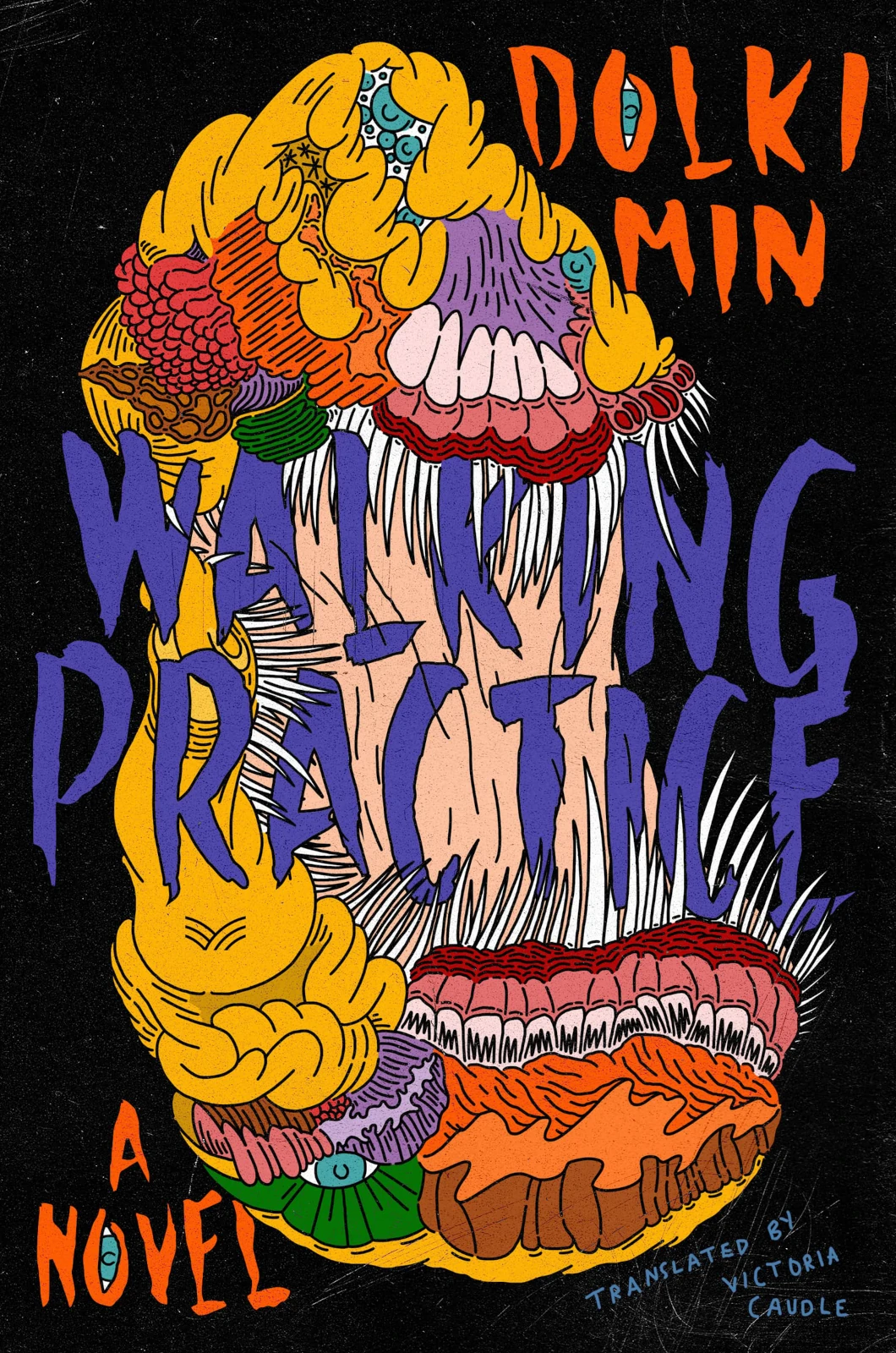

Walking Practice: A Novel by Dolki Min

Words By Haley Lawson

It’s a classic premise: alien crash-lands on Earth and hunts humans to survive. The alien, Mumu, uses dating apps to find their prey. With multiple dating accounts and the ability to transform their physical appearance, they become the ideal specimen for their many one-night stands. At the peak moment of pleasure, they bite off the unsuspecting human’s head. Other than the hair, human is all they can eat. Dolki Min’s Walking Practice, however, takes this trope of aliens killing people and uses it to explore societies’ expectations on gender identities, our relationships with bodies, and what it means to have an insatiable hunger—for touch, for blood, and for love.

