Undercurrents: An Interview with Justin Hocking

Words By Justin Hocking, Interviewed by Dani Hedlund

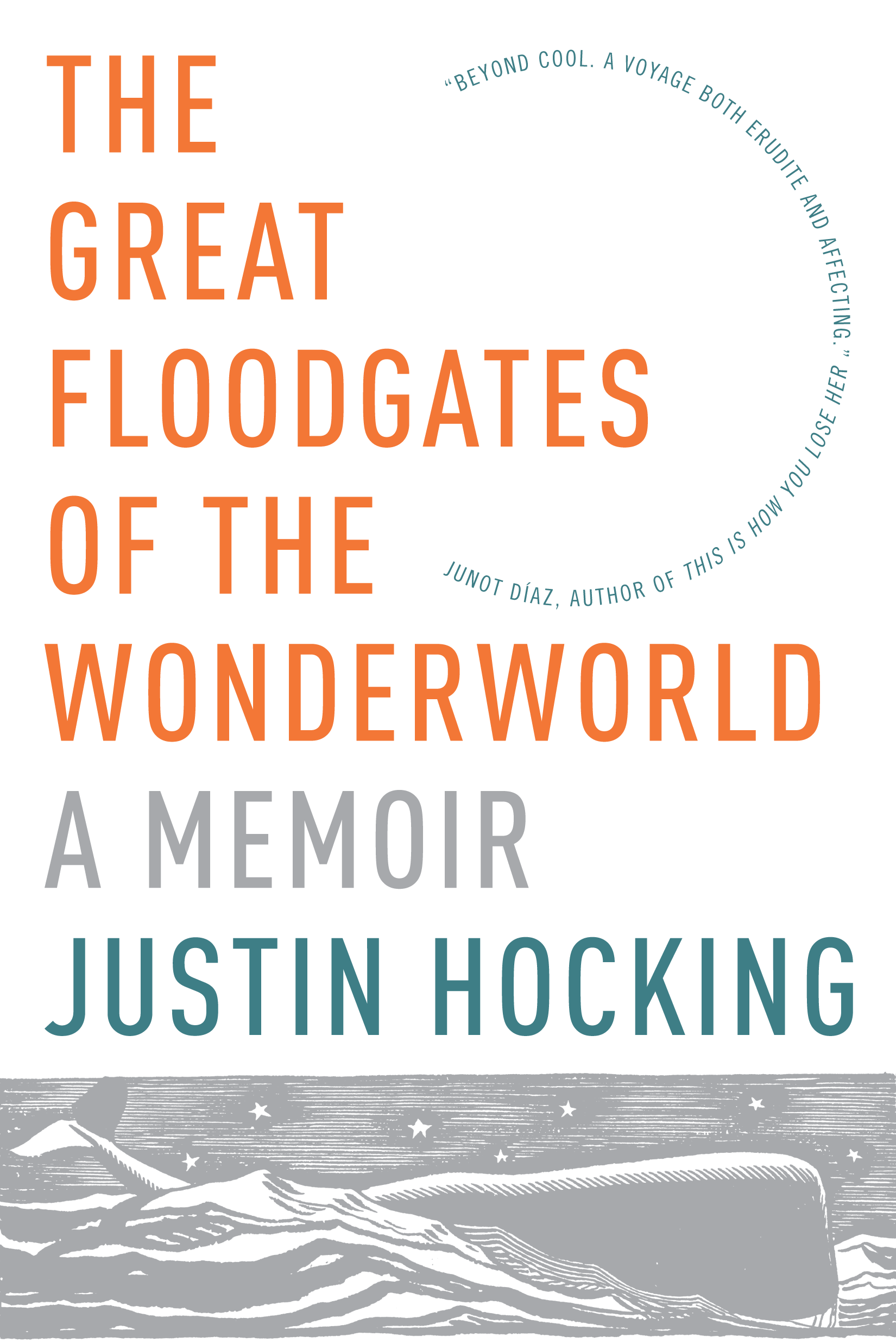

The Great Floodgates of the Wonderworld is a multifarious work. From memoir to cultural analysis, history book to literary theory, and spiritual pilgrimage to political exposé, this book balances an extraordinary number of genres, subjects, themes, and narrative styles. Yet, at its heart, Wonderworld is about a young man finding his place in the world.

