Breaking Through Borders: A Pioneering Writer Feature with Silvia Moreno-Garcia

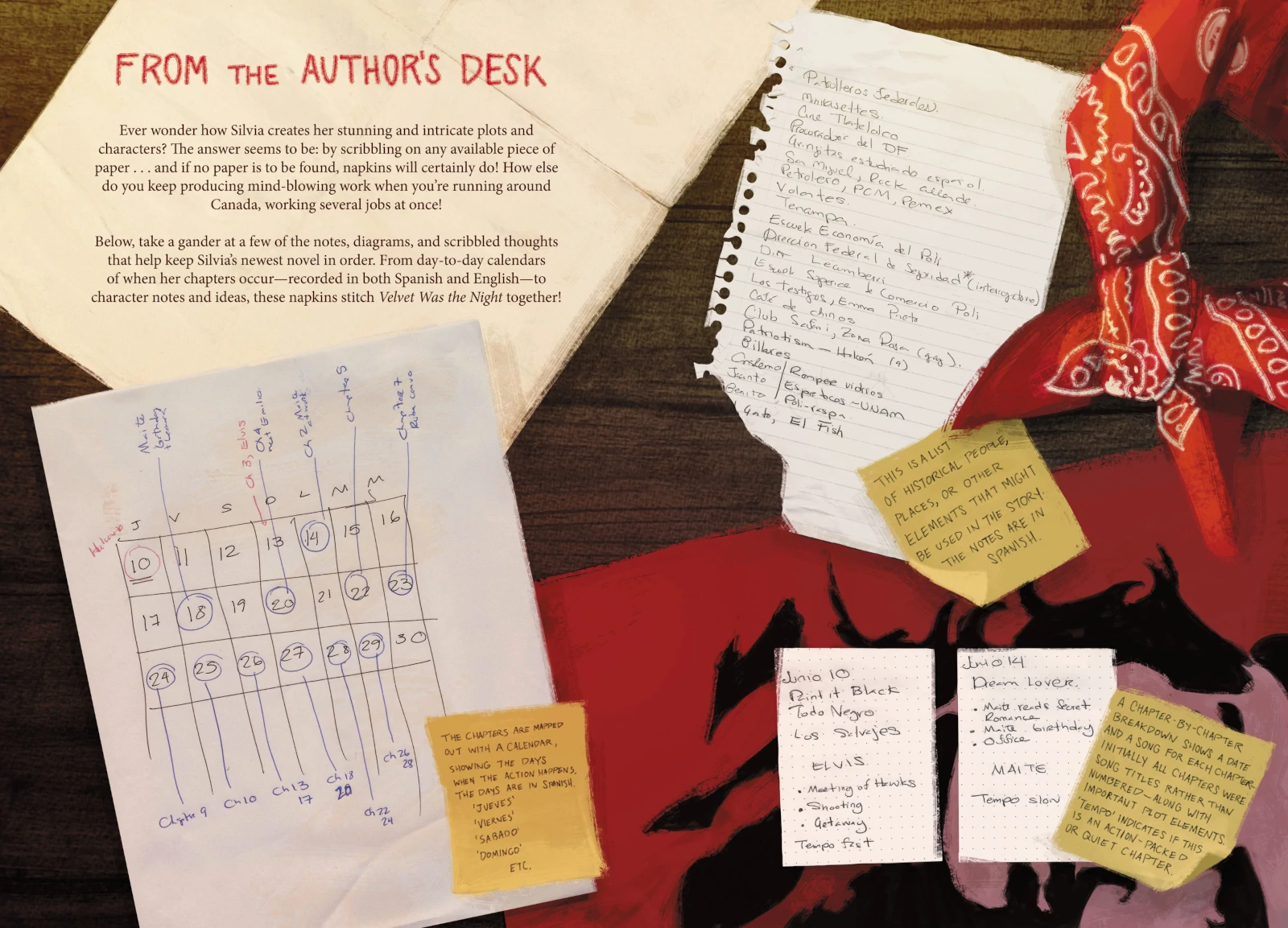

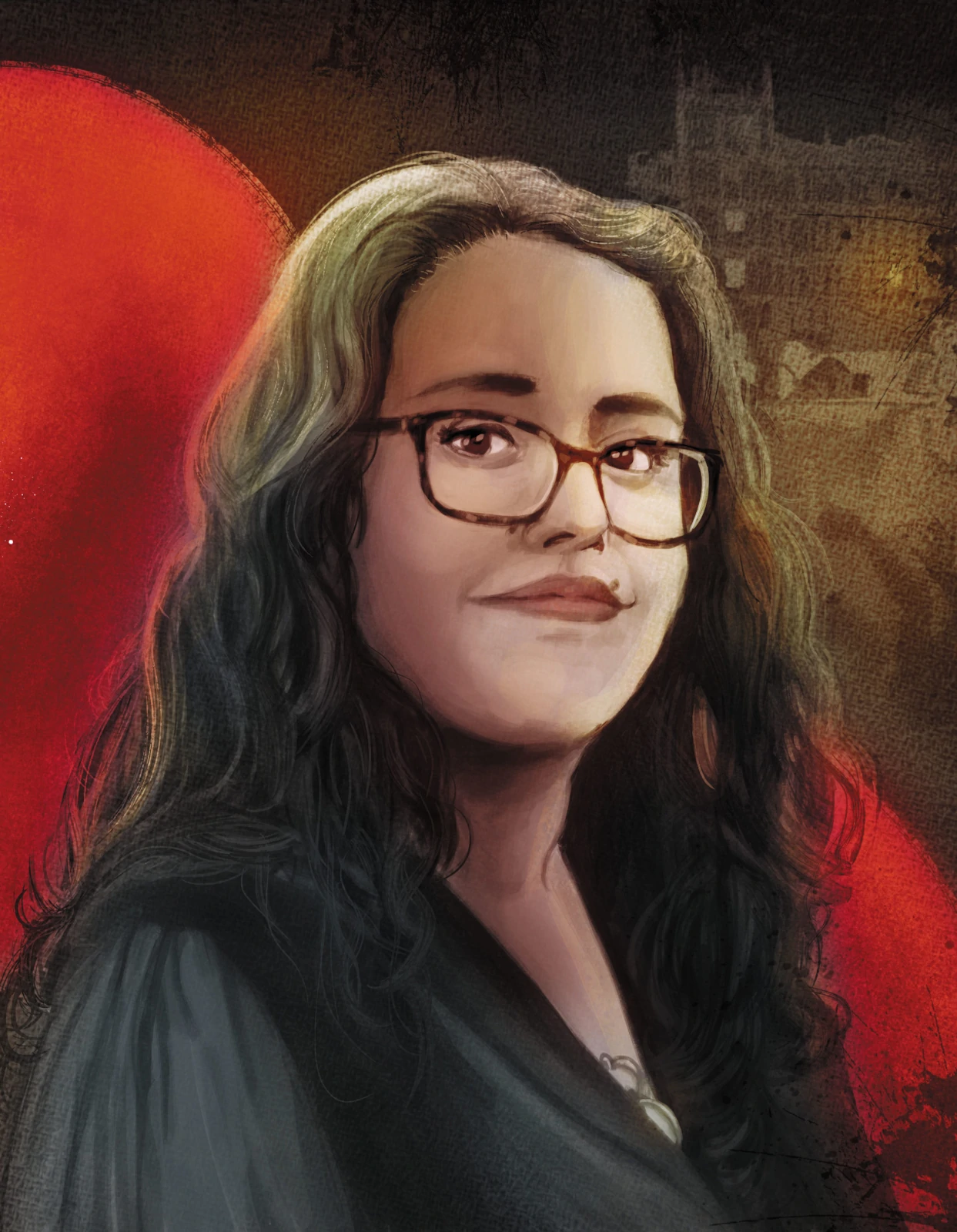

Words By Silvia Moreno-Garcia, Art By Hailey Renee Brown

