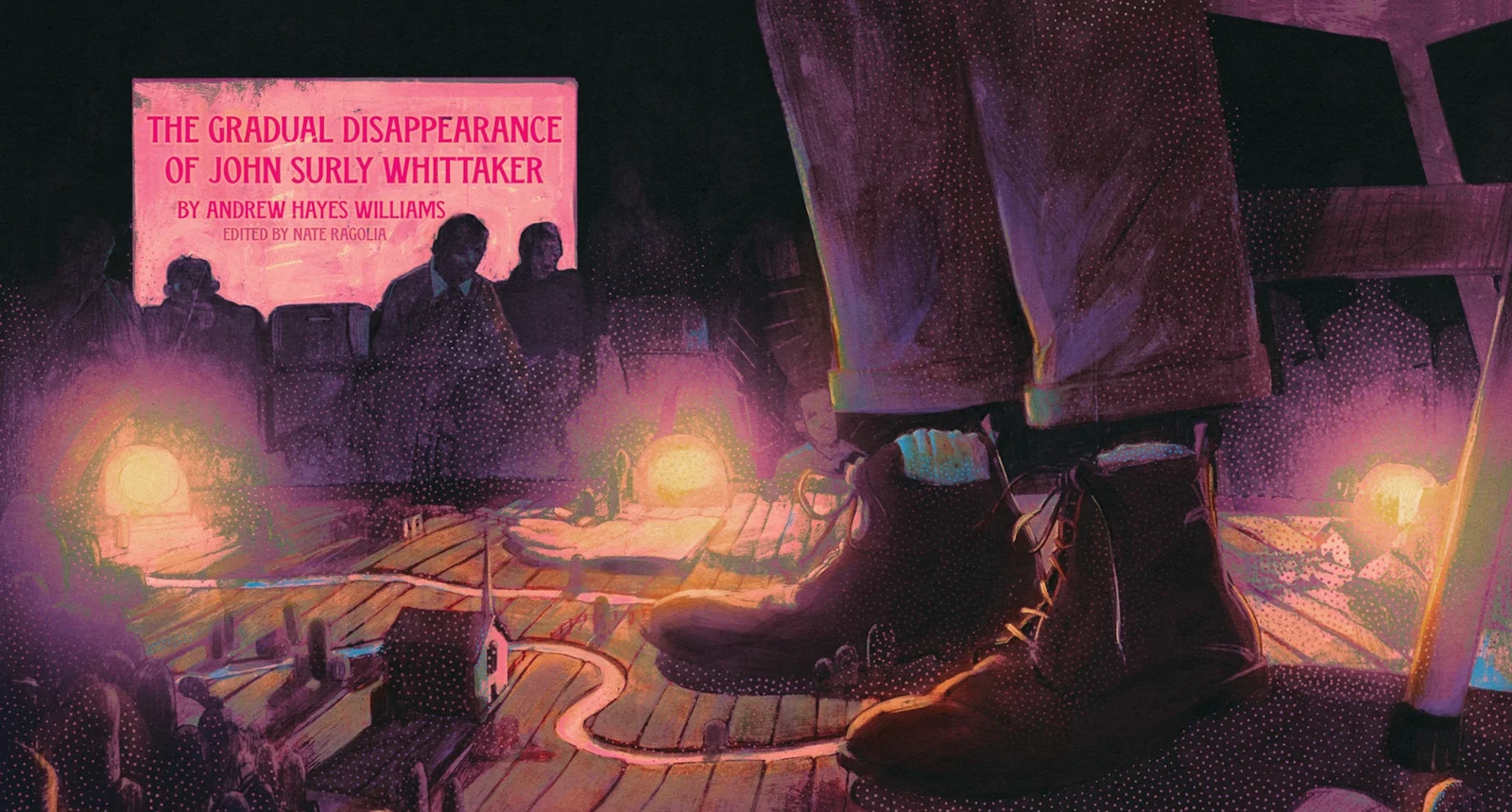

The Gradual Disappearance of John Surly Whittaker

Words By Andrew Hayes Williams, Art By Braden Maxwell

By the time John Surly Whittaker lumbered onto the stage, he was already missing his fingers and toes. The audience didn’t realize he had been vanishing since 1885. Nor did they realize that parts of him were missing under his gloves, shoes, and custom-made suit. Still, they all turned wide-eyed when they saw him, for pictures and videos didn’t prepare them for his presence; the sense of being in front of a human tree could only be felt in person.

