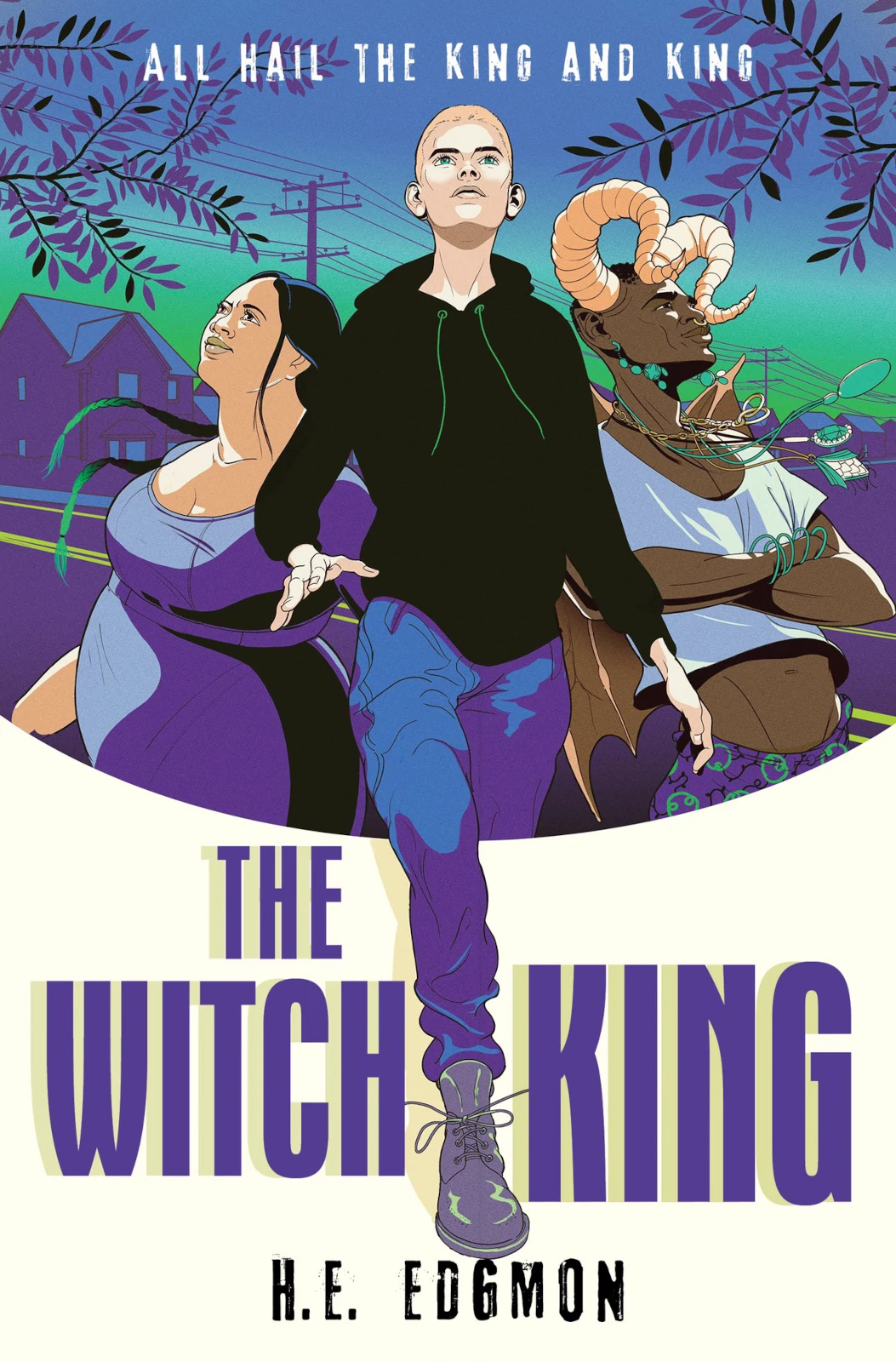

The Witch King : An Interview with H.E. Edgmon

Words By H.E. Edgmon, Interviewed by Dani Hedlund

I’ll open with the single most cliché thing: what inspired The Witch King?

