Drone

Words By Matt Jones, Art By Ryan Gajda

I joined the Navy for its poetry.

Salt-spray icicles, jousting narwhal, wind-scarred cliffs—my love of lucid imagery led me to the Arctic, where the sea is almost black. I was an ink-stained naval officer, scribbling in journals, collecting images. A sailor on his own watch, with the northern lights overhead.

When I first arrived at the army base in Petawawa for pre-deployment training in the spring of 2010, I’d been at sea so long I got land-sick when I stepped ashore. Mark was my friend, a burly infantry officer, the guy who showed me how those damn buckles on my rucksack worked and slowed to jog beside me on obligatory morning runs. He ran a platoon of soldiers all through his infantry training, conducting night raids on his fellows, glued to his rifle. Before, he was a student, even got his Masters in theology, but joined the Army claiming, “It’s here—in the Army. I can do more good for the world in Afghanistan than I can as a priest.”

But I wasn’t about to fold my hands in prayer. Instead, I scribbled impressions in a battered journal throughout our pre-deployment training: rucksack marches, briefings, inoculations, presentations, and applying tourniquets to slabs of raw meat. I had a weekend to visit my Mom before I left, which we spent drinking tea in her kitchen, a dream catcher dangling overhead. She pretty much lived in that kitchen, meditating each morning at the table and chatting on the phone with her sisters every evening. That weekend, she was a mess of grief and curlers, asking over and over, “Why do you need to do this?” and, “Why can’t it be someone else’s son?”

At the end of the weekend, when I turned to leave, she clutched my arm. By the look on her face, I could tell she thought I wasn’t coming back, or—if I did—I wouldn’t be the same. “Please don’t worry, Mom. I’ll be fine,” I said.

“That’s what all the sons who go to war say.”

Of course, she was right, and I could only pity her powerlessness—there was no backing out of the tour at this point; I already had one foot on the plane. I said, “If I’m ever going to be a great writer, I need to experience as much of the world as I can.” She let go of my arm.

But her words rang in my ears on that midnight flight over the Atlantic—as we passed over Europe, and when we dimmed the lights over Afghanistan, becoming a shadow flitting through clouds. I carried that weather-worn journal with the rest of my gear to the Big Ass Tents, where we stayed for two days in 120-degree heat until vacancies opened in the barracks. The air-conditioning, in the cells that welcomed us, felt like a nirvana of breezes despite their constant drips.

