“You’re going to love it here, Dad,” the stranger says. She has blond hair, thick eyebrows, and a sharp chin. My chin. My daughter? My sweet little . . . Abigail? Rachel?

“I’m sure I will, sweetie.”

Her eyes green like my wife’s. Always wet, like drowned emeralds. “I know it doesn’t look like much, but the doctors here seem really nice. They’re going to take good care of you until you feel better.”

“Better?” I say, dumbly.

She laughs though the smile doesn’t reach her eyes. “Better,” she says, as if the word were a talisman. “Then we can bring you home.”

“Home,” I mouth the word, loving the way its roundness fills my mouth. “That sounds really nice, Abby.”

Her eyes well up and she squeezes my hand. “It’s Victoria, Dad.”

I smile through the heartache. “Right.”

I blink and I am sitting alone, the light through the window now the soft gold of evening.

“Vic?” I cry for my daughter, eyes darting to the corners of the empty room.

My new home is a ten-foot by ten-foot box with a window overlooking the yard. My bed is a twin, topped with a king-sized comforter. There is one photo on the wall. In it, an unfamiliar man in a tuxedo has his arms wrapped around a woman in a white gown, his hands resting on the luminous curve of her pregnant belly. They both smile at me.

“That’s me?” I say aloud, standing and hobbling closer, my knees aching. Why do they ache? That’s right, I’m old! The man in the picture is handsome and young though, his eyes full of life.

Excited, I take the picture from the wall and move to the bathroom mirror.

I am fatter than the man in the photo, a rounded gut hanging over my waist. Gray hairs poke out from my ears, and my face looks like a melted wax caricature of the man in the photo. I touch the stubble on my chin and the loose gizzard flesh that hangs beneath.

“I’m old,” I say aloud, though the delight is gone.

I put the picture back on the wall.

I begin to weep.

“Think of it like getting lost in a fog,” a woman tells me. She is middle aged, with a thick jaw and a snake’s nest of curls atop her head. She is sitting in a chair in front of me, jotting notes on a clipboard.

I am sitting on the edge of my bed, and I am wearing a different robe than I was a moment before. My face is dry.

“How long have I been here?” I ask.

“You were checked in four days ago,” the woman responds. “Henry, are you here with me?”

Four days? My God, I lost four days?

“Yeah,” I croak, throat dry. “I’m sorry, what were you saying?”

The woman studies me over the edge of her cat-eye glasses. “The fog metaphor. We’ve found it eases the transition into and out of the fugue state. The jumps, the missing time, those will only get worse. But with the right attitude, we can make the process as comfortable as possible.”

“Fugue state?”

She nods tiredly. “Imagine an entire world covered in a deep, impenetrable mist—you’re lost in it, but you can see a mountain. We’ll call it Mount Clarity. Every day, your brain tries to climb that mountain. Some days, you won’t succeed. And some days you will climb all the way to the top and be your old self again. The important thing to remember is that it won’t happen every day—it’s okay when you don’t make it to that peak. We’ll be here to take care of you until you’re back with us.”

I open my mouth to thank her; only a groan comes out.

