The Dark Evidence of Light: An Interview with Claire Bidwell Smith

Words By Claire Bidwell Smith, Interviewed by Dani Hedlund

Please note that this interview was originally published on our old website in 2015, before our parent nonprofit—then called Tethered by Letters (TBL)—had rebranded as Brink Literacy Project. In the interests of accuracy we have retained the original wording of the interview.

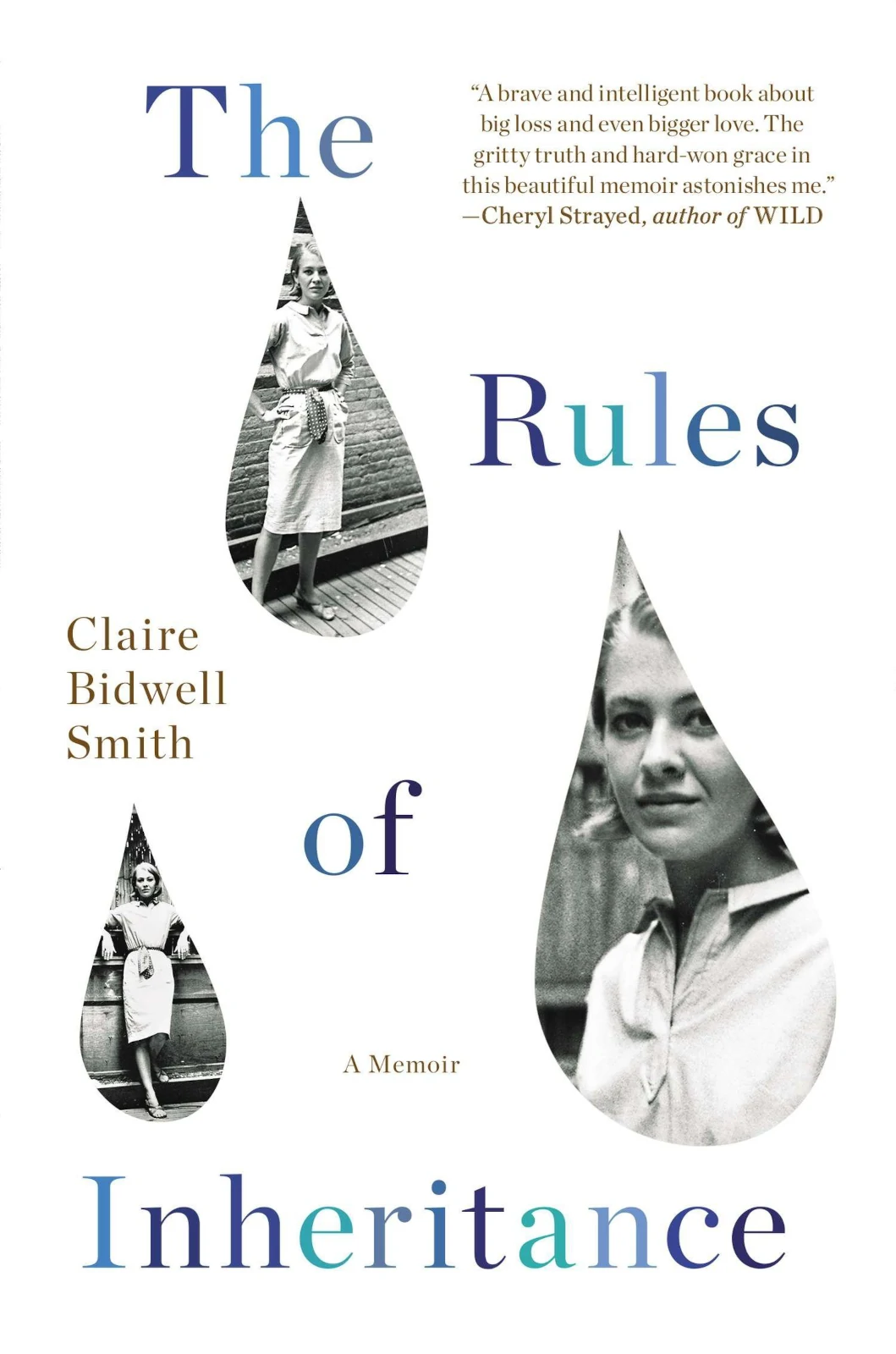

Among the many images Claire Bidwell Smith’s memoir offers, one of the most striking compares grief to a film negative, the depth of the grief standing as evidence of the love that has been lost. The Rules of Inheritance resonates with both of these themes, telling us the true story of a young woman losing both her parents to cancer and her desperate battle to get to know them—and herself—before they are torn from this world.