Why, as a writer, did you decide that it was necessary to tell “your story” through all these different lenses? Do you think you could have told the same story without these elements?

Well, the memoir was inspired largely by my preoccupation with the life of Herman Melville and the novel Moby-Dick, which is itself densely packed with multiple genres and varied modes of storytelling. It was a kind of postmodern book, before the term “postmodern” even existed—most mid-19th Century readers didn’t know what the hell to make of it, and it wasn’t until seventy or so years later that a wider audience recognized its brilliance. So I didn’t want to just imitate Melville, but I did allow myself to be inspired by his multivalent, digressive, collaged way of spinning a story. Technically, I suppose I could’ve just told my own story, without the other elements. But I think I’ve found my own voice in this braided form of narrative; I’m not sure there’s any going back to traditional, linear storytelling. Not for me.

Given your choice to include all these components, how did you ensure that they didn’t overshadow or distract from the central story? There are many fascinating plot threads—like the adventures of your aunt and uncle—that could have easily been shortened to mere sentences are expanded to dominate a good section of the book.

How did you decide how much of these elements to include?

What I love most about this braided, digressive storytelling style is the way it allows us to dive deeply into our own personal stories, while also weaving in news from the wider world. The story I tell in Wonderworld is deeply personal; I consciously braided in other elements as a way to give the reader some room to breath. I needed to get the reader (and myself) out of my head quite a bit, to avoid this sense of claustrophobia that can sometimes plague a memoir or any first person narrative. But to be honest, when I completed the first draft of the memoir, back in 2011 or 2012, it was over 460 pages. My agent was like, “Yeah, great, you’re on the right path, but there’s no way I can sell a book this long and rambling.” The problem was exactly as you put it: all the digressions and experimentation were overshadowing the central, personal narrative. I’m fortunate to have a great agent and editor, and over the course of a couple years, they helped me tunnel in and chip away at all the extraneous stuff. I excised a good 200 pages or more—anything that felt like it would distract the reader too much from the central emotional trajectory.

Early on in the memoir, you address your obsession with motion, this insurmountable desire—nay, need—to stay in constant motion, either on your skateboard or your surfboard, perhaps in your entire life plan. How does a man so infatuated with speed and adrenaline fall in love with Moby-Dick, one of the densest works of classic literature?

In my estimation, Moby-Dick is one of the most action-packed, page-turning novels ever written, especially in the beginning. There’s a palpable sense of confronting nature in its most raw, dynamic and dangerous manifestation—the ocean—that is just thrilling. I can still pick up the book, flip to a random page, and feel completely transported. On a bit deeper level, Moby-Dick can be read as a monumental confrontation between action and contemplation. Ahab is all action and no contemplation; the First Mate, Starbuck, is the opposite. Ahab’s ceaseless, unthinking action is what brings down the ship. A balanced life requires both action and contemplation. A perfect day for me would be to spend the morning reading and writing, followed by intense physical activity—surfing or skating or swimming with friends—in the afternoon. I also have to admit that I really don’t love surfing or skating for the adrenalin, per se. The practices of surfing and skating are, for me, a way to mitigate the adrenalin and fear. On the best days, you reach a sense of timelessness and flow that have nothing to do with thrill-seeking. It’s more akin to art-making or writing.

Throughout the book, you visit various historical sites tied to Herman Melville’s life—his birthplace, his family estate, the New Bedford Whaling Museum, New York itself. These pilgrimages form narrative markers throughout the book, guiding your own story toward an Ahab-worthy descent or the possibility of salvation on the Rachel.

The visits are beautifully spaced, pulling the reader back into the frame of Moby-Dick at pinnacle intervals, as if each trip were meticulously scheduled at just the precise moment so that—when you did eventually write this memoir—your narrative roadmap would have all the right markers.

How intentional was this? Did you see the makings of this memoir (guided by Melville’s memory) before you began writing it and thus paid extra attention to these foray into the author’s past?