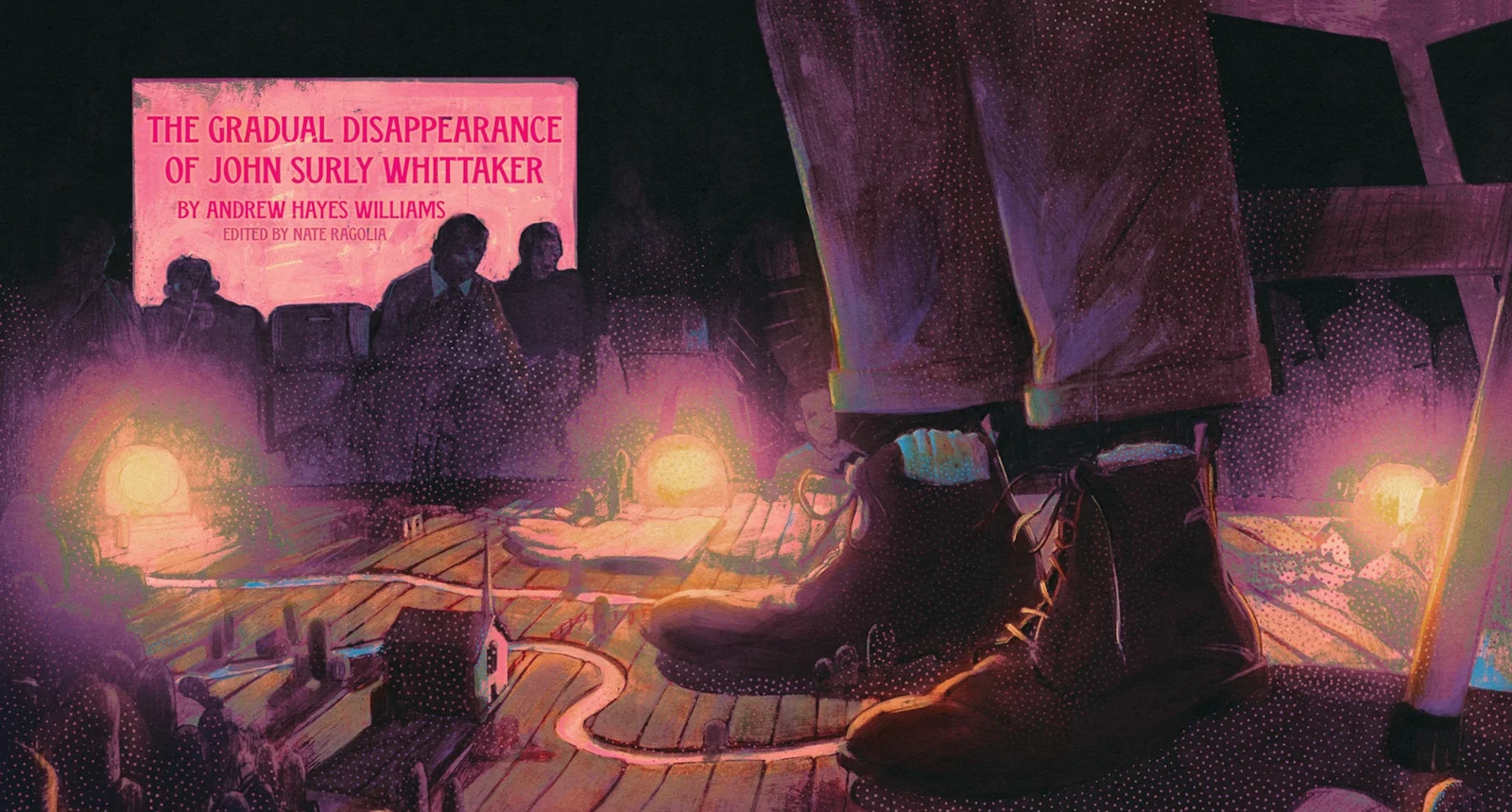

When I dream, I am in that fog. It is colder than I imagined, a thousand icy fingers worming their way into my skin.

I see Mount Clarity in the distance, and I run towards it, eyes fixed on that sharp spire rising above the white blanket. There are others here too—shadows racing, scrambling up the slick sides of the mountain.

There is something in their faces that I don’t like, a mindless terror in the way they look over their shoulders. They screech like animals, growling and crying. Their fingernails scrape against stone until they crack off in bloody splinters.

“The fog isn’t empty,” a voice whispers in my ear. “You need to run, Henry.”

I try to catalog what I know. I have the vague memory of writing in a leather journal. A woman with green eyes always insisted on it, even on the bad days, pushing it towards me along with a glass of orange juice. In the absence of it, I catalog aloud.

“My name is Henry,” I say. “I am old.” I reach for more and am delighted when I find it. “I was a soldier, like my father. After that, I built roads and married a beautiful woman.” At the mention of her, my eyes are drawn to the photo on the wall. “She took care of me, until she went away.”

I reach for more; there is only fog.

My stomach rumbles. The world beyond my door is a mystery, but my nose still works, and I smell bacon.

I stand on creaky legs, thankfully remembering to put my pants on before exiting into the hallway. The walls beyond, painted a chipped yellow the same shade as piss, are lined with old pine doors.

I step over a muddy bootprint outside my door and follow the scent down the hall, stopping only when I notice two men in scrubs working in a nearby room. They are collecting bedding and shoving it into a laundry cart. A trash can sits in the hall just outside the door, a receptacle for the prior occupant’s worldly possessions. On top, there is a photo—a white-haired woman with her arms wrapped tight around the chest of a little girl. The glass is cracked, a dark line splitting the woman’s face in two.

“Who was she?” I ask. The men pretend they don’t hear me. A shred of a memory rises from the fog. Victoria’s gap-toothed smile radiating up at me, her blue eyes bright.

No, I think, that can’t be right. My Victoria’s eyes are green, not blue. Yet, I cannot abandon this girl to the garbage. Someone should remember that she existed, that she loved the old woman in the photo, and that for at least one moment, she had the same smile as my Victoria.

I slide the photo from its frame, fold it, and place it in my pocket.

The rec room is large, six battered hardwood tables positioned across its width, centered on a pair of well-worn couches. On the TV, John Wayne is pointing his trusty Mare’s Leg at a couple of scoundrels, and I think I know the movie, the thrill of memory drawing me close. But, before John can waste the bad guys, someone calls my name.