The fifteen-foot man was covered in bark. Moss gave him brows and a Lincoln beard. Rather than locks of hair, he had vines of leaves dangling down to his upper back. Lavender irises floated in the dull honey-yellows of his eyes, rendering the blackness of his pupils oddly extraordinary.

“Mr. Whittaker,” began the host of the university’s 2024 Literary Arts Festival.

“Surly, please.”

His croaky baritone had been captured in countless recordings (including his interview with the Federal Writers’ Project of the WPA), but only in his company did his voice rumble your bones.

“Surly.” The host nodded. “Would you please be so gracious as to sit through a brief interview with me?”

“It’s why I’m here, after all.” His joking smile didn’t condescend, just as his brown teeth didn’t appear rotten.

On the projector screen behind them, the slideshow flipped from the festival’s logo to a brief biography of Surly’s life. Ten bullet points tried to convey who he was, whatever he was.

Even now, Surly didn’t have an answer himself.

Despite his stature, he felt small. Despite the crowd, he felt alone. Everyone felt alone if they were honest about it. In the face of every stranger, he saw the pain of someone yearning to be loved. That’s all life was, in the end: a thousand unfulfilled love stories. To feel unworthy was a deathly burden, a sacrifice of everything to the god of nothing, and he sensed the room was filled with hidden crucifixions. Soon, his own cross wouldn’t be so hidden. What a wretched thing he was. What a wretched, little thing.

He blinked a few times, then said to the host, “Ask me what you like.”

By then, his loafers were empty—everything up to his ankles had vanished.

It was fitting for his existence to end in a theater, because the long, remarkable life of John Surly Whittaker plays out like a tragedy in three acts:

Act I:

The Girl in Mourning

Act II:

The Haunting and the Dream

Act III:

The Gradual Disappearance

It tells the story of a tree man who went off to war, fell asleep for twenty-two years, and started to vanish when he woke up. That said, if you asked Surly himself, he would say it’s the story of a single thing, the thing by which he’s eternally defined. Not his fame. Not his form. It’s the sin he committed when he joined the Union cause—and the guilt that ate away his body as a result.

The curtain rises with his manifestation. One night in the summer of 1855, he appeared inside an old church in Boston. His bark felt warm and hard against his body, creaking with every fidget, every blink, every step. Though he wasn’t a child in body or mind, he tried to let out a cry. Nothing emerged from the knothole of his mouth.

While no one knows how or why he came to be, the prevailing theory is that writers had spoken him into existence. After all, he popped up the day Leaves of Grass was first published, and he appeared inside the Second Church, where Ralph Waldo Emerson had been ordained as a Unitarian minister. The greats of that era had been trying to invent “America’s voice,” so perhaps he was a strange apotheosis. Or, perhaps, he was an accident of nature.

At any rate, for the first six years of his life, he sheltered in the woods. If anybody wandered in his direction, he would straighten his spine to camouflage with the trees. This only worked for so long. After the first sightings of him, he became a local legend, like Bigfoot or the Headless Horseman. Soon came the righteous monster- hunters, deeming him a product of witchcraft or paganism. He was struck with knives and axes more than once, his body growing back every time. After a few attacks, he realized he couldn’t die. He took no comfort in the fact.

Pain didn’t affect him much, either. Every blow came with mild discomfort, like clipping your fingernails a little too low. What hurt was how people spoke of him, the way they decried his monstrosity. They were right, of course—what was he?

Animals would hunt and forage for food, but he never hungered; they copulated, but he possessed neither the capacity nor the drive. As for trees, he envied them: they’re nothing more than what they are. He wished his soul would vanish from this cage of bark. One day, he closed his eyes and prayed for an end until…

“You’re the one they talk about.”

He turned around and saw a fifteen-year-old girl. At that point in his life, he wasn’t yet able to speak, but he nodded at her, for he could understand with perfect clarity.

“What’s your name?” she asked, taking a step toward him. She was dressed in black and holding a sketchbook.

He shook his head.

“Haven’t you got one?”

Again, he shook it.

“Mine’s Ellie.” She put a hand on his leg, examining its bark. “Aren’t you lonesome out here?”

Having company had never seemed conceivable to him, so the feeling of isolation was difficult to recognize. All at once, someone was there with him, addressing the emptiness inside. It was like seeing himself in a mirror for the first time.

“I didn’t mean to make you cry,” she said. “But I understand it—I’ve been lonesome, too. Real lonesome, ever since…”

She held up one of her sketches. It showed a young man with a round face and a head of messy hair.

“My brother. He died a month ago at Bull Run.”

He stared at her as if she were speaking in tongues.