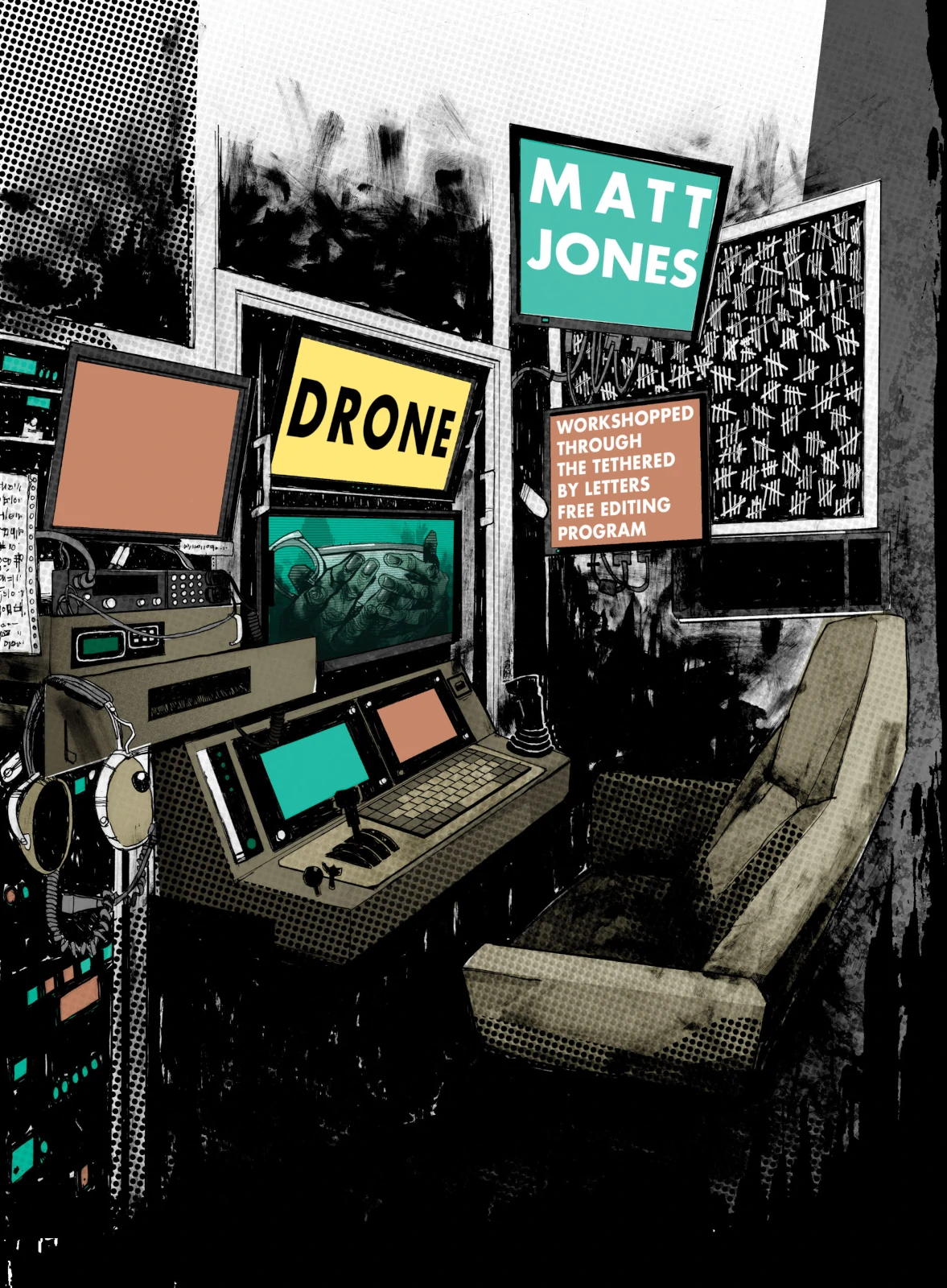

The war played out through drone feeds. During those first months, I didn’t read or write—at least not until the summer’s fighting season blunted to the winter’s lull—but I memorized the map down to the villages and learned the difference between a section, company, and brigade. Mark said, “We are always in a state of transformation. We are always becoming the person we need to be.” I told him he was becoming an asshole. Mark was too much of a monk to feel at home in the ops center, a clash of sleek technology and unpainted plywood, walls bare but for dozens of monitors. Most of the screens were drone feeds. Several scrolled with sanitized anti-poetry—the combat chat, our means of passing info to the troops. The combat chat was not scripture, but it did have miraculous powers. It could transform a person, smeared over a poppy field by a five-hundred-pound bomb, into “1 x KIA.” There was no music; there were no mantras. Only the squelch of radios and the burbling of a coffee pot in one corner.

Our eyes were the drones’ eyes. Depending on the camera, the images were either colored and pristine or black and white, heavily pixelated and gritty. Sometimes the drones with the most missiles were the ones with the worst cameras; it was easier to strike a blob of pixels than a person. Or so we thought, late at night, watching the roads unfurl like spools of barbed wire while jostling the coffee pot. Our team was a ragtag band of soldiers like Mark, one lone sailor (me), and a few Air Force types like my buddy Tictac. Tictac was an air traffic controller by trade and a six foot four, blue-eyed titan by birth. As a team, we had gathered from all across Canada, assembled in Afghanistan, and synced despite our different skills. We wore arid-patterned combats and 9mm pistols, working twelve-hour shifts, seven days a week, until the reprieve of leave came every few months.

Tictac counted sixty-eight rocket attacks by the end of his tour. Each time, we huddled in the dust as insurgent-fired bombs rained down on the base and burst with shrapnel. Some of the explosions were so close they’d shake the walls of our compound or shower us with gravel. But eventually rocketing became so mundane I’d scribble in my journal while waiting for the camp’s loudspeakers to proclaim, All clear.

