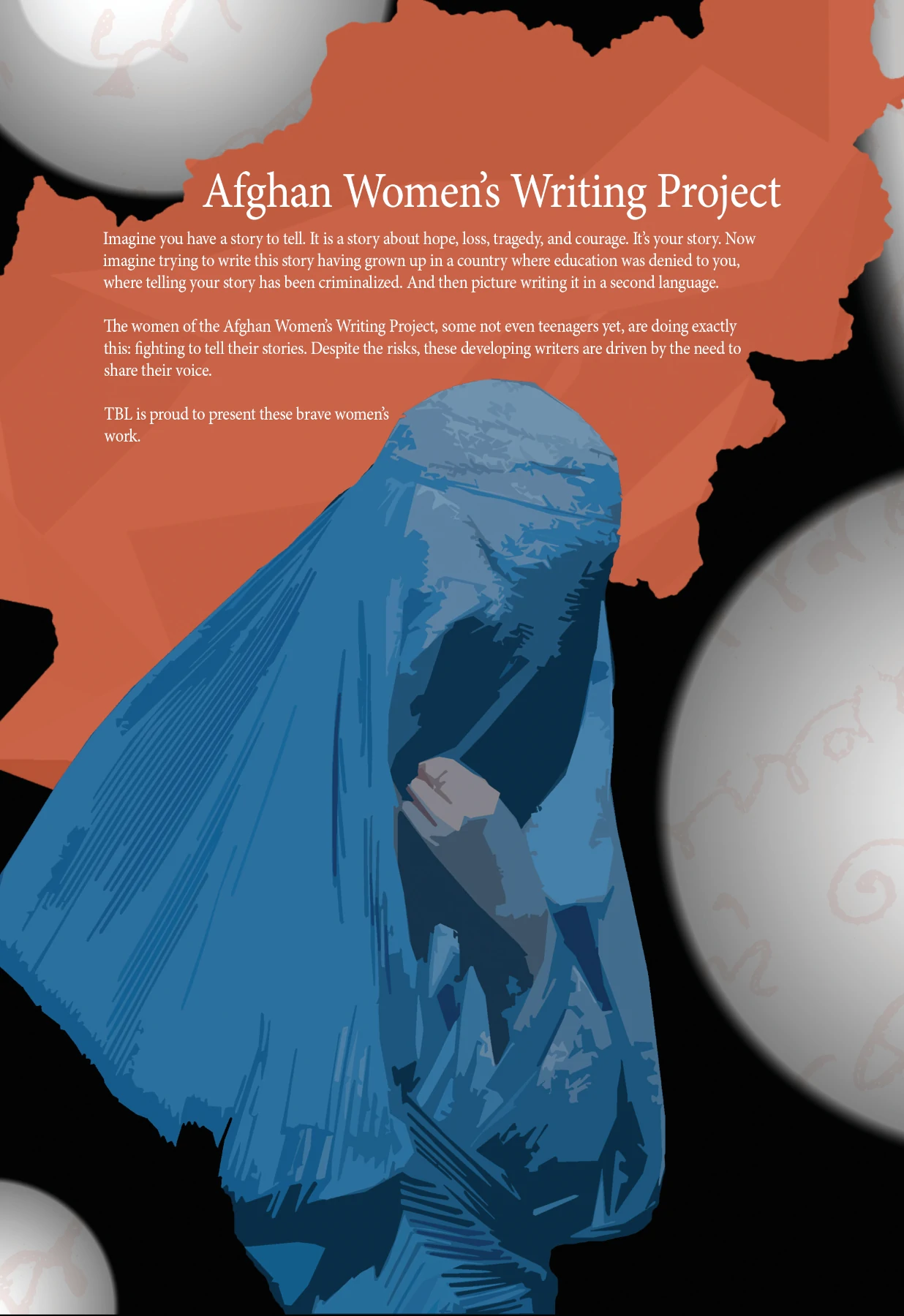

Afghan Women’s Writing Project

Words By Afghan Women's Writing Project, Art By Hugh Hartigan

Imagine you have a story to tell. It is a story about hopes, loss, tragedy, and courage. It’s your story. Now imagine trying to write this story having grown up in a country where education was denied to you, where telling your story has been criminalized. And then picture writing it in a second language.

