My Son

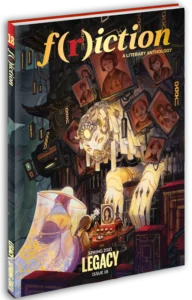

Words By William Pei Shih, Art By Noel Hill

I love my son. No one can tell me otherwise. If I am hard on my boy, it’s only to let him know that I am his Baba. In short, I am not his friend. This is because I only ever want the best for him, and because my son doesn’t know better, it falls upon my broader shoulders to show him the way. I emigrated from Taipei. I went to Florida State in Tallahassee. I learned to appreciate the delights of football. I once worked the night shift at a Dunkin’ Donuts, which is why I know firsthand, that one should always avoid the Bavarian Crème.

I am a food chemist. I work in Amityville, Long Island. Once a year, I’ll attend the company picnic. It’ll usually be held in a park, in the middle of the woods, and during the summer. Think frisbees and baseball under a bright, blinding sunshine. Think short-sleeved shirts and Bermuda shorts, a buffet of hotdogs and burgers. Almost always, there is a company raffle. Everyone in the company participates. It is supposed to be a bonding experience. The prize last year was a car. But I am a reasonable man. What I mean is that I know the raffle’s been rigged so that guys like me in mid-management won’t win. It’ll usually go to someone on the supply line. The raffle gives off the illusion of equal opportunity and something like the undoing of an injustice. But the real winners are those who are at the top.

Still, everyone leaves the picnic feeling good. The point is that I get to be there and that I get to bring my son for all the burgers and potato salad that he can eat. It’s so he can see me at my finest hour—so that he might gain a better sense of all that I’ve done for him, all that I’ve provided. When the time comes to think of his own future, here are the footsteps he might want to follow. Here is the person who he might want to emulate. Perhaps he might thank me, though I wouldn’t need him to. And for me, such things will be winning enough.

And yet, my son tells me that the fathers of his classmates take them to the museum. They attend their music recitals. They test their kids on spelling. In such cases, I have to remind my boy that I put food on the table and a roof over his head. Otherwise, he’d be out in the streets. Otherwise, come the winter, he’d freeze to death. Knowing my son, his chances of survival are next to naught. And the fact that I have to remind him is problematic. For one, he’s developed too much of an appetite for the comforts of life. He already gets piano lessons. He already takes taekwondo. He has a pet hamster. He’s named it Cody.

Furthermore, I have to remind my son that when I come home from work, I do not need to hear him tinkering away at the piano. Or see him out of the corner of my eye practicing his taekwondo movements. I would like to read the Chinese newspaper. I would like to watch the evening news. It’s not like he’s very good anyway, and I am not afraid to tell him so.

“It’s called practice,” my son tries to rationalize to me.

I wave my hand. I remind him that if he doesn’t shut his mouth, I can easily do so for him.

“Is that a threat?”

Okay, my son doesn’t actually say this. Of course, he doesn’t have to. But I imagine that one day, he’ll ask me outright and I’d better have my answer prepared: “Is that a threat? Well, if you want your Baba to show you, I will. After all, I’ve been showing you everything else, haven’t I?”

In Taiwan, I was in the army. Back then, everyone was obligated to do their two years of service. It was a hangover from the Chinese Civil War. I had been sent to the mountains where it was cold and damp. I was made to stay there for months. At night, I could barely sleep. There were dark days that I never thought would end. The point is, such an experience made me a man. I had to train, hard. I had to know what to do in case of any emergency. I put out fake fires with a long hose. I had to go through the motions of saving the injured, of saving lives. My own Baba was a colonel. During the Communist Revolution, he had served on the side of the Nationalists, the Kuomintang under Chiang Kai-shek. It was the side that lost. My mother and father were forced to flee Shanghai on the mainland. We left behind a home, our relatives, so many of our belongings. But that was how we ended up in Taiwan. My mother was already pregnant with me. The year was 1949. It was the year I was born—the year of the ox. There used to be a running joke in the family. I was already in my mother’s belly in China, but I was born in Taiwan. When my Baba told it, no one really laughed. But we understood that it was supposed to be funny.