“You don’t know Bull Run? Do you know about the War at all?”

He shook his head.

“It’s about saving our soul as a nation. At least, that’s what my parents say.”

He gestured with his hands, trying to find a way to communicate.

“Can you write?” she asked, holding up her sketchbook and pencil.

He assumed the answer was no, but when he tried, he was capable.

What do you miss most about him?

“At his funeral, everyone talked about how gentle he was, how polite and softspoken. That’s not how he was with me. He had so much energy. He had this way of saying my name. ‘Ellie,’ he’d say. Every time we bickered, or every time he wanted me to believe something, ‘Ellie, Ellie.’ I think I miss that the most. When I realized I’d never hear it again… that’s when it hit me.”

She sniffled and wiped her nose.

“I still talk to him sometimes. I close my eyes and imagine what he’d say if he was with me. I hear him talk about the War, about his plans for his twentieth birthday. I hear him talk about girls. He really liked girls. I hear him talk about his dreams. ‘I’ll be a famous riverboat captain—you better believe it, Ellie—after I’m a hero in battle.’” She took a deep breath. “And when I hear him in my mind, I say his name. I don’t know why. It’s almost like it brings him back, only for a second, like if I have a reason to say it, he isn’t really gone.” She looked up at him. “I know it doesn’t make sense. You must think I’m pretty stupid.”

He shook his head so quickly that leaves fell from his vines.

You build monuments with words. His handwriting was rigid, like letters made with sticks. The way you speak of him, it makes me feel I know him.

“I can’t stop thinking about his funeral. His body, he seemed so… small. He never used to look small to me. I hate to think about him being small.” She hugged her knees, hiding her face behind them. “What do you think it’ll feel like when we go?”

I cannot die the same way humans do.

“What will happen to you, then?”

I’ll find out if the time comes.

“Whatever it is, for you and for me…” She closed her eyes, imagining it. “I hope it doesn’t make us small.”

The host of the event cleared his throat.

“To start, I’d love to explore your literary influences. Which authors had the greatest impact on you?”

“The ones Ellie showed me.”

“Ellie Berkower,” the host clarified for the audience. “A respected poet in her own right. She was part of the Realist movement, though she’s often categorized as late-American Renaissance. There was a resurgence of interest in her work a couple decades ago, when researchers from Harvard—”

“Words for common people,” Surly cut him off. “That’s what I like.” He didn’t want Ellie spoken of in academic terms. It wiped her personality from his memory. “That’s where truth is, she always said. Stuff like Emerson and Thoreau.”

“Their philosophies informed your book?”

(His book, his only book, The Ghost of Henry Clemens, published by Charles L. Webster and Company in 1886.)

“Partly. I wrote that book because of my dream. I wanted to make sense of it.”

“Your dream, yes. The driving force of the narrative.”

“I have a heart, but it doesn’t beat. I have lungs, but they don’t breathe. What makes me closest to human is my dreams.”

The host turned to the audience. “I assume we’re all familiar with his famous dream, the subject of his book?”

Tepid mumblings came from the crowd.

“Henry Clemens; he died working on a steamship,” Surly said. “The boilers exploded.”

“The Pennsylvania. A famous tragedy.”

“That’s what I saw in my dream. I saw it sink. I saw Henry emerge from the water. My book is about the conversation we had.”

The host put a hand on his chin. “I have to say, the epistemological aspect of your work, the self-referential quality of it, it’s an astonishing prediction—early encapsulation— of postmodernism.”

“I don’t understand anything you just said.”

The crowd laughed. The host quietly scoffed at them.

“I mean, it was unusual to write a memoir that focused so little on the events of your life, and so heavily on exploring your dream.”

“‘Nonsensical’ was what the critics called it. Everyone said the ghost should have been Ellie’s brother, that it would’ve made more sense.” He kept his legs still, careful not to reveal what was happening to them. “I just wrote the truth of it.”

His pant legs dangled. He was gone below the knees.

The dream in question occurred when he was serving in the 22nd Massachusetts Infantry. He fell asleep on the battlefield at Gettysburg. Thinking he was dead, the army had his body shipped back to Boston, where a memorial was constructed and his body was placed on display. The mausoleum was meant to be temporary, but when his body didn’t rot, they decided to leave it. For twenty-two years, he slept there.

Then he woke up, and he could speak.

The discovery happened by accident, and his first words weren’t a grandiose affair. He was dragging his feet through an industrialized town, gaping at the sight of smoke-stacked factories, unaware of how much time had passed since he’d fallen. Workers on the crowded streets gawked at him, and a reporter for the local paper happened to pass him by.

