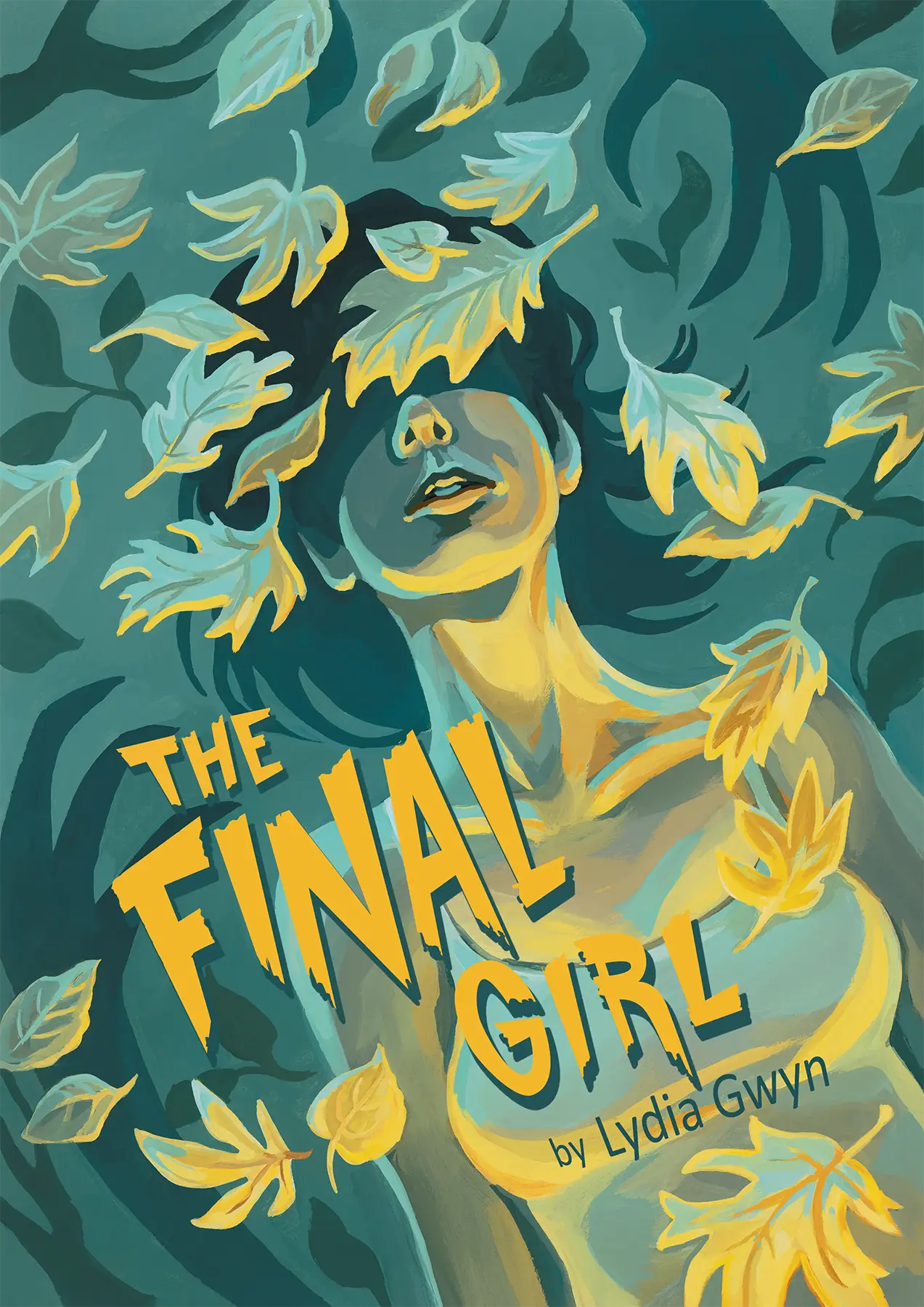

Final Girl

Words By Lydia Gwyn, Art By Lisa LaRose

They’d found her body in an empty field. A piece of her denim on a barbed wire fence. Her white handbag under a tree in the Cherokee National Forest, its kisslock loosely pecked. Days earlier, she’d begged me for ten dollars. I knew it’d go to the man who usually stood across the street watching us, but I cashed it out of my register and handed her the money. She looked ragged and tired, like she’d been running through the woods all night. Her arms were covered in scratches. I imagined her in danger and she suddenly became “Jessica.” When I first met her, she said that would be her horror movie name: Jessica. She said she might not make it all the way to the end of the movie—axe-beaten and swollen, blood on the brain—but she would at least be one of the final characters to die. You would definitely die in the first scene, she said. I didn’t want to believe her, but I feared she was right. She leaned across the bagging area while she talked, and my coworkers left their registers to come listen. There was no one in the store that time of day anyway.

You’re wrong about me, I said, and I tried to talk my movie character’s station up. I’d seen enough horror movies to know that the good girls made it through. The girls who had sex, the girls who smoked pot or got drunk in the basement, the girls whose boobs you saw while they changed clothes in front of a mirror—those girls were the first to die. I’ll be okay, I said.

Jessica did not agree. You’re too nice, she said. My coworkers, on the other hand, were tougher, and she thought some of them might survive but most would only make it about half-way through the movie. They were farm girls, girls from hollers. Girls whose fathers taught them how to throw a punch without telegraphing.

We were all impressed by Jessica. The loose men’s pants, the tiny tank top, all the rings she wore. The blue bandana around her neck. The homemade tattoo behind her ear. At first, we wondered if she was a thru-hiker. Middleton was a secret oasis on the Tennessee section of the Appalachian Trail, and MidMart was the only grocery store in town. We saw a lot of hikers, but Jessica didn’t carry a backpack, only a small white purse that she wore across her body. And she stayed around longer than any thru-hiker I’d met.

Over the next few weeks, Jessica began coming in early, just after the morning meeting when all the managers had headed back to their offices, to chat. We talked about horror movies, about the Poltergeist and Exorcist curses, the people who died or almost died, and about Jason Voorhees’s mother. One day I asked her about her own mother. Jessica didn’t look old enough to be on her own. She married her boyfriend, she said, and kicked me out.