I myself am the eldest of four ambitious brothers. When we were kids, my brothers looked up to me. I was the first, so I made the mistakes in order so that they could fare better. What I mean is, where I made errors, my brothers only improved. This was why they were able to advance further. It was the sacrifice I made for being the first. Eventually, my brothers thought that they were better than me. And that was their mistake. My own Baba called me “stupid.” He’d call me “stupid” before my brothers at the dinner table. We didn’t say what it was then, but the man was depressed. He knew that he would never see his home again in Shanghai, nor would he ever see his family in Henan. He would never see his own siblings. But my father felt that he was on the right side of history, and in the end, that was what mattered most, for a time. I, however, knew that it was a punishment from the Heavens, and another part of me believed that he deserved it.

And yet, there are instances when I find myself moved by self-reflection. I’ll finally come to understand my own father a bit more. I don’t call my son “stupid” at the dinner table, even though admittedly, there are times when I think that he should hear it. In return, I expect my son to sit there, to eat the food that his mother has so carefully prepared, and to listen to me talk about my day at the lab. I might tell him about my discoveries—or more often than not, what I don’t discover but hope one day that I will. If I’m in a foul mood, I might not speak altogether. Nevertheless, I still require my son’s presence, his utmost attention. I’d rather not allow him to excuse himself. For if he does it once, I know that he’ll think he can do it again, and one never knows what such diversions might lead to. If he goes to his room to watch TV, or to listen to music from his stereo, it will fill me with such a blinding rage, and I know that ultimately such things will only prove to be counterproductive.

But when I watch him eat, it’s almost as if he’s eating from my very hand. At the age of thirteen, he is a growing boy. Still, I know that he will not be taller than me. Not yet.

My son is of a sensitive disposition. It is another problem that I foresee. He likes the art museum in the city. He likes the music of Beethoven. When he is bullied in school, he doesn’t fight back. He’d rather get punched one day and hold out hope that later on he still might be able to form a friendship with his bullies. In short, I know that there will be other lessons that I will have to impart on the boy. Some of these lessons, I will have to wait on. I have to pick my battles.

But I do drive my son to the park by the bay. When we get there, I shove a basketball into his hands. We find a near-empty court. There, I make him shoot two-pointers for an hour or so. One hundred points. Two hundred. I tell him about my brothers. “This is what we used to do back in Taiwan.” “This was how we bonded when we used to bond.” “We loved it. We loved each other too.”

On this day, my son and I go on for another hour. A dreaded dusk descends. I try to ignore the fact that other boys would love the chance to play against their fathers, but not my son. I can see that he is afraid of a little competition. My hunch is that he hates to lose. Only it’s worse. He’s willing to give up before we even end the game. And on this day, my son decides to be difficult. He wants to go home, he says. It’s cold, he says. He looks up at me with his dark eyes, full of daggers, as they say.

It’s okay, I tell him. I can be difficult too.

The next day, my son brings home an additional hamster. I can’t help but take this as one more example of how oblivious my boy has become to all that I’ve done for him. As I’ve already mentioned, he had begged me to get him the first hamster from the basement of Woolworths. And as I have already mentioned, he had named it “Cody.” I had bought the pet for him in a moment of weakness. I thought that having a hamster might teach my son something about responsibility, and even appreciation. In the end, I’m the one who feeds it and cleans its cage. Cody is golden and bright-eyed. It is energetic and bites the bars on the cage. One can even hear the metallic rattle all throughout the night, and more often than not, it keeps me up into the early morning hours.

The new hamster isn’t golden, nor is it bright-eyed. It is actually quite ugly with its messy gray fur and its pink snout like a pig’s. My son explains. It was given to him by a classmate from school, or so he says.

I refuse to shell out the money for another cage. But my son says that it’s okay; he’s already saved up enough for another. It doesn’t matter that I tell him that it’s a waste of money. The next day, he will take the bus to the Petland on Main Street. Stock up on supplies. It isn’t exactly music to my ears. For now, the rodent lives in a shoebox.

At the dinner table, I tell my son about my day at the lab, about the experiment that went nowhere so we have to try again. And how I’m willing to try again and again until I get it right. He holds up a finger and stops me mid-sentence.

“Excuse me,” he says. Before I can oblige, he adds, “I should go check on Teddy.”

“Who’s Teddy?”

Later that night, Teddy escapes from the shoebox. It somehow finds its way to my room, down the hall. Then it is in my bed. Now I wake with a start. My senses clarify. Moments later, I find my fingers dripping with blood. I must have startled the rodent and so it bit me. In retaliation, I fling it across the room. It hits the wall, plops to the floor. But as I am trying to wipe the blood from my fingers, I see the little thing make its uneven way back toward my bed like a winded beggar. I consider killing it right then and there. In the army, we used to kill rats. We used to shoot birds for target practice. Still, I think to bring the hamster back to my son’s room.