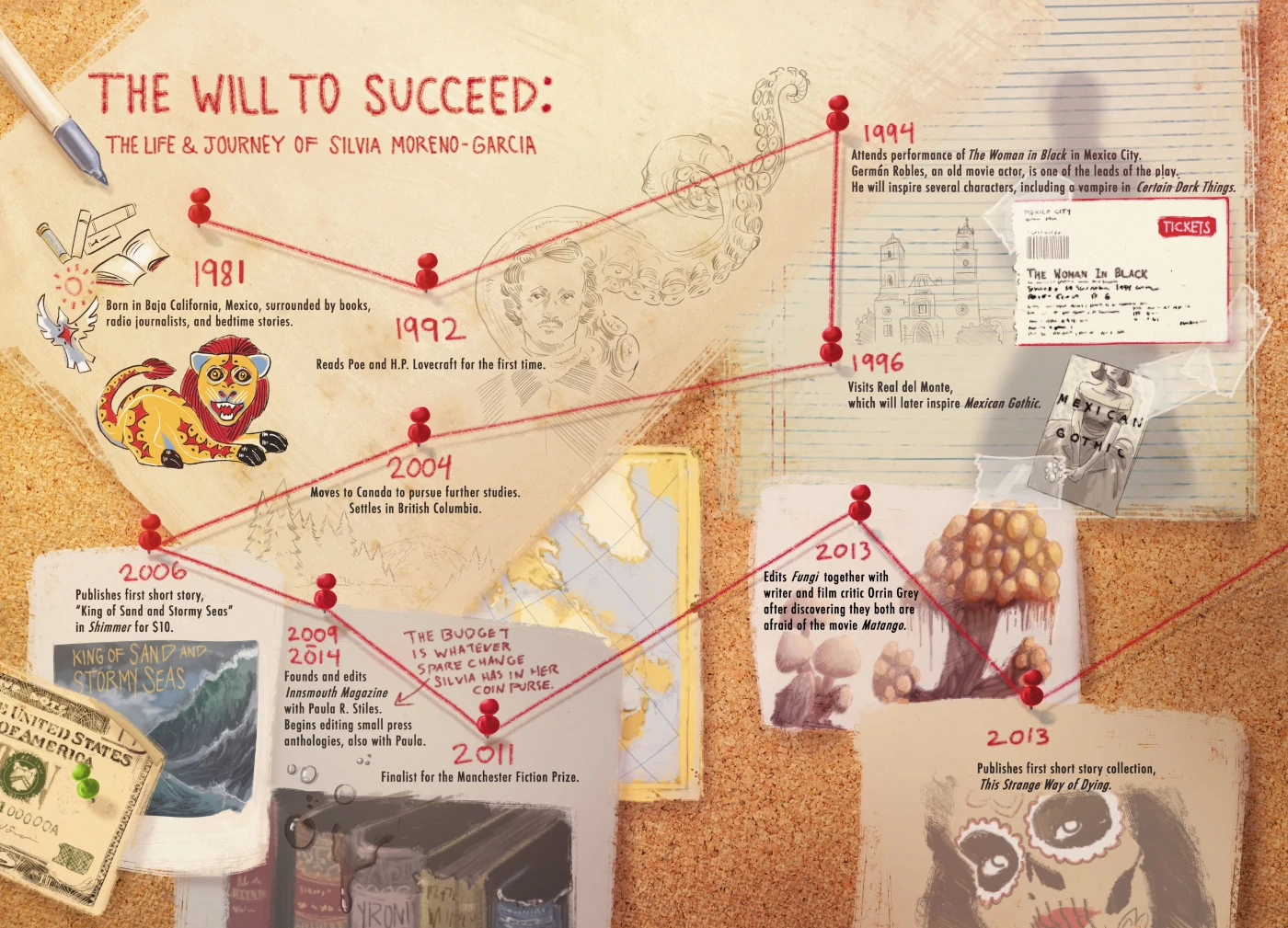

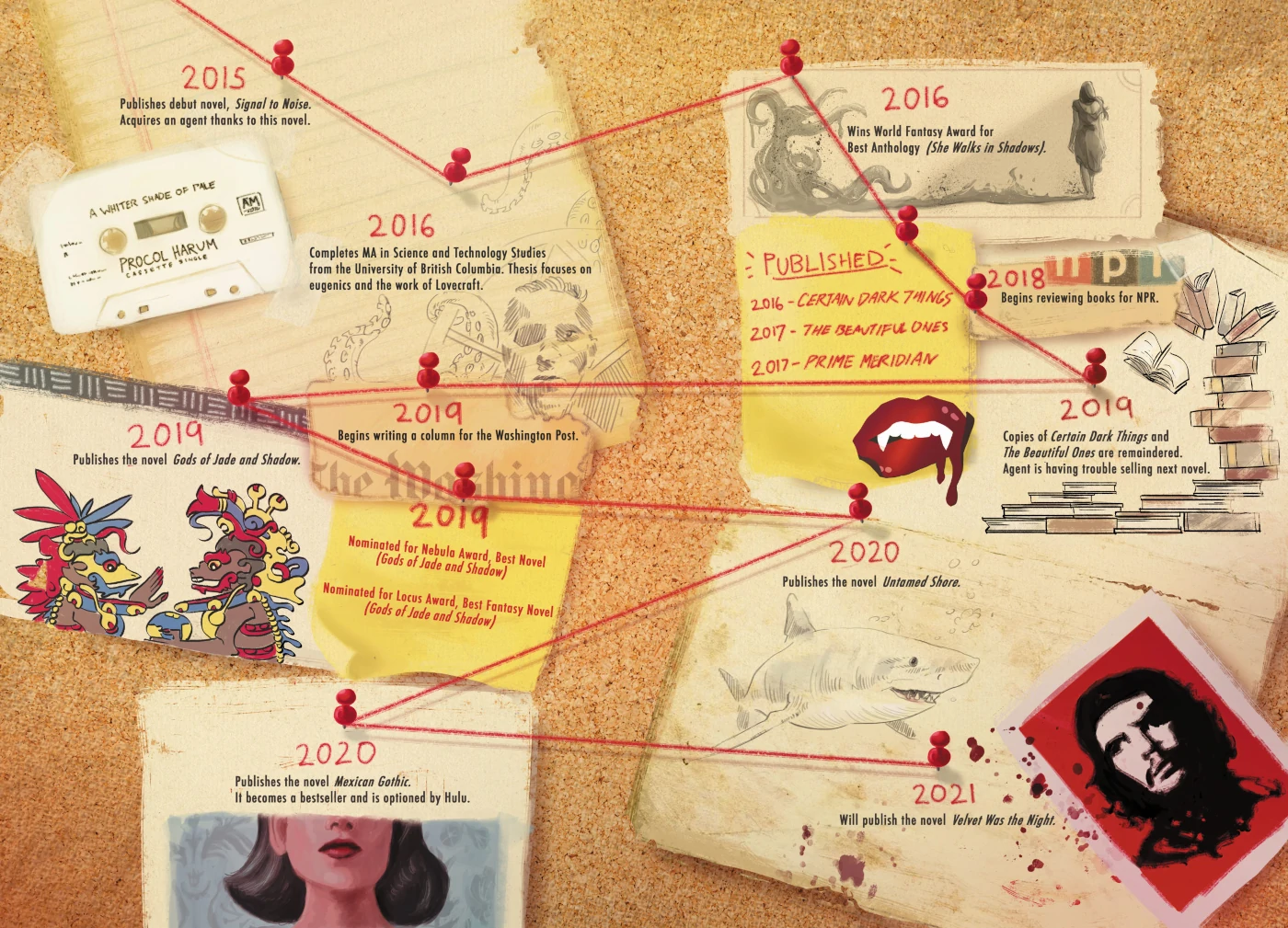

From short fiction to long form, Silvia Moreno-Garcia’s work wins awards, bends genres, and subverts expectations. She is the bestselling author of the novels Mexican Gothic, Gods of Jade and Shadow, Certain Dark Things, Untamed Shore, and several other books. She has also edited multiple anthologies, including the World Fantasy Award-winning She Walks in Shadows (a.k.a. Cthulhu’s Daughters).

