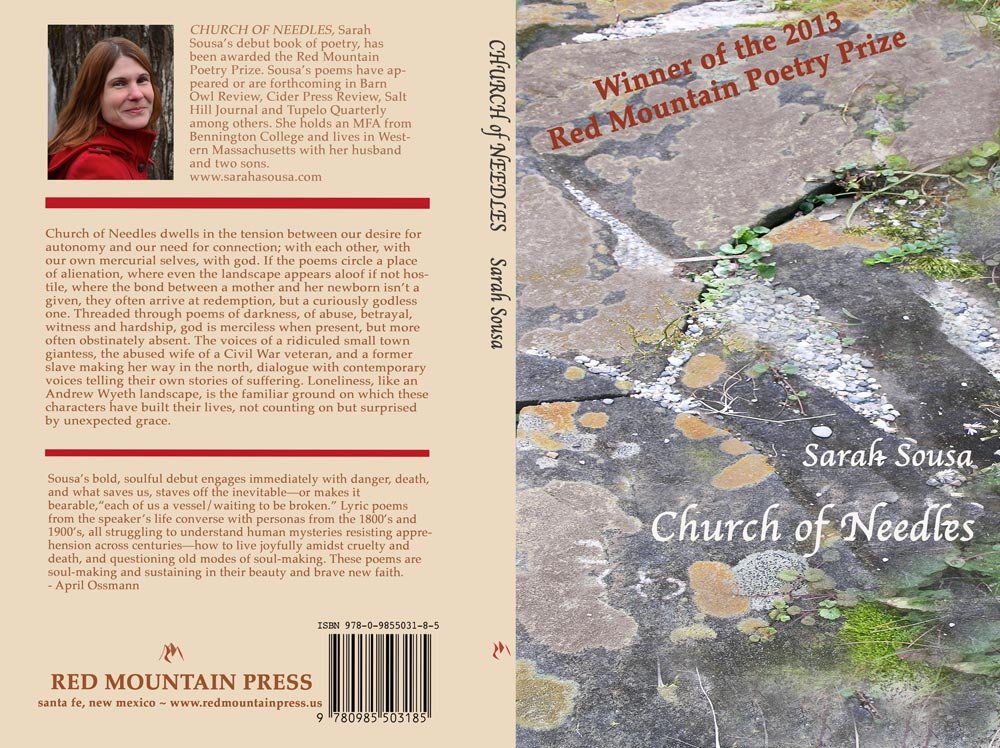

Truth from Blasphemy: An Interview with Sarah Sousa

Words By Alison Auger

Church of Needles is an astounding collection of poetry that recollects the Civil War, childbirth, the uncertainty of motherhood, and a re-imagining of the relationship we have with the world around us. At the heart of this collection is a desire for unity and meaning in the world, despite an inherent lack of connection.

NOTE: This interview was recorded by phone, so any errors should be attributed to a less-than-reliable connection. Enjoy!

What first inspired you to write poetry, and later a book of poetry?

I don’t know originally why I started writing poetry; I know I started fairly young. I read a lot of Emily Dickinson and I loved the power of her voice and the power she achieved through poetry, and I think I always wanted to achieve that power. It’s kind of a quiet power but it was definitely evident.

Now I am inspired by all things history: vintage photos, diaries, letters, and extinction. What inspired me to write the book? I think it’s a culmination for every poet. I had a lot of collected poems but nothing that came together so I went to start my Master’s degree in writing at Bennington College where the goal of the program was to write the book.

You’ll see different subject matters throughout that book because of how long it took to put it together. For example, in 2007 I found an antique diary that I used to inspire an entire section of the book.

Can you describe the process of putting this book together?

Church of Needles was my first collection, so it was different from putting together the second, which is coming out this fall. The experience of putting this first one together was a little bit haphazard. Many of the poems were written during the MFA program at Bennington, though some predated that.

It also did undergo several transformations during the 4 ½ years after I graduated, submitting to contests and different publishers. I tried to tighten it, cut and added parts I never thought I would—it is kind of a challenge to put a book together because you want your strongest poems in there but they have to hang together and create a larger story.

