He can see everything but her. The rest of the room exists clearly in his mind. The walls painted a sunshine yellow. The sturdy, handcrafted oak bedroom set with dovetail joints and darkly stained grain. The paper birch with the coin-shaped leaves seen out the second-story window. On the night table sits a clock, the red numbering of which reads 7:00 a.m. The digits blink as the alarm sounds. But he doesn’t reach out to silence it. He doesn’t open his eyes.

Next to the beeping clock is a framed portrait of his family. They show their teeth in smiles. They wear matching jeans and white-collared shirts. They stand in a flower-filled meadow. They lean and weave their arms together in such a way that they appear to be holding each other up. He can see his daughter. He can see himself. He cannot see his wife. She might as well have been scissored out of the photo, scrubbed out of his mind, a raw vacancy.

He wants this image to remain true, but it no longer is. He wants to roll over to face the opposite side of the bed, where Pamela ought to be sleeping, her body denting the mattress, but she is not there. Something else is.

The screeching of his alarm seems to grow louder. His veins throb in time with it.

If he looks, that would mean acknowledging what he has to do. A muscle in his jaw pulses. He barely breathes. Morning light warms the bed but he feels cold.

When he finally opens his eyes, he does not scream or even flinch away. He simply stares back with an ugly resignation.

The sheets and the comforter are as white and clean as soap. But the thing that shares the bed with him is not. It is dressed in filth, clotted with what might be dried blood and grave dirt. Sticks and dead leaves cling to it. The fabric of its wrappings might have been stitched out of the night itself and buried for a thousand years. Its face is hooded, so he cannot see the features hidden within, but the shadow there is so profound that he feels he is looking into a cave littered with bones that goes on for an unguessable distance.

The alarm continues to sound, but he no longer hears its noise in intervals, only as a single, uninterrupted, high-pitched scream.

The showerhead hisses and Sam stands under its needling spray. He splats shampoo into his hand and fingers it onto his scalp until bubbles froth up. He scrubs himself with a sponge.

Through the marbled glass, he can see the thing standing in the bathroom, watching him. Even when he doesn’t look directly, he can feel it, like a bruise at the edge of his vision.

The room swirls with steam. When he finishes rinsing off, he twists the knob and remains in the stall until the dripping stops.

He slides the door open and the cold air tightens his skin. He reaches for the towel on the bar, only a few inches from where the thing stands.

“Leave me alone,” he says.

While Sam dresses—pulling on khakis, buttoning a gingham shirt—he can hear his daughter downstairs making them breakfast.

Their kitchen is stainless steel and white quartz; he can imagine Ella down there, snapping on the stovetop burner. The gas flares in a blue ring that matches her dyed hair. She is seventeen and her fingers are busy with rings, including one of a horned skull. She bought it at a vintage shop, along with everything else she is wearing: the shredded jeans, the Korn T-shirt with the cutoff sleeves, the gray grandpa cardigan. That’s not how she looks in the family portrait. She has changed since then.

Everything has changed.

The window over the sink offers a view of the neighborhood—mostly neocolonials and Tudor Revivals set back on three-acre lots. Ella is likely looking out of it now. The sun won’t have burned off the mist yet, and the Land Cruisers and Teslas and Range Rovers will cut through the gray scarves of it as they roll off to work and school.

She will be cracking six eggs into a bowl. With a fork, she’ll stab and stir the yolks. She will drop a sizzling square of butter into the hot pan. The eggs will soon follow and she will let them sit a moment before roughing them with a wooden spatula.

The toast pops. She scoops the scrambled eggs onto two plates. And she carries it all to the round table tucked into the kitchenette—just as Sam pounds down the stairs and enters the kitchen with a leather messenger bag strapped to his shoulder.

“Hey,” she says.

“Hey.” He heads directly to the coffee maker. The carafe is burbling, nearly finished brewing. From the cabinet, he pulls down a mug and splashes it full. He blows the steam off it before taking a delicate sip.

Ella says, “You have to have breakfast.”

“I will.”

“Come sit.” She uses her foot to nudge out a chair for him to occupy.

“You’re the best, but…” His words trail off as he recognizes that his seat is occupied by the thing. It looms only a foot from his daughter.

She scrapes butter onto the toast. Her knife slows when she notes his widening gaze.

“No!” he says.

