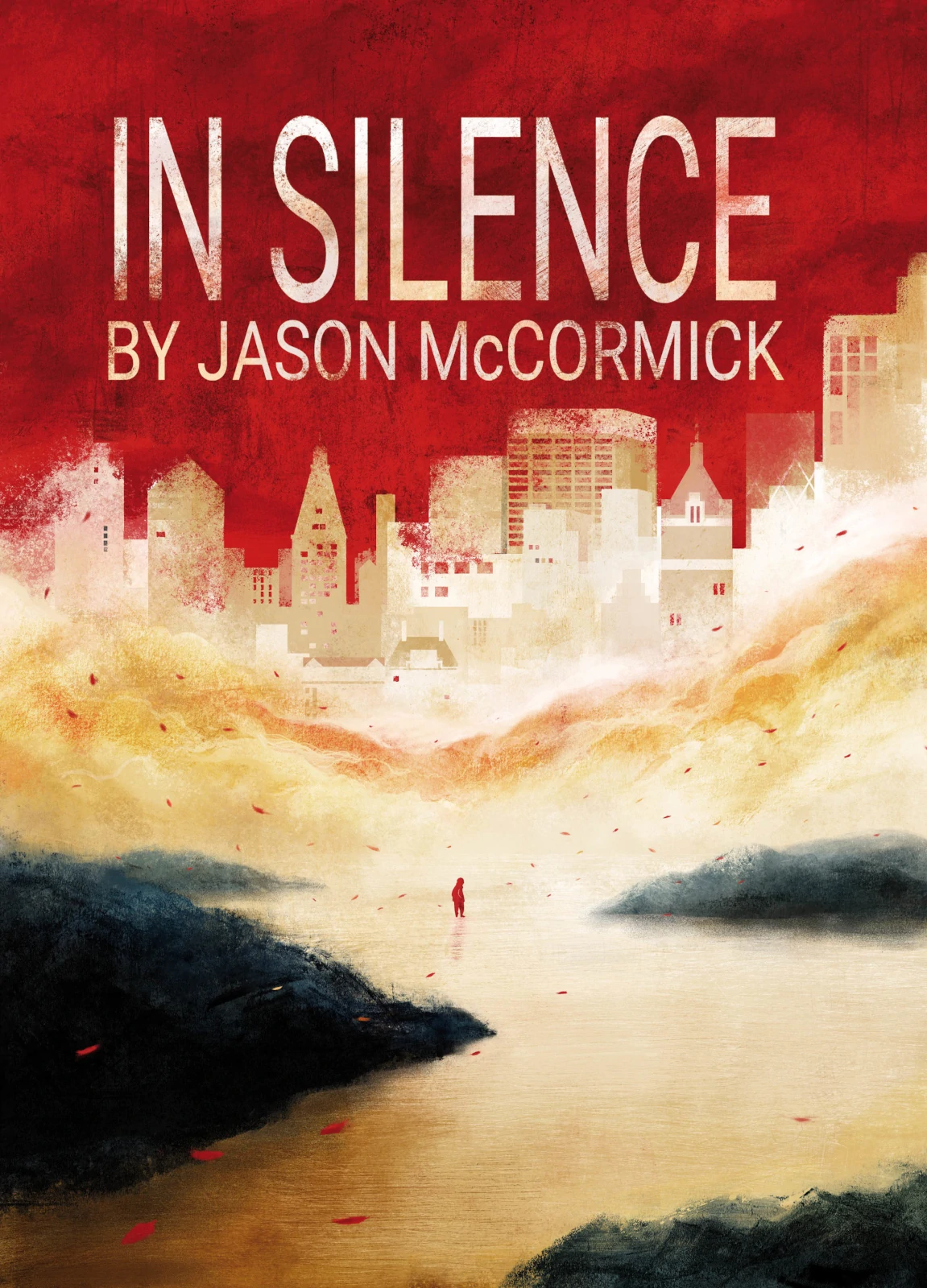

In Silence

Words By Jason McCormick, Art By Carly A-F

Even after all the time she had spent cleaning, she still found herself listening for some sort of noise—water in the pipes, perhaps, or the hum of fluorescent lights. Outer offices often had large windows and sometimes, when she was working on the top floors of buildings, the wind would gather strength and batter against the glass. Sometimes, the view from those high windows distorted the streets below so that New York looked a bit like it used to and distracted her from the worst of her memories. But the interior offices were always dark and silent. There was no power in these buildings to turn the lights on and no water to run through the radiator pipes anymore. It didn’t matter. Everything had to be cleaned.

