The Writer’s Downfall: Exposition 101

If you’ve ever tried to write a story, you may have encountered the writer’s eternal problem: how do I get all the information that I know about these characters, settings, themes, and plotlines onto the page so that the reader has the context they need to fully enjoy the story?

What you’re grappling with is exposition, a narrative device that provides background information to the audience and helps readers understand the context of the story. It can be delivered through dialogue, narration, flashbacks, or a character’s thoughts. Effective exposition feels seamlessly integrated into the story. Ineffective exposition may overwhelm or bore the audience before they can get to the meat of the story.

Despite it being so necessary for stories, storytellers often find delivering exposition effectively difficult because it’s the kind of information that is much easier to tell rather than show. That’s why one of the hallmarks of a good storyteller is how well they are able to get across expositional elements in their work. It’s all about balance: without the right amount of exposition, the audience will not have enough information to understand what is going on in the story and why. How much is too much depends on what kind of story it is.

The good news is that you can effectively deliver exposition without info dumping, by utilizing dramatization and making it feel necessary to the conflict. This can be done in a number of ways, including through dialogue, narration, internal monologue, and special devices. Continue reading to get a deep dive into these techniques and more tips on exposition!

Key Aspects of Exposition

Now that you know what exposition is, let’s explore more thoroughly what components make up expositional information. This will include:

- Character Backgrounds: Any information about the characters’ pasts, motivations, and relationships in the story.

- Setting: Any details about the time and place where the story occurs, including cultural, social and historical context. Stories that take place in a time and place familiar to the audience may require only a bit of exposition, but more fantastical or complex stories will require more.

- Plot Background: Any explanation of the events that took place before the current narrative timeline.

- Worldbuilding: As discussed in our Worldbuilding 101 blog, exposition for fantasy and science fiction work, among other genres, often includes descriptions of unique elements such as magic systems, technology, or societal norms.

All creators of stories should know these details of their work inside and out. After all, you created these characters, this world, and the events that take place within it. The trick is determining what your audience needs to know in order to understand the story.

Maribel’s Tip: One rule we know works here at Brink is EKT—Everybody (in the world of the story) Knows That. If you’re about to share something that everybody in the context of the story would already know, don’t. It takes away from the realism of the story. For example, an employee would never explain their own job to their boss (unless they were being really sassy or something), because the boss should reasonably know what they do. If you need to explain this information for some reason, it makes much more sense for the employee to explain it to a new hire who doesn’t have that same information.

Types of Exposition

Exposition can be broken down into two types, which can be used by a storyteller depending on what’s needed in the story. These two types are:

- Direct Exposition: The storyteller explicitly provides background information, often through narrative summary or a character’s internal monologue.

- Indirect Exposition: The storyteller reveals background details through dialogue, actions, or events, allowing the reader to infer information.

Both types of exposition can be dramatized and used effectively in a story. What’s important is determining which type best suits your story at any given moment. For example, although the general rule of thumb is to show rather than tell, sometimes doing so might slow a story down too much. Or, it may add to the suspense, tension, or dramatization of the story to actually have that information told. Whatever your choice is, the important thing is that you have a specific reason behind why you shared the information in that way.

How to Dramatize Exposition

Now that you know more about exposition, let’s get into how you can make it fun and relevant for your audience. In general, there are four major ways to do this. We’ll outline each one and utilize examples, both good and bad, to show exactly how each of these work.

Exposition Through Dialogue

By relaying exposition through dialogue, you can make it feel actionable, natural, and important. Conversations between characters offer more than just talk—it is a way to show characterization, move the plot along, and, in this case, provide background information. However, you still want to avoid blatant info dumping. For example, poor execution of exposition through dialogue can look like:

“Alaina! My dear sister, how are you doing? Ready to pop?” said Maria as soon as she entered the room.

Alaina gave her sister a brief hug. “I can’t believe you came all the way from Upstate New York just to see me go into labor.”

Maria whipped out her cellphone to begin recording. “I wouldn’t miss it for the world, are you kidding me? We are sisters after all. I’m just so sad that Mom can’t be here.”

Alaina’s shoulder slumped. “I know, me too. Things haven’t been the same since the car accident.”

This is obviously an exaggerated example, but it does work to show you what NOT to do when utilizing dialogue to relay exposition. Let’s break down why:

- EKT: Both characters present know that they are sisters, so why would they reference it not only once, but several times over the course of the conversation. This is something that could easily be portrayed not only through actions but also through the narration (said Maria, Alaina’s sister.)

- Lack of showing: Alaina is in labor, but rather than showing that through physical cues, she simply tells Maria that she is. Again, this falls under EKT: why would Maria even be there if she didn’t know Alaina was in labor?

