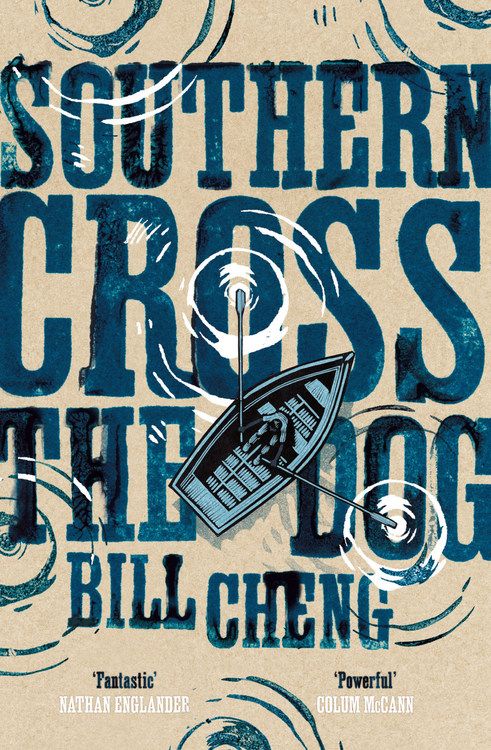

Eroding Lives: an Interview with Bill Cheng

A great flood opens Bill Cheng’s debut novel, Southern Cross the Dog. Torrents of water ravage the landscape, sweeping homes, families, and livelihoods away in seconds. But the waves cut deeper. Like the land beneath his feet, eight-year-old Robert Chatham’s childhood is eroded away, reshaped into something both more magnificent and horrible than he could imagine.

From the flood-ravaged world of 1927 Mississippi, Cheng follows Robert through a life that cannot escape tragedy. Traveling through brothels, swamplands, prisons, and backwater trapper camps, Robert realizes that being a young black man in the south is the least of his hardships. As the reader is told by blues musician, Elli Cutter, Robert is “bad crossed,” tied to a demon that haunts him with misfortune. With no way to rid himself of the jinx, Robert must instead bind himself to it.

Mississippi too, it seems, has its own demons. Both Robert and the land will be set aflame, torn to pieces, washed away, rebuilt and destroyed again and again. However, beneath these torrents of misfortune, lives are transformed, the erosion carving their stories into something truly exceptional.

It is without hesitation that Tethered by Letters recommends Cheng’s novel. Southern Cross the Dog is not a book for lazy readers. Written with startlingly intricate and delicate prose, to read this novel is to experience it: to feel the pain of being “bad crossed,” the loss of lives reshaped by a flood of prose. Like the best literature, Cheng’s novel will pull you in, inch by inch, page by page, until you’re suddenly drowning. It will not let you come up for air until that very last sentence. This, dear readers, is a book that will stay with you.

Cheng on Southern Cross the Dog

When I sat down to talk with Bill Cheng, I first asked about his inspiration for the book. Although I expected an answer about his interest in the racism of the 1920’s, Cheng smiled and told me: “I’ve always loved the blues.” Asking him to elaborate, he told me how he’d been listening to the blues since he was seventeen, and how he’d always been interested in the time period when this musical genre came to life. “When I got to grad school and I started working on the novel I knew that I had to 1) write about something that was personally important to me, and 2) write something that would sustain my interest over the next few years.” Because the blues were very central to Mississippi in the early-to-mid 20th Century, it was the natural setting for Southern Cross the Dog.

The blues were also his inspiration for Robert’s character. Although not tied to the music—as supporting character Elli Cutter is—Robert is “what every blues singer sings about. He’s the person where the forces around him conspire against him.” As the story progresses, we see Robert’s life stripped away by the demons that haunt him, forced to reinvent himself to survive.

Surprisingly, few of his misfortunes stem from his race. In fact, the themes of racism in the novel are subtle, simmering on the periphery of the main story. When I asked Cheng how he achieved this impressive balance, he laughed. “In part it was willful ignorance,” he explained, “I didn’t think about the book in terms of race when I wrote it. My deconstruction of what it would be like to be Robert Chatham didn’t involve that much race aversion…It was about this larger thing about the structures of our world and what it’s like to have that fall apart around us that was my central focus. That was more important to me.”

Cheng on Writing

One of the most interesting things about Southern Cross the Dog is the structure. Vaulting between time periods (1927 to 1932, back to 1927, forward to 1941) and narratives (two side characters are given their own first-person stories), Cheng allows the novel to expose Robert’s life at from every angle.

“The book isn’t exactly causal,” Cheng explained, which allowed him to employ this temporal structure. With each jump, he was very conscious of how each new view would enhance the reading experience. “I asked myself how I could juxtapose these sections so something would resonate from them.” Cheng had seen other stories written like this, and found the sections “both jarring and discordant, but they were also really fascinating.” These jumps also allowed Cheng to cover a very wide time range without being bogged down by narrative transitions. “You feel like there is a kind of energy to it.”

This structure also allowed Cheng to “let air into the novel.” “You can over plot a thing,” he explained, “where the book becomes a slave to itself. I didn’t want that.” Because his favorite fiction “opens up in unexpected ways,” he strove to let Southern Cross the Dog have the space it needed to come into its own.