With a narrative that defies linear storytelling, The Rules of Inheritance introduces us to all versions of Claire: the college freshman, frightened to start anew; the broken girl, sharpened by dark tattoos and reckless adventure; the young woman, wearing the ill-fitting mask of a caretaker; and the modern-day mother, an accumulation of all the years that have been. Through each chapter we jump forward and backwards in time, slowly piecing together the mysteries of her life. However, this is not only a story of grief. When Claire is struck by the reality of mortality, she embarks on a life fueled by both the intense sadness of her loss and the wild freedom of being untethered from a normal existence. It is the latter that fills her story with excitement, creating a plot so thrilling it is worthy of the world of fiction. She travels across the world, hurling herself into dangerous adventures and love affairs: constantly jumping between new jobs, cities, and identities. And although her grief follows her everywhere she runs, it also leaves her uninhibited, allowing her to approach people spontaneously, sprinkling the narrative with intense moments of connection between strangers, bonded by secrets and truths rarely spoken, if only for a single night.

It is with great fervor that Tethered by Letters recommends The Rules of Inheritance. Studding the narrative with striking metaphors and poetic descriptions, Smith creates a soft, understated prose that seems wholly unaware of just how brilliant it is. Both beautifully crafted and thrilling to read, this debut work is a rare, unpretentious memoir that is a gift to all those lucky enough to experience it. Like the film negative that describes her grief, The Rules of Inheritance delves into the darkest parts of the human condition, and, instead of pulling us into the light, bravely exposes the beauty within our pain.

Smith on The Rules of Inheritance

Although The Rules of Inheritance has a very natural flow, the memoir was certainly not an easy work to embark upon. Smith first began it a decade ago: “I wrote the first version when I was 25 and my dad had died and it was horrible and I wasn’t at all ready. I had an agent that found my blog and I think she had this vision of marketing me as this 25-year-old literary prodigy.” Unfortunately—or perhaps fortunately considering the amazing book now gracing our bookstores—the first version of the book was rejected by every publisher they tried. After this “devastating” outcome, Smith took a break, returning three years later with what she claimed was another “shitty version,” even “worse than the first.” However, these many drafts were not in vain. On the contrary, Smith feels that those first attempts helped her to “exercise all the crap” out of her writing, leaving her with a “distilled” version of the story. “When I decided to write this one,” she explained, “it was a tour de force, I wrote it in a matter of months.”

This distilling process also brought the beautiful language to the text, allowing her to employ “the power of a few words strung together” that she had fallen in love with in works like Nick Flynn’s Another Bullshit night in Suck City. “In this book, more so than in any other,” she continued, “I felt I had the liberty to be more poetic. When I finally sat down to write it, I was really ready to write it and it just sort of poured out of me.” Although the many years of writing certainly helped her to understand her memoir, Smith said that the pivot was shifting to the present tense: “The other versions of this book were both in the past tense and they were horrible: very distant, dry, and disengaged. All the things I hate about memoirs.” But after reading Andre Agassi’s memoir, Open, Smith was inspired by the writing style so much that she restarted work on The Rules of Inheritance only weeks after finishing it. “The style allowed so much more. It put me back at eighteen, rather than being thirty-three looking at eighteen. It allowed me to access those moments and feelings in a way that I could not before.”

Another interesting change that occurred during her many rewrites was her incorporation of her romantic entanglements. Originally, she hadn’t realized that “all the boys and sex and relationships” were such an important part of her story. But when she realized that losing her parents profoundly influenced these aspects, she knew that—“no matter how scary it was”—she had to include them. “And when I did, everything else just started to come together. I think connecting with people, losing people, realizing what it takes to connect to those people, is really important to the story.” Although she originally feared that these more “trivial” aspects could overtake her main story, Smith’s constant desire to create a meaningful work, one that would be helpful to others grieving, kept her on course. “I had a mission with this book,” she explained, “it wasn’t just to write about me and my story: but this book, this version, was really born out of the time I spent in a hospice and working as a grief counselor…I really wanted to give something back and to create something that was helpful to these people…Every time I found myself writing about something that I felt was self-indulgent, I would think back to my goal: Is this helping someone in some way? And if it was, I just carried on. I read so many memoirs when my mother died. I felt so alone and confused, and so reading other people’s experiences made me feel so much less alone, and I just wanted to give that back to others. I felt that made me stay true to what I was writing.”

