The Cosmic Mundane: an Interview with Helen Phillips

Words By Helen Philips, Interviewed by Dani Hedlund

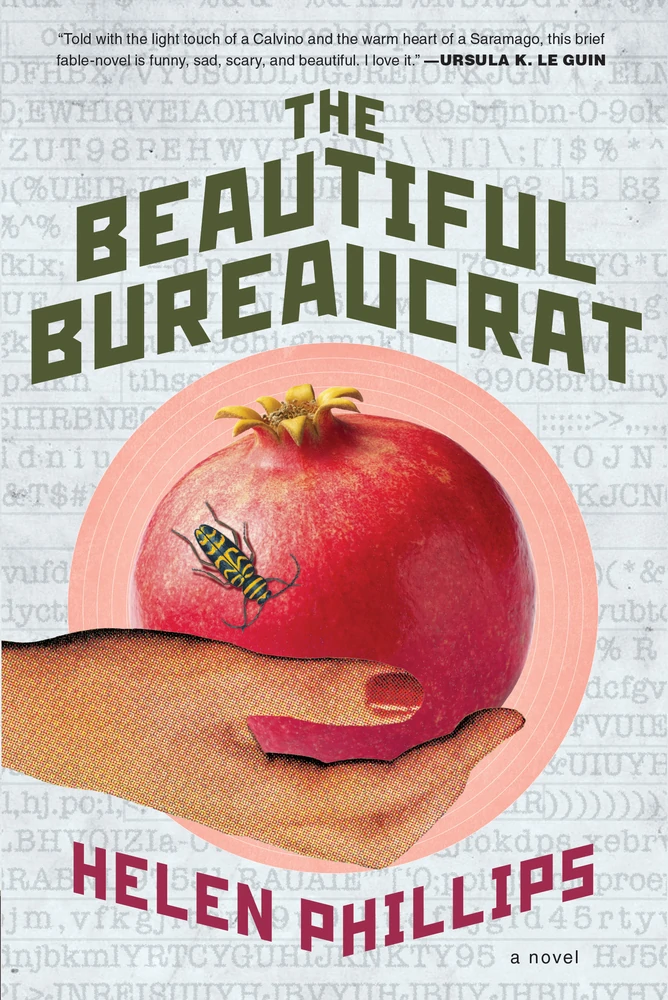

The Beautiful Bureaucrat was a strange, unconventional book and I couldn’t put it down.

Sometimes literary writers are a bit dismissive of the idea of a page-turner, because it sounds a little trashy. But, when I read a page-turner, I find it dynamic. I was curious if I could write a book that took on big themes and put them in the context of something that would have that thrill and urgency of a page-turner. It took me seven years to write the book.

The fact that you used such simple prose—it was engrossing. Those beautiful metaphors and those big ideas took me off guard because I was pulled into the plot and then suddenly, your words were jumping off the page to sucker-punch me.

There were really two things I was interested in when it came to writing the book. One was the dynamism and intrigue of the plot and themes. The other was language. When I think about the plot and the alternate world that I set it in, I’m thinking of influences like Jorge Luis Borges, Italo Calvino, Franz Kafka, Haruki Murakami. Then the other sphere of influence was writers who were really precise with language like Amy Hempel, Lydia Davis, and Jenny Offill.

At one point, the book was more than twice as long—320 pages. Both the plot and the language were affected by cutting it down. That was when I finally got the plot and the language to be potent.

Where did this outrageous idea come from?

Any idea comes from so many different sources. But the most direct, real-world source was that I had a job. It involved, during part of the year, inputting data into a database. I spent a lot of time inputting names into the database—like Josephine. I spent a lot of time thinking about the people whose names I was typing, and about their lives.

Also, the idea that somewhere, in some office, some bureaucrat was typing my information into a database. At the moments of frustration or exhaustion with my job it lightened my load or it added intrigue to the task to imagine those other people.