“John Surly Whittaker? John Surly goddamn Whittaker?” Nearly falling over, the reporter held up a notepad. “I’ve struck gold, my friend. You’re giving me an interview right now.”

Surly couldn’t find his diary, so the thought came out of his mouth:

“All right, then.”

As soon as it happened, he wanted to visit Ellie. He indulged the reporter in a few questions, then returned to her house. He had been there once before, to meet her parents on the eve of his enlisting. All these years later, he could still recall every detail of that night:

“Mother, Father,” Ellie said. “This is the friend I told you about, the one I’ve been visiting the past six months.”

Stoic, dressed in black, they each shook his hand.

I’m sorry for your loss, he wrote. Ellie has spoken of your son with adoration.

Their gaze drifted over to a framed photo on the fireplace mantle—a nineteen-year-old boy in uniform, bushy hair beneath a Union cap, thin brows, a rounded nose. His expression seemed like he was trying not to smile. And his eyes, they looked alive: two portals to eternity on a shiny daguerreotype.

His courage inspired my decision to enlist, he wrote, holding up the notepad for her parents to see. They gave approving nods, and the four of them sat down for supper. At grace, they blessed the boy, blessed the Union, and blessed the pork and potatoes. Ellie maintained her composure through the meal, but once it was time to say goodnight, she broke down crying.

At the foot of the porch steps, she hugged him.

“I don’t want to lose you, too.”

It won’t be like that. You know I can’t die.

“I’m going to feel so alone without you.”

I’ll see you again. I promise.

That supper took place in the spring of 1862. Twenty-two years later, after falling, dreaming, waking up, and walking back, Surly returned to the house at last. “I’m here, Ellie,” he practiced saying the words aloud. He knocked on the front door, readying his arms to wrap around her, when a stranger answered.

“Good Lord,” said the middle-aged man, eyes bulging.

“Is this no longer Ellie’s residence?”

The sensation of talking was so new to him that he could feel each word rumble his Adam’s apple.

“She said you couldn’t speak.” The man covered his mouth. “Otherwise, you’re just as she described.”

“You know her, then?”

“Knew her. Intimately.”

Surly’s heart had never beat in his entire life, but he could have sworn it thumped just then.

“Randall Berkower.” The man extended his hand.

“How did it happen?”

“Tuberculosis. It’s been seven years since she passed. Her parents are both gone, too.”

The novelty of speaking seemed pointless now.

“Forgive me if I wasn’t clear, but Ellie was my wife.” Hands on his sides, Mr. Berkower shook his head. “We thought you were dead. It was written in the papers. The Union’s ‘Tree Man’ Perishes at Gettysburg.”

“I didn’t perish. I fell.”

“Not dead?”

“Dreaming. How long has it been?”

“It’s 1885.”

“And the War?”

“Over. Won.”

“Very good.”

He tried to peek inside the house. It was too dark to see anything.

“The United States are healing?”

“The United States is healing,” Mr. Berkower corrected. “It’s singular now. And to answer your question—badly.”

“It seems I’ve missed a lot.”

Mr. Berkower held up a finger. “Wait right here. There’s something she would want you to have.”

After disappearing into the shadowy house, he returned a minute later with a thin book, bound in cerulean cloth with a floral design. Its title protruded in black, capital letters: ELLIE BERKOWER’S POETICAL WORKS. He flipped through the pages. One poem caught his eye. It was simply titled “Requiem.”

For when I dream of what I’ve lost

Unto this age of sordid vanity

My heart must wonder if it’s true:

In saving our soul, we might lose our humanity.

Thanking the man, he stepped off the porch. At the sound of the door shutting, he ran. Into the night, into the forest, he stumbled forward until he collapsed to his knees and howled.

“Ellie,” he cried. Just as she used to say her brother’s name, Surly repeated it over and over to feel like she was here with him—“Ellie, Ellie, Ellie, Ellie.” How could she be dead when the word still felt alive? It vibrated his vocal cords on the way up his throat. It raised his tongue to form the second syllable. It echoed off the surrounding trees, as if they were consecrating it, awakened by its power. And there, on the book in his hands, he could see it. He could touch it. Her life remained in her name, just as her soul remained in her poems—it felt true, axiomatic.

Yet she was gone.

In an instant, he felt cold. His bark itched like never before. There was a mild pang in his left hand, and he held it up to examine his palm. There had always been rings on it, one for every year of his life, and he assumed the discomfort was coming from the markings of his past. What he didn’t feel was the tip of his index finger fading away, a jagged point of bark and nail sinking by the millimeters.