Sahar was a defiant boy; he threw stones at coalition tanks as they drove past, skipped prayers to play catch in landmine-strewn fields, and ate all the food in his mother’s mud home. As he grew older he emulated the Taliban warriors who used his village as a haven. He affected their speech patterns, their way of walking, listened to them read passages from the Koran. One evening he booby-trapped the road near the field with homemade explosives: long tubes packed with nails and cutlery. The next day his mother was hoeing a wadi with five other women when someone yelled that something happened to Sahar in the nearby field. She ran south from the village of Zangabad. It had recently rained and the woman—with her retinue of anxious friends—muddied the hems of their black burkas. The women spilled onto a field of blooming grasses and flowers, where an hour earlier we had fired missiles at Sahar; after the smoke cleared, you could still see the blood raining down. We watched the mother search for pieces of her son, collect each fragment in a wicker basket. She was thorough, running her fingers through the new grasses, pausing only to beat her breast and shriek. Sunset painted the field orange by the time the basket was brimming. She labored with it alone all the way back to her village, refusing help from the other women. The flies buzzed around her; when one of the larger pieces shifted in the basket, she adjusted her gait.

Attempts to rewrite the story of Sahar with a happy ending came to dominate my writing. These, as well as records of violence and sterile combat chat, drowned out the once-fanciful images of krakens and mermen in my journal. The only exotic creature I saw was the one that Mark, Tictac, and I had become: a three-headed hydra. We resolved crises, sending troops to caches of homemade explosives, deploying helicopters to evacuate wounded soldiers, or recovering a crashed aircraft. These were the feel-good moments, the best times—when what we were doing was just.

But most of the time, the hydra was a predator, hunting roadside-bomb emplacers down the winding Panjwa’i roads. We deployed our best assets—drones, jets, bombers, tanks, artillery—for the task. Almost every day, Mark would say, “Nothing is more important than making sure the people we kill are fighters, not farmers.” After every strike, we would watch the body for an hour to see who came to claim it—whether they were carrying rifles or rakes.

After only a few months of shredding people with shrapnel, we were hard-bitten, cynical, and sarcastic. Beyond the scant hours of non-work we spent at the Kandahar gym just outside the bunker-shaped Canada House complex, our only outlet was gallows humor. A man bleeding to death became a “gusher.” A woman’s face, frozen in the rictus of a scream, was her “o-face.” If a strike did not successfully kill every “target,” the survivors were “squirters.” Mark was the most confident, but I imagined new ways to layer artillery fire on top of missile attacks; this pleased the General, my creativity at work. We were a new species of monster who smoked cigarette upon cigarette after every strike.

We kept score on a little chalkboard: for every successful strike, we added a line. After a hundred days, this calendar was packed, unintelligible, and we abandoned it. By then, they were all blurring together—our victims. I never actually knew their names. I gave them a second life in my journal, or attempted to, at least.

We spotted two young Afghans trudging east from the village of Mushan. They wore loose-fitting, pajama-like garments, bone white and whipping in the wind. One carried a heavy satchel from which the other unloaded red gasoline containers—they spooled out the wire, part of the trigger mechanism for a roadside bomb. Mark ordered the strike, and the Hellfire missile detonated right between them, obscuring them in gouts of black smoke. The smoke was stubborn, only showing glimpses of the two men, their clothing rent in rags. They were lying about six feet apart; the man on the left was clutching his chest, the other’s leg was smashed and twisted. Typically, we would have sent a medical helicopter for anyone, friend or foe, with these types of injuries; but not this time. They were in the middle of no-man’s land, where Taliban had fired rocket-propelled grenades at our recovery craft the week before. So instead we watched them die for forty-five minutes as they reached for each other, one last spark of warmth.

“Maybe they’re brothers,” I said.

“Maybe when you’re dying everyone is,” Mark replied.

After the night shift, Tictac and I would walk back to the barracks together in the early-morning dark; we headed down the camp’s main road, which was broad and rutted from the trampling of tanks. On these streets, the only plants were stunted, more thorn than leaf, often growing from piles of junk metal or shaded by looming concrete barriers. We passed the poo pond, painted eerie and gray by the moon, where the waste of all the soldiers brewed in one massive cauldron. This time, Tictac was quiet; I prodded my friend to say something.

“I don’t want to talk—it doesn’t fucking matter,” he muttered. His pace quickened as we moved in silence toward our plywood barracks.

