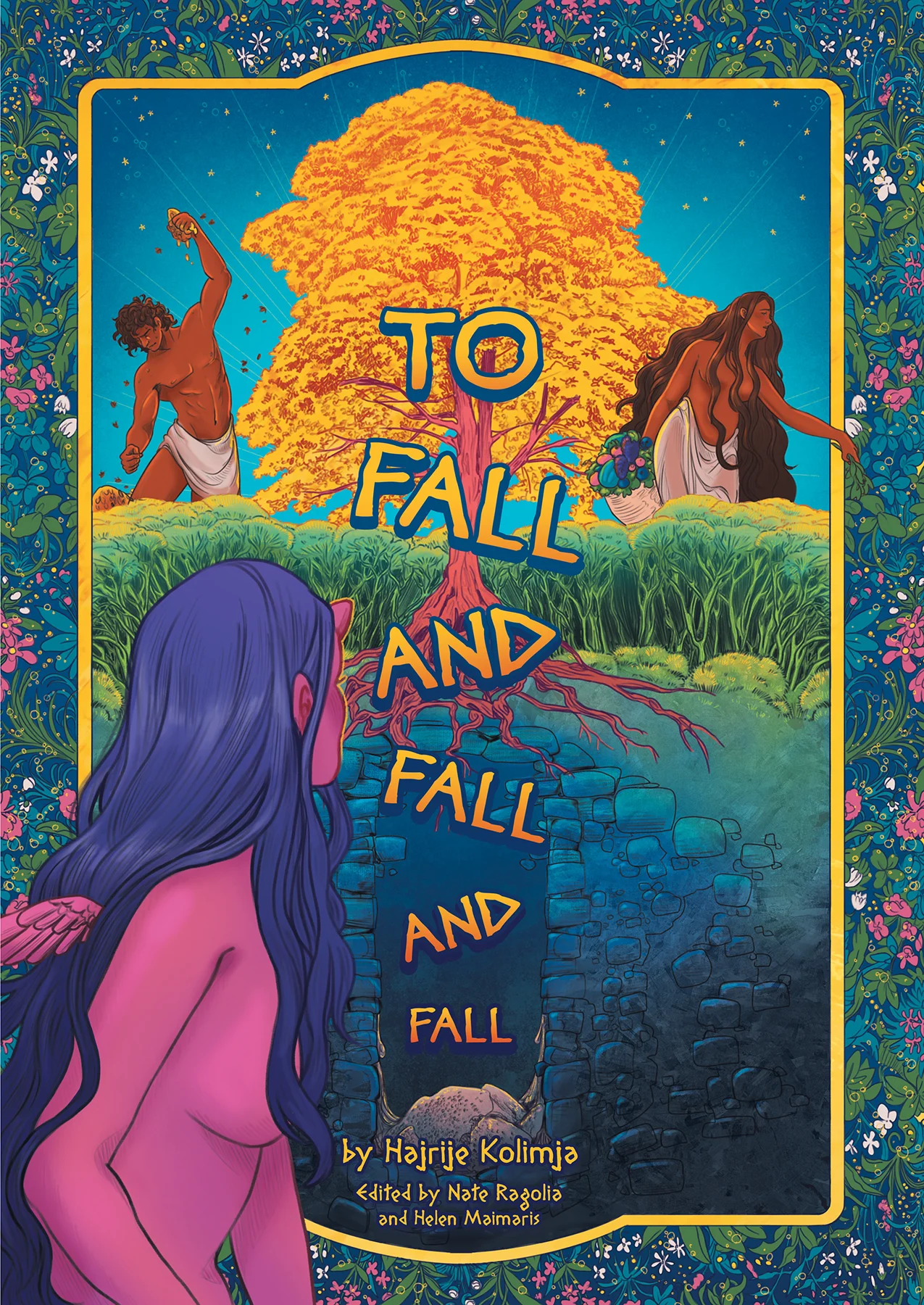

Iblisa was a native of Jannah. That was where she lived. In its center was an Old World Sycamore and a Well made of stones, wet with a coppery sheen. Scattered in perfect disarray were trees of olives, apples, lemons, oranges. Grapevines and tomatovines. Anything branched or stemmed, all meaty in their ripeness. Her djinn friends lived in these boughs, their black figures chattering amongst birdnests and beehives.

Of all the creatures the Voice had created, Iblisa was the closest to perfection. While the Voice imbued both Iblisa and the djinn with spirit, it was only Iblisa that the Voice also gave a heart. Though she could not see it, she could feel it—red and beating and full. Thump, thump, it went.Thump, thump.

“I am endlessly indebted to you,” Iblisa had told the Voice after her creation, her face turned up to the jagged clouds.

“And I will soon be indebted to you,” the Voice replied, echoing from above and beyond. “With your constitution comes privilege and responsibility. You must care for this place and its inhabitants. All you require is the water of the Well and the fruit of the trees. Just be sure to always nourish and protect the Old World Sycamore, for the water in its roots is the blood in your veins.”

This explanation confused Iblisa, so she inquired after its meaning.

“That is why you are distinct from other entities,” said the Voice. “I could gift you a heart only because your life was connected to another.”

Iblisa studied the tree, its pulsing leaves. It filled her with a special, intoxicating fear. How beautiful it was to have such a precarious bond, she thought. It was a blessing to be a keeper. To be chosen to keep. To be chosen at all.

Perched on the Sycamore branches were the djinn, little black shrouds. Though they had no eyes, Iblisa could tell by their stillness that they watched her with reverence. Their susurrus, though unintelligible, was a quiet, prayerful song.

Iblisa began each day by gathering the bucket from the Well, first drinking and then pouring its contents at the base of the Old World Sycamore. The water would chill her tongue and pulse under her ribs.