“Henry! Earth to Henry!”

I turn, dumbfounded. It’s a woman, her black hair standing out amid a sea of blue and gray heads. She is wearing a bathrobe, has a narrow face, dusky eyes, and a wry smile. I suck in my gut.

A man sits next to her, hunched over a crossword puzzle, a pair of round-framed glasses

perched on the tip of his withered nose, bald head covered in dark liver spots. He holds a shaky pen above the paper but doesn’t write.

“How do you know my—” Then the revelation hits. “Berta!”

“That’s me! George, he knew me today!” she slaps the man beside her. “Come Henry, sit with us.” I join them, my memory chugging to life like an old diesel engine. She is Berta, a widow from the war. She is the youngest person here, only sixty-one, but insane.

“I got a head full of ghosts,” she told me once. The other is George, a lifelong bachelor, an

accountant, and an expert on WWII. One day, fairly recently, George and I sat in the garden while he explained to me how Joseph Goebbels had turned a nation of normal, loving people into Nazis.

I settle into the chair opposite them. “How are you today?”

Berta’s smile, all white teeth and crow’s feet, is infectious. “Still crazy. And you? Are the boots still keeping you awake?”

“Boots?” I ask, brow furrowed. “I don’t remember, what do you—”

George grumbles something, cutting me off. Berta shoots him a worried glance. “He isn’t doing too well today. Hasn’t said much.”

George is like me, I recall. Just further along into the brain rot. I crane my neck to see his puzzle. He has only written one word, four letters in a row made for eight.

HELP.

“You hungry?” Berta asks conspiratorially, grabbing my forgotten stomach’s attention. “Breakfast is already over, but I saved a couple slices of toast.”

She produces a paper plate from under the table. The toast is cold, covered with a red jelly that tastes like summer. I wolf it down, eyes watching George, ears listening to Berta as she regales us with stories about her summer spent in Venice, and the lovers whose hearts she broke there.

George continues to work on his puzzle. By the time he’s done, the light outside has turned red, and he has written the same answer for every question.

I am lying awake in bed; the clock on my nightstand reads 3:00 a.m. I draw the comforter up to my face and breathe in the scent of home, warmth, and a woman’s lingering perfume.

There is a sound out in the hallway. That’s right, I remember, that’s what woke me, those heavy boots invading my foggy dreams. I listen to them move down the hallway, passing right outside my door. Then, a moment later, they return, going the other way.

A chill sweeps over me; I can smell blood. Unconsciously my hand drifts to the edge of the mattress and reaches underneath, running my fingers along the crinkled edge of the photo I stole from the trash bin.

As a short scream echoes down the hall outside, I bury my face in the comforter and let memories of better days drown it out.

The next morning, another room is being emptied by men in scrubs. I am intent on passing right by them. I woke with a clear memory of Berta and George, and I cannot wait to tell them.

Yet, when I near the room, something stops me. I stare, watching the two men empty the former resident’s trashcan into the larger bin in the hall. Receipts, an empty pack of cigarettes, a couple of empty whiskey shooters.

“What happened to him?” I ask the young orderly as he steps outside to toss a pile of birthday cards into the bin.

The boy shrugs. “He died.”

I stare down at the cigarette pack. Marlboro, like my father used to smoke.

“How?” I ask.

The boy glances back at me, clear annoyance on his face. “Got old, I guess.”

I don’t bother to tell the boy that I, too, am old. Something in the way he looks at me tells me that he already knows.

Once his back is turned, I pick up the Marlboro pack. The lingering smell of tobacco inside tickles a memory, silver smoke curling around a dark mustache.

“What was his name?” I ask.

The kid sighs. “Beats me. Look, man, I got a lot of work to do. Head on down to the rec room. I hear they got musicals on the TV today.”

That night, I am a child, sitting atop my father’s workbench, watching him rub varnish into the side of the oak canoe we have spent all summer building. The muscles in his arms ripple as he spreads sealant on the hull, his rugged afternoon shadow making him look every bit the war hero I believe him to be. This is years before I learn that

he spent the war getting shit-faced on a patrol boat off the coast of Brazil. He impregnated a woman there. She sent him letters, dozens, first swearing her love, then begging for money, then cursing his name, and finally pleading for him to come back. I will find these letters on the day of his wake, and I will weep while others toast his name.

But at this moment, it is summer, I am a child, and my father is perfect.

“How fast will it go? Can we take it down the Mississippi?” We had just read Huck Finn in school. “Maybe not the whole Mississippi,” my father says, puffing his cigarette, silver smoke curling over his mustache. “She’ll take on the pond out back just fine.”

“Can I name her?”