The commotion wakes him. I see my son through the darkness as he rubs his eyes. At first, he’s too groggy to understand, no matter how much I try to tell him. But when he sees me with the hamster, pressed facedown against the floor, he gets the message. Then I watch my son cry.

“No, don’t do it,” he whimpers. “Please, Baba, don’t.”

Now I am no monster. But the fact that my son thinks me capable of such an act only upsets me further, and I am already upset. So I say to him, “Calm down.” I feel the thing squirm beneath me. “It’s alive and well.”

And yet, my son cannot stop his tears. I can hear him plead and plead, but for what? I’m the one who’s still bleeding. I’m the one who’s still in pain. But does my son care?

I leave the hamster be. A bit stunned, it doesn’t go very far. No doubt my blood is still on its teeth.

And then I hear my son say it, “I hate you.” Somehow his voice is even higher than ever. “I really hate you,” he says again.

“Don’t be stupid, boy. Go back to sleep.” Outside the window, I can just make out the beginnings of a twilight.

“No, actually,” my son then says. “You’re the stupid one.”

At the door, I pause. “Oh, really?”

In the morning, the neighbors ring the bell. They come with concerned faces. They want to know what happened. “Is everything okay?” one neighbor asks. She is a woman in her mid-sixties. Her name is Minnie. Indeed, she’s been our neighbor for close to ten years, and she’s never once come to the house. Now she’s shaking her head at me.

I smile the best I can. It’s the smile that I reserve for white people. “Of course. Everything’s okay. Nothing to worry about.”

“But I heard yelling last night. I heard crying.” Then, “I was about to call the police.”

“Everything’s all right. Don’t you worry.” I want to add that she should mind her own business. But instead, I wave. I nod. I smile some more. I smile harder.

Then I close the door on Minnie. I look out the window. She is a full-figured woman in a pink muumuu and slippers. I watch as she makes her way up her driveway and then back inside her house and through the side door. I take in the quietude around me. I realize that I don’t know where my son is. But I know he’s gone out. For once, he had been up before me. I don’t think he slept a wink.

It doesn’t matter if my boy doesn’t speak to me for a week. I will not call after him. He will have to learn that I can hold my breath for just as long as he can, even longer. He’s mistaken if he thinks he knows me at all. I can hold it until it hurts, until I’m black and blue.

Then, of course, there is the trip to New Orleans. In fact, I’ve not been to the city since my days at Florida State. I had once gone by myself, as a little getaway. It was a big deal for me, as I’m not one to take trips. But my son and I are there for the Chemistry Food Expo at the convention center. We sample the food at the different booths. We try tuna fish ice cream and pigeon stir fry and dragon fruit cake. It is crowded. People are making connections left and right, exchanging business cards. I pass out a few myself and collect handfuls. In the evenings, we dine at restaurants that we normally wouldn’t have the chance to go to. I’m no fan of eating out. Too much oil, and not to mention, too expensive. But here, we will have no other choice. I don’t even know how we can eat anymore after a day of sampling food at the Expo, but we do. Oysters, muffulettas, gumbo, beignets for dessert and the chicory flavored café au lait at Café du Monde. I like beans and rice because it reminds me of the food from Taiwan. But my favorite is the crawfish because it also feels most like I’m getting my money’s worth when I eat it, and I swear, it only enhances the flavor. As a food chemist, I can say that there is no chemical formula that can do it any better.

The next afternoon, I go to the Food Expo myself. I have to say that it isn’t the same without my son. Still, I try some samples. Still, I dole out business cards and collect even more. But when I return to the hotel, I find a bag of crawfish sitting on the air conditioner. Our room doesn’t have a refrigerator. I know that my son had had to walk from our hotel to the French Quarter in order to get it from the fish market. He might even have had to ride the streetcar. My heart swells with pride. “My boy,” I say. After a day of sampling food, I shouldn’t be hungry. But I devour the bag. My son doesn’t eat any of the crawfish. He doesn’t want to eat something with eyes, he says. He doesn’t want to eat something with so many legs. But it doesn’t bother me, not in the least.