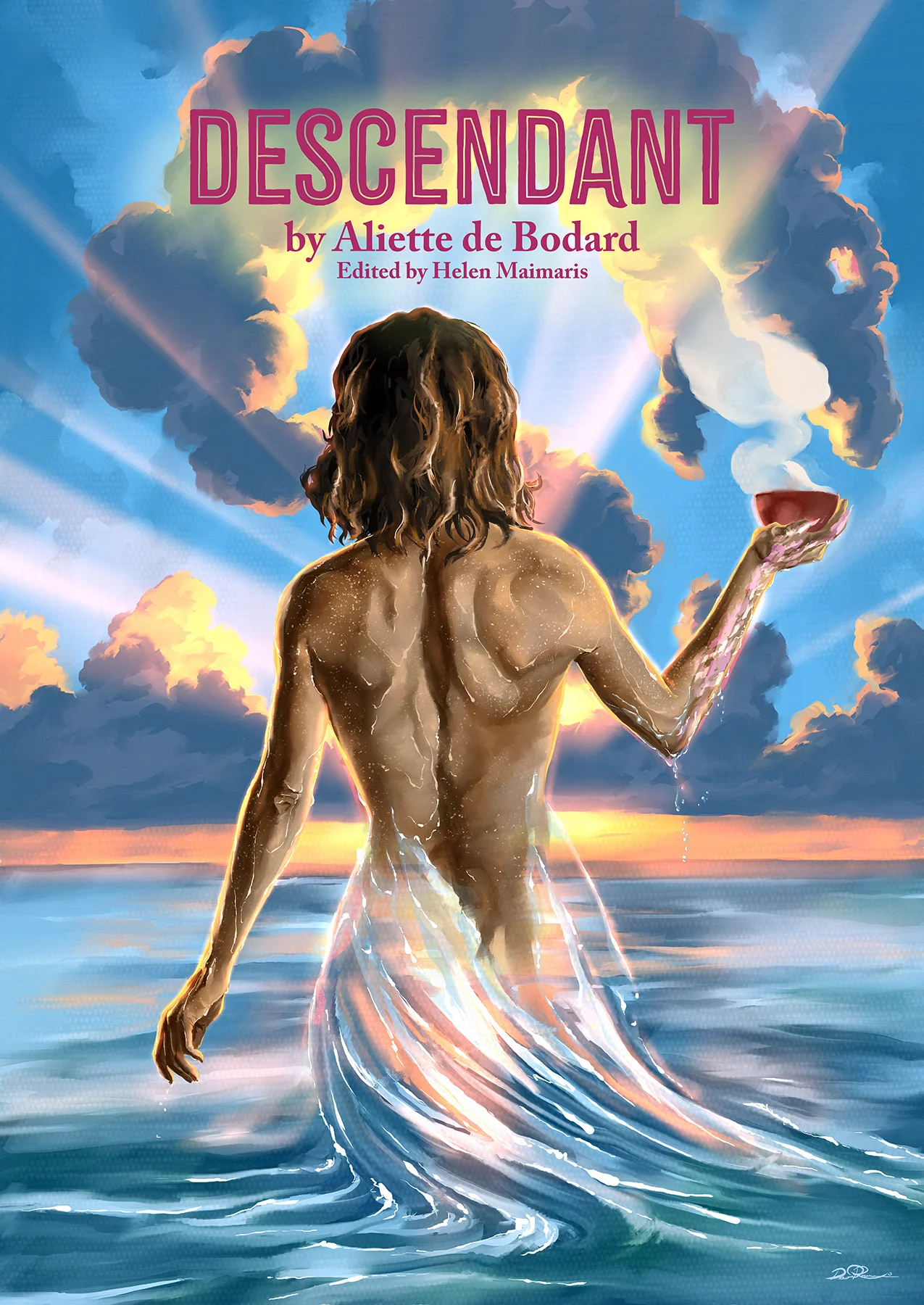

This rhythm was disturbed when two creatures appeared as if dropped from the crown of the tallest tree. Unlike her, they possessed neither stubby horns nor small flightless wings; instead, they had hair—the woman with brown waves and the man with black curls. Unlike her, neither had pink, fleshy skin; instead, they were a beautiful almond-brown, with some creases and tiny bumps on their faces. But like her, they had eyes, though theirs were not yellow but hazel. They had smiles with teeth. They had ears and chins and necks. Arms and legs. Most importantly, they had speech.

“Hello, I am Eve,” said one.

“Hello, I am Adam,” said the other.

“Bow down,” boomed the Voice from above. Iblisa knelt on the slick grass. The djinn amassed beside her, expanding and contracting. “Please care for my most recent creations as a good host would.”

Iblisa welcomed the two and led them through the endless garden. The leaves on the trees sparkled with dew and could be mistaken for stars were it not for the ground below. Iblisa listened to their steps—the confidence with which both Eve and Adam walked. It warmed her to know that she could make them so comfortable as to move in such bold ways. They wove around the thin and thick trunks, under high and low branches, alongside bees and butterflies. She led them to soft straw hayplaces where they would sleep. Eve and Adam smiled in what was perhaps gratitude—but then abruptly frowned.

“I am hungry,” said Eve.

“Me also,” said Adam.

“I will show you,” said Iblisa.

Her voice was firm—ready to share her world and see how it could grow . She turned to the Old World Sycamore. The gold in its leaves oscillated like blood in a fragile vein. The djinn watched breathlessly.

Over three days and three nights, she taught them how to work the land; to pick and soak olives; to save grape seeds and select the soil for planting; to wash an apple in the cold, cold creek and eat it after. On the fourth morning, sitting under the Old World Sycamore, Iblisa explained: “You can work almost everything here, excluding that which is divine.” She pointed at the leaves above, their gilt Arabic script akin to pulsing flames. Eve and Adam looked up at the tree and nodded.