The scream startles his daughter. She drops her knife with a clatter. “What?” she says, standing up. “What’s wrong?”

He hurries to her fast enough that coffee splashes over the lip of the mug, burning his hand. He drags her from the table and puts his body between hers and its.

“Dad?” Ella says. “What are you doing?”

“I’m sorry,” he says. “I just… I wish I could sit down, but I have this stupid meeting. With the hospital board.”

Her face twists with confusion. “You can’t sit for five minutes?”

“Not today. No. But.” He scoops up the plate she made for him. “Thank you for this—I’ll eat it on the way.”

He rushes to the mudroom, trips over her skateboard and curses, and Ella calls after him, “Are you okay?”

“Fine. I’m fine.”

“What about tonight?”

“What about it?” He tucks his coffee into his elbow and rattles the knob and opens the door to the garage. “What?”

“Mom,” she says in a pleading voice. “We’re supposed to go see Mom.”

He pauses in the doorway, already halfway gone. “Right. Yes.”

“It’s her birthday.”

“I’ve got to… do some things first,” he says. “But we’re going to make that happen.” He nods to himself. “Of course we are.”

He pulls the door shut behind him so roughly the house shakes.

His eyes flit between the road and the rearview mirror. His house retreats into the distance. The neighborhood blurs past. He drives a Volvo station wagon. He bought it after Pamela’s accident—after her car plunged off the road and hit a tree, after her unrecognizable body was found mangled inside—because it had a steel frame and a top safety rating.

His breakfast plate is balanced on the dash and when he rounds a corner, it slides from one side of the car to the other. It is about to sail off, soon to flop onto the floor, when he catches it.

He slows now, easing the brake. The speedometer drops from sixty to twenty-five. He feels far enough away from home to settle his breathing.

In the backseat, the thing sits, blacking out most of the rear window.

“Not her,” he says. “Okay? Never her! Never!”

The thing does not respond. It is silent and watchful.

“You’re hungry?”

He pulls the plate down, balancing it on his lap. He picks up a piece of toast and chucks it into the backseat.

“Then eat!”

He hurls the rest of the plate over his shoulder. “Eat!”

But the thing does not respond, even as the toast bounces off its shoulder, as the clumps of eggs ooze down its chest.