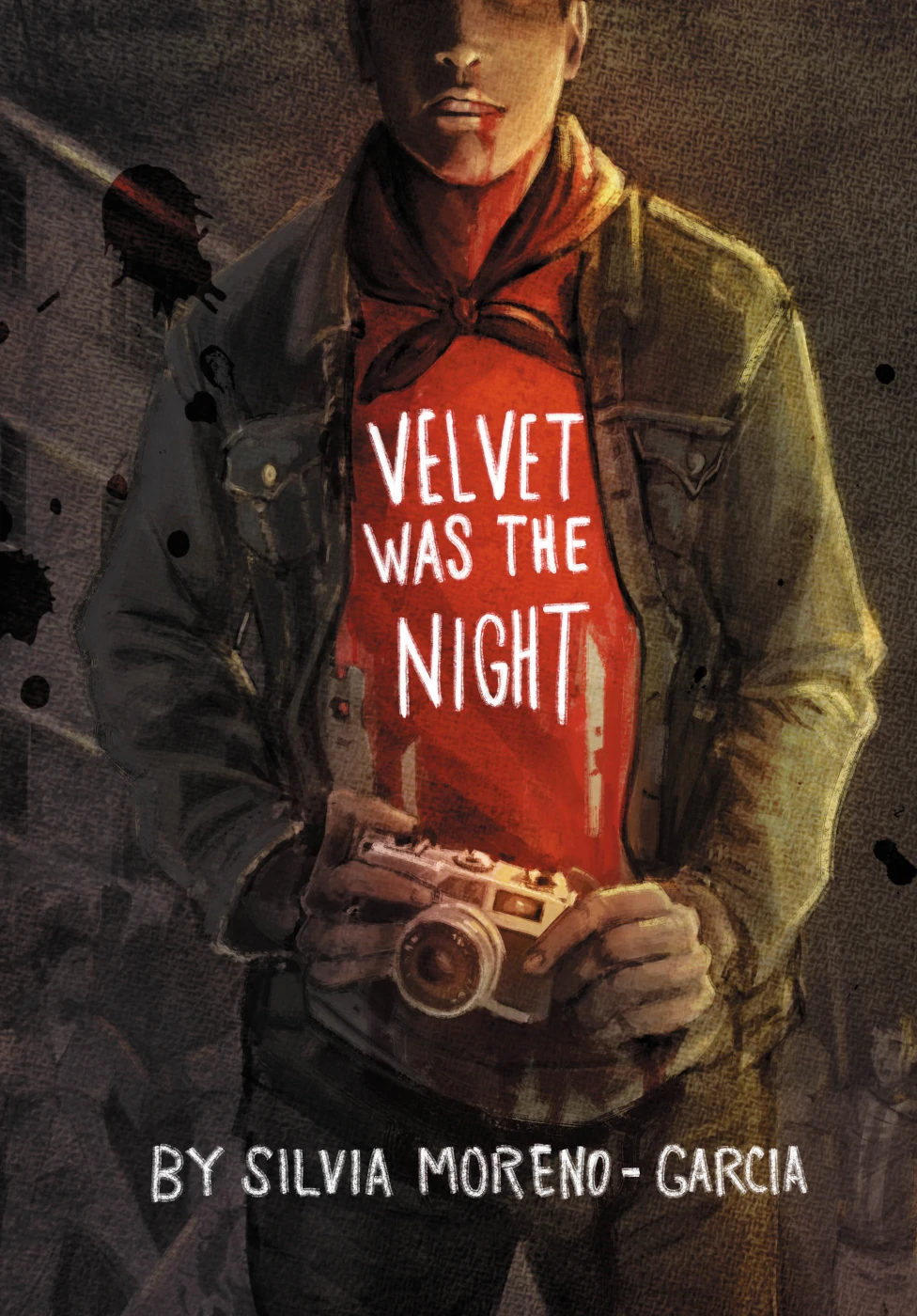

She began writing short stories to feed her family and now her latest novel has been optioned to appear as a limited series for Hulu. For most writers, these awards and notoriety would be reason enough to slow down and enjoy—but not Silvia Moreno-Garcia. She has new novels slated for release this year and next. We at F(r)iction are elated to bring you an excerpt from her novel, Velvet Was the Night, due out later this year.

An Interview with Silvia Moreno-Garcia

by Dani Hedlund

Where does your love of stories come from?

When I was growing up, my great-grandmother used to tell me stories just before bedtime about her childhood during the Mexican Revolution and folktales. She didn’t know how to read or write, so everything was spoken. My parents had a lot of books. They worked as radio journalists and they loved reading. That was basically the only thing they had because that’s not a profession where you have a lot of money. It wasn’t back then and it’s probably even worse now. But the one thing we did have all the time were books. They put a big premium on occasion and on reading.

Why did you want to write stories instead of following in your parents’ and great-grandmother’s tradition of oral storytelling?

I like sound and music, but I was never particularly fond of radio. I grew up in radio cabins. In that world, but it wasn’t necessarily what I wanted to do for a living. Initially, I thought I might want to be in print communications, in the newspaper world—but that was around the early 2000s when the communications landscape began to explode and all the newspapers and magazines started closing.

I gave up on journalism and I also didn’t quite like it that much in the end. I worked for a bit when I moved to Vancouver and, after I graduated, I worked in video production. That was kind of interesting because I was the only woman in the whole place except for the receptionist. It was very male-dominated, and the schedules were really hectic. It wasn’t conducive to having a family or being a woman. My shifts were erratic, and it was not well paid. I didn’t work very long there and I switched to corporate communications, and that’s where I’ve worked since. I’ve worked for the University of British Columbia in the Faculty of Science for almost nine or ten years, so I’ve only done communications to earn a living. But it hasn’t been radio or any kind of mass media, it’s been institutional communications.

Talk to me about the first time that you were published as a fiction writer. What did that look like and how did that affect you?

I was paid ten dollars for my first story, or one of my very first stories, in a magazine that doesn’t exist anymore called Shimmer. I needed money and back then we didn’t have a lot of money, so I was working in video post-production and I was also trying to freelance around the city. I was working for this little rag that they gave out for free when there were still print publications in corners. They paid me thirty or thirty-five dollars a pop for a story.

When things started going downhill at publications, sometimes they didn’t pay me with money, they paid me with food coupons to restaurants. I would take my family to go eat at a pub or a bar. I remember one time we went to a bar with my son and it was not a crowd for a baby, but we were there because we were trying to eat as much as we could and put as much as we could in my purse before we went home.

When I started writing, I sold to very small science fiction and fantasy publications. I was happy because if I could manage to write with the baby or my son on my lap, I could write a story. If I sold it for forty or fifty bucks that was extra cash. For me, it didn’t matter that it was only forty or fifty and I figured I could write quickly and efficiently.

I don’t write short stories anymore very much, but back then I was writing a lot of short stories and I thought if I could sell one every x-number of months then we could have an extra fifty bucks. I started writing because I was depressed, I needed money, and it was the only thing I knew how to do. I had no other skills I could apply. The only thing I had gone to school for and knew how to do was communications. And I knew how to write. I wrote short stories and I thought I would write my way out of the economic situation that we were in.

Did you ever wonder whether or not you were good enough? You’ve written and published a lot, all while feeding your family. What was it like to write in those conditions?

Not as bad as it sounds. When children are small they tend to sleep quite a bit. I had this little kind of crib thingy that I bought and I would put my son in it and rock him with one foot while typing. Then when he wanted to play or if he needed a change, I would get up.

My husband was working two shifts waiting tables at two different places in order to pay the bills. We had immigrated to Canada, so we didn’t have anybody and we didn’t have money for a baby-sitter. I just worked around my kid and I got pretty good at working quickly and using all my spare time.

Most people waste a lot of time and I don’t. I’ve always worked a full-time job or more than one full-time job and so I use every second of time that I have for something and, in my case, that something was writing. I went to the United States on two scholarships and I didn’t have a lot of money so I was also working multiple jobs on campus. At the same time, I was writing papers for other students in secret. I’m used to having to work very hard to make anything out of myself and I never doubted I could write because I had done it before. I was a straight-A student, and because I was on two scholarships I had to maintain good grades. Even before that, in high school, I was a straight-A student. When I was writing and working here, I knew I could do it because I had already done it.

You have been a publisher, an editor, a columnist, you’ve reviewed books, and you have been a writer of fiction and nonfiction. How did you end up wearing so many hats and what is it like to switch between them?

Everybody at some point, I think, wants to have their own magazine and if you have enough friends in the industry, you just do it. I had been writing short stories for a while, and I was very interested in the Lovecraft fandom. I met another person who was also interested in it.

