Yurássic Park

Words By John Manuel Arias, Art By Brian Demers

“A person doesn’t die when he should, but when he can.”

—One Hundred Years of Solitude

Esteisy Contreras had no idea what she was walking into when she accepted the job. One uncomfortable afternoon, her cousin mentioned that a new, gringo-run resort was hiring on the island called Isla Nublar. “I heard it on the radio. They need an army of maids,” Mariana said. “I would go, but Ignacio doesn’t trust me so far away from him. He’s heard the rumors about my sister and thinks running off with rich gringos might run in the family,” she teased, determined to lighten the mood. But the pale band on Esteisy’s finger and the fading lilac shadow around one eye turned Mariana’s tone serious. “Go, Esteisy. It’ll be good for you to get away.”

When Esteisy arrived at the recruiting office in Costa Rica’s western port of Puntarenas, they hired her on the spot. The salary seemed fair, and she could send back enough money to her ailing mother, whose diabetes had claimed a foot earlier that year. Esteisy asked when she could start, to which they pointed to the helicopter at the end of the pier. InGen was slapped on in blue paint toward the silver, rotating tail; a handsome gringo in aviator sunglasses loaded packages into its cabin. Out of either desperate hope or a woman’s intuition, she had already brought her luggage—colorful blouses, a Virgin of Los Ángeles, some worn dancing heels, her first edition copy of One Hundred Years of Solitude—all her earthly possessions stuffed neatly into one compact suitcase. Her unearthly possessions, however, she left scattered there on the beach, staring back at her as the helicopter floated like an ember over the turbulent sea.

The thirty-minute ride consisted of awkward silences between herself, the Costa Rican man next to her, and the handsome gringo who reeked of sunscreen. Esteisy spoke little English and had been taught since childhood that gringos are notorious perverts. Give them the wrong type of glance and they pounce, no matter how cosmopolitan they seem.

“Gorgeous country you got here,” the gringo winked. Esteisy nodded politely and turned her attention to the man next to her, whose cat-green eyes shone brighter than the gringo’s.

“I’m a zookeeper back in San José,” he said without looking at her. “I bathe and feed the lion everyone calls Bob.”

“The one with dreads?” Esteisy asked with a smile.

“That’s the one. You’d be surprised at how docile he is. A regular crooner if you brush his mane right.” Though he was only about thirty, he spoke with the confidence of a cynical old man. His voice gruff, the hint of a lion’s roar somewhere beneath.

All Esteisy could remember of the Simón Bolívar Zoo were its tropical birds—the dozens upon dozens of macaws, toucans, quetzales, motmots, and the occasional peacock. Most of the animals were originals from when the zoo first opened in 1921, so the parrots still recalled the austerities of the Great Depression. And having once been owned by great writers and dissidents, they sporadically repeated Communist propaganda.

To any potential comrade they cawed, ¡Compañeros! ¡Patria o muerte! ¡Venceremos!

Esteisy’s anecdote left the zookeeper chuckling. He too had almost been painted red by the birds. “But what’s a zookeeper doing at a resort?” she asked. She imagined llamas with humid fur, a pig maybe, and fattened goats tethered to the ground.

“What resort?” the zookeeper said. “We’re going to a nature preserve.”

“It’s more of a theme park,” the handsome gringo interrupted, sniffing the white paste on his arm. “Unlike anything either of you have ever seen.”

Esteisy both understood and misunderstood the gringo’s revelation, and immediately her stomach churned and fell through her body into the sea. Uncertainty sat in the empty space between the three helicopter passengers, and by the looks of it, she seemed to be the only one it daunted.

The island lived up to its name. A permanent cloud caressed its soft mountains so that from far away, it took on the mien of a gray-haired skull buoying in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. The sun made skimp appearances, and Esteisy’s beautiful tan gradually dissipated, as did her already thinning tranquility. Yowling broke the silence of dry nights, hushing the cicadas, intensifying her nightmares. These animal noises brought her back to the small coffee latifundio where she was raised, where tenacious bands of coyotes grappled with jaguars twice their size. Esteisy lay hyperventilating many nights, gaping at the darkened bunk above her, feverishly analyzing the roars, relying on her bunkmate’s snoring to lull her back into unconsciousness. A full night’s sleep eluded her as an important dream eludes one who has just woken from it. In the daylight, half her wobbling mind longed to return home. To sleep again in her mother’s bed. Despite her insomnia, however, the facility of her job was enough that she abandoned the idea of leaving. And besides, she needed the money.