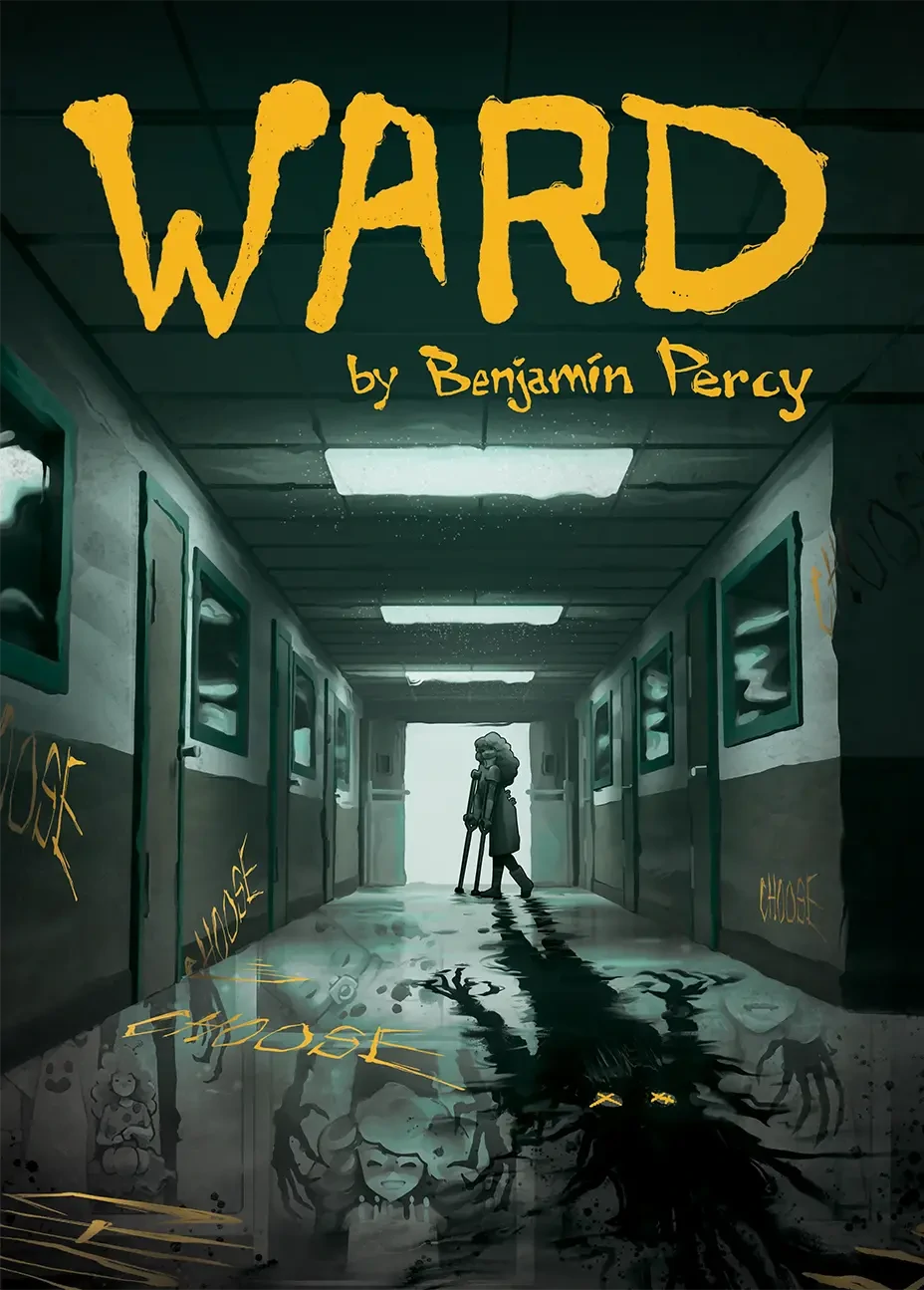

The recovery ward has a particular smell—an ammoniac tang—that Sam has come to associate with fear. Everyone here is close to death. The lights are always dimmed to a twilight glow. The nurses speak in hushed tones. The orderlies try not to rattle their carts or squeak their shoes. You don’t hear much in the way of laughter. Music or even the mutter of a television is rare.

The few hours a day that patients are awake, their eyes appear filled with mist. Sam wears a bleach-white lab coat and sometimes patients will rise out of their anesthetic blur and say, for a second there, they thought he was an angel. “No,” he says. “That, I am not.”

The boy is named Luke. He has dark, hollowed eyes and a naked head that is yellow- skinned where it isn’t bandaged. Some blood stains through the gauze. He lies in a bed with plastic guardrails. Fluids drain in and out of him.

His mother sits next to him, holding the boy’s hand with both of hers.

Sam approaches with a gentle smile. “Hi there.” He checks the dry-erase board and sees her name listed there. “Tina. How are you holding up?”

She gives him an ugly laugh. “Not great.”

“I understand.” He picks up the chart from its plastic sleeve on the wall and consults the nurse’s notes. Then he rolls a stool close to the bed. “What can you tell me about Luke?”

“He was awake for a little while. He had some ice chips.” She picks up a Styrofoam cup that now sloshes with water. “Maybe an hour ago.”

“Did he say anything?”

“He said mom. That was all he said. Just . . . mom.”

“That’s good. This early out of surgery, that’s kind of remarkable, actually.” He scratches down a few notes on the chart.

“I did this to him.”

Sam gives her a double take before his forehead wrinkles with concern. “I know this is hard. Don’t make it harder by saying things like that.”

Her voice cracks in ten places when she says, “It’s in my family. It’s in my blood. I had it too.”

Sam tucks his pen into his breast pocket and gives her a steady look. “And you’re still here. Just like he’s still here.”

She nods, trying to convince herself. “It just . . . feels like death is so close. I don’t know how to feel? Should I feel happy that he’s alive? Or sad that he almost died? He feels like he’s in-between, and I don’t want to believe in something if it’s going to get taken away.”

Sam’s gaze rises, taking in the black ragged thing now looming behind her. “Death is always close,” he says in a hushed voice. “To every one of us.”

The thing lifts an arm—and a long, rotten, gray-fingered hand appears from beneath its sleeve. It is reaching for the boy. There is a creaking, as if of old ropes on a ship.

