To Write the Other, Find Yourself

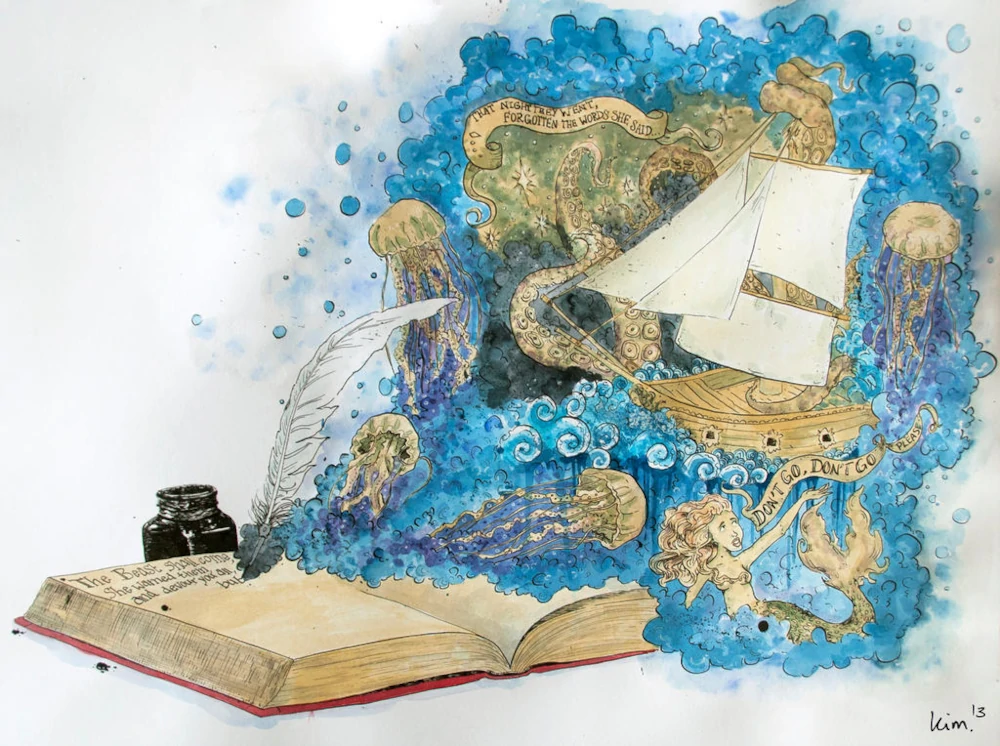

Words By Corinne Guichard, Art By KiDa90

There are lots of people you aren’t. In fact, there isn’t a single person out there who you are, aside from yourself. And all those billions of people out there who aren’t you have bodies and memories and romantic preferences and music tastes that are unknown to you. No matter how much you research or converse, you’ll never fully understand the infinitely nuanced existence of another person.

But still, we try. We study other cultures and ask our neighbors about their childhoods; we gather fun facts and shared experiences and use them to construct an entire person in our mind. These people, these fundamentally incomprehensible beings, are sometimes referred to as “the other.” Often, we want to write about the other. But before we can successfully write about the other, we need to figure out a whole hell of a lot about ourselves.

First, let’s make this distinction a little clearer: who is the other and who is the self? For our purposes, we’ll say that “the other” is anyone who hasn’t experienced life quite like you have. There are some obvious differences—race, religion, gender identity, class, ability, etc.—that cause someone’s culture to be different than your own. But by no means does someone need to differ from you in all of these aspects to be other. Even one or two seemingly minute differences can cause a person to exist within a culture that is foreign to you.

“The self,” on the other hand, is you. But it’s not just you. It’s those whose culture aligns with your own, whose life experiences you can comprehend based upon your own life. If you’re a white agnostic woman from California writing a fictional account of a white agnostic woman from Oregon, for example, you are probably writing the self, even though your character isn’t really you. If you write about a white Mormon woman on a mission in the Philippines, on the other hand, her culture and world ideals will likely be vastly different than your own. Even though you share a race and gender with your character, the differences in her culture cause her to be other.

