The Thing with Depression: How Benjamin J. Grimm Helped Me Face Myself and Family Regarding Mental Health

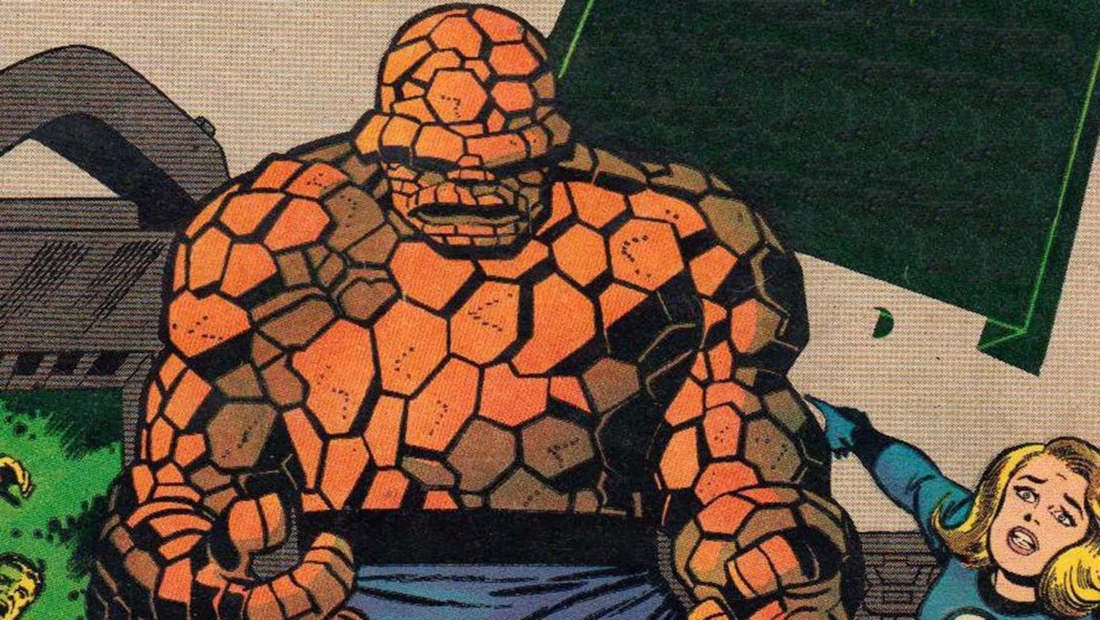

Words By Dominic Loise, Art By Jack Kirby

If you watch current Marvel movies, you haven’t seen The Thing mixing it up with the Avengers on the big screen. The Thing (Benjamin J. Grimm) mainly appears in comics and cartoons as a core member of The Fantastic Four. In 1961, writer, Stan Lee, and artist, Jack Kirby, launched four explorers into space in the first issue of The Fantastic Four. Once in outer space, Reed Richards, Sue Storm, Johnny Storm, and Ben Grimm are exposed to cosmic rays and gain superpowers. The twist: each of their subconsciouses affects their powers. Reed, always stretching himself too thin, became the elastic Mr. Fantastic. Sue, who felt unseen by people, became The Invisible Girl. Johnny, a hot head, became The Human Torch. And Ben, who felt like a working-class lug, became super-strong golem, The Thing. The combination of their relationships and amazing adventures laid the groundwork for the Marvel universe as we now know it. And what’s more, the series introduced a way for me to connect The Thing’s self-loathing to similar patterns in myself.

Depression isn’t just feeling sad. It’s normal to experience the whole emotional spectrum, but for myself, I found that sadness extended to a holding pattern of self-loathing. I’d find myself asking tough questions: Why am I sleeping all the time? Why am I pulling away from family and friends who only wish to check in? Though I recognized signs of depression, the stigma of asking for help kept me from turning to mental health professionals. It took not a rocket crash but a breakdown to learn I wasn’t a freak but someone with bipolar depression. Most importantly, I learned I was functional with the right medication and talk therapy. Ben’s own journey of self-discovery established his character as an icon for myself and my mental health.

Unlike Reed, Sue, and Johnny, who could switch their powers on and off, Ben was permanently turned into The Thing. Because of that permanence, Ben viewed his new powers and form as a curse rather than something that made him a superhero. He physically embodied depression. Whenever Ben left the Fantastic Four’s high-rise headquarters, he wore an oversized trench coat, shades, and pulled-down fedora. This wasn’t to avoid paparazzi but prevent him being seen as a spectacle. My own depression can often feel like stones piled on top of me, each stone representing a regret to be reviewed before I’m able to get out of bed and face the day. When my depression ramps up, I go around with my hoodie pulled low and headphones in to cut out the world. This is my way of disengaging and blocking stimuli, to stop negative thoughts avalanching in on me.

As the Fantastic Four’s story unfolded, it became clear that The Thing’s greatest power wasn’t his physical strength, but his perseverance. His catchphrase “It’s Clobberin’ Time!” signaled to villains he could take a licking and keep coming back for more. I found that perseverance inspirational but soon realized the flip side of it was a mental holding pattern—Ben couldn’t accept his current reality, which in turn, brought on his depression.

To try and explain why I didn’t feel connected to my present self, I searched for my own rocket crash or cosmic rays. My depression often felt as though one event could veer me off course—I was unaware that the period of joy in my life I chased was the manic cycle of bipolar depression. But, shortly after that period ended, I’d find myself sitting in the debris of the metaphoric crash site, waiting for a change to make things better without doing any of the work. Instead of rebuilding and relaunching, I reviewed my past trajectory for mistakes to relive, much like Ben wishing to be his former self. Ben and I both faced the stigma that men shouldn’t ask for help. With Ben’s depression, he saw only his monstrous form rather than the hero inside himself—with my depression, I was staying in my head, which kept me from being present in my current life.

When I first noticed my depression, I thought it best to live with my parents. But, whenever I ran into parents of childhood friends I felt shame for “living at home at my age.” Family told me those opinions didn’t matter, but my false perception led to career decisions that sped up moving out of their home. In turn, these choices took me away from a support system best for my mental health in the long run.

Ben made similar, rash decisions. There are storylines in which Ben felt better off leaving the Fantastic Four. But it was through the Fantastic Four’s growth as a family that Ben began to connect to his present self as The Thing. In the series, Sue and Reed marry and have two kids. These kids only know Uncle Ben in his Thing form. Seeing himself in this form as an uncle helped Ben embrace himself. When Ben first held his nephew, he said, “Now… All of a sudden… I feel like a part of a family… ’stead of a freak show!”

When you see Ben in the Marvel Universe relaunch of Fantastic Four, he’s not covering up his rocky orange self. Ben is in casual clothes tailored to his frame with his wife, Alicia, on his arm, helping people together. I like to think my version of a personal relaunch is talking honestly about mental health with all generations of my family, trusting their understanding, and being open about living with bipolar depression. I had my biggest breakthrough when I stopped looking for one specific event—or metaphorical rocket crash—to point to where things may have gone wrong. Instead, I started experiencing the present and utilizing tools from therapy to engage with the world rather than pull away. The Fantastic Four are known as explorers of the Marvel Universe—seeing similar patterns between my own mental health and in Ben’s expression of himself as The Thing, I began exploring my life again. Benjamin J. Grimm does not turn into The Thing at a whim, just as I don’t turn into someone with bipolar depression. Instead, it is who we are every day. It turns out that, after all, we aren’t the freaks we thought we were—instead, we are the heroes of our own stories.