His creative renovations crack and peel, letting in the tainted countryside air, and before long, his repairs need repairs. All the while, the couple’s credit account creeps closer and closer to zero.

And as ion season starts, the polarized winds of change blow for the wife as well. What should be a simple demagnetizing of the clocks by an hour becomes, instead, a series of missed deadlines. Her digital line to the city is muffled beyond recognition by the magnetic storms that blanket the sky. Most days, she sits in silence hoping for understanding from her employer, for mercy. Until a notice of termination manages to find its way through the ion clouds above and shatter all misunderstanding.

Worse still, the frequent storms force the couple inside, allowing the mutant weeds to invade their unkempt fields and choke out their crops. The cow grows a set of three eye-like lumps on its udders.

The covert homesteading courses had not prepared the couple for this. They were taught that anti-rad fertilizer would restore Mother Nature to a place of balance. That in no time at all, they would be milking cows, processing chickens, and turning compost. How could they be failing, being the intelligent, modern sophisticates that they are? The couple’s late-night bedtime chatter turns to stretches of dreaded silence, and there are times when they feel that the inches apart in bed might as well be the space between here and what’s left of the moon.

The husband, needing reassurance from his failures, and the wife, finding herself with an uncomfortable amount of free time, turn to each other for a failproof activity. It is during one of their tantric sessions that the husband happens to pin the wife against a wall in the dining room, causing it to spin away like in a turn-of-the-century Saturday morning cartoon. The couple tumbles, half naked, into a dark hallway that leads into the damp underground.

How fun, they think. Their minds still intentionally set on their previous activity, they wonder what lascivious secrets await them. Finally, a turn in their fortune.

The room at the end is a cold and gray concrete bunker. Stainless steel countertops and rusted metal tool lockers line the walls, and a single metal chair sits in the center of the room, bolted to the floor. The husband is first to find it: a conspicuous painting of proto-pooches playing cards that hides a shelf of rotted film tapes and iridescent optical discs.

The wife squeezes her husband around the waist and cannot contain her mirth. To think that ancient couples in the rural countryside could be so sex positive and progressive! Because surely that is what this is; they tuck their thoughts of crumbling foundations, ruined careers, and overrun fields away.

It doesn’t take long for the couple to track down the correct video equipment. Settling in for a fun night, they set the proper mood with candles, fuzzy pillows, and silken sheets.

We must share this with our friends back home, the wife teases.

The husband agrees, though he no longer thinks of the city as home.

But they must prove they made the right decision. That they are not crazy. They are not undesirables.

They strip naked and press play.

The old video flickers to life and Julie appears.

She is weeping, bound to the metal chair in the hidden bunker. Dirty and soiled, she looks into the camera, pleading, and then to an old man who walks into frame holding a pair of pliers in one hand, a scalpel in the other.

The couple cannot look away. They both realize what they have actually discovered, but like watching the suicide streams of people running through train tunnels or protesting in the streets, they are mesmerized.

Only after the video ends, when Julie, again, has died, faded into the blackness of forgotten history, can time once again move.

The couple sits in absolute silence, their breaths shallow. The wife feels a sharp throb in her belly and doubles over. The husband consoles her, though he is utterly unequipped. There is a weight to what they have just witnessed, heavier than any tumor growing on their cow. In Julie, they see the final reality of their imagined life.

Filled with a nervous energy, the husband traces the peaks and valleys of the wife’s hands. And the wife is thinking the same, exact thing.

The abandonment is subtle at first. With the end of ion season, the couple’s connection to the city is reestablished, but there does not seem much to connect to. Queries take ages and their connection is constantly dropped. Old friends at first do not answer and then later block the couple entirely. Even the homestead dark web has seemingly uprooted itself and moved to a different black corner of cyberspace.

Meanwhile, the couple’s first harvest comes in: a bushel of oats that more closely resembles grubs than grain and then manages to escape in the night. In the paddock, the weeds have assumed dominance over the cow, and the writhing, tangled mass pulsates at night with an eerie, pink glow. Life, it would appear, is a tricky concept, one the couple finds themselves inept at both on the farm and in the bedroom.

Pushing the mutant horrors to the backs of their minds, the couple’s thoughts turn to the city they had left behind. Had it really been that bad? They missed the national anthem karaoke booths, the robot sex parlors, and the processed food products that tasted nothing like the nutricorn rations they’ve been eating for months. The husband jokes that he even misses the museums, though you only ever went there as a punishment for thoughtcrime.

And that is when the wife has the idea. One that will save them and preserve their way of life, all at the same time. They could not go back to the city, but they could bring the city to them. They could start their very own museum, make it a cautionary shrine of a barbaric time featuring Julie and the other victims of the sadistic old man who filmed them. She can do the research, and he can write the grant applications. They kiss—for what feels like the first time in their lives.