When he noticed it, he pinpointed the feeling—a slight, fuzzy tingling, like a limb that’s fallen asleep. It didn’t hurt and it didn’t feel good. It was an indolent, passionless kiss of death.

“So this is how I go,” he proclaimed to the trees. And as his newfound voice signified his fate, a local paper was preparing its next headline for print:

MIRACLE! THE TREE MAN LIVES!

“While we’re on the topic, I have to ask,” said the host. “Were you at all affected by the reception to your book?”

“I can’t say I was fond of the derision. Even a few years after it was released, when Charles L. Webster and Company shut down, it was referred to as the publishing house’s first great failure. I felt guilty—like I cursed him.”

“By ‘him,’ I assume you’re referring to Mark Twain, who founded the short-lived publisher?”

Surly nodded.

“There’s something I’ve always wanted to know,” said the host, “about your relationship with Twain—or Samuel Clemens, if we’re being proper. Your entire novel is a conversation between yourself and the ghost of his brother. What on Earth did he think of it?”

“He found it moving. He had dreams, too.”

“Yes, recurring dreams about his brother’s death leading up to the accident. He’d gotten his brother the job on the steamship and blamed himself for his death. It weighed on his conscience tremendously. But what makes your book so eerie is that you were asleep when Twain published Life on the Mississippi, in which he first discussed the accident. And yet, you dreamt it. You dreamt of the accident; you dreamt of the boy, whom you had no way of knowing. How could that be?”

“Life and death aren’t linear, not quite.”

“I beg your pardon?”

“You’re alive when you’re spoken of. You’re dead when no one knows you.”

“Death as cultural invisibility?”

“In the War, all the boys were terrified of ending up as nameless bodies.”

“It was the fate of many Northern soldiers.” The host turned to the crowd. “The percentage, I believe, ended up around 40 percent. The government didn’t issue dog tags until after the Civil War.”

“Without a name, you’re nothing.”

“You’re nothing without a name,” the host repeated backwards, like a recalcitrant echo. “It’s interesting that we keep circling back to the War.”

“The War is where I went astray.”

When his hands were almost gone, Surly hid his arms behind his back. Just before his gloves fell to the floor, he shifted a bit, pretending he was taking them off.

The host raised a brow. “I assume you’re referring to…”

Here it is, the sin for which he could never forgive himself.

The air was warm and thick with cigarette smoke when he walked into the Union’s local recruiting office. It was a tiny cube of a converted law firm with limestone bricks and a pyramidal roof. With everyone staring at him, he stepped up to the table and wrote, I’m here to enlist.

He thought he’d have to defend his color and his speechlessness—but he wasn’t of any race, so they had no grounds to turn him down, and his ability to hear proved satisfactory. The reason was this: the Confederates had a giant of their own, Martin Van Buren Bates, whom the Union army wanted to rival.

“What’s your name?” asked the wide-eyed recruiting officer.

My friend calls me the Tree Man.

“I’m afraid that’s not a name. I’ll let you fight— don’t worry about that—but you’ve got to give me something real.”

This felt like a sacred test, like the recruiter was Saint Peter guarding the gates of heaven.

The Tree Man put his pen to paper, trying to make something up. What came out was the name of Ellie’s dead brother:

John Surly Whittaker.

And thus, in his view, should end the play of his life:

(The recruiter signs his registration form.)

(Exit the Thief.)

CURTAIN

What followed was an epilogue, overwrought and laborious, spoken by a rambling god with no thought of redemption.

Perhaps he would feel better if people despised him for what he had done. Years later, when his book came out and he revealed his crime, the critics deemed him melodramatic. What harm, they asked, had been done by the act? Surly had killed soldiers in the War—really killed them. If he needed to write a treatise on his sin, why not focus on the fallen?

This sentiment bewildered him. No one questioned the fear of unmarked graves, but somehow, his remorse of stealing a name defied comprehension. Had he not, in his own way, rendered Ellie’s brother as invisible as the nameless?

Had he not scraped the letters from that boy’s tombstone and worn them around his own neck?

In the decade that followed his book’s publication, he visited every anonymous grave he could locate, trying to understand. His left index finger would shrink every time he stared at those blank slabs of stone: Here lie the poor, the convicted, the enslaved. Here lie the forgotten, deader than the rest.

No amount of searching changed his perception of himself. All he gained was deeper admiration for Ellie. She had always said that truth was in the voice of the common person, and he knew there was truth, essential and irretrievable, buried in these American graves. This plot of lost stories was overrun with weeds. This poem of a country, blotted by missing words and imperfect rhymes—oh, how pretty it could have been.