We talked together, and I said, “Hey we should start a magazine. You know, like a small book publishing company.”

At that point, I was better positioned here in Canada—I had a full-time job and some spare money—so I said, “You know, I can use my spare money to do this.”

We did it on a shoestring budget and that’s how I made Innsmouth Free Press. I was looking to showcase voices that were not being showcased. We would look at the table of contents of Lovecraftian anthologies, it was all men, they were all white, and this didn’t kind of jive with what I was seeing in the forums.

In the forums I was meeting a lot of women, I was hearing from people of color who had also liked Lovecraft. So, there was this strange thing where I thought okay, there’re these fans that like horror fiction, that like Lovecraft, but they’re not all guys. Why is it only guys in these publications and anthologies?

The other stuff I write, the column and the review, I was contacted or met people and they asked. I do the occasional book review for NPR. I met the person who runs the reviews for that on Twitter and they invited me to do one review. If you hang around long enough, people get to know you.

Out of all of those hats—publisher, editor, reviewer, columnist—which one do you think has affected the way that you write the most?

I’m thinking differently when I’m doing different things. When I’m reviewing, I’m not necessarily behaving in a Spanish mode. I’m trying to understand the text in a critical way and analyze it, but at the same time offer enough material so the reader might know if they’re interested in it or not.

That’s a different experience than when you are looking at your own work. It’s not the same kind of mentality at all. From the editorial perspective, a lot of an editor’s function, which most people don’t think about, is not actually grammatically reshaping a text. Most editors are not making line edits on every single line you write. It’s more managerial—figuring out reviews, galley copies, cover copy, and that kind of work. In a big company that is spread out with a publicity department, a marketing department, and an art director.

With my own tiny press, I am everything. I’m the art director, I am the person who is figuring out the copy and who’s ultimately responsible for the quality control of whatever I put out. I had to learn a little bit about every single function that there is in a large company and understand how the publishing industry works. I had to know everything from terminology to how book sales work, how royalties are calculated.

I think I have a good understanding of the industry. I’ve never actually worked in a big publishing house, but I’ve talked with enough people and asked enough questions that I have an idea of how certain things happen.

You have written novels set in so many different sub-genres: magical realism, noir with vampires, near-future sci-fi, and your recent bestseller with these awesome supernatural elements. What draws you to write speculative fiction?

I would actually say that my recent crime novels have no speculative elements. Untamed Shore and Velvet Was the Night are completely realistic. There’s nothing supernatural about them. I did write a noir called Certain Dark Things, which does have vampires in it. I like all kinds of things that exist in different kinds of categories. What I don’t like is the tendency for Anglo literature to restrain itself to a single space.

I think in Latin America, when I was growing up, there wasn’t that feeling, “Oh, is it crime novel? A ghost shows up, so then it’s not really crime, now it’s supernatural.” I think nobody really cares in Latin America if it’s a crime novel and a ghost shows up.

For Anglo-Saxon culture that would be “Oh no, you have just crossed streams you’re not supposed to cross, and everything is supposed to be just one thing.” I’m just like to let it be whatever it wants to be. I understand things have to be put on shelves for display and for selling, but this kind of innate desire to keep a genre pure—what is that about? I like to bounce between genres and I don’t think boundaries are really that important. Or as important as they were maybe to a previous generation.

As a writer, do you set out with an idea in mind? Or do you let the story go where you think it naturally needs to go?

I don’t worry so much about what category it’s going to be in until it’s done. With Mexican Gothic, I knew it had to be a gothic novel, because that’s what I wanted to do. Gothic is a specific kind of genre, but it’s also a liminal genre, it has many other elements within its belly.

If you look at a story like Frankenstein, would you say it is a science-fiction story, a horror story, a gothic story, or a literary classic story? If it was up to me, I would tell you it’s all of those things.

With Mexican Gothic, it’s definitely a gothic novel. It has all the elements that I thought should go into a gothic novel, but in the end the answer to what’s going on is kind of science fictional. When I was done with it, I didn’t say okay, this is science fiction, so now I have to scrape it off and put a ghost in there. There is a science fiction element; it’s not the overwhelming element, but it doesn’t matter in the end.

Frankly, it becomes really strange when people demand a purity of literature that has existed so little in the history of literature.

What does it feel like to have a book you’ve created that everyone in the world seems to be talking about? Does it feel surreal, or does it feel like, “Of course I’ve always been brilliant, I’m glad you noticed?”

It’s nice, its good. On a practical level it was a lot easier to renegotiate my contract than ever before. I have not had the easiest time selling and suddenly it was a much smoother and simpler process. The biggest difference is it’s easier to get attention externally from review sites and magazines. It’s also sort of easier to get certain kinds of support from my publishing company on a day-to-day basis.

The good thing about being a writer is that you’re a little bit anonymous, so nobody really knows me around Vancouver except for the people in my co-op where I live. I am kind of like the celebrity of that little enclave. In the wider world, I can just operate as myself.

I do worry that it might box me in if people think I only do horror, but my next novel is crime so I’m staying true to my desire to switch genres every single book.

We have the first chapter of Velvet Was the Night following this interview. Can you tell us a little bit about that book?

It is set in 1971 in Mexico City. It follows a hired thug and a kleptomaniac secretary who are both on the trail of a missing woman and it’s set against the background of real-life unrest in Mexico City when the government was killing and suppressing activists in Mexico, especially student activists during that time period. It opens with this demonstration where a bunch of people are attacked. It’s a dual point of view story.

How have all of the places you’ve lived affected the way you write creatively? Why do you keep going back to Mexico as the setting for your new works?

At one point I was thinking “Am I writing too much about Mexico?” Then I thought it’s not like we’re over-saturated with stories set in Mexico. I go back because there’s still stuff to be told and angles I haven’t explored.

I haven’t been able to write what I call my New England story, which is inspired by my college in New England. I also haven’t written my Vancouver story, which is inspired by my time there. I’m getting old enough that the 1990s for college and the early 2000s here in Canada will be historical.

I’m probably just waiting so that I can put them under that label and seem like I was very smart and did a lot of research when I was just remembering stuff that I did.