Of course, this meant that there were several sections of the novel that didn’t make it into the final draft. In fact, at one point, secondary characters were gaining so much power that Cheng had to reevaluate the novel, asking himself who the book was really about:

“It was honestly getting out of control,” Cheng confessed, “I was getting so far away from the idea of what a novel should look like. I realized that I needed to reinforce—in my writing and in the reader’s mind—that this book was about Robert and the path he has to go through. I would like to say that it was one of those magical moments where the characters tell you where the story is going, but it wasn’t.” Cheng laughed, shaking his head. “Honestly, sincerely, I had to go back in and say, ‘you, you do this and this. You do it interestingly and I’ll write it down.’”

By allowing the plot to open up, Cheng also opened his language up to new possibilities. Although previously drawn to laconic, punchy prose, Cheng chose to use a “meatier” style for Southern Cross the Dog. “I wanted the writing to be both physically evocative and have a kind of gristle to it. It’s like chewing a tough steak…It has to make the reader feel like they’ve been through something.”

When I asked what drew him to this sort of style, he told me about reading Peter Matthiessen’s Shadow Country. “It’s over 1,000 pages,” he explained, “and it’s basically three novels slammed together about the development of the everglades and at the end of it, I was exhausted. I was physically exhausted and I thought: ‘what a wonderful thing. Here I am, just scanning my eyes across the page, and the end, something has happened such that I feel completely tapped out.’ I definitely wanted that from my book, to be able to evoke that kind of feeling.” To create this experience, Cheng constructed an intricate story—in both the prose and the plot—so by the time the reader reached the last page, he too would feel like he’d been through something substantial.

Cheng on Publishing

Cheng began writing Southern Cross the Dog in 2008 at Hunter College. “I had the opportunity to work with Colum McCann in grad school. On the first day of class he said, ‘While you are here, for the next few years, you will be working on a novel.’ Which is an insane thing to say to a group of kids who have never worked on a novel before.” As McCann instructed, Cheng began his novel, inspired by the impossible ambitions of his professor.

Four years later, he’d completed Southern Cross the Dog. Because of the excellent connections he made at Hunter College, Cheng didn’t have to undergo the usually arduous process of querying for his novel. “In a lot of ways, I was really lucky. I had great people backing me so I didn’t have to work as hard as some of my friends did in terms of shopping things around.” After he finished, one of his professors passed the novel to his agent, and she loved it. Soon after, she landed him a great deal with Harper Collins.

Although his professors were an invaluable resource, Cheng also spoke of how grateful he was for his fellow students. “I love the Hunter College program. We’ve been out for three years now and I still talk to 80% of my class all the time. They’re my first readers. Whenever I have some weird existential crisis I call them and we go off and talk…it’s wonderful.” In fact, Tethered Tidings’ author Jessica Soffer was one of Cheng’s classmates.

Although Cheng stressed the importance of having great writing friends, he had several other strong points about how to be a better writer. For example, referencing Colum McCann’s mentoring, Cheng advises new writers to be “incredibly ambitious” and to remember “every problem has a solution.”

For novice writers, Cheng said that one should keep in mind that “the most interesting writing is the writing that does two or more things at the same time.” For more practiced writers, Cheng advised that “your writing should be personally important all the time. If you are doing something because it’s expected or it’s what others have told you it’s what literature should look like, let someone else do that. You should be doing something that is unique and special to you.”

Excerpt from Southern Cross the Dog

In the rain the men crowded the river edge. They’d worked through the night, sandbags at their shoulders, the numbness set heavy in their chest and arm. They sunk waist deep into the soft mud, hafting their bodies forward and up. When the lantern went, they stopped in their places and listened to each other breathe. Rain flickered white in the darkness. Somewhere beyond them was the river. It groaned and roiled, eating the banks, crisping against the rocks. After a moment, someone cut the wet from the wick and relit the lantern.

The men shifted under a cake of rain and mud and sweat. Come dawn a wound of light belied through the clouds. In the light, they could see what they couldn’t before. Piece by piece, the embankment was falling away into the current, their sandbags shooting up downriver.

There was a pop, and a jet of gray water gushed through the embankment. Shouts rose up and a wave of men raced toward the break. They shored it up with their bodies, crying more men, more men. The air cracked and the ground trembled. The water ripped through them like paper, sending them into the air, into the mud. The river burst forward and the levee crumbled under it, tearing through the camp through forest, rising up in a great yellow wall, driving close, fast, screaming like a train, its roar sucking up the sky, a voice crowning open like the Almighty, through Filter and Cary and Nitta Yuma, acre by acre, through cornfields and cotton rows; through plantation houses and dogtrots, wood and brick and mortar, through the depots and churches and rail yards, through forest and valley, snapping boulders through the air. Houses rose up, bobbed, then smashed together like eggshells. Homes bled out their insides—bureaus, bathtubs, drawers, gramophones—before folding into themselves. The people scrambled up on their roofs, up tress, clinging to one another. The water blew them for their perches, swept them into the drift, smashed them against the debris. They bubbled up swollen and drowned, rag-dolling in the current, moving deeper and deeper inland, toward Issaquena.