Every morning Esteisy jerked awake at five, poured her amphetamine-strong coffee and lugged her aluminum mug as she passed through the labs, offices, and guest rooms; dusting, sweeping, vacuuming, and mopping up strange liquids on the floors. The cleaners reminded her of the ones required in the government hospitals—a nauseating, ammonia-rich scent meant to annihilate every type of organism. She worked with a pink handkerchief tied over her mouth and nose. The other maids cackled and called her bandida, as if she robbed trains in her free time. Esteisy befriended them easily though, all being Costa Rican women much older than she was. Some like aunts, others with her mother’s sweet face. They toted her around on their shifts, administering sobering advice, confessing their own run-ins with demons back home. Sightings of the headless priest, La Llorona, the disconcerting rhythm of the cart without oxen. These childhood legends warned of monsters with missing things—a head, or children, or oxen. And for these missing things they scoured this world and the next, sometimes settling for anything remotely similar—another’s head, or children, or livestock. The yowling here disquieted everyone’s dreams, and nostalgically they all wondered what monsters roamed this island. What missing things they were searching for, and how far they would go to reclaim them.

To ease their minds, the Costa Rican staff threw ecstatic parties on the weekends. They danced like gallant animals in their quarters (curiously the only building on the whole island without high-voltage fencing). At one of these fiestas, Esteisy ran into the zookeeper again. He had become more rugged since their helicopter ride—his beard almost full-grown, the bags beneath his eyes overflowing with the unearthly possessions he’d been foolish enough to bring with him. On the dance floor, he introduced himself as Victor before sweeping Esteisy off her feet to a bolero played from a shaky phonograph.

“My mother would say you dance like a rooster,” Esteisy said.

“What else does your mother’s voice say?” He tightened his arm around her.

“She would say you’re trouble.”

“What else?” He touched his lips to hers.

“She would say to make you work for it.”

“Oh, I will.”