Sam raises his voice when he says, “But your son isn’t going to die today. I can promise you that. Not today.”

Slowly, the hand of the thing withdraws.

Sam shouldn’t be walking so fast. When he walks fast, he makes people nervous, because it means that something is wrong. But he doesn’t have much time. He moves down the corridor of the recovery ward. The walls are the color of spoiled milk. The fluorescent lights pale every complexion.

He glances into one room—and sees the thing. It is in the next room as well.

And the next.

And the next after that.

It stands beside the beds of the patients, but it watches Sam. Because it wants him to choose.

A voice calls out to him—“Dr. Volk?”—and he nearly shrieks in response.

A woman named Carolyn—with purple braids and matching fingernails—stands from the desk at the nurse’s station. She has a stack of papers in her hand.

“Sorry,” Sam says. “Yes—what is it?”

She gestures with the papers. “Need you to sign off on a dozen or so scrips. And there seems to be an issue with a DNR. Also, Room 13’s daughter called and—”

“Can I check back in with you? In, like, five minutes?” He holds out a splayed hand for emphasis. “Five.”

“Sure. Yeah. Everything okay?”

He waves back at her apologetically when he continues down the hall.

“It will be. Soon.”

On the first floor of the hospital, Sam pushes open a door a crack and peers out the stairwell. The hallway is empty, except for an orderly who carries an armful of blankets and hums a nonsense song. Sam waits for him to vanish around a corner and then he enters the corridor fully and creeps toward the OR.

He pushes through the double doors into the observatory. He can hear the surgeon chatting in the next room, getting prepped, and he can see through a window an old man lying on a stainless steel table. He is naked except for a strip of tissue paper covering his groin. Lights blaze down on him. His mouth hangs open, revealing a serrated line of teeth. He is thin with loose papery skin.

A nurse in a floral smock smears iodine across the old man’s abdomen. Some lines have been stenciled there, indicating the site of the surgery, likely a gallbladder removal.

The nurse finishes his work and departs the room.

Sam can sense the thing beside him. Its fabric shifts like the rustling of dry leaves.

“Him,” Sam says, tapping at the window. “I choose him.”

Minutes later, after the surgeon washes her hands and fits on her scrubs cap and snaps on her latex gloves, she backs through the door that leads to the OR. Here, she almost slips. Because the floor is wet. So are the walls, and the ceiling, everything splattered with blood. The surgical lamp drips like a molten chandelier and burns with a bordello-red light.

There isn’t much left of the old man on the operating table. Some broken ribs and what might be a femur spike out of torn meat. A damp yarny mound of intestines unwinds and plops onto the floor.

Back in his recovery ward, Sam keeps looking behind him. Here is a robed patient exercising with a walker. Here is a custodian pulling a trash bag out of a can.

He tries one room—and observes a man sleeping soundly. He checks in another room and finds a woman sitting by the window, staring out at the parking lot. He pokes his head into Luke’s room next. The boy is awake, and his mother is spooning applesauce into his mouth. He eats greedily and some of it sludges down his chin.

Sam feels his muscles loosen. He takes a deep, cleansing breath. The thing is gone. For now.

He heads toward the nurse’s station. Carolyn pops her eyebrows as he approaches. “Everything good now? Ready to talk?”

“Yes,” he says. “Everything’s great.”

At Valley Grove Cemetery, the grass is mown in tidy stripes and shadows lean and pool between the old oaks. Sam and his daughter stand over a grave. The stone reads “Pamela Volk.”

Sam holds a bouquet of wildflowers. Ella has her skateboard tucked under her arm.

“I can’t believe it’s been a year,” she says. “It feels like no time.”

“It feels like forever for me,” he says.

“I remember how she hated lilies. She said lilies smelled like funerals. So…”

“So.” Sam makes a kind of toast with the bouquet before laying it down.

“So no lilies, Mom,” she says. “Happy birthday.”

Cicadas wheeze. A breeze rises and ripples through the leaves, curling up their silvery undersides. A cardinal wings by in a red flash.

“I,” Sam says, clearing his throat. “I remember how she used to call for us. ‘Sam and Ella,’ she’d say. But fast, like: ‘Salmonella.’ People would always look at her funny when she did that.”

A beat of silence passes before Ella says, “I remember how she would always make you split your order at the restaurant. So she got to try two things.”