There’s a lot of debate about whether people should write about the other or stick to the self. To me, this is a thought-provoking but misguided question; both are inevitable and interwoven. As we write about the self, we will likely encounter or create characters who have different backgrounds than us. And as we write about the other, every thought and moment will be filtered through the perspective of ourselves. When we write about others in this way, we are really illustrating our own perspectives and (

1. You are connected to the other.

Cultures exist within an interconnected web of societies and peoples. They feed off and influence each other; elements of one culture may be apparent in another culture that is geographically and theologically distanced from it. Individual cultures, then, are less of a series of rooms with locked doors than a cluster of interconnected lakes. Especially with international transportation and worldwide media, aspects of different cultures are constantly drifting to others, causing them to become intertwined. Your own culture’s connection to the other inevitably affects your perception (and in turn portrayal) of it. The connection may overly romanticize—such as America’s obsession with Native American dreamcatchers and headdresses—or unfairly condemn—such as the portrayal of Middle Eastern people as terrorists. The aspects of the other that have drifted to your culture may be limited, and you likely have preconceived notions and stereotypical ideas about them—admit to and address these biases, then try to move beyond them.

2. Your privilege is different.

If you’re reading this on a computer, tablet, or smartphone, you are more privileged than many, regardless of whether you’re more or less privileged than the character you want to write about. More often than not, the other is underrepresented—which comes largely from the fact that the literary industry is and always has been dominated by white men. Every character has a relationship

3. You are the other, too.

To most people, anyway. This is important to avoid depicting characters as stereotypes and caricatures of the group they belong to: You are extremely complex, so your characters should be, too. All of your individual traits in context are, in fact, what

4. There’s a reason you chose to write about this.

Some real-life thing has compelled you to tell a story through the eyes or experiences of another. How does this thing, this catalyst, influence what you think, feel, and write about the other? What strife is bubbling within you that makes you feel like you should write this story? Is it this character—do you need to share them with your readers? Do you love them, or hate them? Or is it the story itself—are you so engulfed in bringing a certain idea or message to life that you will do it all costs, including taking pains to write about someone who is not you? If your motivations have an agenda other than to tell a truthful story, you might want to reconsider your choice.

5. You can do good.

Writing about the other can increase empathy, both in yourself and in your reader. You can try to better understand those who aren’t being talked about or tell a different story about those who are. Even when the others about which you are writing have many of their own voices talking, your voice can contribute by providing a unique perspective. Of course, writing about the other isn’t about doing anyone a favor or being a savior to a less privileged culture. It’s about telling true stories and being authentic in your representation. So many stories are by white men about white men, which is not at all indicative of the diversity of people reading, writing, and existing in the world. Writing about a culture other than your own in a respectful, thorough way can reveal truths about both the other and the self.

7. You can do bad.

On the other hand, writing about the other can further ostracize marginalized groups and perpetuate stereotypes. Historically, the process of othering has been used to stereotype and emphasize differences of a certain group of people in a manner that makes them seem inferior. When Asian characters are consistently portrayed as nerdy, goofy sidekicks, or women characters are depicted as overly sensitive and bad at sports, for example, entire groups of people seem abnormal and different in inaccurate ways. As a writer, misrepresenting a group of people almost certainly is not your intention. But it’s possible to do this unintentionally, by generalizing and focusing primarily on the otherness of the character. Again, remember that your character is more than that—they are an individual, and it’s crucial to represent them as such.

It is also possible that you will, simply, screw up. Even if you do everything you can to embody someone else and paint a full, complex picture of their life, you may not get every detail correct. You may misrepresent something, or depict microaggressions that are unintentionally discriminatory or offensive. So many actions, statements, or incidents that seem innocent and acceptable to us can feel hurtful or ignorant to others, and something you write could inadvertently cause offense. That doesn’t mean you should stop writing about the other; instead, do everything you can to enter the mind and life of your character. Intention—coming from a place of sincere empathy—is crucial, but not enough. Research and strive to understand the cultures that you are writing about. When you mess up, challenge yourself to do it better next time.

8. You can do better.

It’s a process—writing the other, writing the self, all of it. You probably won’t get it right the first time. But with