I also feel like a lot of my writing inspiration comes from me imagining a nightmare version of the familiar world. There’s mundane life—and a lot of life is mundane—and then I imagine a surface peeling back and something that is innocuous turns out to be threatening. I wanted the book to have something that seems mundane and then it suddenly becomes terrifying. And vise versa, something that seems terrifying, like the USPS notice that keeps following her—it seems so ominous—and then at the end it turns out to be this gift that she’s been given.

Another source of the idea: my husband and I had a time where we were moving from sublet to sublet. There was that basis in reality.

In a way this book feels like autobiography and in a way it feels like science fiction—it feels like both at the same time.

Lastly, there is the question of the meaning of life …

How did you strike a balance between giving us too much or too little? How would you describe the source of the dark creepiness of the book?

I feel like I live with such an acute awareness of death. I think that in a sense, what the ominousness is in the book is the fact of our own mortality—the way that it informs everyday existence. In this book, it becomes concrete.

How did you stick with this unconventional idea?

It took me seven years to write the book. I was pregnant when writing the second draft of it. I felt like I had a nine-month deadline.

About a week before my daughter was born I sent it to my agent. It was radio silence for three months. But I was so busy being a new parent that I barely noticed. Finally I reached out to her and asked, “Did you ever read that book?” She basically said, “This book is such a dark book that the reader won’t want to stay in this world with you. It’s too dark, it’s too heavy, it’s too gloomy, and the plot doesn’t hold together.” That was a huge moment of discouragement.

So I spent a year working on short stories and ignoring the novel. The following summer I went back to the book and realized that my agent had been right about everything. I almost abandoned the book at that point. That was where the most courage came in, because I already spent years of my life on The Beautiful Bureaucrat. I was like, “Am I going to do another draft and waste more hours of my life?” But the book still had its claws in me. I finally decided, “You know what? Screw it. I’m going to waste more of my life on this project.”

It seemed unlikely that it would ever reach publication—especially after what my agent said. That’s when I cut it in half. The plot was the last thing to come, which is really backwards. But that summer I figured out the plot and how it would all fit together.

When I was writing my first book, which is called And Yet They Were Happy (a collection of flash fiction comprised entirely of stories that are exactly 340 words), I kept telling myself, “This is not a publishable book.” It was the best writing experience I had ever had up to that point in my life. I found satisfaction and joy in my creative process that I had never before experienced to such a degree. It was very liberating to say, “This might not ever be published; in fact, it probably won’t.” With The Beautiful Bureaucrat, I had the same feeling. But it’s only by feeling that maybe it

won’t be published that I felt risky enough—that I felt free enough.

My editor, Sarah Bowlin at Henry Holt, fell in love with The Beautiful Bureaucrat right away. Within 24 hours of my agent sending it to her she had written back. She wasn’t the only one interested. I felt like I was writing something that wasn’t that marketable, so the level of interest the manuscript received was a complete shock to me.

I know that this plot will haunt me for years. I’m so glad that you went out on a limb and wrote something like this.

I felt the stakes when I was writing this book. There are so many elements of my own life in the novel. But I do tire of reading certain contemporary fiction, when I feel writers aren’t taking on the most important stuff of life.

So you wrote short form before you wrote this novel. What was that transition like?

I guess that’s not entirely accurate. I wrote three novels in my twenties that are dead to me and dead to the world. One was about the history of the New York subway system. One was about a bunch of people that were stuck in an enormous blizzard. The other was about the wife of an astronaut who disappears into space. They are full-length novels. I worked on them for years of my life. They never really came to fruition.

After abandoning those books, I wrote my book of microfiction, And Yet They Were Happy. In writing The Beautiful Bureaucrat, I wanted to combine what I did in terms of image/metaphor/language in And Yet They Were Happy with the plotting/mystery elements of my second book, a middle-grade adventure novel called Here Where the Sunbeams Are Green. (After writing And Yet They Were Happy, I had decided to give myself an opposite kind of challenge. I wanted to make sure I wasn’t just resorting to “experimental” writing because I couldn’t do the other. So then I decided I’d write a book for children, because I thought it was a really great forum to write a straightforward plot.) When I set out to write The Beautiful Bureaucrat, I wondered, “Could I do both? Can I have those images and metaphors and those big questions, combined with the suspense and characterization?”