The next day at work, Mark was sharing gummy bears and hot-spiced peanuts. The guy got a morale box from home every week or so—treats from his pregnant wife. They spoke quietly for two hours every evening over Skype. I said “hello” to her once and waved for the camera. A woman in her mid-twenties, hair long over her swollen middle, returned my wave with a pale wrist and faint smile.

Mark used to say that every sin in the world was his own fault, that each one of us was responsible for the evil around us. One evening he found me watching videos of drone strikes on repeat: predator porn. I turned to him and said, “Mark, come look at this! This is the guy we got last night.”

He shook his head. “The more people I see killed, the less it means. And if killing people doesn’t mean anything, nothing means anything. And at that point you might as well hand in your ticket.”

Have you heard of the tragedy of Nakudak? Coalition forces hired local laborers to assist in the building of a road from Kandahar City, following the snake-like Arghandab River to the southwest, past the villages of Mushan and Zangabad. The purpose of the road was two-fold: first, it would enable villagers in these troubled areas to carry their goods to farther markets, thereby increasing their quality of life; second, to allow the movement of coalition tanks and LAVs to these insurgent outposts. By some coincidence, twelve of the workers we hired for the road were from Nakudak, a village fifteen kilometers to the east. As the laborers trudged home after work one afternoon, ten AK47-carrying Taliban on motorcycles circled the workers, and herded them at gunpoint into the village square. As the women, children, and old men watched from the doors of their huts, the Taliban forced the laborers onto their knees. One of the Taliban warriors—a grizzled veteran with scars on ropey forearms—produced a set of gardener’s shears from the back of his motorcycle. He strolled up the line of laborers, hacked off their ears and noses, and tossed the fragments in a heap.

After six months, I was losing parts of myself too. Journal entries had become clinical descriptions: how many bombs dropped, how many KIA, how many squirters. I was drying up, but the desert became lush when the skies opened during the three weeks the Afghans called the rainy season, when all the roads turned to mud. These torrents revived the opium, bloomed flowers, filled trees with starlings. With boots caked in thick mud and roads useless to Canadian soldiers and Taliban alike, we enjoyed an unspoken truce.

When the mud dried, the heat in the gym rose to 120 degrees; Tictac suggested we take our workouts outside. Sand whipped against the scattered gym equipment and piled against giant tires, stripped from a US Stryker. We flipped those tires back and forth along a ruined wooden boardwalk, dust clouds rising with every rubbery thump, until our hands were blistered and we tasted blood. Sometimes we worked out so hard we couldn’t even dream. When I did dream, I would dream of the mother—the one with the basket. I wanted to believe she could heal from that loss we visited on her. I tried to picture her laughing, restored to prosperity. But I couldn’t. The image always melted away and she was left crippled, unsmiling, gaunt—gnarled fingers clutching a cup of tea.

On September 11th, 2010, a minister in the southern United States declared that the anniversary of the World Trade Center tragedy would be known as “Burn a Koran Day.” The event generated serious media attention; President Obama gave a damage-control press release, but I’m sure most people in the US merely dismissed Burn a Koran Day as misguided and ignorant Christian fundamentalism, and so it was. But in Afghanistan, the response was explosive. Riots began in Kandahar City, twenty kilometers north of our base, spreading west into our area of operations and infecting the outlying towns. Bazaar-e-Panjwa’i’s riot was particularly bloody, as thousands of Afghans took to the streets. A fire kindled in the poor section’s squalid tents and spread to the downtown shops. Mosques and bookstores were incinerated in the blaze, gilded Korans reduced to ash, and in the streets several people were trampled by the mob—crushed and suffocated by sandaled feet. The Afghan police arrived and formed in ranks in front of the rioters. As I watched, the policemen fired their AK47s into the crowd in automatic sprays. One man had his knee blasted inside out. He crawled a few feet into an alley, dragging his leg behind him, where he rocked and rocked. I can still see another man’s split face after he took a bullet—his cheek flapped over his beard. He fell out of view and the drone zoomed in on an old woman whose hip was shattered by a round; she spun, as if dancing, before another shot felled her. As the police refused to evacuate the wounded, we sent helicopter after helicopter for eight hours straight.