After ten years of failing to find peace, Surly vowed to find purpose instead. In 1896, he was a vocal advocate for the William Jennings Bryan presidential campaign. Ellie would have loved the candidate’s anti-elitism, and there was one clear sign he was doing the right thing—his spindly left index finger, which had shrunk to the middle of its nail the past decade… during the campaign, it didn’t vanish further.

Indeed, whenever he felt the most confident about himself, the process of disappearing slowed to a halt. Nothing shrank away, for instance, in his decades as a movie star—evading Harold Lloyd’s weakly lumberjack in Timber! or kidnapping a beautiful ingenue in a rip-off of King Kong. Then he got subpoenaed before the House Un-American Activities Committee, largely due to his populist past, and he disavowed his values to save his career. So there, his right index finger—there it started to go, joining his left one in fading at the tip.

“Should I fight it?” he asked himself, his eyes locked on the deepening divot.

He wasn’t afraid for his life to end. He never had been. Despite his bark, despite his leaves, it was the least human thing about him. He was, in fact, ready to leave the world behind, and if self-loathing would hasten the process, he decided to fully sell out.

That was why, for a handsome royalty, he agreed to be the brand mascot for Monsanto. Sketches of his smiling, tree-shaped form filled the labels of DDT insecticide bottles in stores across the nation. He attended fancy parties. He stayed in luxury hotels. All ten of his fingers shrank by degrees.

He hated himself, yes, but he didn’t regret it—not until Vietnam, when Monsanto started producing Agent Orange. At that point, he wondered how significantly his image had contributed to their profits, if his face bore any responsibility for the thousands dead and wounded overseas. The guilt was so overwhelming that he tried to remove himself from the brand, but his contract was locked in.

For the next few decades, he hid in his home. He unplugged his phone so he wouldn’t hear it ring. He threw away his mail, unopened. Even after 9/11, when he experienced a brief resurgence in the pop culture imagination, he never did interviews. He barely read the news. He wanted to become nothing since nothing was becoming him.

At first, he thought disappearing was his punishment. By the aughts, it seemed like a mercy. Death’s lethargy, that was the real retribution—Christ, how he diminished slowly. Only in his final year did the process hasten, as was the case with any terminal disease. That’s when the dread of dying alone started getting to him. That’s when he agreed to speak at a local university.

“No one understands it.” His croaky baritone didn’t rumble. It whimpered. “No one understands the significance of the crime.”

“I think you’re being too hard on yourself,” said the host. “Of all the sins that come to mind, yours is quite innocuous.”

“I stole”—legs shrinking.

“Intangibly.”

Gone to the knees.

“The theft of a name,” the host added, “is purely theoretical.”

“For all your talk of theory, how is this the theory you dismiss?”

Still hidden behind his back, his arms were nothing past the elbow.

“Apologies,” said the host, “but if I might ask, what is it you’re looking to hear?”

“Nothing you can offer. I needed it from Ellie. I needed her to forgive me.”

In the following silence, Surly waited for something trite, something pretentious, or something merely wrong.

“You’ve never read the poem?” The host’s mouth hung open. “Dear God, tell me you’ve read the poem.”

Surly shook his head.

“Can we get it on the screen?” the host called to someone in the back of the theater. “I can’t believe you didn’t know about this, Surly. A few of Berkower’s unpublished poems were found during an estate sale. It was a big story in the academic community, even got some mainstream press. This was twenty years ago!”

“I was incommunicative.”

“Incredible.” The host rubbed his face. “One of the poems was clearly about you.”

A poem filled the projector screen behind them. His body wasn’t able to turn.

He knew he had no choice—he couldn’t hide the process any longer.

“Please,” he said, holding up the stumps of his arms.

Confused mumbles spread throughout the audience.

The host covered his mouth. “Jesus Christ, are you…?”

“Yes, help me—”

His lips kept moving, but the words stopped. That’s when the audience’s mumbles became a clamor:

“Oh my God! Oh my God!”

Entering his final minutes of life, Surly felt like he was taken out of time. He’d experienced something similar in his dream all those years ago—like there were no beginnings or endings, no distinctions between life and death, no phases in some vast continuum. There was only this moment, which was every moment: speechlessly waiting for the slouching god of mercy.

Show me her words before I’m gone, he prayed.

At the behest of grace, it happened.