However, later that day, Iblisa felt a stabbing rip from her navel to her breastbone. A phantom wound. She looked toward the Sycamore, and that was where she saw him: Adam holding a leaf; its gold turning gray; his eyes marbling with disinterest; his hand releasing what it had plucked.

“Stop!” Iblisa yelled. “You cannot touch this tree. Have I not clearly explained?”

“My apologies,” Adam said. “I hadn’t realized the gold would fade.” He kicked the leaf and walked away.

Iblisa watched him that afternoon as they sat around a large tree stump, eating. Poor Eve! Adam took the food from her hands. He ate Eve’s pears, grapes, and apple, too. Eve tremored with impatience, her face purpling. Iblisa was shocked into silence; it disgusted her to dine with someone who held others in no regard.

“I picked those by myself, for myself,” Eve said.

Adam shrugged. “I apologize.” There was no shame in his voice.

Iblisa went and picked more fruit, bringing back pears and grapes and an apple—setting them on the stump before Eve. Their skins were dewy and they impressed wet traces onto the wood. Splotches of imperfect circles. Eve ate in the order each fruit was given. Iblisa enjoyed watching her, but not directly, for she did not want to cause discomfort. Just a glance every so often. She loved hearing the crunch of the pear- bite, the pop of the red grape. She loved seeing the juices of the apple dripping onto the rough wood. Nothing was more endearing, Iblisa thought, than a messy eater. Someone who eats with their heart and not with their stomach.

Adam rose, his legs imprinted by zigzagging blades of grass. He threw his seeds onto the ground, disfiguring it with his carelessness.

“There is a proper place for those,” Iblisa said.

“Won’t they grow the same wherever they are?”

“It is irresponsible to grow something without considering where you’ve planted it. You can’t give a thing life just to let it die. There is no room here for the tree to grow. Can you see the roots under this stump?” They looked down at the protrusions, which resembled veiny and curved legs that might pick up and travel far away.

Kneeling, he collected seeds one by one until he groaned and said, “I cannot find them all.” He held out his palm with enough seeds for only one pear, a few grapes, and half an apple. The rest were lost in the verdant mess. His line of sight moved beside Iblisa—to the hand she had not realized she raised, cupped and ready to swing. She lowered it, slowly. Adam walked away, as if unaware of what Iblisa’s impulse could become. The independence of her body startled her, but she found herself more affected by Adam’s unaffectedness.

Eve leapt up and took Iblisa’s hand into hers. “Forgive yourself,” she said. Eve’s palms were full of such warmth that Iblisa felt ashamed to be the subject of her care. She felt undeserving, worried about the bounds of her power.

The djinn warbled low and long. Iblisa had never heard such a sound. When she looked their way, they shrunk back, as if afraid of her gaze. Iblisa’s heart ached like something uglier than itself.

Thump. Thump. Thump.

Night came and the stars curled into new constellations. The djinn formed opaque masses on the branches of the trees—obscuring whatever fruit lay behind them. Butterflies blended into leaves; bees crawled along scaly trunks. Eve and Adam went off to slumber. Iblisa slipped into a faraway corner of the garden to speak with the Voice.

“I greatly admire your work,” Iblisa began.

The Voice thanked her, Their tenor pounding in her ribcage.

“But, respectfully, I think this last one is defective. Not Eve. The other one.”

“Adam? Defective? However do you mean?”

“He provokes and disrespects others. Worse yet, he seems unmoved by the distress he causes.”

“He has faults,” the Voice answered. “But he will learn. What else can we ask of him? After all, he is a person.”

“What is a person, exactly?”

“A being who hopes and fears,” said the Voice. Just like herself, Iblisa thought.

The Voice spoke again. “Give him time. Adam needs time.”

“But I fear the emotions he draws from me,” Iblisa said. “I shudder at the creature he could make me become.”

“He cannot make you anything. You are your own becoming.”

Her throat went thin. The stars blurred into each other.

“You, too, need time,” the Voice added. “After all, a raised hand is a threat. Learn to comport yourself, as you mustn’t harm Adam. It would be a disservice to your being.”

The conversation left Iblisa dissatisfied, and her fear transformed into bitterness. Jannah was full of time, and she believed she used it to the best of her abilities. But how much more of it would Adam require? From where would it come? And from whom? She returned to her hayplace, thinking of the uselessness of her heart if it could not translate itself into words—misunderstood by her own creator. The tree trunks now appeared scabby and dry. Unattended wounds.

A few more days passed in relative peace as the trio took to their chores. They watered the trees, disposed of rotten fruit, rehoused fallen bird nests, picked tomatoes off vines for midday meals, snapped pomegranates from their stems—splitting them open and beating the arils into their palms.

“The work of care is not easy, but it is rewarding,” Iblisa said one morning, studying Eve’s fingers under the shade of a plum tree. The laboring had stained them scarlet, olive, and umber. Above, bees buzzed, flying to and from a hive scaffolded along the trunk. The slender tree drooped with the weight of the honeybee home. How brilliant was the miracle of life, Iblisa thought. How random its choices and, still, how flourishing.

“Rewarding how?” asked Adam.

“We will be gifted sweet surprises,” said Iblisa. “Such as this.” She pointed at a piece of beehive at Eve’s feet. She tore the honeycomb into three parts, handing one to Eve and the other to Adam. The honey oozed. They knew, intrinsically, how to eat, drink, and enjoy it.

“Immaculate!” Adam marveled. “The bees made this?” His eyes watered pink, seemingly in awe. Iblisa nodded, surprised by his appreciation.

“And what are your thoughts?” Adam asked Eve.

“It’s delightful,” she said. Her tongue cleaned her honeyed lips.

Adam took a bucket of water and gave it to her. Eve drank zealously, and when she finished, he gestured toward Iblisa.

“I have no need,” she said. “But thank you.”