- Elephant in the room: This also goes back to EKT, but the elephant in the room is the mom not being there. While we have no additional context for this story, imagine that this is the opening scene. It doesn’t seem true-to-life that these two sisters, who would both be fully aware of an accident preventing their mother from being at the birth of her grandchild, would mention it in such an obvious way.

Here’s the same scene done with a little more subtlety while still getting across the same context:

Maria flung open the hospital door so hard it bounced back and nearly hit her in the face. She rushed to her sister’s side.

“Wow, you got fatter,” she said.

Alaina rolled her eyes, wincing as she sat up against the pillows supporting her. She put a hand over her swollen belly. “Gee, thanks.” Her eyes darted back to the door. “It’s just you?”

Maria gave her a tight smile and sat down on the edge of her sister’s hospital bed. “Mom’s not feeling up to it.”

Alaina blinked rapidly to clear tears from her eyes but nodded. “I understand.”

Maria grabbed her hand and squeezed it. “Don’t worry. You have me! Who else could you possibly need?”

The side of Alaina’s mouth twitched up into a smile. Even if their mother couldn’t be there, at least she wasn’t alone.

In this version of the scene, the audience gets a lot less information about exactly why the mom cannot be there. Nonetheless, they can infer that there is a reason and that it will be revealed at a moment in the story later on. Meanwhile, the mystery adds tension, keeping the audience engaged and ready to learn more.