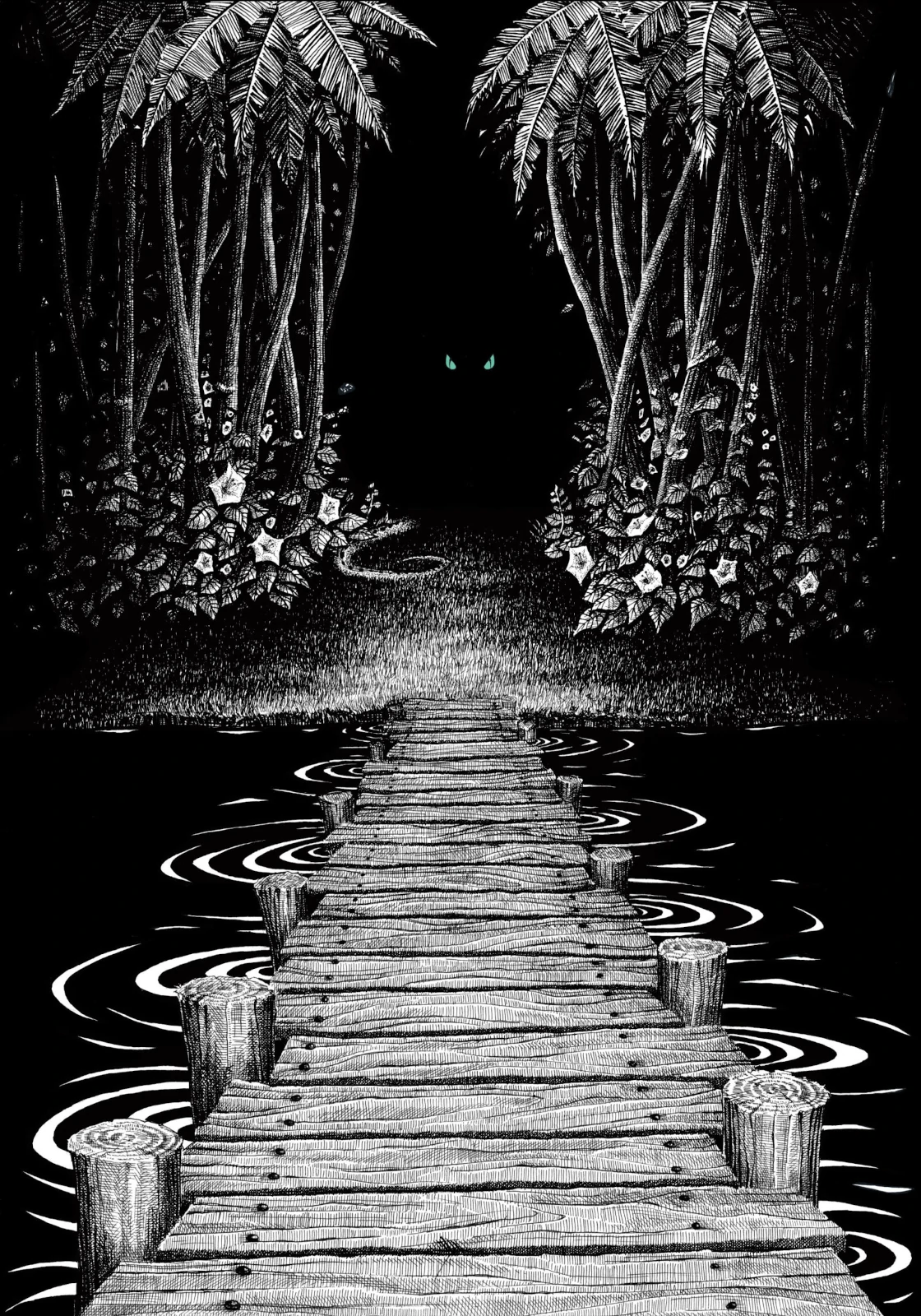

After the last shot of guaro was taken, and even the most incorrigible sot lay collapsed and snoring on the floor, Esteisy and Victor wandered from the workers’ quarters to the beach. In the distance, a thunderstorm brought the mainland into view. Lightning cracked the eastern sky with hairline fractures, and their homes peered back at them like a mirage. Victor lit Esteisy’s cigarette, and they sat beneath a palm together.

“What kind of animals are here?” Esteisy asked bluntly.

“I can’t say. I’ve signed a contract.”

“Because they’re illegal?”

“No,” he said, studying her curiosity with his own. “But they should be.”

She caressed his arm and detected a scabbing gash, almost the length of a riding crop. “What happened? Are you alright?”

“It’s nothing,” he said. Then he kissed her to shut her up. Illumed by the far-off storm, they transformed into beasts and tore off each other’s clothes. Victor found all the secret parts of her: hidden, milk-white patches of flesh, her still-tan ones, a series of stretch marks like an electrical storm around her belly. He kissed them all with a tenderness unfamiliar to her. As if he planned to plead her mother’s permission for marriage. She kissed him back with unfamiliar tenderness, sniffing the musk on his chest, the thick hair underneath his muscular arms. The midnight yowling couldn’t be heard over their moans. Together, they ran lip-locked into the sea. Panting, rib-deep in the tide until it receded, making love on the frothing sand when it finally did. After that night though, Esteisy would never see Victor again.

Rumor had it he’d been mauled by one of the animals, his torso shredded open like an excited child’s gift. His bunkmate and supervisor Luís told everyone he had never seen so much blood. Luís had dozed off at his post and arrived after it was all over. Landing on the platform where Victor lay, he had almost slipped on the still-flowing blood. Esteisy’s coworker Blanca corroborated his story, admitting that she’d had to mop it up later. “I scrubbed and scrubbed, but still it pooled like a lake on the floor. And in the paddock where he was attacked, I felt evil staring back at me from the leaves. It smelled like sulfur and chicken flesh.”

“Raptor,” Victor had gurgled as his unwrapped body went limp.

“That’s all he could say,” Luís whispered.

The gossipers avoided each other’s gazes, looking instead to the surrounding forest. An impenetrable, emerald wall closing in on them like a booby trap.

Raptor triggered a recent memory in Esteisy—a bubbling tank labeled Velociraptor mongoliensis. While cleaning the main lab, she had touched its warm glass. In its center was suspended an embryonic creature, like a white lizard curled into itself.

What fiendish things called this island home?

What new evil could these gringos possibly unleash?

Before she could retell it to the others, a butterfly landed in the center of their table. As black as wood eaten by a bonfire. As clear a sign as a confession.

That night, Esteisy cornered Luís in his room. She pointed to his hard hat, a hollowed-out tangerine half with a circular, yellow logo of words she didn’t recognize. “What is this place?” she growled through her teeth. “Where are we, Luís?”

“Yurássic Park,” he shrugged. “That’s what the gringo overseers call it.” He continued packing his few earthly possessions: his grandfather’s pipe, the New Balance tennis shoes his ex-wife had presented to him for their last anniversary, blood-stained gray slacks. He’d been sacked that day but was expected to finish out the week. His superiors blamed Victor’s death on his absence. And by his countenance, so did he.

“And what is that thing?” she said, her finger’s aim steady on the hard hat.

In the yellow logo, a black, skeletal creature emerged triumphant. Its teeth longer than its arms, its eyes scooped out but still searching.

“That European’s legacy,” his voice broke.

