The World of We: An Interview with Justin Torres

Words By Justin Torres, Interviewed by Dani Hedlund

Please note that this interview was originally published on our old website in 2015, before our parent nonprofit—then called Tethered by Letters (TBL)—had rebranded as Brink Literacy Project. In the interest of accuracy we have retained the original wording of the interview.

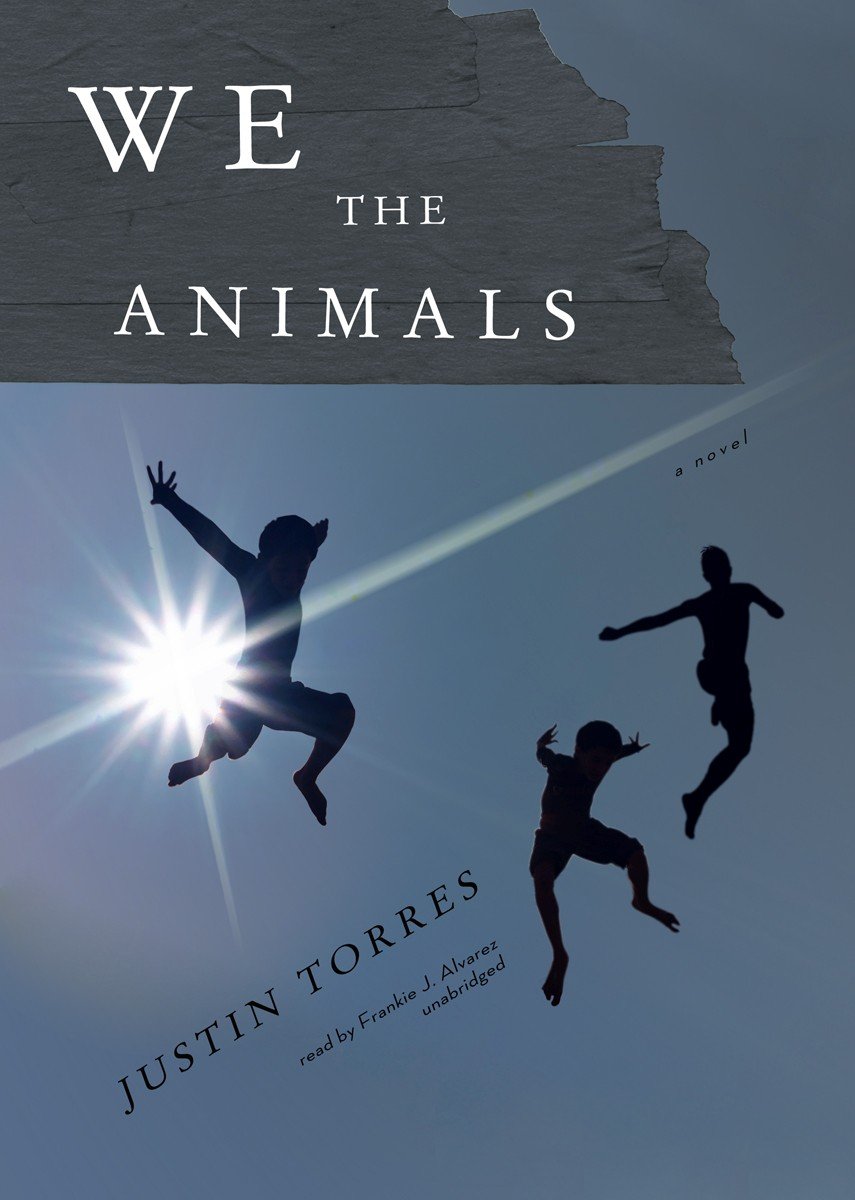

With a narrative as alive and dynamic as the characters it describes, We the Animals is a shocking, dark, and courageous story of three brothers wrestling their way into adulthood. Justin Torres’s debut novel fictionalizes his own turbulent upbringing, introducing us to a young couple unprepared for children and the three boys battling to understand their parents’ mysterious struggles. Through a series of insightful and beautifully written vignettes, Torres invites us to witness both the love that binds their family together and the desperation that threatens to tear it apart.