By the time I moved to New York, I’d already done a little writing about my pre-occupation for Moby-Dick. It was in a thinly veiled fiction story entitled “Whaling,” which eventually appeared in the anthology Life and Limb. But I honestly had no plans or intentions about writing a memoir on this subject, not at all. Almost the entire three years in New York, I was working on an entirely unrelated novel. Mostly I was just visiting all the Melville sites out of pure curiosity, and because I felt a little haunted by Melville’s struggles as a writer in New York, but also inspired by the fact that he never gave up, not even decades after the complete commercial failure of Moby-Dick. This period was also the height of the Iraq War, and I felt Moby-Dick had so much to teach us about the abuse of power, revenge, and the lengths America will go to secure our oil interest (whaling was, quite literally, the original “Big Oil” industry.)

After 30 pages of first-person narrative, your reader is shocked to turn to the chapter entitled, “The L Train.” Suddenly, our friendly narrator is replaced by the voice of an inanimate locomotive, speaking to a fictional passenger. Written in traditional theatrical format, the L Train opens a dialogue with the female passenger about a young man who rides on the train—you—and how terrible your fear of traveling under the East River has become.

This is not the only surprising narrative you employ. The entire book is sprinkled with sudden shifts in voice, including the frame of a third-person mental diagnosis and an entire flashback told in second person.

Where did the idea for this unconventional storytelling originate? How did you decided on these narratives specifically? Were there once more like these?

I love the way Walt Whitman, Melville and others incorporated into their narratives all the noise and manifold voices and ceaseless activity of New York City. The “L Train” chapter was my attempt to do the same. While writing this book, I was also thinking very consciously about the issue of narrative distance. This particular chapter chronicles something that’s difficult for me to talk about directly: my struggles with acute anxiety. So I wanted to give the reader, and myself as the writer, a little more distance from the narrator and his problems here. I was also inspired by a 90’s era film, called Naked in New York, in which Eric Stoltz plays a struggling writer who converses periodically with inanimate objects. I like the way it adds an element of the surreal to the narrative.

Writing a memoir is one of the most intrusive, petrifying—perhaps liberating—experiences any artist can undergo, especially if they are exploring a period of their lives when they were struggling. Most of The Great Floodgates of the Wonderworld follows you through the most difficult moments of your life. You have mental breakdowns, suffer from an addiction to relationships, make choices that, frankly, made me want to throttle you. Yet, it is this bravery that makes the book so poignant, that makes the hope of your triumph so dearly desired.

How did you overcome the impulse to “fictionalize,” to use your power of the pen to sugar coat your own downfalls?

I’m glad that you wanted to throttle the narrator at times—I feel the same way! So much of the book was about interrogating my own flaws and shortcomings and poor decisions, especially in relationships. I really wanted to avoid the kind of memoir in which the narrator is continually victimized, but never really examines his/her own small contributions to the world’s misfortunes. This book was, in some ways, a way for me to take personal responsibility. But the process—especially now that it’s out in the world for everyone to read—has been really difficult at times. As David Shields writes, memoir is a genre in which the writer gets their teeth bashed in, so to speak. I think I just tried to tell the truth, on every page. I didn’t worry too much about appearing as a conventional “hero,” but at the same time I tried to consciously avoid hurting the feelings of anyone involved.

No matter how close your life flirts with catastrophe in the memoir, your reader never believes your white whale will drag you under. Certainly, if you are now narrating your story, you must have survived the eminent shipwreck and made it to shore safely. If we are ever truly worried, all we need to do is flip to the book back and read your bio, clearly telling us the results of many of the largest trials in the book.

Did you ever consider revising your bio or acknowledgements to hide the “end of the story” from your readers? Is that one of the reasons that your bio is so brief?

This is an interesting point, and one that I’ve never really thought about, to be honest. The bio is pretty brief, but I guess I could’ve further camouflaged the fact that I ended up in Portland. Hopefully the narrative is compelling enough to still hold the reader’s attention, despite the fact that they know some general details about my current life.

As many of our readers are also writers, I’m always keen to ask our featured writers about their craft. Tell me about your writing process. In Wonderworld you describe mornings hulled up in coffee shops, working on your novel, before an afternoon of surfing. Is this how you wrote your memoir?

