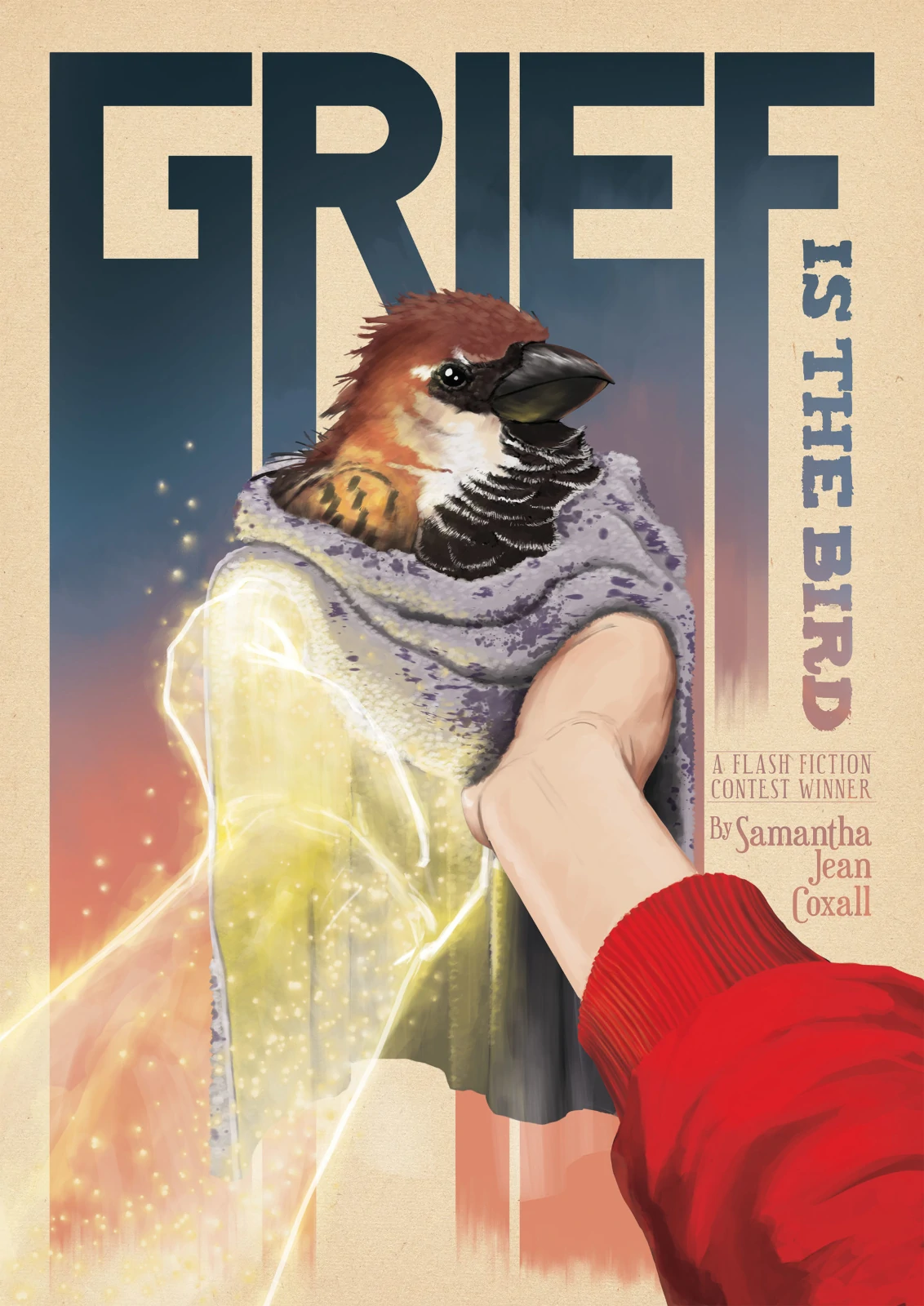

Grief is the Bird

Words By Samantha Jean Coxall, Art By Julian Mateus

My father died from a gunshot when I was in second grade. My first day back at school after the funeral, my classmates shot rubber bands from finger guns and I vomited behind the soccer net.