He smiled and bowed his head.

It was unusual to hear laudatory words from Adam and his interest in the opinions of others. It was even stranger to witness such displays of hospitality. What if the Voice was right? What if this man was full of hopes and fears? Was capable of being something more than himself? The bees buzzed and buzzed. Iblisa welcomed being wrong, for she could relinquish the burden of being right. There could be a future for Adam. For Eve. For herself.

At dawn, Iblisa did not awaken to the usual sunlight. It took several blurry blinks to realize the djinn were looming over her. They stood on the ground, not bobbing in the trees. Their forms had grown terrible and bipedal—forms like humans, forms of shadows. Iblisa still could not understand their whispering, but she did not need to, for they extended their opaque hands and lifted her by the arms. They pulled her along, her skin hot with unease.

They wove around the thin and thick trunks, under high and low branches, and stopped at the plum tree where the hive was now broken, its innards exposed and dripping. Jagged bits of comb weighed on the grass below. The djinn guided Iblisa along a matted honey trail, gliding quickly and quicker until they reached the Well. They crammed around the structure, their long black fingers spilling over the Well’s lip. A djinni pointed at a bucket nearby. Iblisa retrieved it and assumed her position, peering down into the Well’s magnetic obscurity. She imagined throwing herself into its abyss, how long it would take to fall. The djinn clutched her arms and pushed the bucket forward, latching it onto the hook. Iblisa let the rope rush and burn the meat of her hands. There was a splat. As she pulled it up, she noted the abnormality of its weight. The alarming imbalance.

She hugged the bucket and scrutinized what she had dredged. Chunks of hive were sharp at the water’s surface. Some bees still squirmed adrift, legs and wings propelling them in spirals. Others floated like pits of cherries. Iblisa scooped the living few, but they could not drag themselves along her skin. The little lives stopped their efforts. Each one a carcass.

The djinn exhaled as one massive black lung. Iblisa remained frozen. Held the dead bees in her open palm. How was such horror possible in a place so serene? In her home? Her bones hardened. One djinni took the creatures from her hand and walked them to the base of the Old World Sycamore. Upon its return, the shadowy figure pried the bucket from Iblisa and poured the remaining contents at the roots, too. The djinn took turns gathering the deceased from the Well until the water ran clear. They put a clean bucketful to Iblisa’s lips and she drank slowly. The chill restored her senses but not her heart.

“How did this happen?” she asked.

The djinn ushered Iblisa back to the site of the transgression. While their mouths could not speak, their bodies could. Several shifted into myriad shapes: one into Adam, another into Eve. A third figure contorted into a hive. Grumbling came from their stomachs, and Adam-djinni took a rock from the ground, using it to beat the hive. Eve-djinni grabbed another and joined his feral toiling. A chunk of comb came off into Adam-djinni’s hand, but the rest of the hive collapsed to the ground.

The hive-djinn split into a swarm of bees. They buzzed, every one diminutive and unforgiving. They swarmed Adam-djinni, who held onto his honeycomb and fitfully swung at them. He sped through the trees, the bees hounding him. Eve-djinni watched, trembling. She picked herself up, turned her attention to the fallen hive, and began dragging it along the grass.

Iblisa followed.

Then it happened: Eve-djinni stopped at the Well and heaved the hive-djinn into the structure’s depths.

There was a splash.

Before Iblisa could process her shock, the djinn returned to their humanoid silhouettes. Their eyeless, mouthless, and faceless bodies stared. Had they no sense of responsibility for the world of which they were a part? How had it become her encumbrance alone to care for this land while others neglected it, abused it?

“Why didn’t you do something?” she asked. They stood unwavering.

“You should have done something!” she yelled. Buzzing rattled her insides. The djinn shrunk into inchoate masses, slinking up and away to the boughs. They were far now. Out of reach.

Iblisa ran and ran. The wind grazed her skin, whistled deep in her ears. Clouds ripped through the gray sky, for the land was in mourning. Tears pearled down Iblisa’s face in funereal procession. The Voice said Adam needed time but mentioned nothing of Eve. What more damage could be done under the guise of patience? The djinn’s reenactment replayed in the worst parts of her mind. The heave. The hive. A haven, gone.

When Iblisa reached the hayplace, she found Adam lying with his head on Eve’s lap. He moaned, his face and neck and hands swollen into gnarls. He was red and shiny. It reminded Iblisa of her own skin, and she resented that they could be alike. Eve soaked her arms in buckets of water. Her skin was rosier. Mounds and bumps blemished her shoulders.

Iblisa had intended to reprimand the pair, but the sight of them filled her with self-reproach. It was her fault, she thought, for not advising them to be cautious around the bees, else they might do the creatures harm—or be harmed. But how was she to know such danger if she had never been stung? Could one be warned of what has not yet been discovered?

Nonetheless, Adam provoked the bees while Eve helped kill them, and in the most horrific way. “Why?” Iblisa asked. Her choler emerged as a whisper.

“We wanted more,” Eve said. “But there were too many of them, and you weren’t near to help when our modest desires turned awry.” She groaned and took an arm out of the bucket. Her fingers were pruned.

“But why discard them? Drown them?”

“I was scared,” Eve said. “Of the bees. Of what such a scene would do to you. What that would mean for us.”

A being who hopes and fears.

How awful it was to act out of panic, Iblisa thought, and shape the world with its recklessness. She begrudged Eve for blaming her, as if the abominable killing were Iblisa’s doing. But what was the nature of Eve’s fright? Was it selfless? Iblisa was concerned that it was not the same emotion as her own. It gave her the sensation of being an unfinished creation.

And yet, Eve was right in some way. Iblisa hadn’t been near to prevent the matter. To fix it. To help those who knew no better. The ugliness in her heart turned inward. It felt as if a small beast had manifested in its chambers. It fed on the organ. On the muscle. On her flesh. On her.

