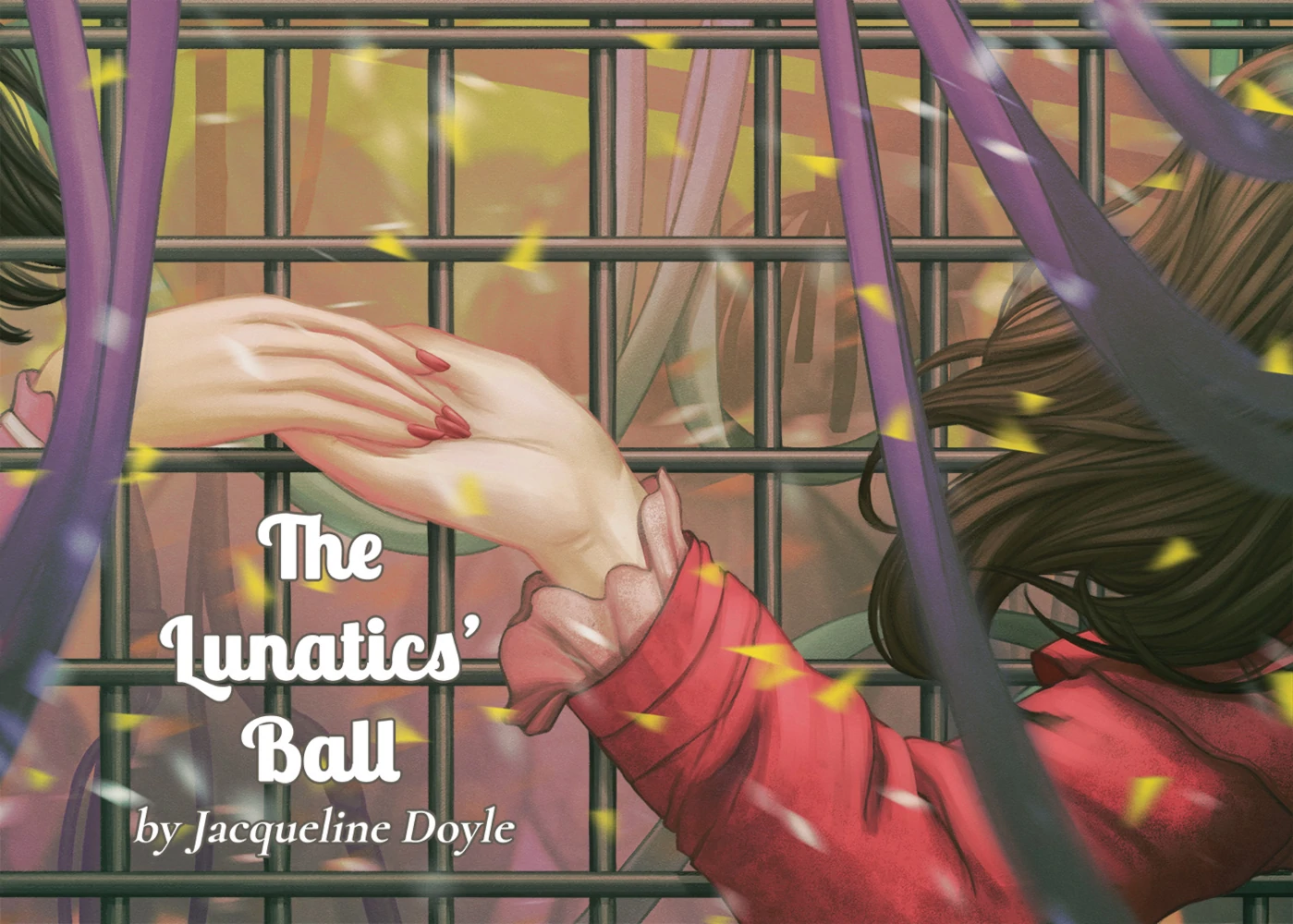

The Lunatics’ Ball

Words By Jacqueline Doyle, Art By Ejiwa Ebenebe

I remember the name “Greystone” from my childhood in the nineteen-fifties and sixties, spoken in a thrilling whisper. It was the local “loony bin” for “nutcases,” “fruitcakes,” “whackos,” “crackpots,” “maniacs.” At slumber parties, our variants of the “man with the hook” urban legend ended with an escaped lunatic from Greystone, his hook dangling from the car door. And in fact, Greystone did house sex offenders and violent criminals under treatment for mental illness, and there were escapes, though I don’t remember any reports of crimes like the ones you see on all the TV shows.

Greystone housed well over seven thousand patients when the singer Woody Guthrie was a patient there in the nineteen-fifties. By the nineteen-nineties, it was largely abandoned, after reports of rampant patient neglect, sexual abuse of patients by staff, patient escapes, and suicides. The buildings were later demolished. “Gravestone,” Woody called it. He died—in another psychiatric institution—of Huntington’s, a neurodegenerative disease initially misdiagnosed as paranoid schizophrenia.

If she’d survived, would my aunt Maddy have been treated at Greystone Psychiatric Hospital or someplace like it? She could have stayed on the lithium, instead of detoxing on the advice of a quack chiropractor. Or had second thoughts as the carbon monoxide fumes filled the garage. Or been discovered in time to save her life, instead of three days later. She was only forty-seven.

My mother told a story about a lunatics’ ball that her mother attended in northern New Jersey in the nineteen-forties—or maybe the thirties. Lunatics’ balls for inmates, staff, and visitors were common in late nineteenth-century insane asylums, less common later. It must have been at Greystone Psychiatric Hospital in Morris Plains, not far from Mountain Lakes, where my mother’s family lived. Did her mother have a relative there? If so, my mother either didn’t know or pretended not to. Maybe attendance was considered entertainment by small-town middle-class housewives. Or a kind of civic duty.

