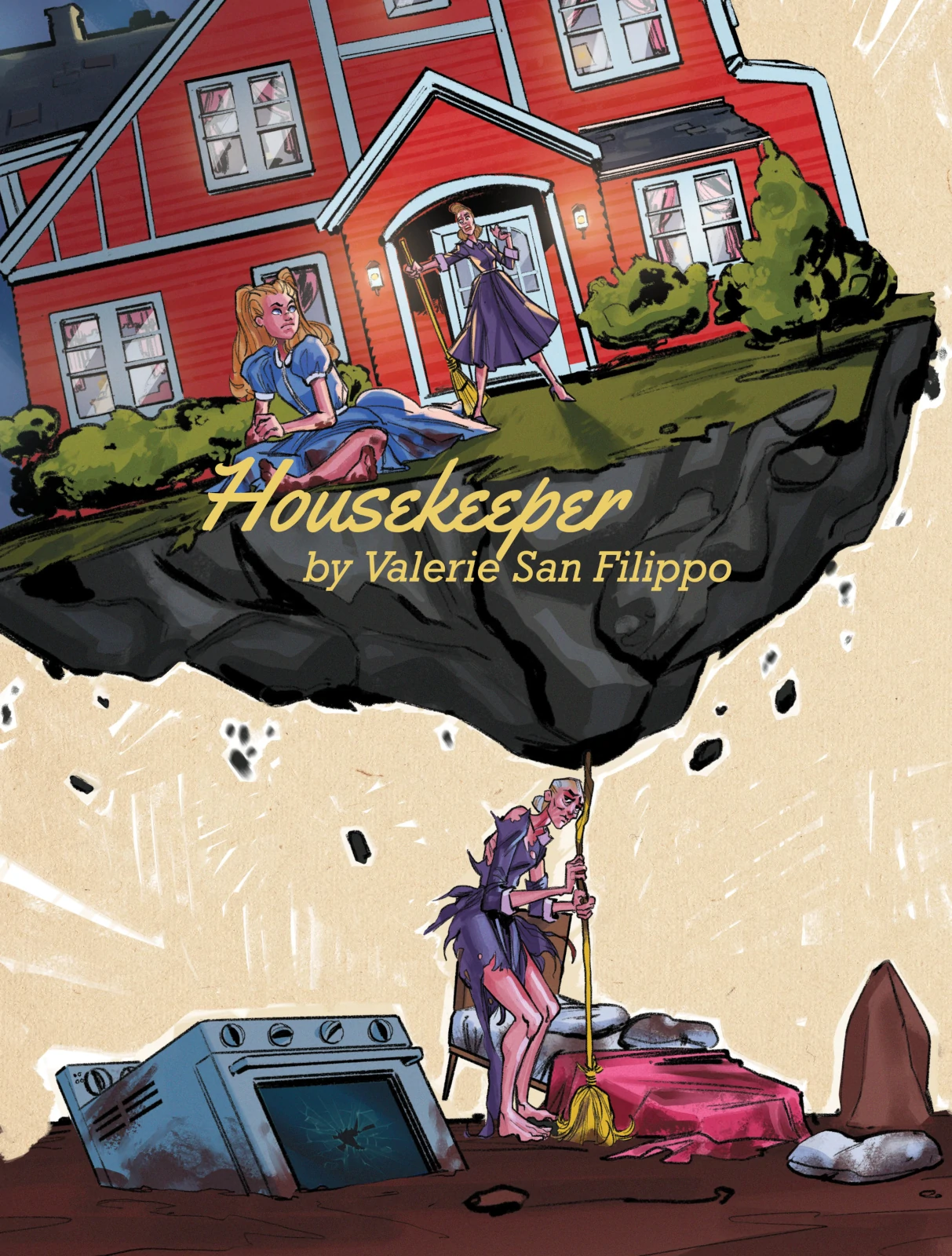

Housekeeper

Words By Valerie San Filippo, Art By Bradley Clayton

Mom always told me the floor was held up by a broom handle. If I stomped or my feet landed hard, she’d say don’t jump there, stop that, no! And if I moved too fast along the wooden floor in the hallway, she’d say things like young ladies don’t run inside the house.