To stop her ears ringing in the silence, she kept scraping the coarse sponge across the eggshell wall, tearing away another stain.

She had only recently started on this building, just off Fifty-Sixth and Fifth Avenue. She preferred office buildings over residential units. Seeing how people had worked was never as hard as seeing how they had lived.

But today, the silence felt heavier than usual. Sometimes that happened. She thought of humming, but her throat resisted vibration. She hadn’t spoken in so long. Her mother once told her that nice girls were quiet. Being quiet had helped her stay alive. But she didn’t think of herself as “nice” anymore.

She had always been a good listener—even now, with nothing to hear. That had been useful, too, during the worst of it. She stared at the brown stain, fixating on a wad of hair that hadn’t come loose yet. She let her arms hang by her sides, just for a moment.

Then she heard the thump.

A flare of adrenaline coursed through her. Rats didn’t make sounds like that. And it couldn’t be the Ruined. No, they were gone, all gone. She was sure of it. And even if she had somehow missed one, the Ruined thrashed about—they didn’t softly thump.

There was silence again. But something had made that noise.

She dropped her sponge and felt behind for her crowbar. It can’t be them, she thought over and over. They’re gone. She felt her breath catching at the top of her lungs. She tried to calm herself. It’s not them. It really can’t be them.

She still had nightmares about the Ruined. Tom had said that some dreams—déjà vu dreams—were the brain trying to make sense of what was going on in the present by scrambling up everything that had happened in the past. He had said we do it when we’re awake, too—we understand now by remembering back then. That was why the crowbar was always within her reach. She knew how to swing it like a war hammer or jab it like a spear—these months had reshaped her brain and her throat and the shape of her hand to fit perfectly around this crowbar, all callouses on metal.

It took her twenty minutes, but she found what had made the thump in a room near the back of the building. She had ignored a small closet there when she first came in. But now, the door was half-open and a body lay crumpled on the floor. She took a few steps closer. It was a thin man in a tailored suit. Standing over him, she saw the dried vomit crusted around his mouth and staining his shirt. He must have taken pills. When he had died, violently and alone, hiding in the closet, there probably wasn’t enough room for him to fall over completely. So there he’d stayed, leaning against the door until eventually the weight of him had broken the lock.

Now, he was just something else to clean up.

As she dragged the body down the stairs behind her, she tried to pretend the rhythmic thunking was anything other than what it was. She was upset about the interruption to her day, but she tried not to blame him. There had been so many suicides, especially at the beginning. So many saw their world falling apart and felt helpless. Back then, people were only just beginning to understand how the sickness worked. They knew that if you got hurt by one of the Ruined, you would become one of them. But if you died before they hurt you, you wouldn’t change.

She didn’t want to start thinking about it all again—not about the Ruined or about Tom. She knew that once she started, it would be impossible to hold back. “You tell yourself not to think about pink elephants,” Tom would say, “pink elephants are all you’ll get.”

Tom used to say things like that. It had been charming and annoying.

He was different from the other people who had survived for so long. He wasn’t a prepper or anything—he just knew the city. He had been a UPS driver. Or FedEx. One of them. Of course, she had never seen him in his uniform. He wore leather constantly, even when the New York summers got to the kind of hot only the city was capable of. He claimed the leather had saved his life more than once, like armor. When she decided that she was going to be like him, they found that women’s leather jackets were consistently terrible. There was less pocket room and the material was always thinner. Eventually they found some small men’s jackets that did the trick. She hid them in all of their outposts.