The women of the Afghan Women’s Writing Project, some not even teenagers yet, are doing exactly this: fighting to tell their stories. Despite the risks, these developing writers are driven by the need to share their voice.

TBL is proud to present these brave women’s work.

I Am Sorry, My Sister

by Sayara

For Farkhunda, murdered on March 19, 2015 by a mob of men in Kabul, aged 27

Your words went unheard and you were punished for a sin you did not commit. I am sorry for the wild behavior of your cruel brothers. Farkhunda, my poor sister I cannot imagine the pain you suffered I am sorry I couldn't help you escape this harsh violence. They beat you, they punished you They burned you, they judged you. It is Afghanistan, where the people act as court and law. They took pictures and watched you burn. I want to write your name in red with black coal: Marta-yer Farkhunda. We will rename the Shah do Shamshera Farkhunda Road to honor your memory. I am sorry, my poor sister, all we can do is mourn, protest and punish these criminals for you. I know you sleep now in your grave, But this crime has taken away our sleep. We cannot enjoy the New Year because we still live in the old year. How can I wear a colorful dress while you wear your white shroud? Farkhunda, my poor sister, Forgive us for not being with you. Your name will be forever in our memories.

Mistake

by Basira

Not far from there, I see her running with joy. I hear her laughing, I read her writing, I listen to her teaching, I am inspired by her talent. But it was when I moved away, after I was separated from yesterday, I remembered when she cried; she was hit, before her voice rose up. After, she smiled, but her life was regarded as a mistake, which no one wanted to exist. When she went out, eyes stared and lusted after her. It is how it is there. My heart hurts with stopped breath, when I do not know if we are the wrong gender, Or if we are born in a mistaken place. We cannot choose these things ourselves. But it touches my tears when it comes in my mind and in front of my eye.

God’s Tears

by Kamilah

Once upon a time, I walked

on the clouds, talked

to the moon, listened to the stars,

laughed with the sun,

jumped up and down with the rain drops

into a deep ocean,

where fish were having a goodbye

party,

even though they were afraid of going

on a journey

of no return, afraid of saying goodbye

to the ocean of inhumanity and humans.

As I walked into the woods, the trees were shaking,

not because of the wind, but from seeing their friends

fall down on the cold, hard ground.

A mile further, I saw two birds

sitting on the branch of a collapsed tree,

looking hopelessly at the pieces of their fallen nest.

On that day, I believed the rain was God's tears.

She cried to show sympathy for her creatures.

She cried, cried deeply, and loudly.

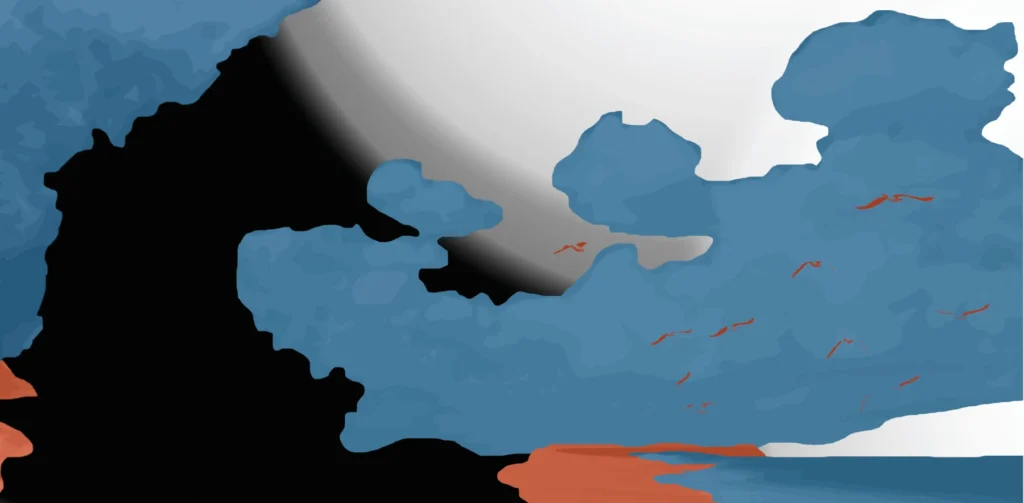

Ocean of Love and Death

by Mahnaz

Two people, both standing by the ocean--

one with a happy heart, the other with a wrenched soul;