Exposition Through Narration

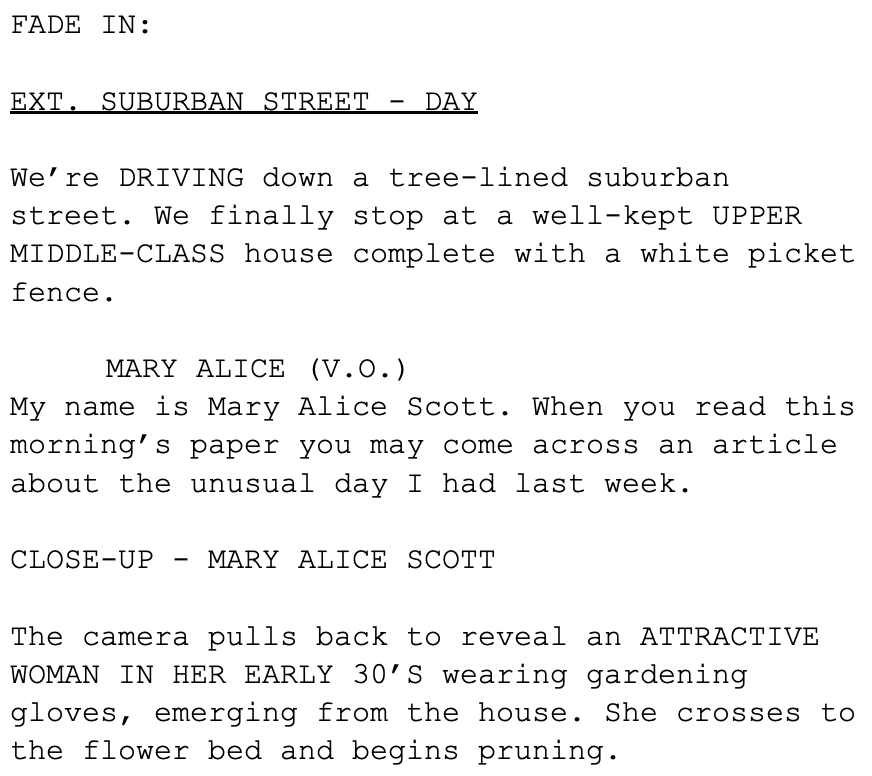

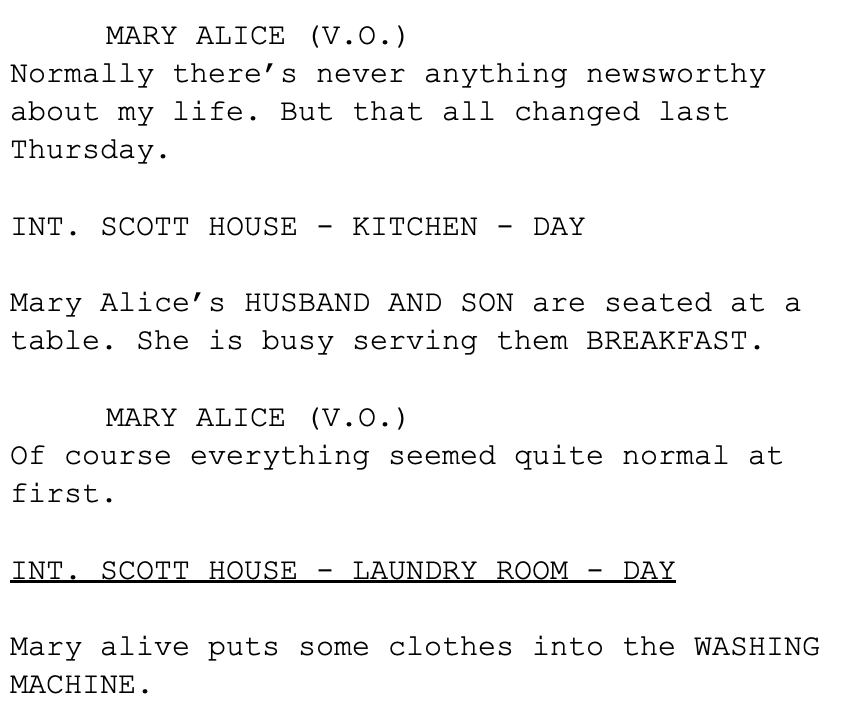

Narrators can be used to effectively express important exposition as well. It all depends on the narrative voice utilized in the story. For example, TV shows like Gossip Girl, Desperate Housewives, and Veronica Mars utilize voiceover to include narrative voice that exists somewhat outside of the story. Sort of like a third-person omniscient POV, although the voice isn’t always completely omniscient. This has the effect of providing important context and details for the story, such as giving us information the other characters don’t have yet, or allowing us to see inside their head.

Narration is also used in other forms of storytelling, of course, and the type of narration utilized to tell a story is one important overall piece of your story. A strong narrative voice is an excellent way to deliver exposition by weaving it seamlessly into the narrative flow. The important thing here is to balance showing and telling in order to keep the reader engaged. Take a look at this example from the pilot episode of Desperate Housewives (mild spoilers ahead!). You can also view the video version of this scene here—make sure to read along!

What did you notice while reading and watching this scene? How did the voiceover (and the narration happening through the actions on screen) deliver effective exposition? What did we learn about the character of Mary Alice, where she lives, who she is, and what she’s doing? This is how exposition can be delivered while also building conflict and tension, hooking the audience in without giving away too much—but preparing them with enough information for the context of the story.

Exposition through narration might also look like a typical fairytale opening: Once upon a time, there was a kingdom…—and then going on to describe the kingdom, who lives in it, and introducing our main character. This is a good way to start a story that has a lot of lore or background the audience must know to even get started. When done poorly, this kind of exposition through narration will really drag the narrative down and make the audience feel that they’re being spoon fed too much information. It’s best to use this technique with a specific purpose in mind, and sparingly.

Exposition Through Internal Monologue

Internal monologue can also be an effective way to relay background information while keeping things dramatic. A character can reveal how they’re really feeling, what they think of other characters, and what their plans are to the audience only, perhaps thinking of private information that adds to the conflict of the story. The main benefit of internal monologues are emotional stakes. While a character may not express what they’re actually feeling openly, if the audience knows, then they may prepare themselves for conflict based around the character’s true emotions further down the line. A great example of this is found in the opening of “The Pillars of Creation” by Walter Thompson:

No one’s told the bus driver about Dad, so we still get dropped off near the old house, at the corner of Myrtle and Patterson. We don’t mind. Nat and Ben get amped up on the drive out from school, squealing and shouting with their friends, bouncing on the worn leather benches. They need the walk, just shy of two miles, to settle into the cool dark side of their afternoon, so that Mom gets them when they’re at their lowest low, needing a hug and a Coke and two hours of ESPN. The whole way, they run circles around each other: pushing and yanking, pelting pinecones, kicking shins. Edward stays ten yards behind them, never looking up, as if the twins are tugging him along with an invisible string. He puts on his headphones and stares at the asphalt as he goes. The headphones aren’t hooked up to anything; he just tucks the end of the cord under his belt. He takes the “noise-canceling” thing more seriously than other people because his world is full of more noises than theirs.

Here, the narrator’s internal monologue sets off the story for us by hitting us with the most important information in the very first line: the father’s death. Then, we meet the narrator’s siblings, whose actions as described by the narrator tell us more about their ages and personalities. These little details will come back later on as plot points. The audience is engaged from the get-go because of the implied emotional circumstances and we’re looking for signs of grief and drama throughout the text.

Internal monologuing is perhaps one of the easier ways to get exposition across, but it can be difficult to get it right and not simply dump a load of information on the audience. The trick is to do exactly what the passage above does: dramatize the information and make it relevant and resonant later on in the story.