The big factor that pushed me to finally write this book was fanfiction. I have multiple marginalized identities that take place at different intersections, and when I grew up, I never saw myself reflected in mainstream media, whether that was published books or TV shows. So, I retreated into fandoms for a big part of my life. In fanfiction, characters can be whatever you decide they are. I’d always known I wanted to be a writer, but I was trying very hard to write stories that I felt would be more mainstream, which means writing only cis characters, and they didn’t really reflect the people in my circle or who I really was.

Finally, one day I said, I’m going to tell a story that feels authentic to me because I want to make people feel the way that fanfiction allowed me to feel, which included reclaiming the tropes that had been denied to us in mainstream media and seeing ourselves as the main characters.

Can you talk to me about your worldbuilding? You tap into a bunch of interesting genres, and you have so much worldbuilding around the monarchy and how the magic works. Where did each of those pieces come from?

I’ve always been super interested in pocket worlds, which are worlds that exist alongside but separate from ours. A popular example is Narnia. You step into this doorway, and you’re in a wildly separate place. I’ve always been fascinated by this idea that there are hundreds or thousands of pocket worlds, and these creatures can come in and out of these worlds through doors. That was the basis for my worldbuilding, this pocket world, and what would happen if the creatures that were over there stepped through and came here. As for the fae, when I went into the book, I had not read a ton of works about them, so I asked myself what do I find most compelling about magical races? I basically built my own dream monsters.

I loved your note at the beginning of the book, where you talk about this brutal honesty in the way you wrote it. What was that experience like, tearing off all the band-aids and saying this is what I’m going to write, directly from the heart?

I grew up in the very rural, very conservative Deep South. I had known I was queer and trans as far back as I can remember, but I was also surrounded by very conservative ideals. In my childhood, I never saw anyone like me because typically people like me get out of the very deep conservative pockets of the South as quickly as they can. I didn’t know I could be the person I am and have a happy life. I spent a big chunk of my life trying to turn into someone who I thought was more deserving, instead of creating the happiest, most authentic version of myself. That did not work; it was painful and uncomfortable, and I was very unhappy. Eventually, well into my twenties, I realized, largely thanks to online trans communities and friends I made as an adult, that it was entirely possible to be the most authentic version of myself.

Since writing the first draft of this book, I have come out publicly, and that has been kind of a brutal process. It was as brutal as I thought it would be. I did lose people in that process, but I am going to keep creating this happy future for myself. I think that it’s important for this book and books like it to exist with these characters at the forefront who create their own happiness. I want kids who are like me, who are a generation behind me and a generation behind that one, to know much earlier than I did that this happiness is totally achievable for their most authentic self.

I think that’s wonderful. One thing I found really striking was just how funny the narrative is. You’ll be in the middle of an incredibly dramatic point and then there are these weird jokes that felt authentic to how someone’s mind would actually process something like their magical ex-husband breaking in on them. Was that natural to the way you speak and think, or did you try to imbibe that bit of humor?

Dialogue has always been something I’ve considered to be one of my strong suits. Here’s some advice for anyone, particularly people who are writing YA novels right now and tapping into that Gen-Z-type humor: TikTok. Listen to how teenagers talk to each other because the jokes are there, and they are hilarious. Their sense of humor has shaped my sense of humor and the humor of the book.

The Witch King is a beautiful fantasy, with powerful statements about gender, identity, and how society thrusts things on us, and how we rebel. Those are really adult topics. Did you ever feel there was anything you weren’t able to write because of the YA genre? Did you have to hold back anything that you would have put in an adult book but felt you couldn’t put in this?

Honestly, no. The way you approach certain topics is different because you are presenting them to teenagers, but I don’t think there is anything you can’t discuss in a YA book. For anything that can happen, there is definitely a teenager out there who has experienced it, who is going through it, whether that’s a good thing or not. In talking about what some people try to “dumb down” in YA, I’ve observed it’s often political in nature. Way back before I agented, long before I had a book deal—when I was first getting feedback on my manuscript—I had somebody say to me that the character Briar, who is very involved in political activism, was very unrealistic for a teenager. I don’t agree with that because teenagers have always been invested in activism, now probably more than ever with all the information available to them. Teenagers care and are a lot smarter than we give them credit.

When did you know you wanted to be a writer? What it was like to get the courage up and make a real go at it?