“I remember,” Sam says, “how she used to put her feet on me when she got into bed. Her feet were always freezing cold, even in the summer.”

“I remember how she would quiz me constantly on math facts. Nine times seven, twelve times eleven; that kind of thing.”

“I remember how she loved to sing along to the radio but always got the lyrics wrong.”

“I remember how she tried to ride my skateboard in the driveway and broke her wrist.”

Sam says, “Then she made everybody sign her cast, so she looked like a twelve-year-old.”

Ella looks up at him. “Dad?”

It takes a long time for him to meet her eyes. “Do you ever wonder if she…” Her face flinches.

“Do you ever wonder if she killed…”

He can’t hide the sharpness in his voice when he says, “What?”

“If she killed herself? Do you wonder that?”

“Oh,” he says. “I thought you meant—no. No, I don’t think that. Why would you say that? She died in a car accident.”

“But what if—”

“No.”

“She would get so sad sometimes. And scared. Don’t pretend like you don’t remember. She would go be alone, sometimes for days, before coming back.”

“Ella. Please.”

“The last time I saw her, when she grabbed her keys and left, she looked like that. I called out to her. I said, ‘Mom, wait!’ but she wouldn’t even look at me.”

“Your mother loved us, and we loved her. That’s what we should be focusing on. The good parts.”

“But she had bad parts.”

“Everybody has bad parts, and when you love someone, you accept that as part of the deal.”

Ella takes in the gathering shadows of the woods. “It’s just… sometimes I get this feeling… this feeling like something dark is close. And I know… I know sometimes that stuff is inherited and…”

“Ella,” he says and pulls her into a hug. “Come here.” Her body trembles in his arms.

“You know what I used to say to your mom?”

Her tears dampen his shirt at the shoulder. “What?” she says in a quiet voice.

“When things got dark, I’d say, ‘I want you to put all of that poison in me. I’ll soak it up. I’ll eat it for you. Because I can take it. I can take it.’ I’d hold her just like this, until she calmed down. Until she felt better.”

Ella sniffs. “Did it work?”

“You tell me. Whatever pain you’ve got, just give it to me. I can take it. I promise.”

She pulls away from him and roughs some tears from her eyes. “Thanks, Dad.”

“Did it help?”

“It helped.”

He pushes back her bangs and kisses her forehead. “That’s what family is for. We carry each other.”

She motions to the grave. “I feel like we should—I don’t know—bake a cake or something.”

“Your mom loved Dairy Queen Blizzards. Should we go get one? I kind of feel like one.”

“Yeah.” She tips her head into a nod. “Yeah, that sounds good.”

Then she drops her skateboard onto the asphalt path and jumps onto it. “Race you!” she says. “Loser buys the ice cream.” She pumps her leg once, twice, rolling swiftly away.

He gives chase, yelling, “Oh, it’s on!”

And with that, they leave behind the cold stone and the bright flowers and the steadily darkening woods.

At Dairy Queen, on the outdoor patio, they eat cheeseburgers and dip their French fries in ketchup. Ella turns her chocolate Snickers Blizzard upside down, as a test, before spooning into it with a laugh. When a crow hops close, she tosses it a fry and asks it to come home as her pet.

Sam talks to her but feels as if he is only half tuned-in to the conversation. He pokes at the salty crumbs in his basket without remembering having eaten a single bite. He keeps looking over his shoulder, hunting for something that isn’t there. The sun is dying on the horizon.

At one point, Ella has to say, “Dad,” three times before he says, “Sorry. What?”

“I was asking if we can look at photos when we get home.”

“Yeah. That sounds nice.”

A half an hour later, they’re in the living room, digging through cardboard boxes and stacking albums and scrapbooks on the coffee table. Ella curls up on the couch, and Sam finds his recliner.

She says, “I used to think it was weird, how Mom insisted on printing up all our photos at Walgreens, but now I’m glad. There’s something more real about them this way.”

They flip through baptisms and camps and soccer games and picnics and vacations.

“Look at this one,” she says and rotates the album to show off a photo from Yellowstone. The three of them stand before a steaming mud pot, pinching their noses. Pamela had a smile that seemed to reach all the way to her ears. Her hair was the color of sunlight. She complained constantly about the lack of pockets in women’s clothing, so she bought men’s shorts and shirts and tailored them to fit her. That’s what she was wearing in this photo: pockets. So many pockets. She hid so much in them.