It was easy for us to feel powerful when we could summon helicopters and save lives. Other times we tried our best and people died anyway. Once Tictac and I watched a marketplace through the drone feed; vendors hawked gaudy glass baubles and carpets. A woman walked through the crowd, obviously pregnant, in her burka. She paused to rest at the far side of the marketplace and leaned against a crumbling stone wall. A flash—for a moment the screen was whited-out. When the camera refocused, I could see the woman had detonated an IED which tore through her body. She was lying on her back in a growing pool of blood, legs severed under the knees. Her blood spurted from stumps. She clutched her belly, wide eyes darting back and forth. She struggled to sit up. I started barking at my guys to get a helicopter in the air, and we managed to deploy one in less than a minute, while men in the marketplace gathered around her. As the woman’s feeble kicks got weaker, the helicopter landed, and two paramedics and a translator emerged. But the crowd didn’t let them get close, no matter how much the translator pleaded. The men just huddled around the woman in a semi-circle, pushing back any attempts from the paramedics to aid. The spurts of blood from her torn limbs grew weaker. As the pool expanded to a pond, we could only watch.

I thought of my mother, the way she clung to my arm in her curlers and tried to stop me from walking out of her kitchen. Staring at the hem of the bloody burka, I felt something tear loose from my chest and fall away. I didn’t know what I had lost, only that it was precious, and it had disappeared.

Tictac was doing no better than I was; his hands were clenched on the edge of the big map. He said, “I can’t believe this. I don’t want to see anymore. I’ve seen enough for one lifetime.”

After work that night, I knocked on Mark’s door in the barracks. I heard a woman crying in his room. He cracked the door to explain that his wife had miscarried. She was home from the hospital and her sobs echoed through Mark’s computer speakers: “You did this to us…all because you had to go on your little army vacation. I can’t believe you left me at home to deal with this by myself.” I had never seen his shoulders so slumped; he was sent home on a plane the next day. We didn’t get a chance to say goodbye.

The next morning, Tictac didn’t meet me at the gym, and I worked out alone in the heat. Turns out, after we watched that woman die, Tictac had walked back to his room in the barracks and wrote a lengthy note to his father. They found a moist towel in his room, so I guess he’d grabbed a shower before leaning up against the wall and putting his pistol in his mouth. Military police heard the blast of a 9mm and found him slumped over on his bunk, a red spray of blood and brain and bone on the wall behind him.

After my workout, I returned to the barracks where medics were carrying out the body. I should never have looked at Tictac’s face as he was carted past with the jaw gone slack, a new peace in his eyes, his bloody hair. I was afraid he would blur together with all our victims and be lost.

My daily shift expanded to cover the hours of my two friends. I kept working; the war wasn’t going to pause just because Tictac had killed himself, and neither would I. Mark missed the ramp ceremony but I was allowed time off to attend. Hundreds of soldiers gathered in silent ranks. We waited for the bagpipes; we had lost our own voices, buried in dry throats, but the bagpipes keened for us, giving us back our grief. When it fell quiet, the silence was deeper than we remembered.

I helped heft the coffin to the airplane that would carry him home and felt his weight shift inside the casket. It was so surprising that I nearly dropped the handle; I imagined for a second he had come back to life, that we would be killers together again. But he was gone; my memory of his face was already slipping away. He had been my friend, but he proved himself a sentimental idiot who thought people were more than meat—and look at him now. He fought until he broke and left the job undone. I smoked a cigar so quickly after the ceremony that I was sick; I wiped my mouth with the back of my hand and trudged straight to work.

Time, in these last few weeks, has dissolved; I no longer track my tour’s remaining days on the calendar, though it must be nearly a year since I left the place that used to be home. I have shed the skin that was my past life: my empathy, my departed friends, that journal with its sad attempts to bring targets back to life. I am wheeling in the sky above my enemies, breathing bolts of lightning. There is only the business of the strike and the clinical study of the aftermath—the General shaking my hand. I have exceeded the zone of competence and now enjoy the pride of flourishing. I may have joined the Navy for the poetry, but it was the Army that made me an artist. My strikes are cunning combinations of Hellfire missiles from drones and supporting fire from aircraft. I haven’t had a squirter in weeks. I have outlasted my peers—I am stronger than them. In the outdoor gym where Tictac and I tossed tires, I work out alone, flipping that heavy, rubbery bastard down the boardwalk, raising clouds of dust.