Noonturn

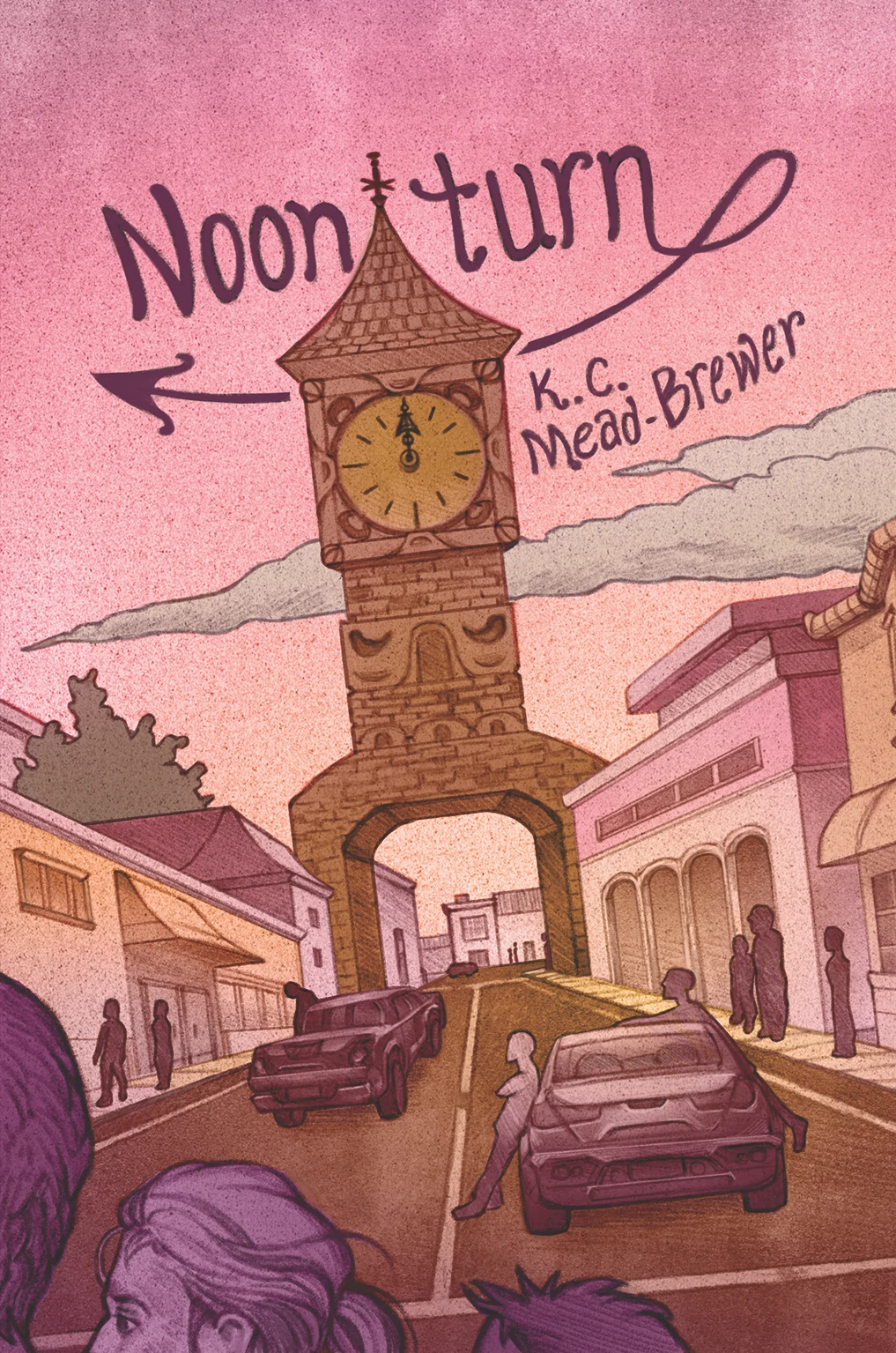

Words By K. C. Mead-Brewer, Art By Michelle Lockamy

The square clocktower stood in the center of town—short, but still the tallest building for fifty miles—and every time it struck noon, everyone who lived there was forcibly turned a full ninety degrees to the left. Not east or west, north or south, but simply to their left.

The town of Psalter, Tennessee didn’t see many visitors, so its residents forgot to think of the clocktower as alien and simply accepted it as yet another odd neighbor. They learned to pull their cars over just before noon— the only way to avoid traffic accidents—and to avoid visiting the restroom around that time, too. Some folks even went to the trouble of making sure they were in a position to see something beautiful when the noonturn overtook them, standing at the ready beside a window, a tree, or some work of art.