One day, she kept yelling at me about how she’s the one who’s always got to clean up, and look at all the dirty clothes I make but don’t bother to wash, and how is she supposed to live in a house where I’m always tracking mud in from outside? I tried to sneak away, and she told me do you want our house to collapse? If you make our house collapse, I’ll punish you for the rest of your life.

I wasn’t even stomping. Just by existing in my mother’s house, I could make it fall apart.

I was sick of it, sick of the talk about the broom, sick of Mom telling me do this when I was trying to do that. So I shoved past her and her stupid piles of clothes all folded neat on her pink duvet. I went into my room and pulled the box out from under my bed where I’d hidden my adventure things—a jar full of rocks, a canteen, and my camping lantern. I left the rocks and canteen. I took the lantern. I had a plan.

Outside, I found the opening in the foundation and I crawled through onto mud-covered cement. My lantern made the whole place look bleached, all drips and weird shadows, pale beams, rusted pipes. My hair snagged on a crooked nail. My knees scraped in the grit. The floor sloped down. It spread away from the bottom of the house, leaving enough room that I could crouch instead of crawling. The space opened up into a low chamber.

In the chamber stood a small woman, her knuckles bent white around a broom handle. She had the same thin mouth as Mom, the same hard eyes, but she was filthy, her dress ripped at the hem, and her hair knotted up like a nest on top of her head.

My broom is stuck, she said to me, as if it were my fault. She tugged at the broom, an old wooden thing with dark stains on the handle where it had been touched. It wouldn’t budge. Wedged tight. On the ground, bristles splayed away in every direction, caked in a layer of brown mud.

“Your broom is holding up my house,” I said.

I didn’t ask for visitors. This place is such a mess, what will everyone think of me? She went on tugging at the broom, and as she tugged, she started to cry.

I’m sorry. She said. Oh god, I’m sorry. She looked up and wiped the tears away from under her eyes with the tip of a muddy finger. She blinked a bunch, her mouth open. Get it together, she told herself. Come on, it’s not that hard.

Not far away from the woman sat an old yellow stove like the one we had in the house, but this one was streaked with mud. Beyond that, I saw a bed, also muddy, with a dirty pink duvet seeping over the mattress edge. Apart from the woman’s sniffling, the chamber was quiet. Cool and damp. Secret. Like a hideaway. The air held the smell of an autumn forest floor.

“You have a lovely home,” I said.

Bullshit, she replied. Then, she started to cry again, crying harder, and she tugged harder at the handle, but the broom still wouldn’t budge. It hadn’t moved an inch.

I didn’t know how to help her. If I pulled the broom with her, maybe the whole house would come down. Maybe we could both make it out, but we would have to run. Plus, I didn’t want to upset her more. I stooped and crawled out, my hair catching on the nail again. I emerged into the sun of the backyard and went inside.

What kind of mess do you call this? Mom said. She stepped toward me and caught her fingers in a knot of hair on top of my head. Where have you been? Never mind. I don’t care. You’re filthy.

I looked down at myself, my dress ripped and muddy. Under my nails, black crescent moons. I must’ve looked just like the woman under the house. My shoes had tracked tiny grains of dirt onto the white tile, and feathered dust drifting down from the hem of my skirt. I wondered who was going to sweep it up. I wondered if it should be me.

I thought about the section of wooden floor, how with just one well-placed stomp a broom could break apart. At its most worn point, the wood thin and black with fingerprints, the handle would probably splinter in two.

Oh god, Mom said. Oh god, what will the neighbors think of us?

I stomped past her. I stood on that spot in the hall, and I made sure that Mom was watching. She needed to see me, see us, see us three stuck in this house together. And I needed her to know that I knew what I was breaking.

I bent my knees and jumped.