She never had just one jacket. It was bad to get attached to things. The one exception was her crowbar, which she’d had almost since the beginning. She had taken it from a young man. She never knew his name, but he was already dying and wouldn’t be needing it anymore. He had wanted her to kill him with it, but she wasn’t there yet. She didn’t kill anything in the first few weeks. Instead, she stayed with the largest groups she could find, hiding in the crowds. Before Tom, the secret to surviving was to know how to disappear and to keep moving. She had started with a group gathered in a high-rise near Central Park, then a barricaded block in the Village. It didn’t take her very long, maybe a few weeks, to stop asking people their names. No one ever asked her.

Tom appeared when the barricades had failed and the group was walking toward Tribeca because someone had heard there were survivors camped out in a post office down there. Tom seemed impossibly old compared to everyone else, even though he claimed to only be fifty-four. His hair was on the saltier side of salt-and-pepper, especially his beard. All the men had beards now. Shaving had become both a luxury of time and a risk due to the smell of blood.

By then, people had started to realize that the Ruined were blind, but no one was sure yet if they hunted by sound or smell or both. Tom’s beard made him look like an actor from a TV show she had seen once, but she couldn’t ever place it. Still, there he was. And then, as soon as they met, he asked her for her name and tried to shake her hand. It had seemed so strange and old-fashioned.

She tried to shake off the memory. Sometimes, when she remembered his smiles and the way they took care of each other, the hurt was so distant that it barely registered—like trying to move fingers that had gone numb. But most of the time, when she remembered him, she felt the same as she did that day outside the museum when she realized what she had done. She felt like shattered porcelain that had been poorly glued back together—fragile and with pieces missing. She never knew which way her mind would go, so she just focused on her next task. Right now, she needed to move this body down the stairs.

When she got it to the ground floor, she lowered the makeshift metal ramp at the back of her UTV and dragged the body onto the flatbed. It was about the size of a golf cart, but sturdier—it bore the logo of the city’s Parks Service and had been used by the groundskeepers in Central Park. It was almost fun to drive, when it wasn’t weighed down. She scanned ahead and identified two other mostly whole bodies that she could load into the back before heading to the park. She had to clear the streets too, of course. No one would care if the buildings were clean if they had to step over corpses to get inside.

When she first started clearing the roads, she had tried using one of the city’s snowplows. It had taken her hours to get the hang of driving it and the blade was damaged, so it created a mess as she pushed through the streets. There were just so many laying around everywhere and she needed to clear a path to the park. But the brutality of the truck bothered her.

Now there was a pathway, and it gave her enough space to get the cart through. The smaller vehicle could only carry a few at a time, so the process was slow but more meticulous. She made sure to siphon unleaded from the city’s cars and stored canisters all over. She couldn’t afford to ever run out or spend her day walking blocks to refuel.

Once everything was cleaned, she would collect all the gas canisters again. It was dangerous to leave them around and she would need whatever was left when the work was done.

Early on, she realized that it would be impossible for her to bury everyone on the island, but their bodies had to go somewhere. She had contemplated using buildings and making them into a series of mausoleums. But neither she nor the bodies would have been able to handle all those stairs. So instead, they had to be stacked.

She made the first pile on the Great Lawn at the center of Central Park. At the time, it had seemed far enough away from the Met, but it was getting more difficult to maintain a perimeter that felt respectful.

Driving from the south end, she could see the tips of other hills she had made. The stench was strong, so she pulled the face mask she kept tied around her neck over her face and mouth.

When the sickness hit, the authorities put the quarantine into action almost immediately. She remembered people running everywhere and explosions all around Manhattan. Every bridge and tunnel was leveled within a matter of hours, and the narrow places in the rivers were bombed-out, pulling the banks further apart. Gunships floated back and forth, looking for anyone desperate enough to try crossing anyway. There was no way off the island.

She was near one of the subway stations in SoHo when she heard a sudden crash of water underground. Hundreds of rats came running out just ahead of the flood, which rose up the subway stairs, stopping just a few feet shy of the street.