If you could go back and whisper advice in your ear when you published that first story in Shimmer, what would it be?

I guess at one point I was worried about not having an MFA and not having the credentials. I kind of got over it because I couldn’t afford one. I would say, “Yeah, it doesn’t really matter at all. Just chill. It will solve itself. At one point, they will be teaching you.”

Wild hypothetical: it is 150 years in the future and there is an MFA classroom in which they are devouring your work voraciously. What do you hope you’re known as? What do you hope is your literary legacy that people will learn and grow from?

I hope that I’m known as the writer that showed people that Latin American writers can write something aside from magic realism and suffering porn.

“It is well established that the Hawks are an officially financed, organized, trained and armed repressive group, the main purpose of which since its founding in September 1968 has been the control of leftist and anti-government students.”

—USA Department of State, confidential telegram, June 1971

June 10, 1971

Chapter 1

He didn’t like beating people.

El Elvis realized this was ironic considering his line of work. Imagine that: a thug who wanted to hold his punches. Then again, life is full of such ironies. Consider Richie Valens, who was afraid of flying and died the first time he set foot on an airplane. Damn, shame that and the other dudes who died, Buddy Holly and “The Big Bopper” Richardson; they weren’t half-bad either. Or, there was that playwright Aeschylus. He was afraid of being killed inside his house and then he steps outside and wham, an eagle tosses a turtle at him, cracking his head open. Murdered, right there in the most stupid way possible.

Often life doesn’t make sense and if Elvis had a motto it was that: life’s a mess. That’s probably why he loved music and factoids. They helped him construct a more organized world. When he wasn’t listening to his records, he was pouring over the dictionary, trying to memorize a new word, or plowing through one of those almanacs full of stats.

No, sir. Elvis wasn’t like some of the perverts he worked with, who got excited smashing a dude’s kidneys. He would have been happy solving crosswords and sipping coffee like their boss, El Mago, and maybe one day he would be an accomplished man of that sort but for now there was work to be done and this time Elvis was actually eager to beat a few motherfuckers up.

He hadn’t developed a sudden taste for blood and cracking bones, no, but El Güero had been at him again.

El Güero was a policeman before he joined up with Elvis’s group and that made him cocky, made him want to throw his weight around. In practice, being a poli meant shit because El Mago was the egalitarian sort, who didn’t care where his recruits came from—ex-cops, ex-military, porros, and juvenile delinquents were welcome as long as they were young and worked right. But the thing was El Güero was twenty-five and he was getting long in the tooth, and that was making him anxious. Soon enough he’d have to move on.

The chief requirement of a Hawk was he needed to look like a student so he could inform on the activities of the annoying reds infesting the universities—Trotskos, Maoists, moscovites, there were so many flavors of dissidents, Elvis could barely keep track of all their names and organizations—and also, if necessary, fuck up a few of them. Sure, there were important fossils, like El Fish, who was twenty-seven. But El Fish had been in one political shenanigan or another since he was a wee first-year Chemistry student; he was as professional as porros got. El Güero was twenty-five and he hadn’t achieved nearly as much and he was anxious. Elvis had just turned twenty-one and El Güero felt the weight of his age and eyed the younger man with distrust, suspecting El Mago was going to pick El Elvis for a plum position.

Lately, El Güero had been making snide remarks about how Elvis was a marshmallow, how he never went on any of the heavy assignments, and instead he was picking locks and taking pictures. Elvis did what El Mago asked and if El Mago wanted him to pick the locks and snap photos, who was Elvis to protest? But that didn’t sway El Güero, who had taken to impugning Elvis’s masculinity in veiled and irritating ways.

“A man who spends so much time running a comb through his hair isn’t a man at all,” El Güero would say. “The real Elvis Presley is a hip-shaking girlie-man.”

“What you getting at?” Elvis asked and El Güero smiled. “What you saying ’bout me now?”

“Didn’t mean you, of course.”

“Who’d you mean, then?”

“Presley, like I said. The fucking weirdo you like so much.”

“Presley’s the King. Ain’t nothin’ wrong in liking him.”

“Yankee garbage,” El Güero said smugly.

And then, when it wasn’t that, El Güero decided to use an assortment of nicknames to refer to Elvis, none of which were his code name. He had a fondness for calling him La Cucaracha, but also Tribilín, on account of his teeth.

In short, Elvis was in dire need of asserting himself, of showing his teammates that he wasn’t no fucking marshmallow. He wanted to get dirty, to put all those fighting techniques El Mago made them learn to good use, to show he was as capable as any of the other guys, especially as capable as El Güero who looked like a fucking extra in a Nazi movie and Elvis had no doubts that his dear papa had been saying “heil” real merrily until he boarded a boat and moved his stupid family to Mexico. Yeah, El Güero looked like a Nazi and not any Nazi but a fucking gigantic, beefy motherfucking Nazi and that’s probably why he was so pissed off, because when you look like blond Frankenstein, it’s not that easy to blend in with no one and it’s much better to be a shorter, slimmer little dark-haired fucker like Elvis. That’s why El Mago kept El Güero for kidney-smashing and he left the lock picking, the infiltrating, the tailing, to Elvis or El Gazpacho.

El Gazpacho was a guy who’d come from Spain when he was six and still spoke with a little bit of an accent, and it goes to show that you can be all European and pretty much fine because that dude was as nice as could be, while El Güero was a sadist and a bully with an inferiority complex a mile wide.

Fucking son of an Irma Grese and a Heinrich Himmler! Fucker.

But facts were facts and Elvis, only two years with this group, knew that as the most junior of the lot he had to assert himself somehow or risk being sidelined. One thing was clear: there was no fucking way he was headed back to Tepito.

Therefore, it’s no surprise that Elvis was a bit nervous. They’d gone over the plan and the instructions were clear: his little unit was to focus on snatching cameras from journalists who would be covering the demonstration. Elvis wasn’t sure how many Hawks would be coming in and he wasn’t quite sure what the other units would be doing and really it wasn’t like he was supposed to ask questions, but he figured this was a big deal.

