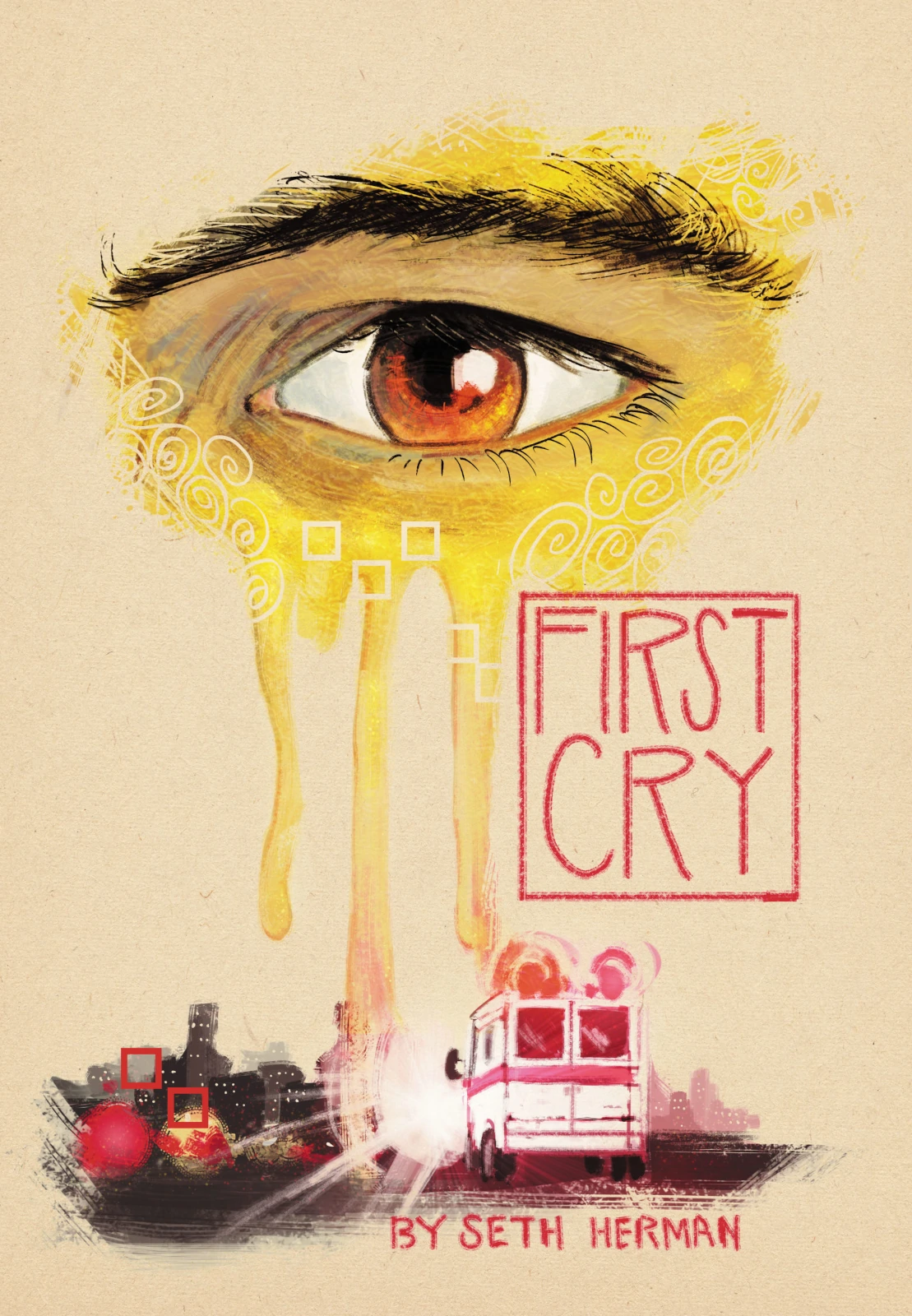

I have a complicated relationship with crying.As a kid growing up in the 80s and 90s, my exposure to pop culture consisted of a heavy dose of Schwarzenegger, Metallica, and Pro Wrestling. Which meant that amongst my friends, if you expressed any sort of emotion or thought that was less than macho, you became a…

This post is only available to members.

Seth Z. Herman

Seth Z. Herman hails from Queens, New York, where he grew up reading an unconventional mix of Clancy, Crichton, Tolkien, and Rowling. A lifetime of experiences later, he lives in Jerusalem with his family, where he teaches Judaic studies in an American seminary. When he’s not trying to figure out which genre to write in, he can be found studying Torah, training for his next marathon, or eroding his mental health by rooting for the Mets.

Hailey Renee Brown

Hailey Renee Brown is a freelance illustrator born and raised in Mid Michigan. With a bachelor’s in Zoology, she spent years formerly working as a field biologist. Moving across the country to the east coast, she also moved from science to art and graduated from The Joe Kubert School of Cartoon and Graphic Art. Hailey works as a freelance colorist and illustrator for a wide assortment of clientele, including comic anthologies, fantasy authors, and Dynamite Entertainment.