The European? The owner, he meant. The wrinkled prune of a man with teeth brown like tobacco. His skin as pale as his suit and panama hat. He stalked the grounds, speaking English differently than the gringos, ogling at the maids as they dusted the feet of the giant skeletons in the grand hall. Sitting, twirling his cane, every so often calling one up to his office for a chat. Blanca had warned Esteisy to make herself scarce, to dodge him at all costs. A young one he’d yet to have and his appetite rivaled that of even the beasts on this island.

“There are many monsters here,” Luís said. “Some worse than others.”

Esteisy spent the remainder of the week planning her escape. She was told by her own supervisor that a stipulation in her contract allowed trips to the mainland once every six months—the only other way was to cross the sea on a stretcher. On his face, she saw the same shame and dread she’d seen on Luís’s. Yurássic Park’s management knew something the rest didn’t.

The following day she gathered her fellow maids, trying to rouse a mutiny, to convince them of the doom they had all seen land on the table in the form of the black butterfly. But the women—even the ones with her mother’s sweet face—turned away. They flipped through the rolodex of their bills, debts, IOUs; a diseased sibling’s care, a child’s expensive American school, a husband’s extensive bar tab. The emotion between necessity and responsibility outweighed intuition, and Esteisy realized any flight from the island would have to be carried out alone.

That Friday she left her earthly possessions beneath the bunk—her Virgin and blouses, the magical Buendías family. While a goodbye fiesta for Luís raged on with singing and guaro, Esteisy slipped out of the quarters and started on her way to the eastern dock, where she’d heard a rumor that a low-security cargo ship was leaving for Puntarenas. But it began to rain. At first, heavy drops, no less dense than bullets. Then, a maelstrom. Wind and a mortar of water crashed down onto the road, and Esteisy took cover beneath a ceiba tree. She was unsure whether what she heard next was thunder or a murderous roar resounding throughout the forest, frightening the birds that had taken cover in the branches. Fear unstitched the tendons in her ribs, and Esteisy vomited.

Her plan had been foiled. Nature’s cruelness had condemned her. Again.

She sprinted back down the road to the quarters, but two high beams appeared, quickly moving closer while she stood like a frightened deer. She jumped to dodge a jeep hurtling through the artillery of rain and landed hard on her belly in the mud. In a heightened panic, she checked her abdomen with both hands—a ghostly reflex, long vestigial. This time, her aching stomach revealed only anxiety. When the engine’s noise receded to the east, Esteisy heard a new, terrifying sound. Footsteps in the underbrush. A slow, careful rustling of the leaves. Chirps wafted from both sides of the road, and Esteisy kept still until they stopped. She picked herself up and sprinted again, faster than she had ever run before.

A trident of lightning carved the fenceless quarters out from the rainy darkness. Bursting through the doorway, Esteisy crashed into Blanca, who wavered in a drunken breeze. Candles illuminated the common room, where everyone swayed and chorused.

“Diay, Bandida! You look like hell,” Blanca giggled. “Did you go out for a stroll in this storm? We looked everywhere for you when the power went out. Come, have a drink with us!”

Too cold and wet to answer, Esteisy walked like a specter through the party back to her room. She snatched the Virgin of Los Ángeles from the suitcase and began praying. Calling on her mother, her grandmother, and every other woman who had ever loved her. Searching her past frantically for protection and guidance.

It didn’t register that she had left the front door wide open.

Screams exploded from the singing. The gay voices turned to those of horror, still in almost perfect harmony. Crashes and shrieks, both human and not, ripped Esteisy from her prayer. She crept to the bedroom threshold and saw that down the hallway in the candlelight, monsters pounced and gnawed on the partygoers. Their slick bodies somewhere between bird and reptile, standing taller than the tallest man she knew, obsidian-black talons jutting from every appendage. They slashed open the skin on the back of her friends’ necks. One cradled Blanca’s head in its teeth, just as one might sink their nails into the peel of an orange. Esteisy searched her room for an exit—the only one being a tiny window too high to reach. After locking her door, she dragged the bunk to the window’s ledge as quietly as possible, even though to her it sounded as if its legs grated the linoleum floor. Suddenly, hysterical knocks pounded the door—Luís yelled from the other side, pleading and howling like a wounded dog.

“Let me in, Esteisy! Please!”

But for a moment, she hesitated.

“I swear it wasn’t my fault—don’t do this to me!”

Regaining control of her heart, Esteisy abandoned the bunk and jumped to let him in, but the rapping stopped. She put her ear to the door. Sniffing inspected the wood, and cold snakes shot through Esteisy’s body. The metal knob turned, and she urinated. She had only a few moments to scale the room and dive through the window.