We noticed Jessica wore the same two outfits over and over and every day that same blue bandana, so we all started donating to what we called the “Jessica Cause.” We gave her our old clothes and our books. We gave her lipstick and tampons, and a little of our money every payday.

But then she stopped coming around. We waited. We watched for her brown ponytail, her spaghetti straps through the sliding glass door. The man from across the street was gone. When the officers came in for Cokes just before they started their shifts, we always asked them about Jessica. That was the only name we had for her. They knew who we were talking about, but they never had news. We didn’t know for sure, but we got the feeling they weren’t really looking. But we didn’t stop. We kept watching for her blue bandana, her soft gait down the aisles. I’d stand behind my register, feeling transparent to the shoppers and my coworker, and twist the heart pendant on the necklace my mother had given me for Christmas. I’d twist it until I felt my fingertip purpling.

Then one day the officers said they’d found her. They told us she’d bled out. Later, one of the girls had to explain to me, Bleeding out means you bleed until you die.

We talked about Jessica all that day, but then much less in the days that followed.

All summer, I picked up shifts no one wanted and followed my parents around the house. Helped my mother repaint the living room. Chopped vegetables with my father for the stews he made. I dreaded being alone. I wanted anything other than to remain alone and unseen, hidden away in my bedroom. What had caused her to bleed out? There had to be an instrument somewhere that fit her wounds precisely. And the person who used it was still out there.

That fall, I would be going away to college, and I knew what sometimes happened to college girls—how quickly walking across campus at night could turn into its own kind of horror movie. I thought about Jessica’s prediction for me, my fingers rubbed raw from twisting my locket. I couldn’t stop seeing Jessica dying in that field alone at night. I could feel the blue of the stars above and the thin night air. I could see Jessica agape in the pale summer grasses, the dirt soft under her nails, the blood pooling under her shirt.

I twisted the locket, cinching it tight around my fingertip until a numbness came, until my hand felt as invisible as Jessica was, long before she’d been killed.