The noonturn kept its grip on people for a full minute, holding them fast wherever they were, and while the kids found it squirmy and frustrating, many of the older residents had come to cherish those still moments, finding a queer sort of peace and knowing there was nothing to be done, so why bother fighting it?

The clocktower was older than everyone else in Psalter, older even than the surrounding ash trees, and no one could say exactly when or why it’d been built. Not even its caretaker Ronald Scotch could name who’d actually laid the bricks and first set the whole thing in motion.

It had always been a Scotch who looked after the clock tower, and always, without fail, a male Scotch. Their family simply didn’t have any other children, only single sons; it was the way things were. Ron’s parents had tried getting pregnant again after him, but never with any luck. They even tried adopting, but couldn’t get approved. But when a sister of Ron’s mother passed during her labor, leaving her baby an orphan, the Scotches figured that maybe they’d finally broken whatever seal had been stamped on them. They would take in the little Left Behind as their own, as a daughter instead of a niece. They made plans, painted fresh stars and moons over their old nursery walls—only to end up empty-handed once more. The baby disappeared straight out of its hospital crib.

For a moment, there was an uproar. Missing child flyers were printed on neon-bright pages. Ron’s mother wept open-mouthed and his father shrank inward, unable to make any sound at all.

The doctors couldn’t account for it. They had no explanation. But the more they looked into it, the less they seemed able to remember. The more anyone looked into it, the less they seemed able to remember.

The child’s records and files were all gone, deleted—clerical errors, the doctors said, before scratching their elbows and cocking their heads, asking, Errors about what again? And suddenly neither of Ron’s parents could quite recall either. Standing in the middle of their painted nursery, they wondered at their own handiwork. Wasn’t Ron a bit old for stars and moons?

People in Psalter whispered that the Scotch legacy was haunted somehow by the clock tower, possessed by it, but Ron never let himself believe it. The clocktower might’ve had its oddities, but it wasn’t a god. Of course, he never did have any brothers or sisters, and when his girlfriend Regina had turned thirty a few months back, she’d broken the same news to him that his mother had long ago broken to his father: She was leaving, moving off to some sandy coast. It was just time, she’d said, and she wanted daughters, sons, a great big family. She wanted more than Ron could give her.

It was just time, Ron thought, time, and he knew that no one had ever hated the concept as intensely as himself. Why things should always turn in the same direction, why his family should only ever have sons, why a minute should always last a minute, he couldn’t figure. After all, even if that was the way things were in Psalter, he knew it wasn’t the same for other towns with other clock towers. In other towns where people didn’t have noonturns, where time was said to occasionally speed up—when you’re having fun, when you never want that day or night to end— and then just as often slow down—when you’re bored, when you’re staring at the clock, at a pot of yet-boiling water, at a loved one in the hospital.

In fact, there was only one instance Ron could think of where, just for a moment, a minute had seemed longer than itself, a too-long minute with Regina.

It was the morning he’d finally talked her into it, into trying something new, into trying something a little you know, into timing their sex to coincide exactly with the noonturn. Just to see what happens, he’d said, grinning. Just to see what it’s like.

They’d had to position themselves carefully so that, when the turn overtook them, they ended up face-to-face. She would be his tree, his work of art, his something-beautiful that the noonturn would hold him steady for. And there, for one weightless, absurd moment, Ron had felt himself twist atop her to his left and she twist beneath him to hers, their bodies held together like gears, Regina holding so still she was even holding her breath, holding, holding, holding— Ron had never felt so close to anyone in his life, holding, holding, holding, they’d gazed into each other’s eyes, she up into Ron’s brown ones and he down into her green ones, except he realize-remembered then that they weren’t exactly green, yellow actually, and actually he’d never seen their green before, being red-green colorblind as he was (yet another thing he’d inherited); yellow like the red clock tower’s yellow bricks; and the longer he stared into her yellow eyes the more keenly he felt a creeping sort of panic worm up inside of himself. Shit, he thought, furious and embarrassed as the panic had him deflating inside of her, and though he tried to think of something, anything else—her breasts, her wetness, her smile—all he could see was yellow and yellow and yellow that would never be green, a yellow he’d never signed on for, never agreed to, a yellow that, oh God, was slowly filling up with tears, and what did his own face look like then, horrified, awkward, uncomfortable, upset? The tears welled and welled until her eyes blurred, until they looked like twin balls of lemon Jell-O jiggling—until the noon-minute passed and the tears finally spilled and she turned her face away to press into the pillow, certain what they’d done was a sin. Certain they’d given themselves over to something ungodly. Something unseemly.