The wife finds it easy to use her skills as an archivist for historical research instead, but pulling a narrative thread out of the chaos of pre-war artifacts proves to be more complicated than scrubbing a deceased CEO’s private messages. For the CEO, there is always a friend, an acquaintance, a work colleague. Someone who will vouch for exactly the opposite of what you’re trying to hide.

But Julie had no friends. No mentions in the newspaper, no accolades in community center newsletters, and not even a holiday e-card. Only a mother who claimed her to be a sweet angel—and debate club teammates who vouched for exactly the opposite.

So the wife constructs her first exhibit around—rather than on—Julie, pulling information from local residents, classmates, and debate team newsletters. She treats each corrupted data file of the past, each fragmented digital conversation, and declassified government document as a cowlick to be massaged back into its place of beauty.

From this, she weaves a narrative of a quiet girl, a shy wallflower, who was too insecure in her own self-worth to make much of an impact on the world. A girl who was doomed to have what little of a life she had cut short by a prolific local serial killer.

But the National Endowment for the Truth rejects the initial application. To date, there are already two-hundred-and-forty-seven museums dedicated to serial killers of the past, each more mind-numbing than the last. Thought criminals have literally been dying of boredom. The truth, they write, needs to be spicy. It needs to be as engaging as any daytime holosoap or webplay. And it needs to be open to the public, as per their new, progressive minister’s mandate. Ninety-eight per cent survival rate.

Then perhaps, the wife thinks, Julie’s debate club teammates were on to something. After all, they went on to Ivy League universities and married historically significant men. Combing through old interviews surrounding Julie’s disappearance, the wife finds videos and newspaper quotes from the debate team. Not to speak ill of the dead, they said, but Julie was something of a tyrant.

Maybe, the wife hypothesizes, Julie and the other victims weren’t victims at all. The grant office’s rejection letter creeps into her mind like the weeds strangling their cow. Spice. The likes of which even the Supreme Minister has never seen. The wife feels the flames of her old archivist passion rekindle. The real story is in the space between the data. Teen pregnancies, vandalism, joyrides, political activism—maybe Old Man Miller was just a citizen concerned with the corruption of his society’s youth. So the couple’s museum is to be an exhibit, not of the corruption of the past, but the purification of it.

The grant money begins to trickle in, and Julie rises as the star exhibit.

The museum becomes the wife’s entire world, and the husband is happy to continue writing grants and overseeing professional contractors. Though the two are as happy as when they first arrived in the countryside, there persists, still, an empty space, a dark vacuum, between them. When they embrace, each reaches with their hand to the empty space beside them and paws at the air. They think of the victims in their museum—especially of Julie—and realize what’s missing.

They decide to adopt.

The adoption agencies, though government-run, are at least competent enough to deny the application of a penniless couple living in the boonies. This much the couple understands through the laughing faces on the other end of the holovid—but they are determined.

The husband continues overseeing the renovations, and each morning, the wife practices her tour speeches in the mirror. Did you know, she says, that Julie was a sociopathic force of evil? This was before the government did genetic screening. You can see from these declassified documents that Julie was an undesirable destined for murder and/or rebellion.

Every night, the wife adds more red yarn to her conspiracy web exhibit connecting Julie to slashed tires, graffiti, and mutilated animals. One timeline shows a trend of suicides and teen pregnancies at Julie’s school miraculously stopping the moment she disappeared.

The grant money continues to flow, and the adoption agencies are now sending personalized rejection notes. The politicians are in love with the idea, a snapshot of a barbaric time when individuals were allowed to ruin society (and not the other way around). One official notes that their great-great-grandmother used to be on the debate team with Julie and could they please include that in one of the exhibits?

The birth of the museum consumes the couple, and, as the work nears completion, old friends from the city come out of the woodwork to offer their congratulations. These friends always had faith in the couple.

This museum is going to be the greatest thing since injectable bread, they say. They’re glad to be allowed to talk to the couple again.

On opening day, the line to get in trails past the safety barriers surrounding the pulsating oat-cow-weed enclosure and extends to the parking lot half a mile away. The gift shop is stocked full of holovids of Julie’s final moments, novelty coffee mugs of Julie’s tired, tear-soaked face, and T-shirts printed with the phrase: “I had a screaming good time at Old Man Miller’s!”

Before the couple opens the doors, they hold each other close and take stock of all they have managed to build for themselves outside the corruption of the city. They finally understand their Opas and Pop Pops: the draw of a simple life, pure and honest.

Even the security cameras seem to wink in recognition of their achievements.

The weight of the city, the cold darkness between them, it all melts away in that moment. The husband is happy; the wife is happy. The holovid caller chirps.

It’s the adoption agency.