one healed with hope, the other wounded with despair;

one with a free mind, the other tangled in black thoughts.

One sees love in the ocean; the other sees death.

One wants to laugh out loud, scream and run around;

The other miffed with unkind tears that left her alone

She holds a big knot in her throat

As waves form white ghosts with sharp, bright teeth.

Foam running from the corner of their mouths

hungry for a new prey; they run towards the sad heart,

like wild horses, stomping the ground.

Grabbing her ankles, pulling, pushing, the ghosts weed her from the ground,

slapping her with their white-gloved hands;

they chain her tight and pull her forward.

Then, scared sands give way, making a hole beneath her feet.

With sands' cowardly action, the sad heart empties her faith.

She looks to the pale sun, a sun that lost its power to black force.

The horizon is empty of delight, its blank and grey eyes, scolding her,

the sea birds turned to vultures, looking starved, waiting for her death.

The blue ocean seems dark to teh eyes of a disappointed heart.

The ocean bears no beauty but loss.

Ah--where is the courage to push her foward and strangle her in water?

She remains hopeless, filled with silence

But for the one with peaceful mind and happy heart

standing on the shore is ultimate joy;

the one watching birds, throwing out stones

Blessing her skin with the warm touch of sand

To her, the ocean is love, a source of relaxation

And the waves are angels, dancing towards her, opening

their wings, embracing her, inviting her to play with water.

The ocean depends on one's state of heart and mind.

Life is like an ocean

in the eye of each beholder; living can be death or love.

Like the waves of an ocean, life can have two faces--

Sometimes turning to beastly ghosts, sometimes to plushy angels.

Special Interview Feature

Lori Noack, Executive Director of the Afghan Women’s Writing Project

Tethered by Letters has been partnered with AWWP for some time now, but this is our first time featuring the AWWP in F(r)iction. Can you tell our readers about your work?

AWWP is a U.S.-based not-for-profit organization founded in 2009 by journalist Masha Hamilton as a response to the profound suppression of women in Afghanistan. Our aim is to empower Afghanistan’s women through the development of their individual and collective voices, providing a safe space for them to develop skills, exchange ideas, collaborate, and connect. Through AWWP programs, nearly 300 women have published nearly 2000 essays and poems that are shared with readers around the world, offering unique insights into Afghan culture.

The core of our program is a series of online writing workshops where over 200 writers work online with a team of international writers, educators, and journalists. Through our partner NGO in Afghanistan, we run a women-only Internet café/library in Kabul, and offer monthly workshops in seven of Afghanistan’s 34 provinces. These workshops differ from the online program in two key ways: First, they afford the women a place and time for community. Some women write without their friends or families knowing that they write for AWWP—the workshops offer them a safe place to congregate with like-minded women. Second, the workshops are led by AWWP writers who take on leadership roles. The seven provincial coordinators rent a facility for several hours once a month, order food, secure a guard for the duration of the workshop, and arrange for participant transportation to and from the workshops. Most importantly, they facilitate the workshop, often generating content of their own.

In 2014, AWWP expanded to include an online workshop for women writing in Dari, and in 2015 we will add an online Pashto workshop and open a branch in Ghazni province. These new activities open up opportunities for Afghan women who do not write in English. Other programs include providing laptops and Internet service for writers in need, radio broadcast of AWWP writings in local languages across Afghanistan, publication opportunities for our writers outside of AWWP, and an oral stories component to capture the voices of Afghanistan’s illiterate women.

Why do you believe that it is important for these women to share their work?