As she wriggled half her body through the opening, a clamp of knives dug into her calf and she hollered out, kicking her other leg with a mare’s force. Her heel hit something gelatinous, and the clamp of knives let go. Her right shoulder broke the two-meter fall from the window. Sugar-hot blood gushed from her calf as she stood to run, the leg mercifully still intact.

Even as Esteisy cut through the storm, she could hear chirping and screeching from the distancing quarters, the dreadful music of a feast.

Esteisy ran like a madwoman until dawn, following the rising sun. Sobbing from the pain and from what she had just witnessed. Yowling with the ferocity of that which had disturbed her sleep all these weeks, she stopped in the middle of the rainforest and beat a thick birch with her fists, its bark the pale faces of the gringos.

The owner.

Herself.

A now-familiar rustling came from behind Esteisy, and she froze. Her calf throbbed, wanting to flee from her body before being torn apart again. She touched her bruised fingers to the tree as if to use it as a temporary barrier between herself and the monsters.

“Esteisy,” a voice whispered.

It was Luís. She turned around to yell out his name, but he slapped his palm to her mouth, slamming her lips against her teeth. “Quiet,” he hissed.

“They’re close.”

“How did you escape?” she muttered through his hand. “I thought everyone had…”

“Luck,” he answered. “Pure fucking luck that I was born fast. I always get out of these situations unscathed. They call me gato back home—I’ve still got plenty of my seven lives left. Now, we have to get out of here. I promised Victor I’d watch over you.”

Victor’s face cut into Esteisy’s mind like a machete. She bit her already bleeding lip. The taste in her mouth as bitter and rusted as the unearthly possessions she had left there on the coast. The things that only now she longed to return to. That only now seemed manageable.

“I was making my way to the eastern dock,” she said, wiping her eyes. “I was following the sunrise.”

“That’s what I thought, too. Victor was right.”

“About what?”

“He said you were clever.”

Esteisy changed her posture and took the lead, and Luís let her. He avoided asking about her leg, which had now begun to fester. Even she noticed the putrid odor, but they had no time to stop and bandage it. As they snuck through the forest, avoiding dry leaves, crouching low, her mother’s voice distracted her from the pain. In a cool tone, it repeated, “Consider yourself lucky, girl. The most merciful gift this world has to offer is not dying alone.”

“Forgive me,” Esteisy said to Luís.

“For what?”

“For not opening the door.”

“Oh. Look, you don’t have to apologize for that. I understand—”

“I don’t blame you, you know. Not anymore.”

“You don’t?”

“No,” she said, looking back to Luís, who was smiling for the first time in days.

Morning brought the forest back to life. Birds cawed as if no storm had passed, insects circled in wispy clouds. Esteisy and Luís chatted quietly about their lives before the island, their strings of odd jobs, unfaithful lovers, and regrets—Luís touched his heart, and Esteisy, her belly. Luís spoke of fate, and Esteisy repeated her mother’s many sayings.

“Perhaps we’ll live to grow that wise,” he said weakly, his thought breaking at the end. They continued in silence, unconvinced of hope’s pretenses.

Then Esteisy heard the ocean. Seagulls and placid waves after a storm. Perhaps the cargo ship was still there. Perhaps they could make it back home.

Esteisy turned to tell Luís, but a yelp erupted from behind her.

“Run!” Luís’s voice bellowed. “Don’t turn around! Run to the—!”

Snarling answered his call, but Esteisy obeyed him, hurtling through the forest to the dock, dodging low-lying branches and deep, rippling puddles. On either side those creatures stalked her, their pace keeping up with hers. Esteisy knew that at any moment they could pounce and easily ribbon her flesh, but they kept their distance. As if sizing her up. Or, more likely, playing with their food.

The inevitable outcome greeted Esteisy at the dock, its wood wet and soft beneath her feet as she dashed to the very end. Before her, a hundred miles of empty sea opened up, leading all the way back to the coast. The mainland’s purple mountains bloomed in the dawn, and the unearthly possessions she had left behind on the beach stood longing for her unlikely return.

Esteisy knew then what needed to be done. She balled up her fists and bid the final farewell to her home hundreds of miles east, tucked between two sleepy, volcanic peaks. Where her mother would lie for eternity with something missing. A foot. A child. Would her sweet face transform into that of a monster’s? Would she so desperately scour this world and the next for what was taken from her?

Inhaling the last bit of fresh dawn breeze, Esteisy turned to face the beasts whose tapping claws steadily traversed the dock. To fight against what this world, and God, and the gringos had all done. She charged then, her tears warpaint, her wailing turned to battle cries, into the shrieking clamps of knives and their horrible, jutting claws.

As Esteisy gasped out, so too did her mother in her sleep.