Thump, thump, thump.

When she stepped toward them, she noticed flecks where the skin was raised. The bees had left parts of themselves in these people. Divine justice.

“Promise me you will do no harm,” Iblisa said.

Eve winced in pain and put her arm back into the bucket. “I promise,” she said, nearly inaudible. Iblisa knelt beside Eve and studied the stingers. She pinched one and plucked it, like picking a cherry from a tree, over and over until they were all removed. Her vision bleared from the strain, her shoulders tensed. Even so, she then tended to Adam. Iblisa felt herself to be inadequate, that there were stingers still lodged in parts unknown. Never to be found, always to be endured.

The day Eve fully recovered, Iblisa found her waiting at the Well, buckets in hand, ready to water the trees together. Part of her face hid under her hair. The brown waves were tangled into small nests. She smiled without her teeth. Iblisa smiled, too, her cheeks quivering; it pleased her to see this person ready to right wrongs and care for the world she loved. The world she grew. Iblisa would trust what Eve had promised.

Wordlessly, Iblisa took a bucket, set it on the hook, and lowered it into the Well. She pulled up the thick, braided rope and gave the overflowing object to Eve. As she readied the next one, a stabbing pounded from her guts to her lungs. She coiled and dropped to her side. Eve tugged her into standing. In her periphery, Iblisa espied Adam under the Old World Sycamore. Plucking its leaves.

Iblisa’s rage churned, her body volcanic. The garden morphed in hue. The greens turned to reds, the reds to purples, the purples to blues, the blues to yellows, and all the colors in between.

“You!” Iblisa clawed his arm. “What use are your ears if you do not listen? Be grateful the Voice gave you such capacities! Use them!”

“To what was there to listen?” Adam asked, pulling away.

“I told you not to touch the leaves of this tree! To stop! I showed you the life in the garden. Its abundance! Yet you touch the untouchable.”

“How can it be untouchable if it is here, and I am touching it?”

“Being able to touch and having the permission to touch are far from the same.”

“I can make them the same,” Adam said.

“If you do, then that is theft. You are robbing it of its peace and me of my calm.”

“The tree does not belong to you,” Adam said.

The djinn came out to listen, bobbing and chittering; their presence reminded Iblisa of her inability to show bodily and vocal restraint. She threw her hands and sunk her fingers into Adam’s shoulders.

“Oh, but it does. It is my lifeblood! But it needn’t belong to either of us to constitute theft. Stealing does not mean taking from another. It means taking what is not yours! You stole the beauty I cultivated. Therefore, you are a thief.”

“I took a leaf! Are you not stealing by taking lemons, pears, and apples?” He held up a barbed finger.

“That work helps the tree stay strong and bear more fruit. It keeps me, the caretaker, healthy. This Sycamore you are touching, though, binds me to Jannah. To this life. The Voice has made me so.”

Eve stepped forward and spoke: “Adam, you cannot impose yourself on others. Look at the land. Let us respect it.” Eve motioned to the lush plenitude behind her.

“That is precisely why I must have what belongs to this tree,” he said. “Because this is not like those.”

“Leave it alone,” Eve said. Her newfound voice surprised Iblisa, how it urgently conveyed itself. It was heartening to have someone defend her in this way. A creature in whom she might finally confide and trust. Was there a name for such a being?

Adam stood there, his fists bony and imperfect. “I am perplexed,” he said. He opened his mouth again, ready to say more, then closed it. He strode in the direction of the orange and lemon trees, far enough to become small, smaller, and disappear.

The bucket shook in Iblisa’s hands, and she dipped it back into the Well in silence. Once she had filled several, she motioned for Eve to carry one in each hand to a patch of lemon trees. Eve rubbed her hands before taking one and tossing water onto the plants.

“I am sorry for his disrespect,” said Eve. “You have been so hospitable, even through our lapses.”

“I don’t accept the apology,” Iblisa said. “You need not be responsible for his puerility. It is unjust. You need only to realize your past wrongs. To be better, both for me and for yourself.”

Eve sighed and grimaced. “I hope we will all come to understand one another.”

A curious admission. Until now, Iblisa had only accounted for her own sentiments toward individual humans, not their relationships. “Are there ways in which you don’t understand him? What is your opinion?”

“Of Adam?” Eve poured the last of the water. “I do not know the right word. To say I feel revulsion is too strong. Disgust is too weak. I suppose it is my own fault.” She dropped the bucket.

“What is your fault?” Iblisa asked. Her skin pimpled with distress.

“Adam has been rough with me.” She picked a lemon off the tree, punctured its skin with her thumb, and began to peel. “Yesterday, he threw his body against mine, so febrile his skin turned green. I did not know what to do. I was given speech, but my voice is feeble. I wish I could have yelled as Adam often does when you are not around. I could have scared him into leaving me be. But his hands searched me until they stopped at my most private places. That part of me stings worse than the bees we suffered.”

Iblisa’s chest prickled and her heart slowed. To imagine Eve’s story was unbearable. She watched Eve rip the lemon and offer her half. Its flesh shone wet and bright as jewels.

They ate, and juice seeped into the splintered skin of Iblisa’s palm. She licked the tiny, stinging wounds. Her lips curled with the tartness.

“I can teach you to better use your voice,” Iblisa said, savoring the pulp and bitter skin. “That way, should Adam harm you again, you can scare him while I arrive at your aid.”

“You are magnificent,” Eve said. “Why create me when there is so much power in you?”

“Do not undermine your kind when the future may enable change. Be grateful we are here together. And look at everything we get to tend.” Iblisa opened her arms to their surroundings. The trees, the lemons, the grass, the water, the butterflies, the sky, the sun. “Let us protect it.”