Pulling out, soft and ashamed, Ron tried telling her that she couldn’t even imagine unseemly, but she hadn’t stuck around long enough to listen, rushing up to get dressed, get back to work, pretend the entire unseemly thing had never happened.

Unseemly, he would’ve told her, wasn’t what they’d done, but what he’d done. Unseemly was a man who couldn’t hold out. Unseemly was a man who couldn’t put the truth into words. Unseemly was a man who deceived—a man like his father, who hadn’t told his Texan fiancée about the noonturns until they’d already married, until she was already pregnant, a woman for whom abortions weren’t an option, a woman who would never have another child for as long as she lived thanks to that clock tower’s curse. Unseemly was a man who couldn’t control himself, his body, his mind.

Unseemly was what Ron had caught Rudy Blume doing out on the last full moon.

Ron had taken Rudy’s call, listened as the old man sloshed and slurred his way through the words, claiming the clocktower was making an unholy grab for his soul, that the red of its brick was getting redder and redder. Ron figured it was just Rudy’s booze getting the better of him again. But when he went to check on things, armed with a flashlight and his dog Baboon, Ron was shocked to find a zombie-eyed Rudy weeping as he pissed and rubbed himself all over the clock tower’s eastern wall.

Can’t you feel it? Rudy said, tanked out of his mind. Can’t you feel it, Ronny? The belfry— Its bricks—Their red is redder at night. Their red is redder—

Barking her ever-loving head off, Baboon scared the old drunk away before Ron could reach him. Even for Rudy, it was a new low.

Shining his light over the wall, Ron felt gooseflesh flare across his arms. The slick, wet way the bricks gleamed, he thought they looked more like dragon scales. He thought maybe their red did look redder than it had before, but then, of course, he couldn’t see the color red. If the bricks indeed looked redder, to him they looked yellower, muddier, like grime off rotten teeth.

Sometimes Ron wondered if he wasn’t seeing the clocktower colorblind, but simply for what it truly was. Sometimes he wondered if he might be the only one who could.

Joe, Ron’s father, had died three months previous falling from the top of the clock tower. He’d broken his back and both of his legs, but hadn’t died right away. He’d died slowly in the county hospital, suffering from one cognitive disorder or another, something because of how he’d hit his head.

Their conversations went like this: Ron asks Joe how he’s feeling; Joe tells Ron, them, them, them, their happy arms, that preacher, you know, that red Sunday preacher, say howdy my boy, them, them. Ron asks Joe what he wants to look at during the noonturn; Joe tells Ron, lunch noon, it’s time dancing, we’ll dance with them, dance them red, red, red. Ron asks Joe about the missing child flyers he found stacked in the hall closet; Joe tells Ron, them, them, dancing red, my boy, Ronny my boy, boy-them, boy-them, that’s what they say. Ron tells Joe he misses him, please come back, I love you, Dad, you were always my best friend, even when you weren’t; Joe tells Ron, the sun is happy, that’s what they say, the skirt, the sun, the red, red, red, she’s calling, my boy, them, them, my happy yellow sun. The doctor said it was tragically normal for people in Joe’s condition to struggle for the right words, to not even realize that they’d used

entirely irrelevant or made-up words, instead. It can be very scary for them, she explained. It’s an unsettling thing to realize you can’t make yourself understood.

Ron shook his head. The tears made him look so young. The way his broad shoulders slumped. The way he held his Chattanooga Lookouts cap tight against his heart. But the doctor didn’t live in Psalter, so he knew she wouldn’t understand. It wasn’t any damage or disease that’d made his father spout words that didn’t fit or exist. It was the clock tower. It’d knocked his brain in a permanent left turn.

