Diligence

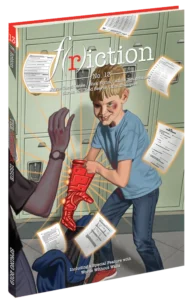

Words By Patricia Horvath, Art By Kiyoung Kim

In the photo she looks older than fifty-four. It may be the hair, silver-rinsed and loosely pinned back from her face. Or the formality of the navy-blue suit with its three-quarter sleeves, the starched shirt with the notched collar. She wears good jewelry—gold cuff bracelet, cameo ring, wedding band. The photo was taken outside the small Cape house in suburban Connecticut, one town and a universe away from Bridgeport, where she and her husband had raised my father. Rosebushes border the front steps of this home, and in her lapel is a single red bud. Her hat, a typical bit of glamorous rectitude, resembles a miniature flying saucer. Its brim shadows her eyes, which look worried despite her smile. Does she suspect her life is about to change?

My mother picks up the photo in its silver frame, stares at it a while. She wants to say something but isn’t certain whether she should. She returns the photo to my desk. “Do you know the story behind this?” she asks.

The Fairway cashier is ringing up my groceries. Yogurt, soup, quiche, prepared foods mostly because I’m too tired to cook. No salads, no sushi, no raw milk cheeses. Those have all been proscribed. She grabs a chocolate bar, scans it, sticks her fingers in her mouth, extracts a wad of gum, and throws it in the trash. I look at her, incredulous. She smiles, reaches for an apple, says, “How are you?” Fine, I want to say, except for the fact that you just put your fingers in your mouth and are now spreading your germs all over the food I’m going to take home to my husband, whose immune system is no better than a baby’s. Instead I ask her to start a new bag for the remaining items. If I had a Handi Wipe, I’d wipe them all down just to make a point, only then I’d be the crazy lady in Fairway who holds up the line while she disinfects her food.

When I get home, I wash my hands. I lay the “contaminated” items on sheets of paper towel then clean them, one by one, with hot soapy water. I’m overreacting, but I can’t stop myself. It’s something I need to do.

“Visitors are Welcome, But Their Germs Are Not. Please do not enter if you have a fever, cough, rash, diarrhea, or vomiting.” This is the sign posted outside the chemotherapy suite at St. Luke’s Roosevelt Hospital. The first time I saw it I’d found the sign alarming, but by Jeff’s second round of chemo I’d come to think of it as a sentinel—a raised hand to keep germs at bay. I knew the nurses took the message seriously; I’d even seen one of them shoo away a young boy with a runny nose. Afterward she’d rolled her eyes at me as if to say, Can you believe that?

According to my mother, the morning the photo was taken my grandparents were on their way to Yale New Haven Hospital. Several weeks earlier my grandfather, Geza, had lost his appetite; he was lethargic and had become alarmingly thin. His doctor, unable to determine the source of Geza’s ailments, had sent him to the hospital for tests.

My grandmother must have known something was wrong when the doctor asked to see her alone. Back then, the late 1950s, seriously ill patients weren’t always given their prognosis; it was left to their families to decide what, and how much, to reveal. Before marrying, my grandmother had been a nurse. She would have grasped the implications of the doctor’s summons.

“There’s a spot on your husband’s lung,” she was told. “A tumor.”

“How large?” she asked, and the doctor pointed at the rosebud pinned to her suit.

Here are some things Jeff has been told not to do: spend time in the sun, eat unpeeled fruit and raw vegetables, drink alcohol, eat raw fish, change the cat litter box, travel, go near anyone who is sick. During treatment he has to monitor his temperature; if it rises above 100.1, he must call his oncologist and report immediately to the emergency room.

We don’t know how long he’s had chronic leukemia. Two years before his diagnosis he came down with a mysterious flu-like disease, but he recovered, and except for some swollen lymph nodes in his armpits and neck, he’d been fine. One evening, though, we came home to two messages from our doctor’s office. A routine physical had revealed an elevated white blood cell count. After that Jeff entered the world of biopsies and CT-scans, blood draws, oncology appointments, and the self-effacing vulnerability that comes with putting on the hospital “gown.”

The doctor told my grandmother that her husband had, at most, six months to live. The diagnosis was advanced stage lung cancer coupled with acute leukemia. My father was granted an early discharge from the Navy so he could come home in time to say good-bye. Two months later, Geza was dead.

My grandfather was a heavy smoker, which no doubt accounts for the lung cancer, but my father and grandmother blamed his leukemia on a deep-sea fishing trip that he’d taken the spring before he died.

“He was fishing off the coast of New Jersey,” my father says. “Winter was barely over; the water still icy cold. And the boat he was on blew up. So there they were, stranded in the water, you know, for several hours before they were rescued. Meanwhile your grandmother was absolutely off the wall: ‘Where’s Gus? What happened? Nobody’s heard from him.’ And finally he came home soaking wet, bedraggled, and he got sick as hell, a fever, everything. I really believe that’s when he developed leukemia.”

Jeff’s oncologist has likened his treatment to a roller coaster ride—a slow climb back to health after each round of chemo, followed, a month later, by an immediate plunge.