When my mother came and picked me up at lunch, she was in her blue sporty car instead of the gray family minivan with the car seat for the baby that was supposed to come before Christmas. If a baby did come someday and my mother put it in the car seat in the gray family minivan, that baby would be half my mother and half someone I did not know yet, and I would only have half a sibling when I really wanted a whole one.

“Still feel sick?” she asked when I slid into the front seat. She didn’t roll her eyes like usual or say, okay, just this once, and I figured it was because my father was underground and so I was an adult and could do adult things such as sitting in the front seat.

“No,” I said and picked at the nail on my thumb. “I feel better now.”

“What’d I tell you about doing that?” She often said that if I kept picking my nails, soon I would have nothing left there except wrinkled, red skin and that the kids at school would say I was gross or strange, and I didn’t want to be gross or strange, now did I? I wanted to tell her that I had lost a toenail on the playground once—picked it right out from the nail bed in two separate pieces like I was playing Operation—and that all the boys in my class had wanted to touch the place where it had been. I didn’t tell her, though, and instead I put my hands between my thighs and pressed them together so tightly that I felt something like television static in my fingertips. She turned up the stereo and I asked her to play the song where the man sang my name, but she said she had left that CD in the minivan.

When we arrived home, there was a bird on the front porch. It was black and the feathers on its face were wet and standing straight up as if it had been licked by a cat. My mother was still in the driveway with the car running, so I stood on my toes and knocked on her window with the side of my fist. She rolled it down and I could see that even behind her sunglasses her face was puffed up and ugly pink, like it was made of gum.

“There’s a bird on the porch,” I said. “He looks cold.”

She breathed in and blew air out between her teeth. She said, “I need to go back to work.”

“Can I bring him inside?”

“No. Don’t touch it,” she said. “You can put a towel around it. A little one from the laundry room. But that’s it.”

When she left the driveway, I stood in the car smoke left behind because it felt warm and a little wet. Then I went to the laundry room through the garage and picked out one of my mother’s paint towels from the pile on top of the machine. It was rough with dry paint and stained the same purple as my bedroom walls. I went through the house and opened the front door.

The bird puffed its chest out when I sat down next to him. Even though I wasn’t supposed to touch, I put my fingers up against his beak because that’s what my father told me to do when meeting a dog. Something like: let it smell your hand until its tail wags, and then you can touch him on top of the head. I knew birds’ tails didn’t wag, so I waited until my fingers grew stiff and rubbery and I could feel the frost melting wet into the back of my jeans. Then I put the towel over him, but it slid down his rounded back.

When I scooped the bird and the towel up, he felt like a cold rock in my palm. I was thinking that he could be mine. That my mother couldn’t be mad if I brought the bird inside and warmed him and took care of him on my own. She wouldn’t have to know. I’d keep him in my bedroom. Let him fly in the mosquito net around my bed that my father had called a “princess canopy.”

And if she found out that I had touched him when she had said not to and that I was keeping him in my room, I would tell her that I’d rather have a bird than a new father or half of a sibling because I knew that I could love a bird, and that this bird would have to love me back because I saved him with my own hands and let him fly in my room.

I brought the bird to my room and put him under my winter comforter, which was yellow fabric with white stitching that matched the yellow house with white shutters that my mother had painted on my purple wall. I laid him down on the pillow and pulled my comforter over him until only his shiny, black beak stuck out.

I turned off the lights and said, “Goodnight, darling,” which is what my father would’ve said to me if I was the bird and he was me.

When I checked on my bird when my mother started making dinner, his beak was still sticking out. I touched it with the tip of my finger, but he didn’t move. Under the comforter, his body had grown longer, and his toes curled tight together like thorny weeds. His beak was open like he had been screaming.

I brought him to my mother, and she threw the bird and the towel into the garbage can at the end of the driveway.