It’s the first trip that we’ve taken together. And we actually talk. I get to see another side of the boy. He doesn’t say a lot to me, but it’s in his actions. Like the crawfish. Like our evening walks through the French Quarter after the Food Expo. He likes it. I like it, too. I think that this is what it can be. In fact, this is what it should be.

My son’s favorite street is Royal Street. He likes to look at the paintings and the antiques in the shop windows, and the crystal chandeliers and hand-carved wood furniture and silverware. My favorite street is Bourbon Street. I like the bright lights and the vividness of it all, a feast for the senses. Everyone seems happy. But also, I like to walk along the riverfront and gaze upon the Mississippi River and see the steamboats and listen to the jazz music that seems to flow from them and carry over the water in the still of the night. It’s there that I get to tell my son about how I couldn’t compete with my brothers in Taiwan. Not at school. Not even in the army. Eventually, they were even able to outplay me in basketball. Instead of food chemistry, they all went into computer programming. It was the 1990s. It was the rise before the fall. For a time, my brothers lived it up. Houses in the suburbs. Fancy cars. A Gateway 2000 computer in practically every room. They already had the advantage of confidence, which counted for a lot. And yet, like Icarus, they flew too close to the sun. I only know of Icarus from my studies in high school. This was back in Taipei. My teacher then, Lim Tai Tai, had had a passion for Greek mythology. And because we were in Taiwan and not the mainland where the Cultural Revolution raged, we could read such things like The Odyssey. The point is, there is always more to the story.

“That was how they lost their fortunes,” I add. “I’m not saying I’m happy about it. I’m saying that they wanted too much. The Chinese word for it is ‘tan xin.’ It means ‘greedy heart.’ They thought they could be like white people. So you see? Greedy heart.” Then I say, “So who is the stupid one now?”

My son doesn’t like the hotel we are staying at. The bed is too hard, he says. The TV doesn’t work. So we move a little further down the street to another hotel. We check in. The bellboy takes our bags. The room is far better than I expect and almost worth the price. There is a living area with a couch. There is a bathtub. The TV has HBO.

The next afternoon, I decide to leave the expo early. Enough free samples, enough business cards. My son and I visit a swamp in the bayou. We buy tickets for the tour. On it, the guide tells us about his family. He has two daughters. He even passes around a photo album. “This is my old man,” he says. He points to a photograph of a wrinkled man in a red cap and wearing jeans, smoking a long pipe. Then he takes us to see the alligators. He feeds them whole chickens, and the gators devour the raw meat. The guide gives my son one of the baby alligators to hold. At first, I think that my son will be too afraid. But he isn’t. Outside the boat, the air is muggy. There is not a single cloud in the blue sky. After the tour, I leave the guide a twenty, even though I know he’s been angling the whole time for tips.

Later still, my son and I are back in the city. There is the jostling of tourists. We push our way through to see a brass band play. We are on Frenchmen Street. There is something in the air, something like cinnamon. We’re drawn to an outdoor market. At a stand, a woman sells us homemade soaps. They smell of jasmine. I end up buying two, which I already know I’ll never use.

Okay, none of this has actually happened. Not the swamp tour, nor the Food Expo. Not the splurge on the jasmine soaps. At least, not yet. But I can already see it all in my mind’s eye as if it’s yesterday. I know that it is only a matter of time. And there’s nothing wrong with having high hopes.

The warmest of evenings, a sky filled with stars. The sun-filled days that almost never end. Light so bright that it sparkles over the Mississippi River.

At this year’s company picnic, it rains like hell. It is the middle of July. We all have to crowd under several tents in order to hide from the downpour. It’s a pain. There are barely any seats left at the long wooden tables. We’re packed like what some might say are sardines. Despite all this, the festivities are in full swing. Children can be heard laughing around us. There is music and even dancing. For a moment I think of how it says something about the power of the human spirit—its unrelenting ability to persevere. Once again, there is the lottery. The prize this time is an all-expenses-paid trip to Tahiti at a five-star resort.

As expected, I lose.

But I am here with my son. We are in line for the buffet. When we get to the trays of food, I grab a paper plate. Have a burger, I urge. Have a hotdog. “Don’t have just one, have two. Have three.”

It’s then that my son tells me the news: he’s now a vegetarian. I can’t help but scoff.