The side effects were dramatic and abrupt. After the first round, Jeff’s lymph nodes shrank to nearly normal and his stomach swelled, making him look pregnant. In six days he lost five pounds. Suddenly he couldn’t stand the smell of cooked greens. Fish made him queasy and he could no longer tolerate spicy food. He reverted to childhood fare—ice cream, grilled cheese sandwiches, buttered noodles.

Three months into his treatment he developed bronchitis, his temperature rising to just below the danger threshold of 100.1. This was summer, the heat muscular. Day after day we sat on the couch eating pistachio ice cream and watching the Olympics: Gaby Douglas pirouetting on the balance beam, Michael Phelps slicing through water, and those impossible feats and physiques.

One afternoon, while watering the plants, I noticed that the living room air-conditioner was coated in a glue-like substance. The controls and grille were sticky. So was the windowsill and the lower part of the window. The other three windows were fine. I scrubbed away the filmy stuff, whatever it was, attributing it to exhaust from the double-parked buses and delivery trucks on our busy street. This didn’t make sense, but neither did a lot of things that summer. The next day the sticky patina was back. I began clearing the plants from the sill, and when Jeff asked what I was doing, I told him about the mystery grime.

He got up to look. I went into the kitchen to make iced tea.

“C’mere,” he said after a while.

The oxalis—our big, lush, thriving purple oxalis—was spotted with pimply white scales. Parasites, I suppose you could call them. We had no idea where they came from. Jeff pulled off the affected leaves and for a while the sticky film vanished, but then the oxalis grew back covered in even more scales and those scales spread to our other plants. The prayer plant and begonia became infested. The violets, those small beauties, were spared, but the spider plants in the adjacent window succumbed. We quarantined the violets in the bedroom and threw the other plants away.

The cause of leukemia is unknown. A mutation in the blood-forming cells prompts the body to produce an abundance of abnormal white blood cells—leukocytes—that begin to multiply and crowd out the healthy cells. Smoking may be a contributing factor, especially in the acute form of the disease. Being in icy water, even for several hours, is not. According to Jeff’s oncologist, there is no way my grandfather could have contracted leukemia from his fishing accident. My father’s attempt to pinpoint the source of his father’s disease strikes me as a form of magical thinking.

I’m not surprised by this. After all, it’s human nature, this urge to attribute cause to calamity. Crop failures are ascribed to an angry god, bad luck to “karma,” leukemia to icy water. There’s comfort, no doubt, in the notion that one can make sense of the senseless. If the reason for a disaster can be identified, the disaster itself can be contained, perhaps even warded off. If not, the world is a terrifying place.

There’s comfort as well in the balm of routine. Like me, my grandmother married late in life, at least by the standards of the 1930s. She was almost thirty-three when my father, her only child, was born. According to him, he disrupted his parents’ rituals: after work cocktails, wax-paper-wrapped hamburgers eaten at the beach on summer evenings, Sunday afternoons spent reading aloud to each other from the newspaper or the Saturday Evening Post.

“They were private people,” he once told me, “but always hugging and kissing. I was yesterday’s child. I was in the way.”

Jeff and I were even older when we married, and we chose not to have kids. We are a family of two with our own little habits—mornings reading novels side by side on the couch, afternoon walks to the Conservatory Garden in Central Park, martinis at the King Cole bar on New Year’s Day—not so dissimilar from my grandparents’ routines.

Another ritual: After Geza’s diagnosis, my grandmother kept his silverware in a separate drawer from the rest of the family’s. As a nurse, she must have known that leukemia is not contagious. She must have known that Geza’s condition could not be made worse by contact with someone else’s fork, especially when she washed those forks—and knives and spoons—all together. Yet she took care to isolate his utensils. This act gave her the illusion of control. False comfort is comfort nonetheless.

I never fully understood the story of my grandmother and the silverware until the day I found myself washing every single item that Fairway cashier had touched after jamming her fingers in her mouth. Ridiculous, I know. Those Fairway bags had been on the subway, that dirtiest of places. People sneezing, coughing, tossing food wrappers under their seats, wiping their noses, touching the poles. It would be impossible to create an antiseptic world and, even if I could, who’d want to live in one? Yet there I was in my purple rubber gloves sponging down the yogurt and milk containers, dropping the apples in an iodine solution, bleaching the countertops. I couldn’t help myself. I couldn’t help Jeff either, not really. I could sanitize every surface in our apartment, but it would not make his leukemia go away.

So what were we thinking, my grandmother and I, two women at a kitchen sink fifty years apart? Women smart enough to know you can’t wash away cancer, not with all the soap in the world.

I picture my grandmother all those years ago running silverware under water so hot it scorches her hands. There is a day, not far off, when her diligence will no longer matter. She knows this. And perhaps, as with me, her actions are less a way of eradicating germs than of keeping that knowledge submerged.

After six rounds of chemo, Jeff’s cancer went into remission. To celebrate the end of chemo and the beginning of this tentative new phase of health, we went to the plant store. Flowering cacti, a begonia, two spider plants, something called a braided money tree—we bought them all. My mother gave us another oxalis. So far, these new plants have been healthy, unblemished by blight.

What caused the infestation to begin with is something we’ll never know. And so we take precautions, examining the plants each time we water them. Because the disease can return at any time, we have to be diligent. We feel the leaves for stickiness, inspect them for scales, prepared to sacrifice any unhealthy plants. In this way we hope to forestall calamity. It’s all that we can think to do.