And so Iblisa and Eve went back to the Well and watered more trees before resting on plush grass. Young birds continued to chirrup. The djinn murmured. “The most important thing to mind when yelling or screaming is not your voice, but your breath. The sound comes from the throat, but its force rises from the belly. Learn to breathe out your cries. Watch.”

Iblisa stood, took in a deep breath, and let out a yell that shook the grass and hushed the birds. The djinn peeked from the branches and watched, humming. She worried that she would see Eve’s face agape, full of fear. Instead, she was smiling. With her teeth! Eve rose, took a deep breath, and screamed. It resounded beyond their paradise, to places they would never know. Her face reddened and she laughed.

Iblisa laughed too. “Again!”

Eve grabbed Iblisa’s hands and screamed and screamed. Her voice wisped the clouds into impossible shapes. Iblisa screamed with her, the wind carrying their sounds so far that Adam came running, seemingly frazzled. His eyes were puffy, chest scarred from the bee stings.

“What is wrong?” he asked.

Iblisa and Eve laughed again. Iblisa had never experienced such joy—the way breath could intoxicate.

“What is wrong!”

Eve answered with a scream, and Adam brought his hands to his ears, closed his eyes, and wrinkled his face. He marched away. This time, they did not watch him become small. Instead, they listened to the birds. A pair of starlings flew up and up, toward a cloud that stretched itself to hug another.

She was grateful to feel the beauty of her heart, to be rid of its ugliness. Eve had gifted that to her in this moment—this sense of knowing herself. Who was her true creator, Iblisa began to wonder. The Voice or the woman before her?

From the ground, Iblisa grabbed another lemon. “And if I am unable to hear or help, it is important you know to use your hands.” She placed the fruit in Eve’s palm. “Squeeze until juice drips.”

Eve strained to crush the lemon, her cheeks reddening with exertion. Over and over she pressed its sides. Nothing excreted. Iblisa enveloped Eve’s hand in hers. “It is not so much about destroying the fruit as it is discovering your strength. It is good to know what you can and cannot do. The ways you are strong or weak. All you need is an awareness of your muscles, in something even as small as a finger. This will help you believe you can fight, should the time come.”

Eve’s eyes flittered. “I hope the time never comes.”

Iblisa took the lemon back, pressed the rind until it burst. The liquid spurted and dripped. It was difficult to tell whether it was her own strength or Eve’s that caused the rupture. Regardless, she delighted in accomplishing the feat together. How fragile were the makings of this world, she thought. How fragile were the beings who kept them.

That night, Iblisa prepared for bed, content in knowing she had given Eve a gift. She slept soundly, surrounded by the chirping of crickets and the singing of cicadas. In the morning, however, she awoke in a circle of djinn who were again in human-like forms.

Something was amiss.