When we find a seat at the corner of a table, I tell him that being a vegetarian is nothing short of wasteful. I tell him to think of all the people who are starving around the world. I tell him that when I was growing up in Taiwan, my brothers and I didn’t get a chance to pick and choose what we wanted to eat. There were always shortages, not to mention inflation, which made it all the more difficult to get what was already not enough.

“Baba, why do you hate me?” my son then says.

“What do you mean? I don’t hate you.”

“Then how come you never say that you love me?”

“Why do I have to say it?”

“I guess you don’t.”

I see my boss. I wave to him. He waves back. I see several of my colleagues in mid-management. I say hello to them too. I shake their hands. I introduce them to my son. My son says hello. Me and the rest of mid-management talk of how we still have to get that beer and watch football. We’ve been saying it for years now, but I still like to keep the door open, just in case. After all, I am one of the few Chinese people here, and among all the faces that aren’t like mine, it somehow feels like an accomplishment. My son is having his potato salad. He’s having coleslaw. I am on my fourth burger, and I am already thinking of getting another.

I get my fifth burger. When I return to the table, I say to my son, “Eat something more, I’m begging you, please.”

“I can’t.”

I then point to all the food on display, cakes and strudels too. I know most of it will soon be thrown away, which is a shame. “Literally everything you could ever want to eat at your fingertips, and all you can say is no.”

“Well, what else can I say? I’m full.”

“What about dessert?”

“Dessert? No more dessert.”

And then I know what to say. In fact, I’ve prepared for it. “New Orleans.”

“New Orleans?” my son reiterates.

I tell him about the Chemistry Food Expo later that summer. I tell him that I am willing to splurge on the decent hotel. I tell him about the French Quarter and the swamp tour. A stroll along the Mississippi River. I tell him about the first time I was there as a student at Florida State.

But he shakes his head. “No way.”

“What do you mean no way?”

“I can’t go with you to New Orleans.”

“And why not?”

“Because I’m not going to have any fun.”

“But it’s not about having fun. It’s about spending time with your Baba.” When my son is quiet, I feel the need to add, “Do you think that I ever needed your grandfather to say that he loved me? No, and do you know why? Because I listened to him. Because I read between the lines. Because he was a colonel during World War II. Because he had served under Chiang Kai-shek, and therefore he had to leave everything behind in order to save our lives. Because you wouldn’t even be here if it weren’t for him. Because he could barely provide enough milk and eggs for me and my brothers. But still, we were able to survive. We were able to make something out of nothing and more importantly, make something of ourselves. So don’t speak to me of love, because you don’t even know the half of it.”

“I’m still not going to New Orleans.”

“You’re going and that’s final.” Then I say, “Because I’ve already bought the plane tickets.”

My son looks up, flabbergasted. He knows me well enough to know that there’s no chance that I’ll make the effort for a refund. In short, what’s done is done.

“Well? What do you say? A ‘thank you’ would be nice for a change.” And then, “Don’t make me make you go.”

“Is that a threat?”

“Yes. It is.”

At first, I think that my son is speechless, too much emotion, too much to wrap his head around. I sit back. I wipe my mouth with a paper napkin. I brace myself for possible tears. Then he says, “I know why none of your brothers talk to you anymore.”

My son and I don’t talk on the ride home. I pretend not to mind. Outside, I present a cool and calm exterior. Inside, I fume with a rage and angst that doesn’t seem to dilute itself in the solution of time and space. I play music in the car, turn up the oldies station. I look out the window. On the highway, I speed by other cars as if it’s a race—and I’m the one who’s winning. It is no longer raining, though the sky is still overcast. There is still a pervasive sense of gloom.

We don’t go home yet. By this time, my son has fallen asleep. But when he wakes, he looks out the window and he says to me, “What are we doing here?”

“Get out of the car,” I reply. In the trunk, I get out the basketball. I lead him to the court. There are puddles of rainwater everywhere; neither of us are dressed properly in polos and khaki pants, but I don’t care. I say to him, “You’re going to shoot two-pointers until you reach a thousand.”

I shove the basketball in his hands. “Start counting,” I say.

He dribbles. He begins to shoot. I watch him miss, again and again.

By the time we get home, it is already late. I can see that my son is exhausted. But I am too. He says that it’s his arms and legs; they hurt. He says that his head hurts. I tell him good. I tell him it’s how one builds stamina, and not to mention muscle, and not to mention character, and not to mention . . .