Smith on Publishing

Armed with a version she was finally happy with, Smith went on the hunt for an agent. After about a dozen rejections, she found someone who fell in love with the memoir, someone who insisted that Smith shouldn’t change any of it. After only three weeks, Penguin purchased The Rules of Inheritance based on a strong book proposal and three sample chapters. The editing process too was very fast paced, since Smith’s editor only asked for very minor revisions—a fact that “freaked [her] out” so badly she called her agent, thinking something was wrong. Smith laughed aloud as she regaled me with the story of her agent’s incredulity. “I guess it was just a testament to how long I had been writing it and distilling it,” she concluded, “and how I really allowed myself to be ready to write it.”

Smith does have one regret about the rapid writing time though. When she sold the memoir to Penguin, she had the first nine chapters completed, but they only gave her six weeks to write the last six chapters. Although she proved she was up to the task, she confessed she wished she had more time with the last third of the book: “Each chapter of the book, I really sat with. I wrote them in the exact order that they are in the book. I outlined the entire book before I wrote it so I knew exactly what was going to happen. In each chapter that I wrote, I would write a version of the draft and stew on it for about a week and then really go through it…it was amazing how it changed. Each chapter was like its own little world. I would have liked to do that with the last six. I feel like the language doesn’t sing as much as with the first nine.”

Smith on Writing

When I asked Smith what her process is like, her reply was one we hear from the majority of our Tethered Tidings’ authors: she tries to write every day, usually in the morning. However, Smith went on to explain that now that she has a child—barely a year old—her process has changed, since her spare time is considerably rarer. “I think becoming a mother helped me as a writer. Before that I was so apathetic and I would stew about when I was going to write. And then after I had her, every moment that I had to myself was so precious that I didn’t procrastinate and I just wrote and wrote and wrote.” By sneaking in writing hours at coffee shops early in the morning, during lunch, and during nap time, Smith got into a smooth rhythm, producing an average of one thousand words a day.

In addition to treating writing time with the respect and dedication her daughter helped her to discover, Smith recommends new writers to follow the simple rule of writing as much as possible. Even when she wasn’t working on her memoir, Smith consistently wrote a blog for eight years. “It’s so trite to have a blog,” she admitted, “it’s so stupid and self-indulgent, but it kept me writing, it kept me accountable and it keeps people reading.” Thinking back to her first drafts of The Rules of Inheritance, she added that she thought that “the trick is to be appreciative of your shitty work. People get so frustrated with bad writing days. You have to have those bad writing days to get to the good stuff. You’re not going to write a bunch of good stuff out of the gate, you have to write this bad stuff to get it out.”

Excerpt from The Rules of Inheritance

I couldn’t shake the sinking feeling that this was not the girl I was supposed to be.

No, the girl I was supposed to be would still be at college in Vermont. I would have some sweet and apologetic hippie boyfriend who I would spend the summer with before starting my sophomore year. We would drink coffee all the time and take walks in the woods. He’d have those stupid poetry magnets on his fridge and would write me little messages that would make me blush with both gratitude and embarrassment.

But, gripping the steering wheel as I made my way into the East Village that night, I knew that girl was lost forever.

She disappeared the night my mother died, and I was never going to see her again.

Three years have passed. Three years without a mother. Now I am irrevocably this girl: the one who has tattoos and drinks too much, the girl who rushes from her noontime writing classes in Greenwich Village to her bartending job in Union Square, the one who is sometimes afraid of her alcoholic boyfriend.

In three years my grief has grown to enormous proportions. Where in the very beginning I often felt nothing at all, grief is now a giant, sad whale that I drag along with me wherever I go.

It topples buildings and overturns cars.

It leaves long, furrowed trenches in the wake.

My grief fills rooms. It takes up space and it sucks out the air. It leaves no room for anyone else.

Grief and I are left alone a lot. We smoke cigarettes and we cry. We stare out the window at the Chrysler Building twinkling in the distance, and we trudge through the cavernous rooms of the apartment like miners aimlessly searching for a way out.

Grief holds my hand as I walk down the sidewalk, and grief doesn’t mind when I cry because it’s raining and I cannot find a taxi. Grief wraps itself around me in the morning when I wake from a dream of my mother, and grief holds me back when I lean too far over the edge of the roof at night, a drink in my hand.

Grief acts like a jealous friend, reminding me that no one else will ever love me as much as it does.

Grief whispers in my ear that no one understands me.

Grief is possessive and doesn’t let me go anywhere without it.

I drag my grief out to restaurants and bars, where we sit together sullenly in the corner, watching everyone carry on around us. I take grief shopping with me, and we troll up and down the aisles of the supermarket, both of us too empty to buy much. Grief takes showers with me, our tears mingling with the soapy water, and grief sleeps next to me, its warm embrace like a sedative keeping me under for long, unnecessary hours.

Grief is a force and I am swept up in it.