I always write by challenge.

How did you balance wide-scoping distance with intimate writing?

The cosmic is contained within the everyday. Each minute of your life is slipping into the ether—that’s part of the human condition. In a way, the intimacy and cosmic-ness of the book imitates what a lived experience is like. The most powerful moments of life—whether they are sad moments or joyful moments—are the moments where the two suddenly flash together.

I loved the attention you gave to names. Can you talk about that?

When I was seven years old, I asked my babysitter too buy me this baby name book that was on sale at the grocery store. She was like, “Why do you need a baby name book? You’re seven years old.” But from the time I was a tiny child, I’ve always been a writer and I’ve always been interested in names.

With Joseph and Josephine, there is the fact that they have the same name. That’s working in a few ways. One is that there is a connection between them—that they are, in a sense, the same person. When I give them the same name, I’m indicating to the reader that they are symbolic, almost fairytale characters to some degree. There’s also the suggestion that they’re each an average “Joe.” At the same time, they’re the cutesy, darling couple that has the same name.

With Trishiffany there’s the humor. Trishiffany, that combination of names, it’s supposed to be an absurd, exaggerated thing about her character. Her full name also has significance. Patricia means “a patrician” and Tiffany means “gift of God.” Those things combined make sense with being a bureaucrat in this book. Maybe I’ve overdone it with the symbolism.

My original vision of the book was that the entire text of the story would be on one side and the other column would be a list of names. It would include the names of everyone I’ve ever known, which would have been creepy of me to do. But I didn’t end up doing that.

The usual paradigm of numbers is that they tend to embody a cold way of thinking about people. I love that Josephine uses Joseph’s social security number as a pet name. It was a bureaucrat thing to do and it came across so well.

When I had that job entering peoples’ names into a database, I found it to be sort of the most cold, boring task you could do. But then I took a step back and remembered that someone raised every one of these people. Structures like the IRS or the DMV—we hate these bureaucratic structures, and yet there is something humane in the act of being tallied. I read an article by Kathryn Schulz in The New Yorker and she has in it the quote, “The flipside of democracy is bureaucracy. If everyone counts, everyone must be counted.” That idea is certainly important in the book. The implication in the final scene is that everything in the universe has been counted—that there is an inherent dignity in being counted. I envision that final scene as an uplifting one, at least to some degree. That room full of files is supposed to be a glorious, dazzling image.

What is your publication history like? How did you get an agent? How did you fight through the years of rejection?

Well, my very first publication was in Highlights for children when I was six years old! It was a poem called “The Rainbow.” My first publication in my serious, adult life was in The L Magazine, which is a local Brooklyn magazine.

I have an Excel spreadsheet where I kept track of all the places I’ve submitted my work and every place that it’s been rejected from. I got in the habit of rejection so long ago. The ability to be rejected is probably the most important trait of being a writer. Writing has to be its own reward. There is no way to have success in this if you don’t take a joy in the actual process of doing it, because it’s a long road to receiving outside recognition.

I think the whole agent thing can appear very insider-y, and my agent did come through a family connection as we are from the same hometown—but I always emphasize to my students: it’s not as hard to break into the industry as it can look like from the outside. Many agents have approached me over the years following publications in certain magazines. To beginning writers: do not be discouraged. You can find agents in many ways.

My agent’s name is Faye Bender. She’s fantastic. But, she didn’t have luck sending And Yet They Were Happy out to publishers. She submitted it to a bunch of editors and it got rejected from all the big publishing houses because they said, “What genre is this?”

Then my agent stepped aside and I took it upon myself to send the book out to a bunch of small presses. I submitted it to a contest run by a small, wonderful press called Leapfrog. It was a finalist for their contest—it actually didn’t win. Then the editor called me and said, “We love your book, even though it didn’t win, we want to publish it anyway.”

There are a lot of different paths to publication. Having an agent isn’t the only way. My four books have been published by three different presses (Leapfrog, and Delacorte Press—which is a division of Random House—and Henry Holt), and each experience has been really distinct and cool in its own way.