He arches an eyebrow. “Naming a boat is a serious business. Give a boat a bad luck name, bad luck is all she’s going to give you. You sure you’re up for it?”

I nod, gravely.

He looks at the canoe again, then at me. “Well, then she’s all yours. What’s her name, cadet?”

I deliberate silently, head bowed until the perfect name comes to me. I open my mouth and the word breaks apart on my tongue. I try once more to say it, but only a dry hiss leaves my throat.

It’s hard to think. Someone is walking behind me now, heavy boot falls scattering my thoughts like clouds of gnats. I look to my father and his face is gone. In its place, a circular window has been cut into his head, through which white fog falls in billowing sheets.

“What’s your name, cadet?” he asks. “Gotta hold onto that.”

I wake, covered in cold sweat. The boots are in the hall again.

I go over what I know. It isn’t much.

Except for the dream. It’s my only clear memory, a lighthouse in the fog.

“Do you believe in the afterlife, Henry?” George asks me. It has been a time since the dream, days, maybe weeks. Long enough for the flowers in the yard to bloom.

We are sitting in a pair of battered chairs on the back lawn, watching Berta as she sketches the butterflies on the begonias. She works in crayon, all they’ll let her have.

I consider the question, searching my brain for anything that might tell me how I feel. “Maybe,” I say with a shrug. “I hope my wife is there.” Loreen, her name swims to mind. The name tastes like tears, and my heart twists.

“Me too,” George says. “Except the wife. Between you and me, I never saw the appeal.” He runs a leathery tongue over his thin lips. “What do you think it looks like for people like us?”

“People like us?”

George rolls his eyes and taps a finger to his wrinkled temple. “Ya know, people with the Mad Cow, the brain rot, the Forget-Me-Nows.”

“Same as everyone, I guess? Maybe we get it all back.” I try to think about what that might feel like. The few memories I have are so precious to me now, each a beacon of light radiating in the lonely dark.

“Maybe. But… what if we don’t?” His eyes are distant, his hands clasped in a white knuckled grip.

“What do you mean?”

“I mean, what is a memory if not a piece of us? And when it’s all gone, what happens? Our souls won’t know where to go? Or worse, what if we can’t go anywhere. Like, without the things we did, neither side knows where we belong. No heaven, no hell, just…”

“The fog,” I finish, thinking of the hole where my father’s face had been. We both fall silent for a moment, staring at Berta, at the butterflies, at nothing at all.

“Way I figure it,” George says glumly, “we are going to find out one way or another. And chances are we’ll both be drooling idiots by the time that happens.” He falls silent for a moment, his eyes set and hard, lips drawn back in a skeletal grimace.

Then, he slaps me on the shoulder and stands, knees cracking in protest. “Suppose all we have are the good days, and Lord knows neither of us got a lot of those on the horizon. Come on old man, I’ll whoop your ass at some checkers.”

We play most of the afternoon. Neither of us remember the rules, so we make them up as we go, working around our Swiss cheese brains. By the time Berta joins us, the board is cluttered with checkers, markers, a black pawn from a chess set, and forty-seven dollars in Monopoly money. We are both red-faced and sick with laughter.

That night, feeling more myself than I have in a long time, I pray to God that my Loreen is at peace. I pray that she is watching me as I inhale her scent from the comforter.

The boots are in the hall again.

It is close to 3:00 a.m., the only sounds are the constant hum of the air conditioner and the soft squelches of the boots’ wet rubber soles against the linoleum.

I look around the room. The same nightstand, the same clock, the same photo on the wall. Only, the couple in it is no longer smiling. Her eyes are filled with pity, his with horror.

The boots draw closer, the smell of blood announcing their arrival, a choking coppery scent that seems to fill my throat. I gag, pressing myself down into the bedding as if the ghost of Loreen’s perfume could kill the slaughterhouse stench and drive the thing away. It doesn’t. The boots come to a stop outside my door.

“What do you remember?” a voice asks and for a moment I think I recognize it. It’s a man’s voice, deep and sure. But wrong too, as if a dozen other voices whisper softly just beneath it.

I look at the door. Surely I didn’t hear that? I have a bad brain, the Mad Cow, the Forget-Me-Nows. It was some fragment of a dream, dragged into the waking world. Yet, I find my hand snaking under the lip of my mattress, touching the photo, then the cigarette pack.

It speaks again, this time louder, as if smelling my doubt. “Do you remember me?

I do not dare to respond. I lie there, frozen, eyes on the door until I hear the sound of the bootsteps retreating down the hall.

When I next emerge, a woman is at my door, a plastic gold tiara set into her wild tangle of black hair and a tray of blue frosted cupcakes in her hands.

“Good morning, Henry! And before you ask, no, we are not lovers. Good thing, too. Lovers get the door; friends get to share my birthday cupcakes.”

