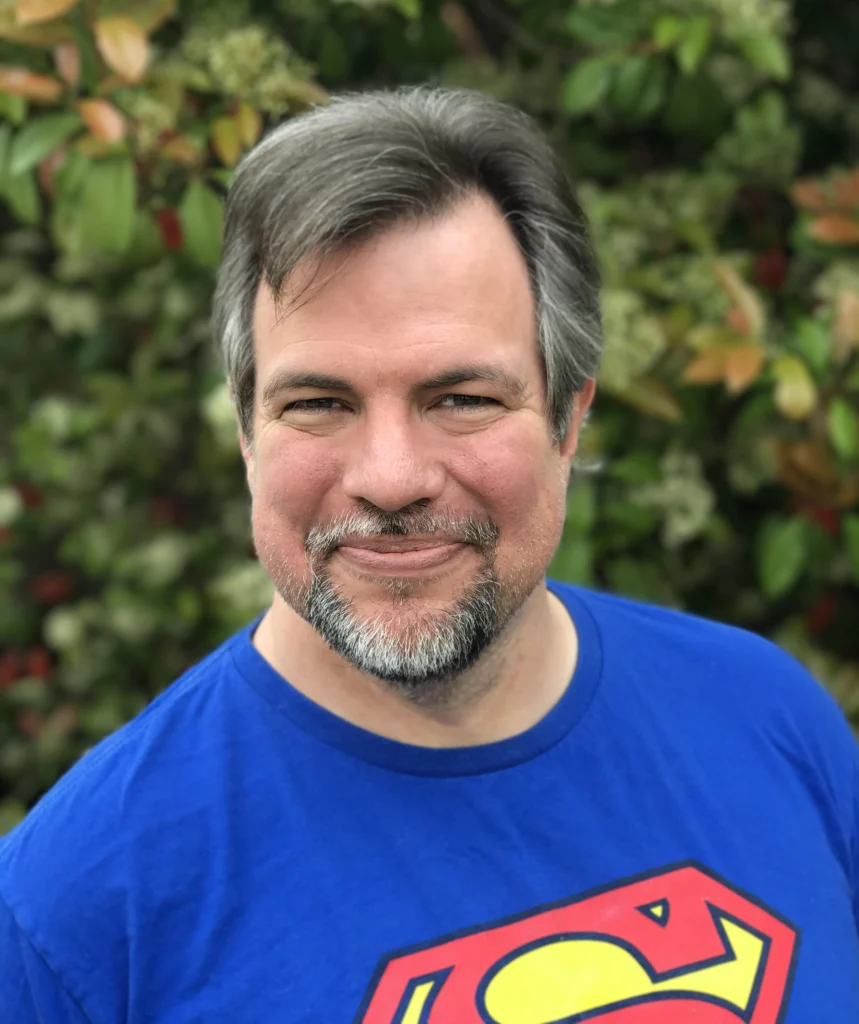

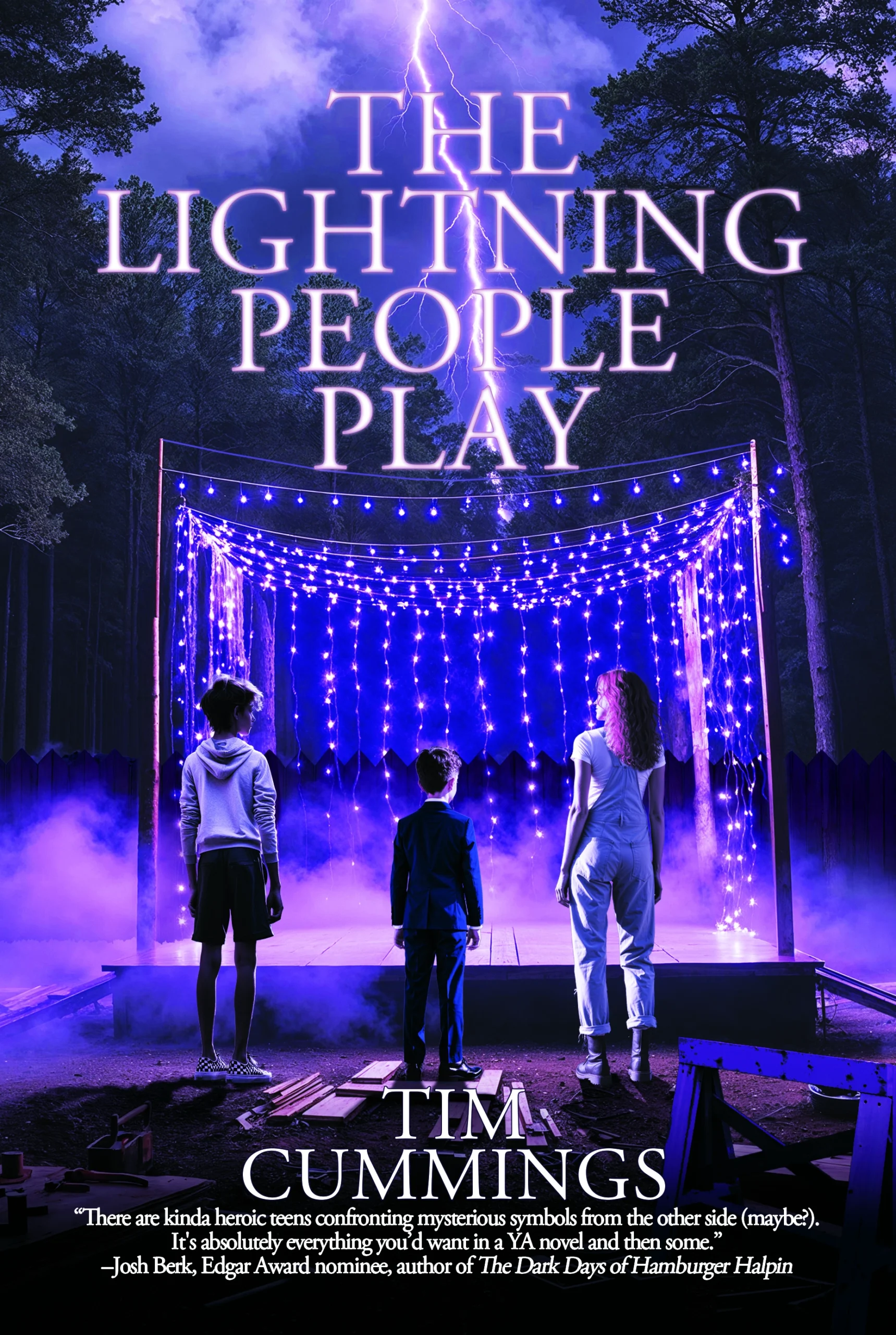

An Interview with Tim Cummings

Both of your novels feature specific communities that often carry a bad rap. What draws you to explore misunderstood people like the Goths and theater kids?

I am both of those. I have been since adolescence. So, they’re worth exploring and spending time with because I can bring truth and clarity to goths and theatre kids. How awesome.

In addition to exploring the world of theater kids, The Lightning People Play features a character who has epilepsy. Why this diagnosis for Baxter? How did you ensure you were representing the realities of this illness accurately?

Well, I lived it. My brother Matthew had grand mal seizures his entire life. Sadly, we lost him in the summer of 1997 when he was twenty-six due to complications from a grand mal seizure.

We shared a room when I was a kid, and he used to have tremendous seizures in the middle of the night. I always felt there was some hidden magic happening in that room, a door to another world, whether that was some kind of preventative trauma response, or my subconscious at play, or something else.

Ancient Greeks believed epilepsy was a “sacred disease,” and correlated it with the divine. Some Meso-American cultures believe epilepsy comes from a struggle with the afflicted person’s animal soul following a battle between the naguales or spirits who serve the forces of Good and Evil. So, there is a lot of magical thinking around it, and as witness to it for so many years, I understand that and I have felt that.

This book allowed me to transpose those memories into something mystical and beautiful by utilizing my involvement in theatre for over forty years as a framework to tell a story about the two young brothers, Kirby and Baxter; about creative collaboration among friends; and an important story about a struggling family that figures out how to deal with the affliction.

There are many ways a person can be afflicted with, and manage, epilepsy. This book explores ways that fit this particular family at this particular time in this particular set of circumstances. But it’s going to be different for everyone. The seizure scenes in this book, though drawn from real life, are also not going to look like other epileptics’ seizures. And they’re on a journey to figure it out, with mistakes made along the way, which is how it really was for my family, and is for this one.