I knew I wanted to be a writer when I was a very young child. I watched my father playing Dungeons and Dragons, and though I was far too young to participate in his campaign, I loved this whole idea that you can just sit down with a pen and piece of paper and build entire worlds. That was the coolest magic to me. I remember being seven or eight years old, sitting down with my notebooks. I would write twenty pages of handwritten notes about these fantasy worlds I would create. I existed entirely in my own head, and it was so fun.

I didn’t know that writing could be a serious thing to do until I was in my early twenties. I’ve dealt with some pretty severe mental health issues and sort of spun from my teenage years into my early twenties. I was twenty-two or twenty-three when I started to feel in control of my life again. I had to think about what I wanted to do, and I decided I was going to write a book. So I did. It was not very good; it did not get published, and I did not get an agent. Then, I wrote another book, and it also did not get an agent and did not get published, but it was a little better. Then, I wrote The Witch King, and now here we are.

I recently lectured at a university where students asked me if no one likes my manuscript, should I just self-publish it? I told them they need to keep writing and improving before they decide that because every great author I’ve known has burnt a couple books along the way. It hurts, but you just do it.

It does hurt. There were other books I started. I realized, sometimes as deep as 50,000 words in, that it was unsalvageable, I was going in the wrong direction, and I needed to just shelve it and be done. I don’t know much about self-publishing, I’ve never tried any of that, but I do know from what I’ve been told that it is a lot more difficult than people anticipate.

With every word you write, you get better.It is difficult, especially when you don’t have time to write because you are not paid to write. It’s difficult to hear just keep doing it and maybe it will pay off. I, unfortunately, do not have a solution to that.

When you were writing this book, did you feel this one was different from the ones before or were you just as in love during the writing process as you were with the scrapped books?

At the point when I started writing The Witch King, I had queried two other books, and I had abandoned two or three other manuscripts along the way. I felt like I was running out of time. I was still in my twenties and not actually running out of time, but I felt like I couldn’t keep putting all this time and energy into it. I was going to have to start making money. When I sat down to write The Witch King, I told myself I was going to make this the most honest, raw, and real story that I could. If it still didn’t work out, I was going to need to figure out a different path. From a logistical, financial standpoint, I couldn’t pour so much time into something that wasn’t going anywhere. So, as I was writing, I knew a lot was riding on it. It felt very different from the first two because it was the first time I had sat down with the resolution this is going to be my last shot, I’m going to give it everything I have. It was painful in ways to write because it was so real to me.

It shows how much heart went into it; it’s a fantastic novel. So, tell me about the technical side of things. You have a manuscript, and now you’re ready to query it. What was that query process like?

I had a few people that I’d queried originally who requested full versions of the last manuscript and passed on it but told me to let them know if I wrote anything else. I sent it to those people first. I also participated in a Twitter pitch event. The Witch King had some very flashy comparisons when I did the pitch event. It was compared to The Cruel Prince by Holly Black and Fever King by Victoria Lee, which I think got people’s attention. I got a lot of full requests very quickly because of that. Most of them didn’t pan out, but I did end up getting a couple of representation offers from the Twitter pitch contest. Then, one of the agents who I had sent it to previously and who had read another of my manuscripts also made an offer. And that is who I ended up signing with.

Once it was picked up and you worked with your editor, what was the biggest change between the draft you submitted and what I’m now holding?

The biggest change was Wyatt’s motivations. The first draft was a lot more violent because he was considering getting out of this marriage through murder. It was a darker story. The feedback I got was love the book, however . . . Wyatt is kind of irredeemable. And I said, I hear you.

Changing that one plot point overhauled the entire book. I rewrote most of the book in revisions to make it less of a super dark murder story. It was an interesting time. I signed my book right before the pandemic, and I also had a baby right before the pandemic, and then I had to rewrite the entire book. That was a time.

What’s next for you?

Right now, I’m working on the sequel. The Witch King is the first in a duology, so the second book will come out the summer of 2022. I’ve been having some very exciting conversations with people in charge about plans for the sequel. I also have a few other things in the works unrelated to this series—that I can say absolutely nothing about yet, of course.

We also have a preorder campaign of The Witch King. There are some really awesome incentives. We have signed book plates that are beautifully illustrated. I also made a custom The Witch King tarot deck. People who order during the preorder campaign have a chance to win a deck, but only five people will be chosen as winners.