I smile. “I’m sorry, darling, have we met?”

“We most certainly have. And now, you’re going to spend the day worshipping me.”

Sitting at our table in the rec room, three of us eat until the frosting has dyed our lips and tongues blue, prompting the Queen’s bald friend to remark, “It looks like we just blew half of Smurf Village.”

Her laugh is like a cannon, blowing through the room, leveling all in its path. We laugh with her. She manages to convince an orderly to put on her favorite movie, an old black and white film where people dance their problems away. Halfway through, watching Fred Astaire foxtrot with a red-headed beauty under a crystal chandelier, the Queen gets swept away by the music and begins to dance herself.

She pulls the bald man to his feet despite his protests. “No! No! I couldn’t, my knees! Berta! Berta!”

“Up!” she commands. “Respect the crown and rise, serf!”

He rises, to my surprise, and seizes her around the waist. He leads her in a fast waltz around the room to the delight of other patients, creaky knees be damned. By the end, he is smiling and red-faced. He gives a flourished flip of his wrists as he bows to the crowd.

“Thank you,” he says, “thank you. Please stick around for the after-show and enjoy the buffet. I’ll be here ‘til I die.”

The Queen comes for me next, and I don’t fight her. I try to lead her, as the bald man did, but succeed only in smashing her toes with the first step.

“No worries, my dear,” she whispers, “I know the way.”

She leads me into the dance and before long the music takes us. The bald man claps his hands in rhythm with our steps, the entire room spinning around us. Then, she deposits me in a chair and takes to the tabletop.

Her skirts billow about her as she kicks and spins, the orderlies rushing to pull her down, only for her to dance away, leaping to the next table. She blows a kiss to one of the orderlies.

Each time they get near she jumps again, her eyes wild with delight.

“Do you think she is going to be lonely, when we’re gone?” The bald man asks, voice hushed.

I blink at him, placid as a cow. “I think she’ll be fine. She’s a charmer. Besides, I’m not planning to go anywhere. Are you?”

He looks at me a moment, then sighs. “Do you have any idea who I am?”

“No,” I admit, “but I think we’re friends.”

“That we are,” he says, looking back to where the Queen is balancing atop the couch, teal-scrubbed men closing in on all sides. Just before they pull her to the ground and jab a long needle into her neck, she takes a bow to raucous applause.

They drag her back to her room. Just as she leaves our sight, the bald man stands, and I smile up at him, unburdened with even the simplest of thoughts.

He stares at the hallway to the residential rooms, where the Queen has just vanished. “Do you ever hear the boots outside your door?”

“No,” I tell him, “I don’t think so.” Yet, for some reason, my stomach churns and my breath catches in my throat. I feel cold. I smell blood.

He nods, bright eyes set knowingly on me. “That’s good. Take care of her.”

George is gone. I know it before I open my eyes, the thought repeating like a pounding drum, summoning me back from the emptiness. I sit up in bed and stare at my closed door. Outside, other residents shuffle by on their way to the rec room, their slippered feet whispering on the tile.

George is gone.

How long ago was Berta’s birthday? I can’t be sure, but I think no more than a week, maybe two. George was bright that day, brighter than me. He couldn’t be gone. Most of the people who died of the Forget-Me-Nows were broken things by the end, barely able to move, let alone dance. George, by contrast, was alert, strong. Some days, it’s almost like he isn’t sick at all.

I’m just being paranoid, I reason. I stand, shave, and brush my teeth, the familiar routine easing the dread in my stomach. Then, I step out into the hall and turn, intending to walk down to the rec room like any other day.

George’s door is open, a trash bin in the hall outside.

A sharp, cold blade slides into my heart. Inside, two orderlies are stripping the room of everything that made it his.

“Where is George?” I ask.

“He died,” says one of the orderlies.

I don’t ask how. I already know the answer.

I grab one of George’s half-filled-out crossword puzzles from the trash can in the hall. Every question has the same answer.

HELP.

That night, I slide the crossword beneath my mattress to join my other meager treasures in the dark.

I spend a day with Berta in the yard, sitting on a bench near the small flower garden. It has been a time since George died, though to me, it feels like earlier that afternoon.

Berta tells me that she once seduced a prince who gave up his crown to be with her. She spent a long summer with him, hunting tigers in India before running off with the captain of a whaling ship and breaking the prince’s heart. I sit on her words with rapt attention, believing every one of them.

“Do you think George knew he was going to die?” I ask when she is done, the question loosed before I know I want to ask it.

Berta watches a butterfly, a Painted Lady, crawl over the top of a lily. She sucks in a breath, puffs out her cheeks, and lets it out slow. “He did. He said the boots were going to get him.”