Students were heading towards El Monumento a la Revolución, chanting slogans and holding up signs. From the apartment where Elvis and his group were sitting, they could see them streaming towards them. It was a holy day, the feast of Corpus Christi, and he wondered if he shouldn’t go get communion after his work was over. He was a lapsed Catholic, but sometimes he had bouts of piousness.

Elvis smoked a cigarette and checked his watch. It was still early, not even five o’clock. He went over the word of the day. He did that to keep his mind sharp. They’d kicked him out of school when he was thirteen, but Elvis hadn’t lost his appreciation for certain types of learning, his finger sliding down the pages of the Illustrated Larousse.

The word of the day was “gladius.” He’d picked it because it was fitting. After all, the Hawks were organized in groups of one hundred and they called the leaders of those groups “the centurions.” But there were smaller units. More specialized subgroups. Elvis belonged to one of those; a little goon squad of a dozen men headed by El Mago, further subdivided into three smaller groups with four men each.

Gladius, then. A little sword. Elvis wished he had a sword. Guns seemed less impressive now, even if he’d felt like a cowboy back when he first held one. He tried to picture himself as one of those samurais in the movies, swinging their katanas. Now wasn’t that something!

Elvis hadn’t known anything about katanas until he joined the Hawks and met El Gazpacho. El Gazpacho was all over the Japanese stuff. He introduced Elvis to Zatoichi, a superfighter who looked like a harmless blind man but who could defeat dozens of enemies with his expert moves. Elvis thought maybe he was a bit like Zatoichi because he wasn’t quite what he appeared to be and also because Zatoichi had spent some time hanging out with the yakuza, who were these crazy dangerous Japanese criminals.

Gladius. Elvis mouthed the word.

“What’re you learning today?” El Gazpacho asked. He had his binoculars around his neck and he was wedged by an open window and he didn’t look nervous at all.

“Roman shit. Hey, you know any decent flicks with Romans?”

“Spartacus is pretty okay. The director filmed 2001: A Space Odyssey. It’s cool, takes place aboard a spaceship. Also sprach Zarathustra.”

Elvis had no idea what El Gazpacho had said, but he nodded and held out his cigarette. El Gazpacho grinned and took a drag before returning it to him. El Gazpacho grabbed his binoculars and looked out the window, then he checked his watch.

The students were singing the Mexican anthem and The Antelope was mocking them by singing it with them. In a corner, El Güero looked bored as he cleaned his teeth with a toothpick. The others—members of their sister unit, another little group of four—looked tense. Tito Farolito in particular had resorted to telling bad jokes to lighten up because the word was it was ten thousand protesters and that was no small amount. Ten thousand is the kind of number that makes a man think twice about this whole line of work, even if he’s drawing one hundred pesos a day and twice as much if he’s with El Mago. Again, Elvis wondered how many Hawks would be at the demonstration.

The Hawks began to stream into the rally, carrying signs with the face of Che Guevara plastered on them and chanting slogans like “Freedom for the political prisoners!” It was a ruse, a way to allow them to get close to the protesters.

It worked.

Just when the students were walking in front of The Cosmos movie theater, there came the first shots. It was time to rock and roll. Elvis put out his cigarette. His unit hurried down the stairs and exited the apartment building.

Some of the Hawks carried kendo sticks, others shot into the air, hoping to scare the students that way, but Elvis used his fists. El Mago had been clear about the basics: grab any journalists, take their cameras, rough them up if they got stubborn. People with cameras and journalists only. They weren’t to waste their time and energy beating any random nobody who didn’t have no film with him. No killing, either, though they could rough ’em up nicely.

Elvis had to give it to the protesters because in the beginning, when the fighting started, they weren’t doing half bad, but then the shooting was no longer bullets in the air and the students began to panic, began to lose it, and the Hawks were prepared, streaming in from different sides.

“It’s blanks!” a young man yelled. “It’s not real bullets, it’s just blanks. Don’t run away, comrades!”

Elvis shook his head, wondering what kind of stupid dumbfuck you had to be to think those were blanks. Did they assume this was an episode of Bonanza? That a sheriff with a tin star pinned to his vest was going to ride in before commercials and it would be fine?

Others were clearly not as optimistic as that guy urging everyone to stay put. Doors and windows were slamming closed along the avenue and the nearby streets, and shopkeepers pulled down their rolling steel shutters.

Meanwhile, the granaderos and the cops were sitting pretty. There were plenty of men with thick anti-bullet vests and heavy helmets on their heads and shields in their hands, but they were forming a sort of perimeter around the area and none of them intervened in one way or the other.

Elvis grabbed a journalist who had an ID clipped to his vest and when the journalist squirmed and tried to hold on to his camera, Elvis told him if he didn’t let go he was going to break his teeth and the journalist relented. He could see El Güero wasn’t being so polite. El Güero had another photographer on the ground and he was kicking him in the ribs.

Tough shit, Elvis thought, and he exposed the film of the camera he’d grabbed and then tossed the camera away.

People with cameras were easy to spot, but El Mago had also told them to give all journalists in general a scare, not only the photographers—’cause all journalists could use a lesson about who was boss, these days—and it was a bit harder to figure out who the print and radio journalists were. But The Antelope knew all their faces and names and he pointed them out when he saw them; that was his role. The other thing to keep in mind was that they couldn’t let themselves be photographed, so Elvis spent half his time trying to spot cameras, trying to watch out for a flash, lest some eager little fucker get a good picture of him.

Nevertheless, it was all going pretty much as expected until the sound of a machine gun blasted the air and Elvis turned to look around.

What the fuck? Bullets were one thing, but were the Hawks now shooting with machine guns? Was it even their own people? Maybe a clever student had brought firepower. Elvis raised his head and looked at the rooftops, at the apartment buildings, trying to figure out where the hail of bullets was coming from. It was hard to tell, with all the people running to and fro, and the screaming, and someone on a loudspeaker saying that people should retire to their homes. Retire to your homes, now!

The ambulances were coming, he could hear them wailing, heading down Amado Nervo. They were pressing forward and the machine gun had ceased, but bullets were still flying and Elvis hoped no trigger-happy idiot hit the wrong target. All the Hawks had their hair cut short and they wore white shirts and sneakers to help identify them, but Elvis’s group also sported denim jackets and red bandanas because they were part of one of the elite teams; because this was the dress code for El Mago’s boys.