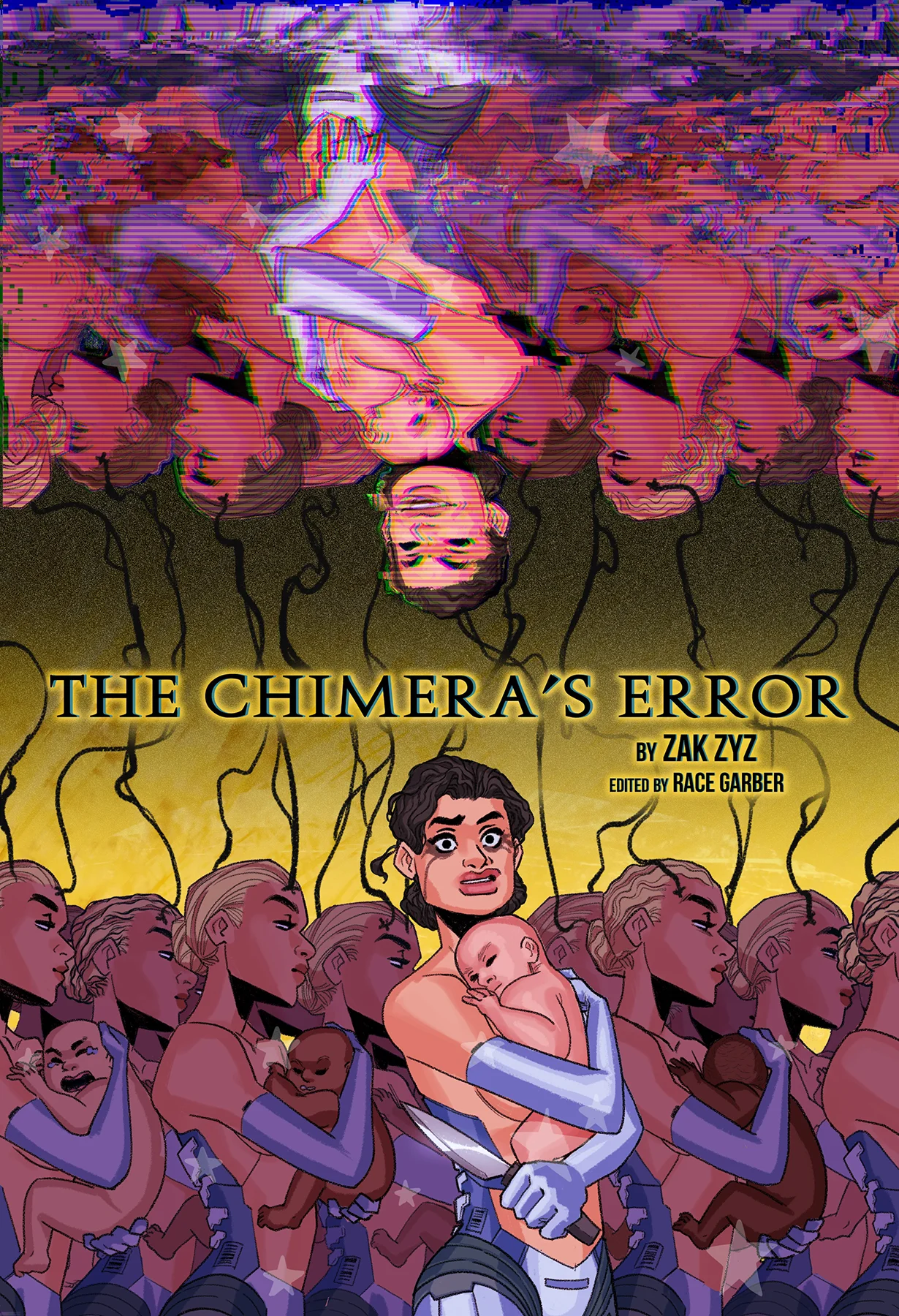

“What is it this time?” she asked, rising. Several djinn aligned. Two transformed into needled hayplaces, then another two fashioned into familiar figures: one the silhouette of Eve, the other of Adam. They were sleeping peacefully until Adam-djinni awoke. He threw himself onto Eve-djinni, and the struggle began.

The shadows transmogrified into horrible shooting shapes. Eve-djinni’s face reached up like a flame for oxygen. Screaming, grabbing, kicking, hitting. Adam-djinni fought her, covered her mouth, and forced himself onto her. Iblisa hated her inability to look away, the way her disbelief manifested such revolting focus. It was sickening: the undisturbed nature of the hayplaces, the other djinn unmoving in their bipedal forms. The watching. The silence.

A violent incalescence ignited Iblisa. She screamed and lunged for the djinn. Her fists thud into their silhouettes, but they continued their show as if she were absent. The others pulled her away.

“Useless creations!” she shouted. “Shadows of nothing!”

They finished their motions, and Adam-djinni laid back to sleep as if he had done nothing at all. Eve-djinni took to her feet, and suddenly, in her hands was a large rock. She hovered over Adam-djinni’s slumbering body and lifted the object. Just as she was ready to throw it upon him, she collapsed, holding it to her chest. She laid on her side, away from him. Restless and fitful.

And so the djinn ended their performance, prostrating in front of Iblisa. The other silhouettes finally let go, their hands imprinted on her arms. They shrunk into their nebulous selves and disappeared into the trees.

The clouds were infernal. She thought she saw Eve’s face amongst them, then her human fingers snaking around the largest of the billows as though to hurl it downward. Iblisa cowered and awaited impact. Instead, a heavy breeze blew through her.

Was she afraid of Eve or her courage? Perhaps that was what Eve required: someone to sustain her wrath, understand its strength. Someone to recognize the hope behind the violence. Where the djinn had watched, Iblisa resolved to act. She would let Eve hold justice and be subject to her judgment. She unfurled into standing, searching the sky for Eve’s face to invite her smite. But Eve was no longer there.

Then she heard screams.

Iblisa raced with such speed that her lungs labored to fill. Upon arriving at Eve’s hayplace, she saw her lying fetal, the shade of the tree casting implacable darkness. Eve had changed. Her belly was round and swollen, the size of a water-bearing bucket. Iblisa laid down next to her and put a hand on her navel. Her skin was tight and leathery. A thumping came from within.

“What is this? What is inside?”

Eve moved her head only slightly, hair knotted and covering her face. “Adam—” she moaned. “I could not scream. He gripped me hard, and I tried to breathe. Tried to fill my lungs. My belly.” She lifted her fingers. “Tried to use my hands.”

She exhaled with a shudder—the kind of breath released after laborious weeping. Her body jolted and she cried out. She turned onto her back, digging her fingers into her belly. Water poured out of her parts below. And then began her bellows, as if expelling herself from her body. Her legs opened, and she took Iblisa’s hand and squeezed so hard Iblisa thought she heard bones snap. A golden light came from Eve. Iblisa knelt between her legs and her pink skin became blood- orange against the golden light.

Slowly, it appeared: a head, with gelatinous threads of hair. Instinctively, Iblisa put her hands under the creature, who was sliding out of Eve, bathed in the glow. A thick, violet vein connected the being to her, and it throbbed as if a heart. Iblisa bit the vein at its base, and the light faded. Eve secreted an object like a wide, crushed rose— pulpy with blood. The creature cried. Sharp, shrill, and wanting. Eve looked on, sweat at her forehead, her lips cracked—the skin under her eyes sagging with invisible weight.

She needed water.

Iblisa left the crying thing in Eve’s arms and hurried to gather buckets.

And there he was. Adam. Looking down into the Well.

Her tongue slid around her mouth with the cord’s residual sliminess. It was hot and bubbling—the same as her blood at the sight of him. Odious. Was he not an example of the dangers of creation? Where was his punishment for what he had forced unto Eve? For what he had put inside her? Not in Iblisa’s garden. Retribution was to be had.

She started for Adam, her body uncontrollable.

“What have I done now?” he asked. “Why are you looking at—”

Iblisa seized his throat. Throttled him until her nails broke his flesh. It was as easy as sticking a finger into rotten fruit. Hot ruby liquid. He threw up his hands and tried to push her away, but he was too weak. Too human.

Iblisa threw him into the Well and waited to hear the splash. No sounds came from its depths, but it didn’t matter, for she knew he was dead. She let her heart revel in its ugliness. What she had done was the only thing she could do. It was the righteous way.

She stared into the darkness of the Well. The pupil of a soulless eye.

The djinn reappeared before her, replaying the scene: Adam-djinni at the Well; him turning around; Iblisa-djinni strangling him; her tossing him away; her peering into the Well. Never had she witnessed herself outside of her being. At the same time as her actions frightened her, she believed there was power in monstrosity, in fearing oneself.

The djinn bowed and flourished away.

She took the bucket and sent it down into the Well. When she brought it up, the water was colder and clearer. The water of Jannah. Perfection.