The first time he was shot was at the Battle of Gaines’ Mill. He didn’t fall. He barely stumbled. The Confederates won, ending the North’s advance on Richmond—but a legend began that day, a media campaign to salvage morale: John Surly Whittaker, the mysterious Tree Man, embodied the Union’s soul.

So claimed the poems about him in Harper’s and The Atlantic, rhyming allusions to biblical heroes in endless stanzas of metered hagiography. So argued the bounty of editorials, struck by the symbolism of his indestructability—John Surly Whittaker Cannot Die! Neither Shall Our Union! The more of a symbol he became, the larger his persona grew. The larger his persona grew, the smaller he felt in his mind. The guilt of stealing his name was growing unbearable.

He needed to explain himself to Ellie, but he couldn’t figure out what to write. One night, as he sat by the fire, he made an attempt:

My dearest friend,

I can only imagine your sense of betrayal. I want you to know that I never intended to erase your brother. It was meant to be a tribute.

He nearly snapped his pencil.

And yet, that feels dishonest. The truth is this: when I was asked to provide a Christian name, his was the first that came to mind. I claimed it without meaning. I stole his life like an impetuous king, a despot who executes his subjects on a whim. I took his name, and all that comes with it, and I barely gave it any thought. That’s what weighs on my conscience more than anything.

I’m not asking you to forgive me, Ellie. My only request is this. When you speak his name, I hope he still feels alive to you. I hope you hear him talk about girls, about his birthday, about his future. I hope it signifies the dreamer, the boy as you once knew him. I hope it doesn’t signify me.

He sent the letter off and hoped for a reply. Three days later, the Battle of Gettysburg started. The 22nd Massachusetts Infantry arrived at noon on the second day. They rested while the generals strategized, but Surly couldn’t sleep. He wanted to hear from Ellie. He wanted to undo his enlistment, undo his existence if that would make it right. All he could do was stare at his comrades. On paper, copper, or little bits of wood, their names were attached haphazardly to their clothing, lest they be doubly killed. Indeed, many of them would fall once the generals made up their minds where to send them, but the boys slept. It was eighty degrees and their uniforms were made of wool, but the boys slept. Gunshots and cannons rumbled the air, taunting attrition, but the boys slept. And Surly couldn’t.

He resented his immortality. He wanted to gift it to these young men, one hundred and thirty-seven versions of Ellie’s brother—each filled with dreams, each unique and purposeful, and each more worthy of life than him. There he sat, awake, envisioning the children they would never get to have, the generations that would never get to be. In all those stolen lives, what stories would never be told, what art never created, what songs never sung? Every person was a kingdom. Every murder was a genocide.

But the boys slept. And Surly couldn’t.

Not yet, at least . . .

At 4:30 p.m., they were called to arms. They set up near a peach orchard at Stony Hill, piles of cartridges at their feet, ready to reload.

A Confederate brigade from South Carolina charged them. Like a pack of coyotes closing on its prey, they howled. Shots rang out in all directions. The air was thick with smoke. Surly widened his stance, preparing for the bullets to tear into his body as—

“Mr. Whittaker.”

The voice came from behind him. The world turned slow and silent as Surly looked over his shoulder, twisting the bulk of his torso, and saw a ghost.

The ghost of a nineteen-year-old boy.

And there, the bushy hair—and there, the rounded nose—and there, those dark brown eyes, those portals to eternity burned on that daguerreotype…

It had to be Ellie’s brother.

Surly didn’t feel himself fall. Nor did he feel his eyelids close. But all at once, the battle felt distant, as if it had happened a thousand years earlier.

When he opened his eyes again, he was on the bank of the Mississippi River. 300 yards away, a steamship was floating by. He was too preoccupied to be confused.

John!—he mouthed the word. For the first time in his life, he forgot he couldn’t speak. John, come back to me! Please, let me apologize!

With a resounding bang, the front of the steamship exploded.

Unable to swim, Surly helplessly watched as the ship started sinking and passengers jumped over the side. As the minutes passed, he wondered if he was in hell.

Then the ghost from Gettysburg emerged from the water.

You’re here! Surly thought. Thank God, it’s really you!

“Y-you know me?” the boy stammered, able to hear his thoughts. “I know you. I’ve seen the posters and heard the tales, but… you know me?”

Are you not John Surly Whittaker?

“I thought that’s who you were, sir.”

It is and it isn’t. I have his name. He shook his head. You’re not Ellie’s brother? You didn’t die at Bull Run?

“Sir, that isn’t me. My name is Henry Clemens.”