“Grab that son of a bitch,” El Gazpacho said, pointing to a dude who held a tape recorder in his hands.

“Got it,” Elvis said.

The dude looked old, but he was surprisingly nimble and managed to run a few blocks before Elvis caught up with him. He was screaming outside the back door of an apartment building, begging to be let in, when Elvis yanked him back and told him to hand over his cassette recorder. The man looked down at his hands as though he didn’t remember he had been lugging that around and maybe he didn’t. Elvis took the recorder.

“Get lost,” he ordered the man.

Elvis turned around, ready to go find his teammates, when El Gazpacho stumbled into the side street where Elvis was standing. Blood dripped down his chin and he stared at Elvis and raised his arms in the air and he tried to speak, but the only sound was the bubbling of blood.

Elvis rushed forward and caught him before he tripped and fell. A minute later, El Güero and The Antelope rounded the corner.

“What the fuck happened?” Elvis asked.

“No idea,” The Antelope said. “Maybe one of those students, maybe—”

“We gotta drive him to the doctor.”

“Fuck no,” El Güero said, shaking his head. “You know the rules: we wait until one of the cars swings by and then we load him into that. No driving him ourselves. We still have work to do. There’s a cameraman from NBC hiding in a taco shop and we’ve got to grab that prick.”

El Gazpacho was gurgling like a baby, spitting more blood. Elvis tried to prop him up and glared at his teammates. “Fuck that, help me get him to the car.”

“The car’s too far. Wait for an ambulance or one of the vans to swing by.”

Yeah, yeah. But the problem was Elvis didn’t see no ambulance or no van swinging by right then and everyone was busy as fuck. It could take nothing for El Gazpacho to be rolled into a vehicle or it could take a while.

“Motherfucker, it’ll be five minutes and then you can go figure out what’s up with the cameraman.”

El Güero and The Antelope didn’t look very convinced and Elvis couldn’t hold poor Gazpacho forever and he couldn’t carry him nowhere. He wasn’t that strong, he was quick and wily and could kick and punch courtesy of the personal defense lessons El Mago gave them. The strong one, that was El Güero, a fucking Samson who could probably lift an elephant in his arms.

“El Mago ain’t going to be happy if his right-hand man bites the dust,” Elvis said and at last that seemed to rattle The Antelope enough, because The Antelope was deadly afraid of El Mago and El Güero was a subservient snake when El Mago was around, sliding on his belly for crumbs, and some preservation instinct must have activated inside his dull brain.

“Let’s get him to the car,” El Güero said and he lifted El Gazpacho, who was no small man, as though he was a baby, and they ran the few blocks necessary to reach the alleyway to find that someone had torched their car.

“Who the fuck!” yelled Elvis, and he spun around, furious. He couldn’t believe it! Those little fuckers! It must have been one of the protesters who’d singled out the vehicle due to its lack of plates.

“Well, your plan’s fucked now,” El Güero told him and the sadistic motherfucker looked a bit giddy, and Elvis didn’t know if it was because things weren’t going well for Elvis or because he hated El Gazpacho.

Elvis looked around at the lonely alleyway strewn with garbage. The smoke made his eyes water and the scent of gunpowder clogged his nostrils. He pointed to the other end of the alleyway.

“Come on,” he said.

“I’m heading back. We got work to do,” El Güero said and he was putting El Gazpacho down. Just dumping him down on the ground like a sack of flour, leaving him there atop a damn pile of rotten lettuce. “We gotta get that cameraman.”

“Don’t you fucking dare, you son of a bitch,” Elvis said. “El Mago, he’ll have your balls if you don’t help us.”

“Up your ass. He’ll be pissed we were a bunch of pussies and didn’t finish the job. If you want to play nurse, do it alone.”

That was that. El Güero was walking away and The Antelope didn’t seem to have made up his mind about what to do. Elvis couldn’t believe this crap. He wasn’t no softie, but you didn’t leave one of your teammates to bleed out in a stinking alleyway like that. It wasn’t right. And this was El Gazpacho! Elvis would rather have a foot amputated than leave El Gazpacho behind.

“Come on, help me here. What? You lost your dick?” Elvis asked.

“What the fuck’s my dick—”

“Only a limp, dickless shit would be standing there rubbing his hands. Grab him by the shoulders.”

The Antelope grunted and complained, but he obeyed. The three of them made it to the end of the alleyway and down the street. There was a blue Volkswagen parked there and Elvis shattered the glass of the passenger’s seat with a bottle which he found on the ground. He slid into the car.

“What you gonna do?” The Antelope asked.

“What’s it look like?” Elvis replied as he frantically looked inside his backpack until he fished out the screwdriver. Handy thing, that. It was an old habit of his to carry it from back in the day when he’d been a juvenile delinquent. The cops would give you a massive beating if they found you carrying a knife and then arrest you for having concealed weapons, but a screwdriver was no knife. The other thing he liked to carry were two little pieces of metal that he used to pick locks when he didn’t have his full kit.

“You can’t hot-wire it like that,” The Antelope said, but The Antelope liked to complain about everything.

Elvis jammed the screwdriver in place, but it wouldn’t go. He bit his lip, trying to calm the fuck down. You can’t pick a lock if you’re shivering, same with starting a car. Gladius.

“Man, can’t you hurry it?”

Gladius, gladius, gladius. Finally! He got the motor running and motioned for The Antelope to get in the car and The Antelope started protesting.

“The mission still needs to be completed and what about El Güero and the others and that cameraman from the American network?” he asked, sounding a little breathless.

“Jump in,” Elvis ordered. He couldn’t afford to have a panicked operative and he kept his voice level.

“We can’t take off.”

“He’s gonna bleed to death if you don’t press against his wound,” Elvis continued in that same level tone he’d learnt from El Mago. “You gotta get in the car and press hard.”

The Antelope relented and pushed El Gazpacho into the car and climbed in next to him. Elvis took off his denim jacket and handed it to The Antelope. “Use that.”

“I think he’s gonna die anyway,” The Antelope said, but fortunately he did press the jacket against El Gazpacho’s chest as instructed.

Elvis’s hands were slick with El Gazpacho’s blood as he took the steering wheel. The gunshots had started again.