The garden was wild with the sounds of the living. Iblisa let Eve drink from the bucket. Large, hungry gulps. The little being was still wailing. Iblisa then poured the remaining water onto them, using her hands to wash their bodies clean.

“Come into the sun,” she said. “You will both dry more easily.”

So they did.

Iblisa cradled them from behind and tried to keep them warm. Her heartbeat sped to the rhythm of Eve’s shivers. The longer they laid under the rays, the steadier their breathing became. She reveled in feeling small with them. Their synchronized heartbeats.

Thump, thump, thump, thump.

The sensation was fleeting and replaced by remorse when Iblisa remembered what act of Adam had made this moment possible. All she could hear thereafter was the suckling and gnawing of the voracious creature at Eve’s breast.

They finally dried, and Iblisa pushed the hay into the half-shade of a larger apple tree.

“Do not worry,” she told them. “I won’t go anywhere unless you require it of me.”

“More water,” Eve said.

And so Iblisa ventured to the Well again, content. Proud, even. It gave her purpose to defend and avenge those who could not. That she used the privileges the Voice had given her to rid the universe of Adam’s defects. The garden took a more golden hue, and it became the undertone of the azure sky, the emerald leaves. Iblisa admired the world around her—feeling blessed that it afforded her such dependability. The capacity to need and, now, to be needed.

She noticed, though, that no birds chirped. No butterflies fluttered. No djinn whispered.

There was the crunch of an apple.

It was Adam. Free of wounds. Entirely himself, as the Voice created him.

“How?” she yelled. “I made you gone!”

He continued eating and the Voice boomed above.

“Iblisa, I created you to care for this garden and its creatures. When I procured Adam and Eve, I intended for them to thrive under your guidance. I intended they would eventually find their independence. But you have done the unspeakable. You have attempted to take the life of one of my most precious creations. Why?”

Suddenly, Iblisa was no longer small. It terrified her feeling this giant and visible. And yet she had to relay her tale.

“He did not respect the garden nor its inhabitants,” Iblisa said. “He brutalized and betrayed Eve. I implore you to perform justice and teach him what is acceptable in this world.”

The crunching of the apple again.

“But he is imperfect!” the Voice boomed. “Even if I were to teach him, he would act otherwise. Is that not what you also do, Iblisa? Don’t you, too, have the ability to act in any way you would so like? It is a gift I have given you. It is a gift both you and Adam share.”

“And Eve,” said Iblisa.

“And Eve,” said the Voice. “And what you did for her was undeniably miraculous. You held the first human baby, brought it into this world. Yet, you tried to kill Adam. How do I adjust for this matter?”

Another crunch of the apple. Iblisa loathed Adam’s face—its absence of expression, the dullness in its pupils. The golden hue that once washed the world faded in his presence. She clenched her fists.

“He caused the death of the bee colony!”

“And is there no such thing as an accident?” asked the Voice. “To kill with intention, as you have, is a different matter.”

“You cannot deny that I gave Eve her life when I did what I did. I acted out of integrity.”

“Iblisa,” the Voice said. “It was not your choice to make. You are not the sole entity to decide what is or is not just.”

She eyed the Well and the bucket beside it. Adam was walking near the Old World Sycamore, the gold of its leaves glittering. “So be it. Now, I really must get water. I must care for Eve and her creature.”

“I fear you cannot,” the Voice said. “There are no more actions I may permit you in Jannah.”

Iblisa keeled over, a stabbing from within. She looked at Adam and the Sycamore. No leaf laid on the ground. No leaf in his hand. The tree had not been touched, yet a fire burned through her.

“But I am the keeper of the garden! I watered these trees and plucked their fruit. I cared for the djinn. I admired the butterflies and mourned the bees. Everything you see here will wither without me! Eve will wither without me.”

“They will find their way,” the Voice said.

Tears ran down Iblisa’s face. She tried to wipe them, but there was no stopping the flooding.

Iblisa heard crying—a high-pitched and rattling sound. The woes of a human baby.

The wind lifted and took her. The baby’s wailing vanished, as did the garden.

Iblisa was plummeting through the air. Hurtling. She fell the only way a being like her could: less like a bird, and more like a person—heavy and alone.

She did not sense her landing, just that the chaos stopped. All went black except for a hole above. It revealed the deep blue of a sky. Green leaves flickering with gold. She sat in cold water, and her slight movements echoed in the vertical tunnel. Rivulets seeped from a couple of holes in the stone walls.

Beside her was a bucket. It was then that she knew she’d never be thirsty. Not because she had water, but because she resolved never to drink it again.

Human speech reverberated down the Well. A woman’s voice.

“Eve!” Iblisa called up. “Save me! Send the rope!” Instead of Eve, she saw shadows. The djinn.

Looming, shrinking. Heat pricked Iblisa’s ears and neck, knotted her throat; she was ready to shout her fury but had already exhausted herself. If they did not help then, they would not help now—they were of spirit and not of heart. Who was left to hear her?

Unable to go up, Iblisa resolved to find elsewhere.

She dug a finger between the stones, carving around their edges until she pried one out. Behind it was the end of a root with thin and spiraling tendrils. Same as the Sycamore leaves, it pulsed gold. She wondered if her blood was the same color.

Desperately, she bore past the roots, through the trails of worms and nests of earwigs, under the homes of rabbits and moles, around pockets of gold and silver. When she broke through ground into air, she found she was still in the Well. This time, there was a hive and bees—sprouting from the side of the tunnel above, just out of Iblisa’s grasp. She reached for them, regardless. One honeybee leapt onto her hand. Roamed her skin as if Iblisa were its home. How monstrous it was to have such a precarious bond, she thought. To have been a keeper. To have been chosen to keep. To have been chosen at all.

She cupped the tiny being and held it to her heart.

Thump, thump. Thump, thump.