As the novel opens, our six-year-old narrator, the youngest of the brothers, pulls us into their world of “we,” a world where boyish desires consume their every thought and action. They want to eat more, play more, sleep more. Nothing exists for them apart from these wants. They want their father to stay, their mother to smile, they want to fly away like their trash-bag kites caught in the wind. But more than anything, they want to stay together, to always be “we the brothers.” This, however, is a fate that cannot materialize, for as they grow up, they also begin to grow apart, the distance between their own lives and the confusing adult world rapidly evaporating.

Our narrator, in particular, begins to change, realizing that there is no room inside the world of “we” for his emerging identity as “I.” As the bracing events of the plot pull the narrator farther away from his family, so, too, does the narrative distance itself from the elements of the plot. The struggles of their near-poverty existence no longer bring them closer together, but now threaten to pull them apart. The final vignettes are reported from the outside, each impersonal word reminding us of the familial connection that has been lost.

As the book approaches its close, the same narrative that had so warmly welcomed us in now traps us, holding us down as it forces us to observe outcomes both heartbreaking and horribly ill-fated. Yet, even through the darkest, most violent sections of the novel, the original openness to the grace and love of their family is never destroyed. Even when we turn the last page, it is with this same wonder that we hope they all find a way to escape, together, the many I’s united in a world of we.

Torres on We the Animals

We the Animals is a novel inspired by Torres’ own life. When I asked him why he chose to fictionalize his story instead of writing a memoir, he explained that “the poetic language, rhythm, and imagery” of fiction allowed him to access an emotional truth that would not have been as profound otherwise. By breaking away from the constraints of reality, Torres explained, he could also make myth out of his characters, creating individuals like Paps, a man who is not only the boys’ father, but also the concept of the Father. This “universalized character” is able to tear down the barriers between the fictional family’s experiences and the readers’.

Torres also described how the “absolute freedom” of fiction also allowed him to break away from the adult vocabulary used to describe elements of his upbringing. Instead of applying clinical terms to the plot elements like “dysfunctional family” or “abusive relationships,” Torres envisions the story through the questioning eyes of a child. As Torres explained, “this family, they love each other, you know, and they’re doing what they’re doing based on the pressures of their circumstances…but children don’t think in terms of function or dysfunction. They just experience what is put in front of them and they’re open to it.” Torres went on to explain how, when these children become adults, people try to diagnosis their pasts, making them ashamed of their experiences growing up. Intentionally combating this, he created a narrative in We the Animals that “is wide open to the violence and the grace of all of it,” allowing us as readers to see past the clinic diagnoses and see the same love and wonder as his narrator.

This discussion of manipulating perceptions in the novel pushed us next toward ideas of form. Impressed, of course, by the incredible evolution of the narrative, I was eager to discuss the structure of We the Animals’ with Torres. After gushing for an embarrassing amount of time about how the rhythm, pacing, and language so beautifully reflects the content, Torres began to laugh—a reaction I instantly feared—but then he saved me by declaring, “I’m so glad you noticed that!” Excitedly, he explained that he put an enormous amount of effort into having the form mimic the internal themes and plot developments. When questions of the ending arose, Torres said that while he had always planned to gradually transition from “we” to “I,” he did not originally intend to switch narrative persons: “I knew the ending was going to be wildly structurally different. I wanted it to come as a sort of shock because I was writing against this traditional arch of the coming-of-age story.” Instead of having a gradual progression, Torres wanted the form to reflect life in the way that “shit just keeps coming at you and then one day, boom, you’re out into the world and there’s this kind of an ejection from the family.” When he discovered, with the sudden introduction of third-person, that he could “have the structure mimic everything on the level of content,” he admits that he was ecstatic. “I’m really happy with what I came up with,” he concluded with a shrug, unable to repress another wide grin.