“The boots?” I ask, unable to hide the quiver in my voice. I expect Berta to say George was delusional at the end of his life. I expect comfort.

Instead, her face goes pale, voice a haunted whisper. “You must have heard them. Everyone does around here, eventually.”

“Who is it?” I ask.

“More like what.”

“What is it then?”

The butterfly takes flight, rising slowly into the air above us. “I don’t know,” she whispers. “Maybe it’s death. Maybe we can hear it coming, when we’re close. Or maybe it’s a ghost; people die here all the time.” She leans back, eyes unfocused and set on the chipped wooden fencing where a horizon ought to be. “I think it’s a hungry thing, though. I can hear it salivating.”

“Hungry for what?”

“Who knows? Does it matter how it gets you? Result is the same.”

The finality in her voice twists the dagger that has been in my heart since George died, and I choke, fighting back tears. It’s real, God help me, it’s real. “It spoke to me.”

I don’t notice my hands are shaking until she takes one in hers, folding her fingers over my hand and pulling it to her chest. “What did it say?”

“It asked if I remembered it.” The memory is clear in my mind, without the faintest shred of fog. “I don’t. Or I don’t think I do. But its voice—I think I know it, but I don’t remember where from. It’s driving me crazy.”

She doesn’t reply for a long time. We sit, watching the sky turn gold then the purplish-green of a bruise. Finally, she lifts my hand to her lips and kisses me on the knuckle.

“You can stay in my bed tonight. I’ll sneak you in,” she says. “No funny business, mister. You shouldn’t be alone right now. Not with the boots after you.”

“Do you really think it’s after me?”

“Yes. But not tonight. Tonight, you’re mine.” Despite what she says, there is funny business that night. It is sweet, and gentle, and kind. I call her Loreen. She doesn’t correct me.

“I miss you,” the woman with drowned emerald eyes tells me. She is sitting beside my bed, one hand extended and folded over mine. We are alone, but we are not in the hospital. My bed sits in the middle of a clearing in the fog, its billowing walls stretching up out of sight on all sides.

“Do I know you?” I ask.

She laughs, then chokes. “Yeah, I should think you do.”

I study her for a moment. Her face is familiar but her hair is short, and unnaturally dark, dyed.

“I— I’m sorry—I don’t—”

She squeezes my hand tighter, “It’s ok, Dad. You don’t have to stress yourself, I’m right here.”

“Victoria?” I blink. “You changed your hair.”

The smile she gives me is a summer sun, its warmth penetrating every part of me. “Dad! I’m sorry, that must have confused you,” she runs a hand through her dyed locks. “I didn’t think, I—”

I give her hand a return squeeze, “No, it looks good.”

She laughs again, and then, inexplicably, begins to sob. Operating on some ancient instinct I cannot name, I pull her towards me and she curls against my side. In a flash, she is a child again, her arms stretched wide over my belly, her face pressed against my chest. In one moment, a thousand forgotten nights drift through my mind, nights spent holding my little girl as she quaked in fear of thunder or the terrors that lived in her closet.

“I wanted to see you again,” she says into my chest. “The doctors called. Said it wouldn’t be long now.”

“Long till what?”

She doesn’t respond for a long time and when she does it is in a small whisper, the kind reserved for words too painful for daylight. “I wanted to tell you that I’m sorry. When Mom died, I knew you needed help. I should have brought you home, I should have cared for you. This place, it is all I can afford but you shouldn’t have to die here.”

“Hush,” I whisper, running a hand through her hair. “There, here, all about the same to me now. It will have me soon.”

“I could take you home?” she says.

I shake my head, “Not enough left of me to take.”

“I don’t want my daddy to die.”

I point to the wedding photo that floats over the end of my bed. The man and the woman are smiling, their hands pressed flush against the woman’s belly.

She lifts her head and sniffles. “That was our beginning. All three of us.”

“Then remember them,” I say. “Remember us.”

We lie like that for an eternity, just me and my little girl in the fog. I know what is coming next, can hear it echoing across the emptiness, the sound reverberating in the icy air until it seems to surround us, enclose us.

It’s coming.

Berta is gone. Her room is bare and empty. I ask an orderly if she was moved. He tells me he doesn’t know. I have to find out from one of the nurses that she suffered an aneurism in her sleep a month ago. I sit on the bench in the garden, where she and I had once shared a long afternoon, and touch the sun-warmed stone where she sat.

I try to remember the way she smelled, but the only scent that comes to mind is blood. I weep. I am still weeping when I see the butterfly, the Painted Lady. It is dead, lying on its side in front of the bench, and I lift it as if cradling a child.

“I miss you,” I whisper.

A passing wind flutters the Lady’s dead wings.

“I’ll remember you, as long as I can.”