Baxter’s older brother, Kirby, is determined to raise money so they can get Baxter a seizure-alert service dog and decides to put together a play with his closest friends. You have an extensive theater background. How did that influence the way you approached writing the theater-related elements of the novel?

Theatre means a lot to me. I’ve been doing it since I was eleven years old. It helped me. I was a bullied kid, assaulted and harassed for being gay. Well, I mean, back then I was not “out,” obviously, because I was a child and didn’t even know what that meant yet, or what was even going on inside me. But I was, for the people around me, “weird” and “effeminate” and “sensitive,” so they tortured me. We’re seeing the same thing happen now with trans kids.

Theatre empowered me. There was a teacher who intuited I had talent. I had no idea I did. Once I discovered it, that I had it in droves, I was off on my journey. The most satisfying thing about it back then was that it was a very rebellious act. It felt kind of punk rock, in hindsight. It angered and frustrated, annoyed and infuriated all the kids around me who had been bullying me and making my life really difficult. To see me on stage steeped in this power, this creativity and sense of play, really angered them. That made me feel so good. Theatre was a kind of f**ck you to the bullies. I loved so much that they hated it. (It changes later in life, of course. Once you enter the professional realm, it feels like a popularity contest.)

In the book, the kids have a theatre mentor named Thaddeus Krasinski. He runs the junior high and high school theater programs. He is a professional working actor and director. He sets the protagonist off on his journey. He’s a loving, supportive, idiosyncratic character and is a conglomerate of so many integral theatre teachers and mentors I encountered along the way. He also has an interesting theory about theatre and being an artist in society. That character in particular was a useful, layered, beautiful vessel for approaching the theatre-related elements of the novel.