Exposition Through Special Devices

Aside from these narrative tactics, there are other ways to express exposition in a story. This could be through a letter that a character receives, a journal entry they write, or flashbacks to a previous event. You can use these devices to break up the narrative and present background information in a more creative way. Plus, these devices can serve the story and character development. For example, let’s say you use a journal entry written by a character to share expositional information. This tells us that, at the very least, the character is self-reflective. We also get the chance to take a peek directly inside their mind and voice through their journal entry.

The letters shared between Elizabeth Bennet and Mr. Darcy, and other characters, in Pride and Prejudice serve great expositional and character development purposes while also moving the story forward. For example, let’s take a close look at Darcy’s letter to Elizabeth after she (spoiler alert!) rejects his marriage proposal in Chapter 35. I won’t share the letter in its entirety here, as it’s very long, but will focus instead on a few choice moments. Firstly, Darcy writes:

“At that ball, while I had the honor of dancing with you, I was first made acquainted, by Sir William Lucas’s accidental information, that Bingley’s attentions to you sister had given rise to a general expectation of their marriage. He spoke of it as a certain event, of which the time alone could be undecided. From that moment I observed my friend’s behavior attentively; and I could then perceive that his partiality for Miss Bennet was beyond what I had ever witnessed in him. Your sister I also watched. Her look and manners were open, cheerful, and engaging as ever, but without any symptom of peculiar regard; and I remained convinced, from the evening’s scrutiny, that though she received his attentions with pleasure, she did not invite them by any participation of sentiment. If you have not been mistaken here, I must have been in an error. Your superior knowledge of your sister must make the latter probably. If it be so, if I have been misled by such error to inflict pain on her, your resentment has not been unreasonable.”

Here, he references Elizabeth’s accusation that Darcy was the one who stopped the romance between Mr. Bingley and Jane, Elizabeth’s older sister. We learn information that we did not know before: Darcy had a conversation with another character, who implied to him that Bingley and Jane would get married. This expositional information is important because it provides context for Darcy’s later actions, which he explains. We also learn several important things about Darcy’s character that Elizabeth and the audience didn’t necessarily know before: he is a loyal friend in trying to protect Bingley’s feelings and he is not afraid to admit fault.

The letter goes on to explain what actually happened between Darcy and Mr. Wickham, which is also expositional information. The delivery of this information is simple but telling. While it could be considered an info dump under normal circumstances, Jane Austen has set it up so that it doesn’t feel as such. Here’s why it works:

- Set precedence. In Pride and Prejudice, the letter from Mr. Darcy explaining himself follows several others, setting the stage for letters to be important pieces of information within the story. If this were the only letter in the entire novel, it might come off as a deus ex machina and work much less well.

- Expand on characterization. This letter tells us so much more about who Darcy is as a person, unfiltered through Elizabeth’s point of view since the words are his own. We’re able to see firsthand how many of Elizabeth’s conceptions of him spring from his struggle to communicate with her—as well as, of course, their shared trait of pride and their personal prejudices against each other.

- Amplify existing tensions. The information provided in the letter adds additional drama to pre-existing relationships, making the reader eager to see what will happen next. This ensures that instead of feeling like an information dump and deflating the stakes, it raises them in anticipation of further scenes.

In Summary: Four Tips for Effective Exposition

Now that you know different ways to dramatize exposition, here are a few general tips for tackling it in your story:

- Show, don’t tell. Incorporate exposition into the story through actions and dialogue rather than lengthy explanations.

- Keep it relevant. Ensure that the information provided is essential to the plot and character development. While you may know more information that the audience doesn’t, if the audience doesn’t need to know that information, you can keep it to yourself! As the creator, you’re always going to know more than your audience.

- Spread it out. Distribute exposition throughout the narrative rather than dumping it all at once. This prevents the audience from getting bored or feeling that the story is dragging.

- Engage the reader. Make exposition interesting by adding conflict, tension, or mystery, as we’ve outlined above.

Keep these tips in mind as you approach writing exposition to help your story stay afloat!

Exercise

Write a scene in which you share crucial background information about a character only through one of the above tactics: dialogue, narration, internal monologue, or special devices.

Get Off to a Great Start With Your Story

With these techniques to express exposition in your story under your belt, take a stab at each one when writing your next story. Remember, exposition is best delivered through dramatization and techniques that serve more than one purpose in the story. Of course, there will always be times when it is more efficient to share background information directly, but these are generally far and few inbetween. Don’t let exposition scare you away from writing your best story. In your first draft, let all the information you know flow free and then go back to see how you can better express it on the page.

Looking for more writing tips and advice? Check out the rest of the Facts of Fiction series to learn about the storyteller’s journey from beginning to end.