The ability to express our thoughts and feelings as humans is a crucial step in developing our sense of who we are. When we write our stories, we are able to both discover and craft our own narratives, leading to heightened awareness. We alter our perceptions as we interpret experiences on the page and are then able to project the new interpretations onto our future. Like airplanes in flight, if we are alter our path by even one percent, we end up in a different location.

Add these discoveries to being part of a workshop with like-minded and supportive peers and mentors and you have a group of writers able to reshape their defining personal stories away from the oppressive thought patterns ingrained by past experiences into an expanded narrative that creates new possibilities for the future.

What challenges do these women face in having their stories heard?

Our primary concern is always the security of the women, which is why we never share photos, last names, or other identifying information about our writers. Because we do not solicit for writers but only add via personal introduction and invitation, women who come to AWWP typically have some safe place where they can write, whether that is at school, work, home, or the writers’ cafe (if they live in Kabul). Still, women will often pull back for a time due to external pressures. We work with them to make the best choices for their personal safety. Some topics are more difficult than others to write about and while we never pressure the women, we also push them to break through fears and find a new inner strength that comes through processing and sharing their stories.

How does AWWP guide and assist these women through the process of writing?

For those of us working behind the scenes, our role is to continue sharing the writing with an ever-widening audience in order to validate the spirit and voice of Afghan women one by one. At the same time, we seek to nurture the spirit that connects us to one another. For us, this happens primarily through the Internet. It’s quite amazing, really, the AWWP community around the world, through which we strike up relationships, friendships. It’s important because it speaks to the fact that we all have something to contribute, whether we are readers, writers, commenters, or funders. AWWP enriches not only the 200+ writers in Afghanistan; it connects thousands of us around the globe, transforming each of us one word at a time.

Recent events (the murder of Farkhunda in Kabul) have brought some attention to the terrible situation faced by women in Afghanistan. How does AWWP give these women a chance at a better life?

A transformation is taking place in the hearts and minds of AWWP writers. They have gained a voice, are gaining strength in their very souls, even when conditions are not improving as rapidly as any of us would like. As if that weren’t enough, they are gaining language and computer skills, developing relationships with professional women around the world, and learning organizational skills that can transfer to the job market. They take part in organizing group events and are exposed to new and varied ways of moving through life. It is a very complex situation in Afghanistan, and our goal is always to nurture the creative spirit in the writers, that source that connects us as humans, the expression of which can be validated by others and therefore strengthened. And there are few populations as strong as Afghan women.

The work that these brave women have done to have their voices heard is inspiring. Can you share your best success story from your time at AWWP?

Success is a tricky word to define. The best responses to that question come directly from the writers’ perspectives:

Freshta says,

When I had sorrow inside of my heart and a pain in my eyes, [that] no one can see, I thought to write them down and share with the world… my life was dark and AWWP made my life colorful.

And listen to Nasima!

Four years ago before I started writing for AWWP I was a simple person who nobody knew. No one had knowledge of my…pains. Now people all around the world have communicated with me through their comments on the AWWP blog.

When my office manager saw my story…he decided to write about me for our official site. My writing has been published in other sites and in a book because of AWWP, and also in the Wilson Quarterly.

I received an invitation letter for the International Visitor Leadership Program from the American government after people at the American consulate read my writing and my personal story.

I can tell you that once I was only one lonely person, alone with my pains and my words and now I am part of a world.

What can our readers do to help these women?

There are many ways people can join the AWWP family, including mentoring (if you are a professional writer, editor, or teacher), writing notes to the women in the comments section of the blog, holding a reading in your own living room, or helping us publicize our new book this spring, just to name a few! You can even host a poetry slam at your school, as did two girls from Clarkston, Michigan, who raised $600 for AWWP at the event.

The easiest way, of course, is to write a check that will move this critical work forward. There is much to do in Afghanistan. And the women are ready to explore their potential and lead their country to a brighter future.

We also have a bilingual anthology coming out next month, Washing the Dust from Our Hearts. This is a special collection—please encourage your friends to buy and share!