Before I can even finish, my son manages to stomp up the stairs. Then I hear him slam the door to his room. I think of how it isn’t the first time that he’s done this. And then I think once again how one has to pick their battles, and this is another that I’ll have to keep in mind for later. Only I hear the door to his room open. And then I hear him make his way across the hall. He can’t even obscure the tiptoeing. When he’s in the bathroom, he closes the door. I hear it lock. I wait fifteen minutes. When it’s half an hour, I knock on the door. “What’s going on in there?”

I grow impatient. I then say that I need to use the bathroom, and if this is some attempt at revenge, I’m not afraid to take apart the door.

“Well?” I say.

When the door unlocks, I open it. I see my son. He is on the floor. Beside him, the tiny body—golden brown, Cody. The hamster is laying on its back over the carpet, paws against its belly. There are bits of green bedding clinging to its fur.

“Not that you care,” my son says. “But he’s dying.”

I watch my son. He looks gutted. He looks absolutely miserable.

“Move aside,” I say as I kick off my slippers.

“What are you doing! No freakin’ way!”

And it’s then that I feel it, smack right across the face. In fact, my son hits me so hard, he knocks off my glasses.

“What the hell are you doing?” I say. “I’m trying to help. Don’t be stupid.”

I rub my cheek, pick up my glasses off the floor. I actually feel pain. I know that I’ll need an ice pack later on. I can’t help but be surprised by the boy though. Maybe he’s like his Baba after all—stronger than he looks. Maybe there’s some hope for him yet. And maybe by the time this bruise heals, my son will have a better sense of what it means to be like his Baba. He’s standing there before me, fists raised as if he’s about to do it again. This time, I move gingerly towards him, my palms, open. It’s not quite surrender, but it is a compromise. “Let me see what I can do, okay?”

As I watch my son relent, I try to tap back into my army training from Taiwan. I kneel before the hamster. Its eyes are closed. Its little teeth, protruding from its mouth. Its breaths are deep, and they are slow in between. I use my index finger, touch its stomach. I try to feel its little heartbeat. Then I try something that resembles CPR. Behind me, I can hear my son saying, “please, please, please,” to no one in particular. And then I hear him actually praying. I wonder where he even learned how to pray like that.

In an effort to revive Cody, I pet its body a little more. I feel its fur, still soft, still warm. Only none of what I do seems to work. And soon enough, the inevitable becomes the inevitable.

“Is there anything else that you can do?” I hear my son say. His voice, high. We wait for the miracle that doesn’t come. I watch the thing take its last bit of breath, and see its life leave the small body like an evaporation of the spirit. Then I shake my head. I don’t know what else to say. Neither of us do. For a while, we can only stare at the body. Eventually, my son picks it up. Now it looks like a rag doll, limp, lifeless. Still, he cradles the creature in his arm as if it’s a newborn baby.

I can’t bear to watch though. I know that I’ve disappointed the boy, failed him again somehow. In the years after, it’ll be another thing that he’ll come to hold against me. I find myself saying, “Tomorrow we go to Woolworths. I’ll buy you another one. We can buy two. We can even buy three. We’ll buy them young so they can live the longest.”

“It doesn’t work like that,” my son says. I see him wipe the tears from his face with the back of one hand. “It’s all right, okay? You did the best that you could.”

I shake my head. “Look son, we both did.”

Taiwan, dawn in Taipei. We are already at the park, on the basketball court. The court is empty; it’s as if we have the entire place to ourselves. I am there with my three brothers. We dribble the ball, pass it between us, back and forth. One at a time, we take shots at the hoop, play for what feels like hours. I can hear the scuff of our sneakers, the panting of our breaths. Naturally, I score more points than the three of my brothers combined. It’s a single-handed feat. They are amazed. I think that I can luxuriate a little longer in such victories. But I don’t. Instead, I cave, I fold. One by one, I teach each brother my trick. I show them how to shoot at the backboard so that the ball bounces into the net. I watch as my brothers try it. They each give it their best shot. They try until they get it perfect. I can’t help but think that we will be the greatest team ever, undefeatable, and that it can’t get any better than this.

Only it does. Because there, at the fence, I spot the familiar tall and dark figure. We all see it—our Baba. He’s come to watch us. He’s come to spend some time. It’s like our hopes being heard and felt all at once. How long has the man been standing there? It doesn’t matter. We show off what we can do. We shoot hard. We dribble fast. We run faster.

All of us do so with the hope that our Baba will join us for just one game. But of course, he doesn’t.