I did spend thousands of hours in coffee shops, working on this book. There’s a particular cafe in my Portland neighborhood that has high countertops, where I can work while standing up. Writing is such challenging work; I find that utilizing different processes at different stages is extremely helpful. When drafting early material, I write in short, hour-long bursts, usually first thing in the morning. I also carry a small notebook around to jot down notes. I can work for longer periods of time once I transpose my handwritten first drafts onto the computer. During this phase, I need a lot of silence and solitude, because you never know what kinds of creative gifts you might receive if you’re paying close attention. Oddly, the gifts often arrive when you take a short break from the work, to make a sandwich or take a shower or go for a long walk. The moments when you have to drop what you’re doing and rush back to your computer to get a new idea or bit of dialogue down—those are what I live for as a writer. During the more advanced drafting and editing phases, I can write for hours and hours at a time. I was fortunate to spend a two-week writing residency at Sitka Center for Art and Ecology, where I worked ten or more hours a day to finish a first complete draft. It was arduous but exhilarating work.

Also, specific to this genre, how did you ensure that you were accurately depicting the events in your life? Did you keep journals of your time in New York? Did you spend countless hours on the phone with your old flat mates, taking notes as they recalled memories of your melancholy years?

I was certainly concerned with presenting an accurate portrayal. I spent hours and hours on the phone with my uncle, making sure I’d gotten down correctly the details of his exploits at sea, and his falling out with the Scientologists. I also write copiously and obsessively in journals; I mined those for quite a lot of material. I’m still close with my old flat mates from New York, but I didn’t really consult with them. As memoirists, we need to have fidelity to the truth and accuracy of details; I think it’s immoral and stupid to grossly fabricate the details of your life, as writers like James Frey did in A Million Little Pieces. On the other hand, we’re writing creative nonfiction, not journalism, and we’re drawing on memories, which are invariably fallible, so I do think there’s room for a certain amount of embellishment, especially when recreating dialogue that took place a decade ago. To me, this is all in service of striving toward the emotional truth of what happened.

Now that you’ve successfully published two books, what advice do you have for new writers trying to break into the industry?

I won’t sugarcoat the fact that it’s very difficult to break into the commercial publishing industry. However, in many ways, there’s never been a better time to be a writer. What I encourage my writing students to do is this: make the best work you can, and then play the publishing field at every level possible. Self-publishing does not have the stigma it used to—especially when you’re talking about zines, chapbooks, e-books, etc. Long before I got a book deal, I actually self-published an excerpt of Wonderworld, in a small chapbook with a letterpress cover. It was nice to have a physical chunk of the book out in the world, to begin the process of connecting with readers. Learning the traditional art of letterpress printing was fun and empowering. I think it’s increasingly important that writers learn some basic graphic design and layout skills, such as Adobe InDesign and Illustrator. I’m also intrigued by the possibilities for new modes of storytelling via social media, digital publications, as well as the possibilities for crowd funding via sites like Kickstarter.

While writing my memoir, I also sent individual chapters out for publication at literary journals. Of course, I got a ton of rejections. Fortunately, a great California-based journal named the The Normal School published a chapter called “All I Need is This Thermos.” In a stroke of amazing luck, a literary agent read this particular issue of The Normal School, and contacted me about developing it into a book. So you just have to put yourself out there; if you’re not getting consistently rejected, you’re not submitting enough.

Last but not least—yes, I promise I’ll stop after this one—what is the next step for you? Are you planning to finish the novel you were working on while you were in New York? Are you going to toss your pen away and spend the rest of your life on your surfboard? Will you start constructing the museum for the oil industry you so brilliantly hypothesized in your book (because I will definitely want to visit…perhaps just for the regal paintings of Dick Cheney hanging over a miniature oil rig)?

After running a small arts nonprofit for eight years, I’m transitioning out of the Executive Director role to make more time for my writing and teaching. I’m excited to work on some short articles and essays, but I also have a few more major projects on deck. I’m drafting a new, long-form nonfiction piece—possibly another memoir or essay collection—that goes further back into my childhood and early adult years. A short story collection is also in the works, plus a possible novel idea (although it’s completely different from the novel I was working on in New York). I’m also excited to continue teaching in two programs I helped launch: The Certificate Program in Creative Writing and Independent Publishing via the IPRC, and a new Wilderness Writing concentration in the Low Residency MFA program at Eastern Oregon University.