You don’t understand. If you were him, you could forgive me! If you were him… and you’re so close…

Surly fell to his knees. The universe had sent him a facsimile of grace. Redemption, it seemed, was the domain of frivolous gods.

Why am I with the ghost of a stranger?

“I’m only a ghost of sorts, sir. I’m not dead yet, not quite. My soul is here with you, but my body is lying on the floor of a great hall in Memphis. It’s where they took some of the wounded.” He held up his shirt to show his burned body, which was covered in cotton and linseed oil. “I’m asleep there, dreaming, fighting off the reaper.”

So this is a dream, or something like it. Surly didn’t know how to feel about the realization. It’s 1863 for you?

“1858. This is the way of things, sir: I’m able to see stuff here in my dream, stuff that hasn’t happened yet. I’ve been searching for you in my dream a long time, ever since I learned you couldn’t die.”

If I could offer immortality to others, I’d have done it a hundred times by now. He should have felt as fragile as glass. He felt more like a bulk that shattered the universe. We’re looking for salvation from each other, and neither is able to grant it.

Defeated, Henry stared out at the water, at the remnants of the flaming steamship.

“I don’t know what to do. I’m so scared. As I lie in the great hall… I hear screams of pain.” He closed his eyes. “I see people going to the death room.”

The death room?

“That’s what they call it, the room they take the lost causes. They think if we see someone die, that will make us lose morale, so they hide ‘em in that room. I don’t want to go to the death room, sir.” Tears filled his eyes. “I guess I’ll be there soon enough.”

Surly couldn’t help but pity the boy.

What is it that worries you about it?

“Dying? What comes next… if it’s anything. I fear what it could be almost as much as I fear it being nothing at all.”

Nothing at all—a century and a half later, that’s what he was becoming on the stage. The tragedy of John Surly Whittaker was ready for its curtain.

And thus, in history’s view, would end the play of his life:

(The host runs over to Surly’s chair. He turns it around to show him the poem.)

(Surly reads the title.)

“Every Time I Speak Your Name”

“What’s it like,” Henry asked him by the water, “knowing you’ll never die?”

I suspect my life will end somehow. I just won’t die the same way men do.

“So you do have cause to fear it?”

Surly shook his head. What troubles me is something else. I purloined my name.

(The audience rises in the theater. They hold up their phones to record the spectacle.)

“I’m not sure I understand,” Henry sighed. “All I can say is you’re lucky, lucky not to be afraid of passing on.”

You have nothing to fear, either.

“How do you figure?”

Death is the absence of life, not a negation of it. It’s the negation that worries me.

“You fear what someone could do to you once you’re gone?”

No, it’s him I worry about. What I did to him. What I took from him.

(Surly falls off his chair.)

(The audience screams.)

“I guess what you’re talking about is…” Henry’s eyes widened, as if in realization. “I’m in the death room. They’ve taken me to the death room! Please, sir, is there nothing you can do to save me?”

(Bits of dry, old bark fall off his head. The empty sleeves and pantlegs flop. He’s nothing but a head and torso.)

I can remember you. I can help make your name known to the world. I believe it could save you in a sense.

It didn’t feel like a false prophecy—just a bad translation of divine truth.

And anyway, it’s all he had.

(Vanishing, he reads the poem.)

There were some who deemed you holy,

A sacred soul with timber frame,

But you live mortal in my mind

Every time I speak your name.

He read it, over and over, until his eyes became nothing. Nothing—there, beneath the empty sockets, his nose shrank away, his lips became nothing.

To me, you were no Union god

Though requiems all make the claim.

I see you hiding in the woods

Every time I speak your name.

His face, as it diminished, became a stump for locks of leaves, flattening into a plank of featureless nothing. The hollow neck, nothing. The hair of vines, nothing. Each speck of bark, each fallen leaf, nothing, nothing, nothing, nothing.

No matter how you lost your time,

No matter what you each became,

I signify the two of you

Every time I speak your name.

In his last, lingering consciousness, whatever it was, in the ephemeral remains of his moribund mind… there, in that blackness, he saw Ellie and her brother.

If only I could let you know

You have no cause for guilt or shame

Because you’re with me—you and him

“It’s happened, sir,” Henry said. “My life is over.”

How do you feel?

Henry had to think for a moment. He raised his chin.

“Enormous.”

In the void, John and Ellie smiled at him. “Oh, thank God,” the Tree Man cried, taking a step towards them. “Oh, thank God. Oh, thank God.”

Per his will, he had his belongings donated to the Smithsonian…

“Oh, thank God. We’re infinite then!”

…and there his suit lies empty.