Throughout the novel, Mumu addresses the reader, sharing their intimate thoughts. It gives one the feeling of reading a transcript left behind for a shipmate or a salacious diary meant to be found by a past lover. The voice is familiar, quirky, and at times unapologetically ruthless. Mumu brings up gender and identity in the early pages of the novel as Mumu transforms into both male and female shapes to ensnare their victims. They explore the societal expectations of the gender they are mimicking. I loved this aspect of the novel. It added depth and intrigue that made me question my very human existence while connecting deeply with this very alien character. For example, Mumu explores how the gait of a woman takes more thought than a man, even when there isn’t anything physically different. All humans walk on two legs, all humans swing our arms, but Mumu talks about how there is an unspoken difference, a code that signals what we believe our genders are. Suddenly, I’m walking through the grocery store very conscious of how I walk. This book sticks with you, in more than one way.

At the forefront of this novel is the relationship with the body. Gravity, humidity, sweat, sex—all of these have a physicality to them that author Dolki Min examines with excruciatingly beautiful detail. Having spent a year living in South Korea, I could feel the bodies pressing in on Mumu in the crowded subway car with exactitude, the rush of air as the doors opened and people spilled out, and then the stairs leading up to the humid heat of summer. Years later and now living in cold northern Minnesota, I was transported. The strength of the novel is in its sensory details, and I felt it all as if it was yesterday. Like looking through a magnifying glass, this novel explores the nooks and crannies of the everyday experiences our bodies feel. As Mumu painstakingly transforms and travels in a human body, we learn that they hate walking on two legs (their alien form has three) and stairs are a nasty ordeal for them. The struggle Mumu experiences is not glossed over, but dug in. We spend pages on the stairs, no doubt a way to demonstrate just how long it feels to them. We also experience the relief and safety of Mumu’s home, their crashed spaceship in the woods, when they finally let go of the human form and relax into their own body. Throughout these moments, we not only see the physical relationship, constraints, and joys of the human form, but we see the oppression of the binary rules and regulations society holds to. Through this piece of speculative fiction, we can see truths, pain, and harm in the binary limits our societies have.

The novel also uses structure in a unique way, using its chapters to reflect the distance Mumu’s prey is away from them, much like a dating app reveals how far away you are from one another. The heading of each chapter is the distance in kilometers and the further away the one-night stand, the longer the chapter is. Other interesting uses of structure may be somewhat lost in translation. Translator Victoria Caudle explains that what could look like a typesetting error when text is broken apart is an intentional decision. When translating the Korean manuscript, the clusters and characters of Hangul are broken in specific ways that are still legible but can carry multiple meanings. While this isn’t wholly achievable in English, Caudle did her best to demonstrate Mumu’s consciousness changing to something less human. Mumu was so fascinating to me that part of me longed to read the layered meanings so lacking in English. When I learned this aspect of the novel, I was half impressed and half disappointed; still, Caudle manages to create dynamic and interesting tension using Latin letters. In moments of feeding or fear, we visually see Mumu’s thoughts reverted to something more primal, more natural to them. Shorter sentences. Grammatical changes. This thoughtful curation of text ultimately added to my reading experience. Towards the end, as fear and hunger intensifies, the letters are replaced with symbols that are neither Latin or Hangul, but purely hunger. Mumu’s hunger is, after all, what motivates them to leave their home each day, propelling them and the reader through the story. But it’s not just a need for meat or blood—it’s also a deep panging loneliness at the center.

I’ve never experienced anything quite like Walking Practice. While at times it feels haphazard or stitched together, it’s hard to know if that is intentional or happenstance. Mumu reveals new information throughout the novel, often intriguing and thought-provoking, but it did sometimes make me wonder if Dolki Min had just thought of the idea while writing and decided to pop in the new ideas as they came. Still, the voicing of Mumu is distinct and consistent throughout and this made me trust in their journey. I wanted to follow them. I wanted them to be safe, fed, and happy (despite the fact that they could eat any of us if it came down to it). Walking Practice is easily the strangest, queerest, coolest book I’ve read this year.