People whispered about how exactly Joe had managed such a fall. About his relationship with all those lovely bottles, just like his father and his father’s father. About how clock towers weren’t the only problems running through the Scotch family line. People said it was a crying shame, no matter the how’s and why’s, and of course it wasn’t their place to judge, but could anyone remember the last time Joe had been to church? People baked brownies and casseroles and wrapped them in tinfoil and brought them by Joe’s-now-Ron’s house. The house Ron’s father had left him, full of leaks and holes and creaking boards. Just dropping by, just checking in, just extending our condolences, and by the way, did you know the lawn around the belfry was sprouting up with dandelions? Did you know the clock tower’s weathervane got itself bent in the last storm? People said Ron wasn’t the same after his father’s death. Said he wasn’t keeping the clocktower as clean and orderly as Joe had. Said he was slower to call the brick mason for repairs or to chase away teenagers with their spray-paint. Said they caught him crying in his driver’s seat. Said his lights were on at all hours, his entire house falling apart, blazing yellow against the night.

Ron wasn’t the only one who felt differently about the tower since Joe’s fall. Suddenly the kids in town were struggling even harder against the noonturns, as if in some kind of revolt against the belfry and all it’d saddled them with. None of them ever managed to break the hold, of course, all inevitably turning left as that big hand found its way unerringly back to twelve. Even when Louie Edson, the football coach’s boy, tried shackling himself in place, mounting metal cuffs tight to his basement wall, it was no use; all he ended up with come noon was a broken leg, a broken arm, and two hairline fractures to his collarbone. It cost Louie his place on the team that season, and his father was so steamed, he couldn’t even look at him for three weeks straight, never mind sign his casts.

Not long after the Louie incident, the clock’s chiming started growing louder, more constant, as if it feared it wasn’t being understood. Ron understood it perfectly, saw its dark yellow bricks exactly as they were—but he turned away. The clocktower could bellow to eternity for all he cared. Just because Ron could hear it, didn’t mean he ever planned on listening again. Because what could be worse than all that had already happened? There was no one left for the clocktower to steal from him. The Edson boy’s bones would heal; he’d play football again. What more could the clocktower possibly do?

Birds began avoiding the tower, refusing to land on its witch-hat roof. Some wondered if it wasn’t because Joe’s ghost was roaming around up there, ever the caretaker, chasing them away. And then, before you knew it, for a solid mile around the tower, all cell phones—no matter your provider—suddenly lost their bars, all cameras lost their focus, and all GPS lost its signal.

It was then that people started leaving offerings for the tower, perhaps hoping to appease or quiet it. Perhaps just hoping to keep things from getting any worse. They laid out all manner of things: cantaloupes and watermelons, bouquets of fresh flowers, antiques and heirlooms. The schoolmarm Sarah Skye even gave up her own faded wedding gown, the one that’d once been her mother’s and grandmother’s, clasping her wrinkled hands together over its yellowing lace as in prayer.

Some residents started debating the merits of leaving Psalter altogether—as was normal from time to time—but they knew that this too was pointless. The clock tower’s effects followed them wherever they went. Ron knew it still had his mother in its grip, wherever she was, just as it still had Regina. And though Ron wouldn’t admit it, he often wondered if even his father wasn’t helplessly turning over in his coffin each noon, the tower rolling his tuxedoed body left and left and left like a rest-stop hotdog.

Not one week later, the history teacher Howie Rays went streaking around the tower, shouting nonsense—The books are all the same! or Rutabaga, rutabaga, rutabaga! or Napoleon’s white fucking horse!—and then shot himself for all to see.

People had plenty to say about this, and never mind what Howie’s widow Gloria tried telling them, tried explaining. It was probably schizophrenia, they all said. (Hadn’t his father had it? Or was that his aunt?) Or maybe it was a psychotic break. That can happen sometimes, especially if you’ve already got something rolling around loose upstairs. (Hadn’t he and Gloria been seeing a therapist together?) Something like anxiety maybe, or depression. That was probably it, they said, they all agreed. His mother had definitely been depressed. Runs in the family, they said. Runs in the blood.

What was Howie to you? Ron wanted to yell at the clock tower. What was Gloria? What did anyone matter, anyone who wasn’t a Scotch, who didn’t have the ability to give the tower what it needed? It made him feel like a child, this desire to scream and scream and scream.

Ron had to borrow one of the firefighters’ hoses to get all the splatter off. Watching the blood rinse down into the dirt, yellow blood into yellow dirt, he wondered if Howie had realized that he, a natural right-hander, had shot himself in the left temple.

It turned into something of a controversy that Ron had cleared up Howie’s remains. Some folks thought the clocktower ought to have been left its blood—Howie’s final offering, they said. His final sacrifice. But it hadn’t sat right with Ron or Gloria that his remains be left out dripping like that, exposed.

He was a human being! Gloria shouted. He was Howie! She hurled the words at them, but the belfry’s erratic chiming drowned her out. Only the tower heard her clearly.