My grandmother danced with a charming, good-looking man who she assumed was a doctor. The punch line to the story was inevitable: he turned out to be a patient. A big laugh from my mother, as if no one in her own family could end up on a mental ward one day. When her younger sister Maddy was diagnosed as bipolar, my mother’s main concern was that no one in town learn of it. Maddy’s later hospitalization was a secret too. As was mine.

My aunt was only nine years older than me, and I followed her everywhere as a child, besotted. Maddy was the sister I didn’t have, the mother I wanted when I was a teenager, generous with her time and gifts. How to describe her? Gorgeous, charismatic, wealthy, fashionable, outgoing, extravagant. High strung. Sleek as a greyhound. My mother was jealous of all the time I spent with her, of her good looks and fancy house and wardrobe.

“She brought it on herself,” my mother said after Maddy’s suicide, lips pursed, uninterested in statistics about bipolars and suicide. My mother didn’t believe in mental illness or “witch doctor” psychiatrists. She believed in moral judgment, particularly of those she saw as unfairly favored by good fortune.

“We’re the two crazy ladies in the family,” Maddy said to me once. We were drinking red wine at an Italian restaurant, laughing about something. I was in my late twenties then, working on my Ph.D. It was before I got sober, before my own hospitalization and bipolar diagnosis. Only my closest friends, my parents, and my brother knew about my week in the mental ward—by then, Maddy was already gone.

When I look at the sketchy family tree my father started for my mother’s family, there are so many names I don’t recognize, so much potential for secret afflictions. Who was my mother’s Aunt Blossom? Her Aunt Florence? I never met my mother’s Uncle Tommy, an alcoholic who died in a hotel fire, probably a Bowery flophouse for drunks, but she mentioned him sometimes. The family said it was the First World War that made him drink. “It’s a good man’s failing,” the Irish say, always ready to find a reason or excuse. When I got sober, my father told me about the funeral of a relative, a great aunt I think, where her daughter took him aside and said, “She was an alcoholic, you know.” He didn’t know and was surprised to learn it. Shortly before Maddy died, she did a stint in rehab, probably for the painkillers she was taking for her back, though no one knew for sure.

Bipolar family trees invariably include more than two crazies—many relatives suffering from substance abuse disorders, others suffering from depression and anxiety disorders, and from schizophrenia. Scientists don’t know why. My mother never acknowledged that sleeping for ten years was a symptom of depression. “I had a lot of colds,” she insisted. For a while Maddy stopped speaking to her, after my mother claimed to be the “only normal one” in the family. “Does she think ten years in bed was normal?”

Much later, my mother didn’t believe that Lewy body dementia might be the source of her hallucinations. “Thank God we don’t have any of that in our family,” she said. When she was moved from assisted living to the dementia ward, she believed she was one of the nurses. “We had our hands full today,” she’d say when I called her on the phone. “Unbelievable.”

Are there other delusional relatives buried in our family past? Alcoholics and addicts who self-medicated for depression and other mental illnesses? Relatives excused as eccentric? Madwomen sequestered in attics? Who might my grandmother have known at the Greystone Lunatics’ Ball? There must have been more of us, hidden from sight, or slipping off the family tree like leaves in autumn, unnoticed.

In my dream, they’re playing Woody Guthrie’s “Cowboy Waltz,” two patients sawing away on fiddles, as I dance with Maddy at the Lunatics’ Ball. The tables have been cleared away, the Greystone hospital cafeteria festooned with red and green crepe paper. The Hawaiian punch mixed with ginger ale in the large glass punch bowls is strictly non-alcoholic.

“Did you know that Bob Dylan used to visit Woody Guthrie here at Greystone?” I ask Maddy. “Woody said folk songs should comfort disturbed people and disturb comfortable people.” Maddy laughs when someone shouts “hee haw!” and the sedate suburban matrons scatter, clutching their Visitor nametags.

Maddy’s still forty-seven in the dream, beautiful, but I’m sixty-seven now, showing my age. “You should get a facial, try Botox, honey,” Maddy says. “Maybe a brighter hair color. Why not go blonde?” She’s always full of outlandish advice. “I love that red dress on you,” she adds. “You look like a ripe tomato.”

She holds my hand aloft and we execute a perfect turn before whirling across the dance floor. One, two, three, four. One, two, three, four. The other dancers are a blur.

“This is fun,” I say. “I should take a dance class. Now that I’m retiring from teaching.”

Is that my mother joking with the nurses by the door? Maddy pretends not to see her, but I give her a friendly wave from across the room. I think I see my red-faced great uncles by the punch bowl, Uncle Tommy slipping a flask from the inside pocket of his jacket. And my grandmother! Her companions have their backs to me and I can’t see who they are. At home with the lunatics, I feel like I recognize everyone.

“I should have come sooner,” I tell Maddy.

How many years has it taken me to join Maddy at the Lunatics’ Ball? Fear of our dark kinship held me back. If Maddy and I were the two crazy ladies, and she took her own life, what would my fate be? Could I risk joining her in public? What would happen if my colleagues and students and acquaintances knew I was bipolar too?

“Get a letter from your GP instead,” the department secretary whispered to me at my first job. “You don’t want a note from a psychiatrist in your permanent file.” A department chair in my second job counseled me not to tell. “When people know you’re bipolar, that will be your label. They’ll think of you as just one thing.” I worried too much. Let them think what they want.

Now that I’m finally here, I’m so glad to see Maddy again! The lights blaze, the Christmas decorations glitter, the musicians strike up a new tune on their fiddles. We twirl and spin, dancing, laughing. I’m not sure I ever mastered the box step, but it’s all coming back to me. I let Maddy lead.