People rioted and looted, early on. They went after essential products first—food, drinkable water, toilet paper. But then some started smashing storefronts and lighting fires in the street. They were angry that they had been abandoned. All she felt back then was despair. That was before things got really bad.

But then word started to spread about what happened at the museum. While others were raging, a group of people had gathered at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Some said they were the teachers and academics of the city. Others claimed they were the artists. Whoever they were, they had decided that the museum was worth protecting. The stories said that they held back the looters until eventually a group too large to be fought off came to the museum doors, determined to burn the art and the history down. The people inside knew they could not hold so many people back, so instead, they invited them in. They convinced the mob to protect the art. After that, everyone knew the Met was off-limits. Even when attention turned to fighting off the Ruined, the stories continued circulating—there was an army inside the museum, and it was the last good place in the city.

Back then, she needed that story. Every other piece of news was horrible, especially when people started to figure out the truth behind the sickness. Rumors of a cure or vaccine circulated. But there were no army scientists brewing a cure in a Brooklyn basement, determined to save them.

Looking back now, she knew that the anger over the quarantine distracted people from actually doing something about the sickness. Once it took root in the city’s population, the infection spread fast. All it took was a scratch or a bite. Sometimes, if the wound wasn’t bad, the process was slow, but no one recovered. Eventually, the sickness would take control and eat away at them, turning them into the Ruined. There was no cure and there was no running away. For the uninfected, all there was left to do was survive, no matter what it took.

People began to call them the “Ruined” when they understood that they had to be killed. They didn’t die like normal things. Their brains had to be destroyed. Gunshots could do enough damage, but the noise always drew more of the Ruined. So, while killing them up close meant risking infection, at least it could be done quietly. Some people kept count of how many they had killed. She didn’t. Any number felt both like too many and far too little.

And now, it was just her and the rats. The rats never got infected, never died. Like the Ruined, all they did was consume. And like the Ruined, they never went into the water. That’s why the quarantine worked the way it did. Someone knew that was how to keep it contained. And the city was left to fend for itself. She didn’t kill many of the Ruined, but she did kill the last of them. On Tom’s final day, they found a few in Kips Bay. They tried to be smart and slow, but Tom got scratched. It was small, but they knew what was going to happen.

He didn’t want to talk about it. He said that he wanted to see if the stories about the Met were true. It took them almost two hours to walk there because he needed to take breaks. Now, all she could remember about that walk was staring at his right hand, trying to memorize the curve of his knuckles. When they arrived at the museum, they pushed open the doors and wandered around for hours.

It was a while before she noticed Tom was chuckling.

“What?” she asked.

“After everything we heard, there’s only fourteen bodies.”

“So?”

“Fourteen,” he repeated. He scratched his beard and she watched as hair flaked away in patches, falling onto his shirt. “I thought it was an army. I really believed it. And nothing’s missing.” She hadn’t noticed. “Fourteen people. It’s like a goddamn epic poem.”

He died sometime that night.

He insisted on sleeping in the Modern Art exhibit and that she sleep somewhere else. In another wing of the museum, there was an entire pyramid, picked up block by block in Egypt and brought to New York. The Temple of Dendur was reconstructed on marble floors and surrounded on all sides by a water feature, and the whole thing was housed in a section of the museum made entirely of glass panels. She slept on one of the steps of the pyramid, looking up at the stars in the sky and smelling the stagnant water. It was the smartest place she could sleep. There were only a few points of entry and everything echoed off the marble.

Tom wouldn’t have been able to sneak up on her.

Looking back, she hated that she had thought that. It meant that she knew what was going to happen to him. And yet, she knew that if she had allowed herself to realize it completely, she would have chosen to be close to him and take the risk. She would have made more of a fuss and insisted that he hold her one more time. They had never been lovers, but she had loved him. They were the last two people in Manhattan.

She came to the park every day now, for work. Some days, she could get the cart loaded up several times. Today, she knew she would only be able to manage the one trip. The pile she was currently building was getting too tall to climb, so she laid the new bodies next to it. She couldn’t imagine how many there were now, and how many more there would be by the time she had finished it all. Would the park be large enough? Would she have enough gas when the last day came? She didn’t want to think about it. “Pink elephants,” she thought.