Ron felt for her. Because maybe it was his fault that her husband was dead, if he’d just given the clocktower what it’d wanted. Because he’d since learned that his father had likely jumped instead of fallen. Because now he and Gloria both knew what it was like to be abandoned by the ones they loved.

It turns out Joe would’ve died soon anyway, the doctor had told Ron, uncertain if this was good news or bad. Apparently he was seeing a specialist over in Baltimore. Prostate cancer, she said. Stage four. His body was riddled with it. You’ll want to make an appointment for yourself while you’re here, get checked out. It can be hereditary, you know.

Why didn’t he tell me? Ron asked. The question broke out of him letter by letter.

The doctor frowned. Maybe he didn’t want to, she said. Or maybe he didn’t know how.

Even after Howie’s death, most weren’t actively afraid of the clocktower until it began running slow.

What the hell are you thinking? they all demanded of Ron, knowing instinctively that something was very, very wrong. This is your job! Your one job! Now do it!

But what they didn’t know was that Ron was doing his job. The job his father hadn’t been able to do. What they didn’t know was, though the clocktower needed Ron, he never needed the clocktower in return. What they didn’t know was that Ron wanted the clock to run down. If he was going to keep being left behind, if he was going to die alone, then he figured it might as well happen for a reason. And if the clocktower wanted to go out screaming, chiming its bell off, why not let it? After all, it wasn’t as if he could simply go up and get winding. Because there was something else, something very basic, his neighbors didn’t know.

The clock doesn’t need winding, Joe had told him, back when Ron was still waist-high and freckled.

It doesn’t? Then how does it run?

Even as young as he was then, Ron knew clocks needed winding and that a clock the belfry’s size would need weekly attention. Since before Ron could remember, he’d been fascinated by clocks, their pull on his family, the way they ticked, their gears and pulleys all working together with such a simple elegance. Like watching a beautiful woman walk by.

Come on, his father said, smiling a sad smile. I’ll show you.

It was the first time Joe had ever let his son inside the belfry. A narrow, shadowy place with air that tucked in around them like breath, as if they’d climbed into the breast pocket of some massive, stony giant. Wooden ladders zig- zagged the prism’s interior and dust fell into Ron’s eyes as he climbed up and up and up.

It was dark at the top platform, dark everywhere. Joe reached for the flashlight in his back pocket. Ron wanted to cling to the man’s arm, but forced his hands to keep tight to his sides. He wasn’t a baby anymore.

Aren’t there any lights in here? Ron asked. He’d studied pictures and blueprints of other clock towers. He knew what was normal and what wasn’t. Like lights. Like the ropes and the hand-crank for winding, the massive hanging weights that would need adding in wintertime and subtracting in summer.

His father grinned. Lights? he said, chuckling, resting a large hand on his son’s thin shoulder. Ronny, you ever wonder if your food asks the same thing about you?

He clicked on his flashlight.

Ron’s hands fell limp at his sides. Dad… what is it?

It’s the clock tower, he said. That’s all it is, Ron. That’s everything.

Everything, Ron said, gaping. What does it want?

Want? You can’t listen to folks around town, Ron. The clocktower doesn’t want anything. Not trouble or pain or even you or me. It’s a creature of needs. And it doesn’t need winding.

A creature… Ron whispered. Then what does it… need?

Feeding, Joe said. Complacency. He spat the word. Something only we can give it. Joe gave his son’s shoulder another tight squeeze. I’m sorry, he said. He was so quiet, Ron almost couldn’t hear him. I’m so sorry.

But even as a boy, on some level, Ron knew. Ron understood. You don’t have to be sorry, Dad. It isn’t your fault.

Joe stared ahead vacantly. This didn’t have to be your lot, Ron. I never needed to have children, did I? It’s not as if I ever needed—He wavered, his voice, his legs, his arms, losing his grip. Could’ve stopped myself, he whispered. Could’ve just dusted off alone. Could’ve just taken all this mess to the ground with me. Could’ve looked harder for a way to stop it. Could’ve bothered to look at all. He laughed then, a sound so sharp it made Ron wince. Because she went missing, didn’t she? All those fucking flyers. Even after everything, even after doing everything it wanted… Should’ve looked. Why didn’t anyone look? Your aunt died and then—your mother was crying… I can’t remember. I can’t remember.