It was in this process of editing that some of the themes of motherhood, mortality, and spirituality/religion emerged. I’m not a religious person, but I do address God and that…issue. Also, the book became very tied to landscape. I was living in Maine when I wrote most of the poems and was in Maine most of my adult life, though I grew up in Massachusetts. But I was always on a New England landscape. When I was living in Maine, I had farm animals, and lived in a small cabin (without electricity at one point), so it was very costal land, very hard-scrabble and sort of like it was for most of its history.

The historic poems about the diarist and other poems about figures from the 1800s also deal with the hardships of the land, and those ended up kind of meshing with more contemporary poems in the book.

What do you try to achieve with your poetry? What makes good poetry?

You know when you’re writing it what you feel is right. Some poets call it the heat in writing and you go towards that. You figure out when you’re writing what’s working. So I think for me identifying truth, some nugget of truth in things—you know when something is ringing true, and that you’re getting deeper than just surface descriptions of something, of an event, or a feeling. You’re hitting the truth-nerve, if there is such a thing. And a lot of that comes out without your cooperation, sometimes. You just sit down and get into it and things will kind of pop out at you. I think that’s what I go for.

That also goes for when I’m reading. I enjoy playing with language, I enjoy leaps in poetry, and when you’re not quite sure what’s coming next—when it’s not following a straight line. It’s hard to put your finger on, but you know when you can see it.

What are some of these “truth nuggets” that you find yourself uncovering in this collection?

I think “The Art of Flying” would be the best example. The last lines in that poem: “that earth is a myth created by birds that would kill for a rest”. I didn’t work for that. I was working on a poem and then that kind of popped in and I knew it was perfect for the end. It has a sort of torque, you know? It’s like, birds creating the death of these humans who want to fly but needing the earth to land on because they don’t want to keep flying all the time. There are deeper things there, but there was just something that I knew was truthful in that.

Another example: there’s a newer poem that I’ve been working on for the next collection about women stitching. And on the surface it’s them stitching quilts and exchanging certain stitch techniques like the fan-wheel stitch, or the lover’s knot—but there’s kind of an undercurrent in it of women stitching each other from injury (actual physical injury or metaphysical). And in the last line I say “they make beautiful scars.” I had been thinking and reading about genital mutilation, which happens a lot in other countries, and learned that other women performed it. I felt really conflicted because I was working on this poem at the time and I was trying to get across this idea that women are healers but they can also be destroyers and injurers at the same time. And so how truthful would I be if I don’t acknowledge both sides? And so I left it alone and ignored it for a little while and then that last line just came to me and it was perfect because it gets at that idea that the act of stitching something creates a scar—it both heals and mutilates at the same time.

Is this poem going to be in the next book? Will we get to read it soon?

No, that won’t be in the next book. That was kind of a one-off, but I did include it in a chapbook manuscript that I sent out a few times. They’re very women- and girl-centric poems.

Right now it is floating around in the prize circuit. I’ve sent it out to a few publishers but so far, nothing. I have a problem with chapbooks because I always want to make more out of them! And I may go on to make it something bigger.

Back to your current book: it has been described as being “absent of god,” even though there is a tone that calls for unity and meaning. And you even described one of your major themes being spirituality, even though you aren’t religious. Could you speak more about that?

I didn’t really grow up religiously. I mean I was a Sunday school teacher for a little while but… I think the reason why God is absent in a lot of the poems is that that’s how I experienced God. You know, a yearning for someone to be on the other side to offer a little help, yet no one seems to be there. In prayer I always felt like I was being thrown back on myself—like it was kind of a cruel joke. So that’s something that I definitely felt and came out in the poems, this sense of reaching and trying to find that connection and not really finding it.

And yet, I feel like I’m kind of a mystical type of “believer.” I definitely believe in mysteries but I don’t think I want them all solved. I think I like that there’s a mystery in there and I like to poke at it.

I think of Emily Dickenson when I think of my own “belief” because she was taught at a religious school and was surrounded by people who were accepting faith and she couldn’t. She made some comment about how she would like to believe, but she just can’t. And I think that I am the same way—I can’t just accept something and go with it, I always have to question and question.

So poetry is very spiritual for me because I can poke and question but it’s not something that I have to accept and understand. But it feels spiritual because I can just write and write and things come to my mind and I just don’t know where they came from, and so I feel like it’s a kind of connection.

Sometimes I feel that we’re all talking the same language—religion, spirituality, artists and our process.