By the time the last body was off the cart, panic had really set in. What if she was doing this wrong? No one had asked her to clean up the city.

She was sure he had changed when she went looking for him that next morning in the Met. She found Picasso’s “Head of a Woman” toppled over. Tom would never have done that. He hadn’t gone far—just to an exhibition of old European furniture. He was leaning against a partition, slouched and drooling. The Ruined were always so quick, ready to attack. But Tom looked tired. She wanted to say she was sorry before she did it, but she knew she couldn’t risk warning him. And it wasn’t Tom anymore.

After it was done, she apologized over and over. She left the museum and was several blocks into the Upper East Side before she realized that she had dropped her crowbar next to him. She couldn’t protect herself without it. The day before, they had been so sure that they had found all the Ruined. But the city was so big and to be alone was too vast a concept, so she needed her crowbar. She turned back toward the museum, toward Tom, but was shaking so hard that she had to steady herself against a powerless electrical box. It felt like parts of her own body were on the outside, exposed and convulsing. She stumbled back toward the museum, toward her crowbar and toward Tom and then she fell, her palms grinding against the sidewalk. She looked toward the top of the fancy apartment buildings through tear-blurred eyes and held her breath for as long as she could.

And then, she screamed.

She did not know she was capable of such noise. Silence was hers. Silence had protected her from the people who might have pushed her away. Silence had kept her from the Ruined. And when she had someone to talk to, when she had walked behind Tom on the way here, silence protected her then, too.

Her voice only echoed for a moment and then it was gone. So, she screamed again.

For the first time in so long, she wanted to be found and she didn’t care what found her. But there was no reply.

So, she kept going. She walked for days, not thinking, just moving. When she remembered Tom and his kind hands and his stupid words and the smell of his jacket and him underneath it, she would scream again. She was in the Meatpacking District, staring out over the Hudson, when she let out the last scream. Her voice was broken and her throat raw. When the last of her voice gave out, she knew for sure, she was alone.

She went back to the museum then. She couldn’t just leave Tom there. She made her way to where she had left him and, on the way, she saw “Head of a Woman” still lying on the ground. She lifted it back up onto its plinth and stared at it and, for a moment, she had felt something more than the hurt. She looked around the room and saw a security camera. It clearly wasn’t working, but maybe something in the city still was? She stared and stared at the metal face and knew she had to make a choice.

She decided there had to be people out there, beyond the water, and that they must be watching and waiting. New York had been the center of the universe for so many and someone would want it back again. All she needed to do was fix it, put the city back the way it was.

She started cleaning. She began by putting Tom’s body on a bench in the center of the museum, deciding the entire building would be his tomb. Even now, she made sure there was a perimeter around that place. It was off-limits. She started on the Upper East Side and went building by building, block by block, fixing everything.

That was all so long ago. With a heavy swallow, she pushed away her memories. She focused on the road ahead of her and drove the UTV down to Sixty-First Street. She didn’t want to think about how much more there was left to do, so as she turned east, toward the river, she tried to hum. Her throat hurt, but at least there was a little sound.

She would need to go to one of her safe places to sleep tonight. She kept a food supply on top of a pillar that used to hold up the Queensboro Bridge on York, between Sixty and Sixty-First, so she decided to head there first. The once fleshy-looking bricks had been charred, chipped, and stained until the pillar almost looked like art. She climbed up, her hands and feet finding the familiar footholds, and looked out at what was left of Roosevelt Island. All of Queens lay somewhere beyond that. She imagined someone out there, someone looking back across the river at her.

Tomorrow, she would go back to that office building again. She didn’t get enough done today, but she could finish that floor tomorrow. And then begin on the next floor down. And then eventually another building, and then another. One by one, she would clean it all and bring all the bodies to the park. And when she was done, she would light a fire so large that it could be seen from space.

Then they would know that she was still here. They would come back and see that she had made everything clean again.

And then she wouldn’t be alone in this city anymore.