Finally, I asked Torres how he was handling the sudden success of We the Animals. Shaking his head in disbelief, he replied: “It’s been a dream. I don’t think anyone expected it to be accepted so widely and so well. It’s dizzying and I’m enjoying it, but I’m racing to catch up with it!” I pointed out that I see his book everywhere—NPR, Barnes and Nobel’s “Discover Great New Writers,” Amazon’s top picks. Torres laughed: “I know, right? It’s like I’m hiding under your bed!” But in all seriousness, he confessed that the success is “absolutely amazing,” but that it, surprisingly, isn’t the best part. Torres shared with me stories of readers coming up to him, telling him how much his work has touched and inspired them: “That’s enough for a lifetime,” he declared, “and that’s what I write for.”

Torres on Writing

When I asked Torres what his writing process is like, he immediately answered with one word: “slow.” After a soft laugh, he elaborated: “It was really slow going. I mean, I’m a really deliberate writer; every word I write is considered and precise. It takes forever…some writers can sit down and write for eight hours and then go back and revise, but I’m not like that and I don’t think I’ll ever be.”

Not all of his time “writing,” he admitted, is spent before his keyboard. When he isn’t distracting himself from work by “turning on music and dancing around [his] house for hours,” he spends a great deal of time intentionally finding other uses of his time, explaining that it really helps him “to walk around with the story inside [his] head for a while, trying to memorize as much of it as possible before [he] sits down to write.” This process aids Torres in eliminating a lot of the “fat,” and he figures that if it sticks in his memory, “there must be something right about it…on the level of rhythm and rhyme and also content and meaning.”

Eager to acquire writing tips for our TBL members, I asked Torres what advice he could give to aspiring novelists and poets. Instantly, his head began to shake, hands popping up as if trying to push the question away. “I’m not in the position to give advice. I just got struck by lightning.” I tried to protest, calling upon both the brilliance of his prose and the wonderful success it has enjoyed, but Torres cut me off with a laugh. “Trust me, if you met me five years ago [when I started writing We the Animals], you would not ask me for advice. I was a wreck.” But after a few minutes, we began talking about the length of his novel, and he told me the story of how many literary-minded people insisted that he should expand the book to the traditional three-hundred page range, and, against his intuition, he added a secondary narrative to the book which he admitted was “terrible.” After another laugh, he added, “I’ll never let anyone see it…and I’ll never let anyone ever convince me to do that again.”

As the interview neared its close, he added—after many precursors about how he “wasn’t advising anything”—that he stuck as much as possible with his intuition in the writing of We the Animals, and he tries to get feedback from dependable readers around him, always striving to write something that couldn’t be ignored. “I trusted myself in that sense and, well, if that approach can be taken as advice, so be it.”

Excerpt from We the Animals

When we were brothers, we were Musketeers.

“Three for all! And free for all!” we shouted and stabbed at each other with forks.

We were monsters—Frankenstein, the bride of Frankenstein, the baby of Frankenstein. We fashioned slingshots out of butter knives and rubber bands, crouched under cars, and flung pebbles at white women—we were the Three Bears, taking revenge on Goldilocks for our missing porridge.

The magic of God is three.

We were the magic of God.

Many was the Father, Joel the Son, and I the Holy Spirit. The Father tied the Son to the basketball post and whipped him with switches while the Son asked, “Why, Paps, why?”

And the Holy Spirit? The Holy Spirit hovered and had to watch—there and not there—waiting for a new game.

When we were three together, we spoke in unison, one voice for all, our cave language.

“Us hungry,” we said to Ma when she finally came through the door.

“Us burglars,” we said to Paps the time he caught us on the roof, getting ready to rappel—and later, when Paps had us on the ground and was laying into Manny, I whispered to Joel, “Us scared,” and Joel nodded his chin toward Paps, who was unfastening his belt, and whispered back, “Us fucked.”