I think many people would agree that the act of writing or creating art is a kind of reaching for connection.

Definitely! And it’s really all artists I think. It’s all just finding that truth and making connections. And you know I think it’s connecting with your viewer or your reader that’s hard about writing.

To speak more technically about your writing, how do you find yourself structuring and pacing your poems? Many novice writers set out to write about a certain thing or an idea and get stuck on surface level or not fleshing out their thoughts enough. So what would you be your advice to new writers on how to create good poetry?

I totally know that feeling. New writers (all writers, really) have something to say and they want to get that across but a good writer is willing to be open to the process and allow things to change as you write. So while you’re writing and re-writing and editing, you find new meaning and end up going deeper than your first thought.

So my advice to aspiring poets would be: keep writing, keep experimenting with your voice and your style. Find out what your strengths are. Sometimes what people might tell you is a weakness you find is something that is peculiar to you and you can capitalize on that. You should read a lot of poetry—both classics and contemporary. And also, just be creative when you write! People in other mediums still play with their work and I think that especially because poetry has such a reputation for being stiff that you need to be playful with your work. Writers, especially new writers, get intimidated thinking that poetry is very serious business, and that can kill the whole creative process.

People also tend to hate revision—think it’s an evil, creatively destructive monster—but really it is important and can be just as creative a process as the first draft. I myself have come to really love revision. At a certain point, everyone knows their strong and weak spots and you just have to accept those in order to revise and improve.

I had to learn that during my undergraduate years. I got a poem back with red ink all over it, saying, “fix this” or “make this better,” and I honestly didn’t know what that meant or what to do. So be willing to both accept advice but also not accept advice. Once you reach a certain level of writing it becomes someone else’s opinion about your work that may not be necessary. You have to learn what you think is relevant advice about the poem and not take what you don’t think is relevant. When you’re in a workshop class with ten different people who all want to change one little thing you can’t take all their advice because then it wouldn’t be your poem anymore.

In TBL’s last quarterly issue, we republished three of your poems from this collection, “The Art of Flying,” “Scrying,” and “Lullaby.” Since they all seem to have such a personal feel, could you tell us more about them?

The most “from life” piece in that group is “Lullaby.” It was pretty much about the birth of my first son and how a mother can be more than just the nurturer, but also someone who could be dangerous. A lot of power rests in her hands.

“Art of Flying” I’ve already talked a little about. “Scrying” was interesting because it was kind of a mix of real and historic things. Part of it is based on where I live now and the barn that is on our property. The barn has lots of writing inside from the early 1800s, so they have things written about how many bushels were picked one year and of course the kids would write down their names and the dates and such. So I used that, I put character’s names from the antique diary and put their names on the wall for the poem. I think I took a lot of poetic license with that one. But that poem was generally about my obsession with history. It reflects the sad fact that history is more than I’ll ever understand, so I added voices and characters and half-truths that brought me closer to the real truth of all this leftover history.

At TBL we talk a lot about book publishing and story publishing, but what is it like to get poetry published? How does someone go about publishing a book of poetry?

Well, from when I first put the book together (right before I got my master’s degree) it took about four and a half years before Red Mountain Press picked it up. And before they did I sent it to dozens and dozens of contests I didn’t even keep track of. It’s such a heartbreaking process because it takes so long. This book was especially difficult because it went on to become a finalist for a number of pretty prestigious book prizes, but never won. You send it out in September and no one even gets back to you until March. So you end up sending it out everywhere you can think of and when it comes back and you get close…

I remember at least half a dozen times just crying when I get the rejection letter back saying how close I had come and just thinking, this is never going to happen. On top of that, I’m 41 and I’m just now publishing a book. To me that’s really late, because I’ve been writing all my life, since I was really young and writing seriously since I was in my early twenties.

I think what helps me the most (and I’m about to talk about first books on a panel at the Berkshire Women’s Writer’s Festival in March) was moving on to a different project. It was wonderful–it just took all my attention away from the rejection and allowed me to move on from those heartbreaking years of coming close but never making it. It also allowed me to grow, because after those four and a half years of editing and submitting I learned how to put a book together. The project I moved on to while I was submitting Church of Needles actually got picked up really quickly—in fact in about three and a half months of submitting instead of years.