Sam says, “You wouldn’t stop complaining about the rotten egg smell. So we made a game of it. It was our goal to find the stinkiest attraction in the park.”

“Mom was convinced I was going to get eaten by a bear.”

At the bottom of a box, Sam finds a black book that appears more like a journal. The spine has the ribbing of vertebrae. He flips it open randomly— somewhere toward the back—and finds a photo of Pamela.

She is a teenager with a perm that looks like it weighs twenty pounds. She holds a volleyball and wears a jersey that advertises her favorite number: seventeen. But—and here’s the thing that makes him lean forward—there is a black figure roughly Sharpie-d into the background.

He flips back one page, and then another, and another after that, and finds the same. The thing is with her. At the county fair, when she won a blue ribbon for her sheep. At Christmas, when she showed off a new sweater beneath the tree. At a birthday party, where she puffs her cheeks to blow out the candles. There are words scratched onto the pages too: “Choose,” “Choose,” “Choose,” “How can I choose?” “I can’t choose.”

And: “Will it stop?”

And: “What if I give myself to it?”

There are also newspaper clippings—of car accidents, farm accidents, a string of homeless murders. Here are ten obituaries, nine of them in hospice, one of them a seemingly healthy teacher.

And then—Sam keeps flipping back, back, back—on the very first page of the album, there is a photo of her in a church. She stands with her mother. They both wear black. Their faces are dour. On the altar is a coffin with lilies all around it. A large photograph of a middle-aged man is placed on a pedestal nearby. The thing is Sharpie-d into the background here. “Dad left,” she has written in the margins. “And it chose me.”

He realizes that he’s been sucking his breath in and out of his teeth when Ella says, “What’s wrong?”

Sam slaps the book shut and blinks at her rapid-fire. “Nothing. Just getting tired.” He rises, taking the book with him. “Think I’m ready to say good night.”

He startles briefly because his reflection ghosts the glass of the nighttime window, and he pulls together the curtains, blocking out the night.

When the red numbers on the bedside clock turn over to 7:00 a.m., his alarm sounds and his eyes snap open. The family portrait on the night table stares back at him. The three of them, in matching outfits, smiling in the sunlight. It’s almost disgustingly wholesome. He’s known for a year that it was no longer true. But now he recognizes that maybe it never was. There might as well be a black wraith scribbled into the background, a fourth member of their family.

He punches off the alarm. In the hush, he rolls over to check the other side of the bed. He finds it empty. A sigh filters through his nose.

He throws aside the comforter and climbs out of bed—only to find the thing standing between him and the bathroom.

“No.” He retreats until the backs of his legs strike the mattress. “No, I gave you what you wanted.”

The thing continues to observe him with its dead abyss of a gaze.

“It’s too soon. Leave me alone, goddamn it.” The thing waits.

“Is it because he was old? Did that not . . . satisfy you or something?”

The thing watches.

Sam shoves his fists against his eyes. “Jesus, Jesus, Jesus—I can’t keep doing this.”

When he pulls his hands away, his vision is blurred red, and it takes him a moment to find his focus again. The thing is now even closer, swallowing up most of his vision, as if night has returned suddenly to his bedroom.

“Get away!” Sam bashes into his night table, knocking over the framed photo, shattering the glass. The thing speaks in its rusty wheeze of a voice: “Choose.”

Sam dresses in a rush. He doesn’t bother combing his hair. His unbrushed mouth tastes a little like the ammoniac air in the recovery ward. He chases his way down the stairs and peers around the corner of the kitchen and says, “Thank God.”

Because his daughter is gone. She has left him a bagel with cream cheese and raspberry jam on it, along with a burbling carafe of coffee. Next to his mug is a note—written in her spidery script—that reads, “SAT prep before school. Had to go. Eat your breakfast or else! Love, Ella.”

He feels a cold trace in the air. To his right is a shadow where one wasn’t before. Every part of his body stiffens except the note shivering in his hand. “Come on then.”

Sam normally pays little attention to his neighborhood. It is a place he drives through on the way to someplace else. Now he swings his head back and forth, intensely studying lawns and garages, looking for someone who might be a suitable candidate.