Ron stared up at him, confused and wide- eyed, his chest, his throat going tight. His hand stretched out, slowly, slowly, and clasped his father’s. And though it took a long time—at least, a long time for a boy holding his breath— he eventually felt his father’s fingers come alive around his, gripping them gently, large over small.

It’s true, Joe said, stronger this time. You weren’t needed, Ronny. I never needed you. But holy God, boy, were you wanted.

Gloria’s face was red from crying and her eyes looked massive and bleak. She was still in her funeral black, hadn’t managed to take any of it off all day. The kids were over with their grandparents. She hadn’t seen her girls since the ceremony that morning; she couldn’t face the Howie in them. All the things she’d never bargained for.

Make love with me, she said to Ron, sniffling, worrying a blackened tissue. Make love with me. In the clock tower. Please…Her chin trembled. The tower needs this. I need this—I need it all to stop.

Ron thought about how his mother had left him to find whatever it was she’d needed. About how climbing up the clocktower felt like climbing down a throat. About how the red had gotten redder. About how he was still his father’s boy. About how Regina had never once confided in him about needing anything.

Gloria had always just been Gloria to him before. The CPA. The Sunday School teacher.

Yet he realized then that he was jealous of Dead Howie with the lovely, loving wife. He was jealous of Dead Howie with the pretty pair of little girls and the way they’d all looked together on Halloween, a king escorting his princesses. Ron shook his head.

You miss Howie, he said. That’s all. You’d regret it later.

I won’t, she said. Take me up there—please. Can’t you see what it’s doing? The noonturns are lasting longer, the chimes are everywhere all the time—

It’s starving, Ron thought.

It’s angry, Gloria said. It’s angry with us. It wants us. It wants love, not all those ridiculous tithes. Please, she said, and kissed him flat on the mouth before he could stop her.

There was no feeling in it. She really did miss Howie. Most women in Psalter knew better than to ever get involved with a Scotch, knowing their history. Their ghosts. She only needed him now because he was the way in, just another of the belfry’s cogs. Ron had known it, but it still hurt to feel it pressed on his body that way. To know for certain he would always, always be alone.

Ron stepped back, out of her grip, out of kissing reach. He narrowed his eyes at her. Dead Howie’s pretty wife. The woman he’d made a widow. The kind of woman who wasn’t afraid to shout to make herself heard. Ron thought of her daughters without a father, princesses without their king. He thought of the way his own parents had once smiled and laughed together, painting over his old nursery walls with moons and stars for…someone. Hadn’t it been for someone?

What if they really could be mine? he wondered. Would the clocktower let me keep them? Howie’s little Left Behinds. Something other than all this forever-lonely. After all, sometimes things did change. (Didn’t they?) Things could skip a generation. Things could be different, just for once—

No, he said. He didn’t recognize his own voice. No, I’m sorry, Gloria. No.

Because he could be stronger than his father. Because he could say no to those things he merely wanted. Because wanting wasn’t enough. It couldn’t be.

It was the first call he’d gotten from Regina since her move some five months ago. The first call he’d gotten since the clocktower had finally given up its incessant chiming, had begun running smoothly and timely once more, its alarmed citrine blush settling back to its old relaxed hue. Something had happened to reassure the belfry, to comfort it after Joe’s death and Ron’s decision. Something Ron couldn’t place. Then, crying with those yellow eyes, Regina told him:

It’s a boy, Ron. I didn’t want to tell you before. I didn’t want to believe it. But it’s a boy. I’m pregnant and it’s a boy.

The words were right there inside of him:

Whatever you need to do, I’ll support you. I’ll go to the clinic with you, hold your hand. Put it up for adoption. Give it any name you like, so long as it isn’t mine. I’ll send you money. I’ll work for you my entire life. Just stay away. Just don’t come here. Just don’t let him be like me. The words were clear and neat in his head, but he couldn’t get them out. They crumpled like train cars against the back of his teeth. Because why did he deserve to be alone? Because why did it have to be his responsibility to change things? Because, after all, even if she could never love him, never forgive him, perhaps a baby could. Perhaps this baby, his son, might be stronger than him. Perhaps his son would finally figure out how to stop time.

White noise and more crying. She couldn’t give it up. She was her parents’ daughter and she couldn’t give it up, no matter how badly she might want to. She was coming back. A baby needs its father, she said.

Ron turned, a window at his left. The clocktower chimed a crisp, eternal noon.

Gripping the phone tight, letting the world work on him, Ron wondered if he’d ever learn to find the peace in these still moments, knowing the turn was already in motion, knowing there was nothing to be done, so why bother fighting it.