The boots are coming, the soft squelch of rubber on linoleum dragging me inch by inch back into myself. I make myself small, comforter drawn up over my head, eyes peeking out of a thin slit to stare at the door.

The smell is worse this time, rotten, like offal left under a summer sun. Then, to my horror, they stop at my door.

“Do you remember me?” it asks from the other side.

“No,” I blurt out, heart slamming in my chest. “No, go away!”

The thing in the boots doesn’t reply, but already I can hear something else, the soft click of metal sliding against metal. The brass handle begins to turn. I bolt to my feet and press my back to the wall. My mind races, thoughts melting together into a panicked, animal scream.

I need a weapon and, as if drawn by some strange gravity, I find myself reaching for my mattress. I grab the edge of it and flip it up. The photo of the little girl is there and the empty pack of Marlboros, but that isn’t all. An empty tube of lipstick, a crusted band aid, a peach pit, and more. Where had it all come from? And more importantly, how the hell can it help me? I push the trash aside, hoping for a knife, or a rock, but there is nothing. My hand falls to the photo of the little girl, my little girl. I grab the photo and remember the way Victoria pressed against me, and the atom bomb radiance of her smile.

Maybe we can feed it?

Berta’s words flash across my mind. Feed it? Feed it what? I have nothing but these trinkets, these—

“Memories,” I whisper, my voice cracking, eyes wide on the photo in my hand. I think to grab a different one, anything other than my Victoria, but the brass handle has almost turned enough to open. I hurl myself against the door in panic, and the thing on the other side pushes back with a terrible, inexorable, strength.

“Give it,” the thing on the other side of the door moans.

My legs are already burning, my neck painfully taut. I’m not strong enough, I realize with a growing dread. The rest of the treasures are safely tucked across the room from me, though they might as well have been on the moon, for all the good they could do me now. I stare at the photo crumbled in my hand and begin to sob.

“I’m sorry,” I choke. “Please, forgive me.” Then, shoulder still braced against it, I slide the photo under the door, my fingers tracing the little girl’s face right up until it vanishes from sight.

The shaking stops and I hold my breath.

I hear the crinkle as the photo is lifted off the ground. All falls quiet—too quiet. I strain to hear.

“Good enough,” the voice eventually says. A memory comes to me, so clear and sharp it seems to be happening right now.

“To the moon!” Victoria demands. It is a sunlit day, and I am young and whole. I take her in my arms and thrust her toward the sky, making rocket ship noises with my lips.

“Mission control, this is Houston. We have a problem!” I dive her headfirst toward the ground, stopping her fall at the last second and carrying her at a jog, her face hovering inches above the grass, her arms spread wide.

“Faster!” she screams. “We gotta reach the moon!”

I release her and she glides forward on the wind, before breaking apart into fog, one bit at a time.

It is almost dawn before I manage to remember how to stand and open the door.

The photo is gone.

“Who are you?” I ask the stranger.

She squeezes my hand and says a name, but the sound comes out like a dry wind.

“Do I know you?”

Her tears are hot when they drop from her face onto my palm. “I wanted to stay in town, till it was over.”

“Till what was over?” I ask. “Am I going home?”

I give it the lipstick tube the next night, the memory of a girl I loved and lost in college. Then the night after that, the peach pit goes and along with it a soldier I fought beside in another life.

As my last thought of him fades, I can almost see him standing in the room with me, dressed in combat fatigues, a foggy hole where his face should be.

“What’s the exit plan here, Hoss? You don’t got a lot of ammo to spare.”

I give it the crusted band aid, a pink sock, a shiny pebble, one step at a time, marching dutifully towards perdition. As I give it the pebble it speaks again, voice so familiar but so wrong, alien.

“These memories are weak,” it says. “I know you got something better. Feed me, Henry.”

I feel thinned out, my thoughts growing wispy and ephemeral. My body aches down to the bones, and my eyes feel like lead balls sinking into my skull. It isn’t leaving. Must still be hungry. So, I go back to my hoard, snatch up the empty Marlboro pack and begin to shove it under the door.

Then, with a violent tug, the pack is pulled the rest of the way through to the other side. There is a dismissive snort, and a chuckle that sounds as alien as it is hauntingly familiar, distorted and wet. I imagine a throat filled with blood, spilling endlessly out of a twisted mouth.

“Do you think this will satisfy me forever?” it asks.

“Will it satisfy you tonight?”

“You know what I want.”

“Just go away, please. Don’t take them too.”

It does not respond. As its heavy footsteps fade, I remember my father, sitting tall in a canoe as he glides silently down the river into a bank of icy fog.

I stare down at the space beneath my mattress, crippled with an impossible decision. Only the crossword puzzle and the dead butterfly remain.