The thing waits in the backseat. He tries not to look at it, but in the same way that staring at a light can stain your vision, so does its darkness. He sees it even when it is out of his range of vision; its contamination is always with him.

A man walks down his driveway to fetch a newspaper. His bathrobe hangs open and his belly swells out of it. He has a ruddy face, appears to be in his late forties, and might be sixty pounds overweight. Sam looks at him the way he would a patient and decides he likely has some combination of diabetes, high cholesterol, and hypertension—a prime candidate for a stroke or heart attack.

He feathers the brake, slowing the car.

The man snatches up the newspaper, unfolds it, and reads the headline. But he soon senses the Volvo and a stare seals between them.

Sam licks his lips. “Okay. Okay, how about—”

Just then the front door of the house opens and a boy and a girl run down the driveway. They wear backpacks and carry lunchboxes and might be in first or second grade. They grab hold of each of his legs and he ruffles their hair while giving Sam a hard look.

Sam stomps the gas and speeds off.

An ambulance is parked in the middle of an intersection, its light bar flashing.

Two squad cars are also present and the officers redirect traffic. Flares burn. Their brightness draws Sam’s gaze from three blocks away. “Give me something. Please, please, please,” he says, and the Volvo picks up speed.

At the same time, the thing leans forward, and places its rotten hand on the headrest. Its nails tear the leather with a squelch.

Sam leans forward, whimpering, trying to avoid its touch.

“Choose,” it says.

“Just be patient. Just give me a goddamn minute.” His words come out as nearly a scream.

Some sort of accident has taken place, as a sedan is parked crookedly. The windshield is shattered and bloodied, and the asphalt is littered with sparkling jewels of glass. He can’t see much, in his hurry, but the EMTs are rolling a stretcher, a stretcher with someone belted to it, toward the rear of the ambulance.

“There!” Sam says. “There! Go! Just leave me alone. Leave my family alone.”

The Volvo comes to a rocking halt. He jams the gearshift into park and rushes out of the car without even killing the engine or shutting the door.

When he looks back, he finds the backseat empty.

He chokes out a laugh and spins in a dizzy circle and runs a hand across his face. And then pauses. His hand begins to tremble and falls to his side. “No.” He walks—and then jogs—and then sprints forward. “No!”

One of the officers tries to stop him, holding up his hands. “Sir, please step back!”

“I’m a doctor,” Sam says, dodging past him. “I’m a doctor!” He nearly falls, sliding on some broken glass, and then he is upon it. The skateboard. His daughter’s skateboard, with the pink wheels, its bottom plastered in stickers. It’s been splintered beneath the sedan.

“Not her! Anyone but her!” He keeps running, breathless, toward the rear of the ambulance, where the EMTs heft the stretcher. “Take me! Take me instead! Take me!”

In the rear of the ambulance, Ella lies on a stretcher. Her arm and cheek are speckled with glass. Her hairline is split open, revealing a slick gray stripe of skull. One of her legs bends crookedly in the wrong direction. The EMTs hover over her ruined body, checking her vitals. Her breath is shallow and her pulse is elevated. She won’t respond to their voices as they call out to her.

But they are soon interrupted.

Outside there is a sudden screaming. Of one voice, then two, then three, four. They make the agonized music of those who have witnessed something horrible.

One of the officers rushes to the rear of the ambulance. His face and uniform are freckled with blood and he gasps as if he has run a long distance. “Get out here! You’ve got to get out here!”

When Ella finally wakes up, she doesn’t know how much time has passed or where she is or what’s happened. Her thoughts are muddied from pain and medication. She is in bed. She knows that. She is in bed and her leg is hanging from an elevated harness with screws burrowing into her skin. One of her eyes is half-lidded, crusted and bruised. Her head is mummied with bandages and when she looks one way, then the other, it takes her vision a second to catch up.

A heart monitor beeps with the regularity of a slow alarm. There are cards and flowers and stuffed animals on a nearby table. A hospital—the word comes to her gradually—she is in a hospital.

She searches the room further and notes a figure standing in the corner. “Dad?” And then she realizes it is not a person, but a manifestation of shadows, like the night incarnate. “Hello?”

The thing approaches, not walking, but gliding.

“Who are you? What do you want?”

Its voice gasps out a single word: “Choose.”