At its core, the novel is a love letter to explore and celebrate creativity, neurodivergence, friendship, and family. Why were those elements so important for you to highlight in the novel?

I’ve always been creative, wildly and unpredictably so. And so have the bulk of the people around me in my life. It is a driving force, and as such, a great narrative partner. I wanted to explore it through the eyes of teenagers who are doing it for a specific reason: to help someone.

Neurodivergence and neurodiversity need more representation and exploration. Kirby manages a mild case of OCD (though he is not diagnosed) and the events of the book aid him in managing it better; Mara Gecco utilizes her own unique way of speaking and communicating; Bax, of course, is navigating his epilepsy. I experienced a lot of neurodivergence growing up, not only because of my brother but from being around so many artistic, talented, and creative people.

Friendship, yes. I’ve had the same two best friends since I was thirteen years old. And all through my life, as an actor and a writer, I’ve built community and found family through the closeness that results from doing plays, and from writing. Friendship is a huge part of Alice the Cat as well.

The family story in this book is one of acceptance. Not everything works out the way you want it to when it comes to parents and siblings. But you don’t have to lose the love.

Were there any novels, movies, or plays that influenced or inspired you while writing The Lighting People Play?

Energetically, probably Something Wicked This Way Comes by Ray Bradbury, A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle, and The First Rule of Punk by Celia C. Pérez. I don’t know of other stories that explore these themes specifically utilizing epilepsy and theatre as their framework.

I am a voracious reader and am always being inspired by books, but I’m also content with this one not having any obvious comps. Not everything needs to be exactly like everything else. Gasp. Oh my God, how controversial. But, I mean, I think it’s refreshing. Let it be new.

How did writing this novel compare to writing your (award-winning!) debut novel, Alice the Cat? Were there any lessons you learned?

Alice was a good book to cut my teeth on. I had a great time with it, though I never expected it to be published. I wrote it in grad school and it felt fecund and unhinged, fun and funny, and loud and weird. As much as I wanted to try to adhere to the industry’s dictates of kid lit (and boy are they stringent), I also didn’t want to adhere to any dictates at all. And I think the book reflects that in its subversive playfulness. Is it a perfect book? Nope. That is what I love about it. It left me so much room to grow. If books were perfect, would we need to release about several thousand of them a day? I try to stay focused on process. Process is better. Process is where you get to be the artist.

We’re lucky to have published your short story, I Am a Person, in our Resurrection issue! Has your writing and editing approach changed since then? If so, how?

Still so proud of that, thank you F(r)iction! I loved inhabiting her voice. The first whispers of that story first came to me back in 2003 when we went to war. Again. War is such a constant. We know its voice so well. It’s magnified and voluble. With I Am a Person, I wanted to amplify and explore a different voice, that of a woman whose husband was fighting during WWII and who seems to have disappeared. I wanted to draw attention to a different kind of violence, the quiet kind that comes from dealing with war back home, in the kitchen, as a single mother. A contrast to the brut, in-your-face male violence we see intensified on the battlefields via the media.

The experience working with F(r)iction on that story was wonderful, and palpable, because it was obvious to me that the team loved the story and wanted it to be amazing. So, editing it felt like a collaboration.

What advice would you give to aspiring writers looking to get into the publishing industry?

Publishing is bananas. Start small. You don’t need a deal with the Big 5. Let that come later. There are so many small indie traditional publishers out there who want to support writers. You don’t need an agent to get a deal from one of them (though it helps because an agent can handle the contract and ensure the writer is being protected; publishing contracts are bananas as well).

Focus on writing the best book you can—that is what you have control over. Write with people. Join writing groups. Take writing workshops. I run several private workshops a year and I love doing it. I also teach for UCLA’s Writers’ Program and I love that too. It builds community. You have good, smart, kind but discerning eyes on your work, and that’s important.

Know that you dare to make a difference when you put anything out into the world as an artist. Accept that you, and what you write, is not for everyone. Put it out there, and keep going. Become a conscientious literary citizen. Your voice is important, your story is important.

How can we find and support you? What’s next on the horizon for you?

Best way to support a writer is to read their stuff. If you love it, amplify it. Review it. Reach out to the author. Even if you don’t love it, chances are you know someone who might. So, tell them about it. Give a book a fighting chance.

I am on Instagram and I have a website. I do a lot of events, and appearances.

Next up is something way more seditious. A work of adult literary fiction about some very abnormal stuff that happened in New York City after I graduated from NYU. I found myself lost in the darkly glistering underworld of the NYC club scene that was immensely popular at the time, (mid 90s), the Club Kids, designer drugs, outrageous fashion, alternative identities and wonky monikers. All of it pre-internet (how WILD to think about that), all of it so uninhibited and unpredictable—and often nefarious—all of it forever lost to the history of a city that can never go back to that time. It’s an unexpected love story, really, but a cautionary tale about how artists can sometimes delve too deeply into their work and not find their way back out again. It explores the the cost of losing your soul to your art, and points toward ways to get it back.