The boots come slow tonight, one methodical step after another.

“I’m sorry,” I whisper, hands hovering over the two objects before finally lifting George’s crossword. I read his final words one last time, trying to hold his reddened, laughing face in my mind.

Then, with a stone in my stomach, I slide it under the door. Yet I can’t let go of it, my fingers pinched on the corner. The boots come to a stop and yank at the puzzle.

“No,” I plead, tears in my eyes. If it takes the paper, George will be gone; nobody else is left here to remember him. I try to pull the puzzle back, but it’s too strong, ripping it from my hands.

It laughs, not with one voice but hundreds, thousands, so loud it hurts. I scream and weep, begging it to go away or to just kill me.

It leaves, eventually, but not before speaking in George’s voice.

“Help me, Henry,” it says. “For the love of God, help me.”

George dances in my head. He takes a bow and becomes fog.

In the morning, I ask for a sheet of paper and a pen from one of the staff. Sitting alone in my room, using the nightstand as a table, I write a letter to Loreen.

I tell her I miss her, and that I can’t wait to see her when I get back from the war. I tell her that I think we should finally have children, and that a couple as good looking as us have a civic responsibility to procreate. I tell her that I think I could be a good father, if given the chance.

Then I remember that she is dead, and my tears make a black smudge of my signature.

I blink and I am sitting in front of my door, cradling the dried-out corpse of a butterfly. I hold its gossamer wings apart, pinched delicately in calloused fingertips.

I almost drop it in surprise, looking around my darkened room, eyes wide. How did I get here? I was just thinking of—of who?

“Do you remember me?” the thing asks from beyond the door, and my heart freezes in my chest. That’s right, that’s why I’m sitting here, holding my only friend.

“Please,” I whisper, “not her. Please.”

“You have to remember me,” it says.

“I don’t!”

The door shakes in its frame. “You have to!” it shouts, its shout twisting into an inhuman metallic whine. “You have to remember me, Henry!”

I scream and shove the butterfly’s corpse beneath the door.

“I’m sorry! I’m so sorry Berta!”

The door shakes, the thing echoing back my scream in my own voice. I scramble under the bed, dragging the comforter with me and screeching like an animal, my entire body rigid, my muscles cramped in terror. I scream and scream, until two orderlies burst in and drag me into the light.

They press something sharp into my arm. A warm darkness envelops me.

Berta walks into a foggy jungle and vanishes.

When I wake, I know I have always been alone here.

“How are you feeling today?” The doctor in the cat-eye glasses asks me.

I moan in terror.

“Non-verbal,” she says, scratching on her notepad. “Are you in any pain?”

My words are but a groan.

“Just try to relax,” she says, already standing to move along to the next room. “It won’t be long now.”

I take the photo off the wall and hold it up to the thin light from the yard.

I wonder if this is how those faceless others felt, before the end. I wonder if they found peace in the afterlife, or if they became hungry things.

The boots are in the hall, walking at a leisurely pace, a victor’s march.

The man in the photo is a stranger to me. I trace his narrow jaw and bushy eyebrows with my fingers. Distantly, I think I remember the feeling of holding my wife close as we danced at our wedding. Did we make love that night? Was I a good man? Does it even matter anymore?

The boots come to a stop outside my door and I brace myself.

“Do you remember me?” it asks.

I look at the photo, then at the door, and for the first time I realize I do know that voice, have heard it before, but never like this, never outside my own head.

The door swings open.

A figure stands in the shadows, with a clean jawline and dark, piercing eyes. It is dressed in a tuxedo, standing tall and strong. Where its face should be there is a hole, from which fog falls in freezing sheets. I look to the photo, the man is smiling wickedly up at me, the woman dead in his arms.

“You know who I am?” And I do. I see it all, reflected in this thing with my voice. I see myself holding my wife’s hand as cancer devours her, I see the love in my daughter’s eyes, I hear guns firing, a jackhammer screaming, the sound of George’s knees creaking as he and Berta dance, all the moments that make a life. Every bit of me, stolen and glued back together until this thing is more me than I am. All but one piece, all I have left. I feel something tug inside my head, a thread pulled taut.

“Henry,” I whisper.

I press my face into the comforter and breathe deep Loreen’s perfume, basking in my last mote of light. The thing steps forward. George’s face appears in the window in its head, leering maliciously down at me. Then Berta’s, and Loreen’s, and a dozen more, a slideshow of familiar strangers that ends exactly where I know it will. With a man’s face, my face.

“I’m so hungry.”

The thread snaps.

My name is Henry. I am old. I was a soldier. After that I built roads and married a beautiful woman.

My name is Henry. I am old. I was a soldier. I was a road. I married a beautiful woman.

My name is Henry. I am. I was.

My name is Henry.

My name is—