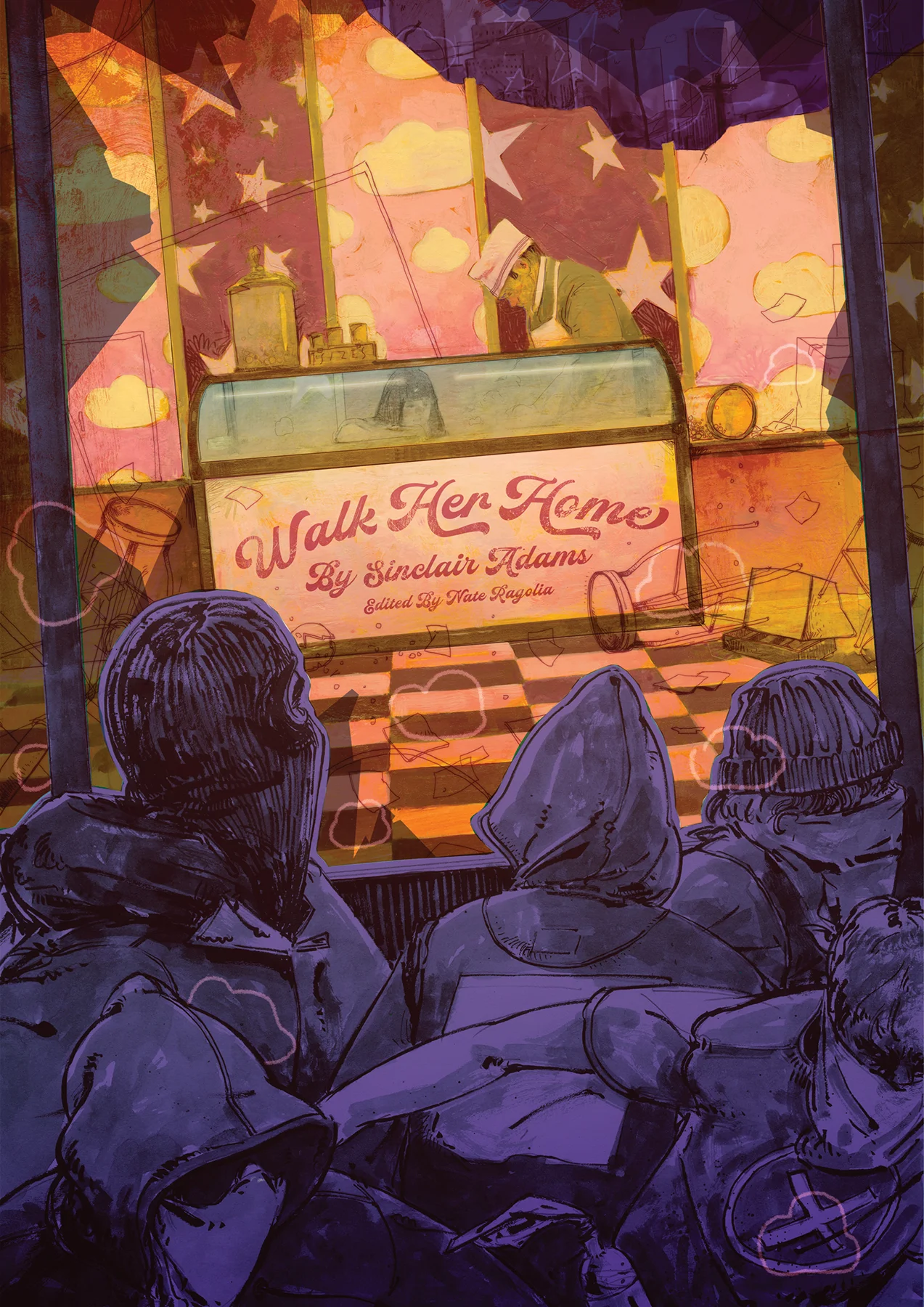

Underwater Fireflies

2062.03.15 06:32

Solitude Probe reporting back to Bright Futures Inc.

Successful landing: Enceladus, moon of Saturn Data stream active

7326 m of ice breached

Molecular scan complete: Confirmed H2O with NaCl

Scanning for lifeforms

When the probe started transmitting data, the busy Exoplanet lab went still for the first time in months as the entire team held their collective breath. One might think it was because the probe had been travelling for years and the scientists were experiencing a moment of reverence and gratitude for their success. Or perhaps they were eager to see if their various hypotheses would be proven correct. Both true, as far as they went. However, the bigger reason was the time-honored tradition of betting on mission outcomes; there was a surprising amount of money riding on this particular probe.

The only one not leaning in was the team manager, Dr. Elliot. Her lead tech, Frank, knew she disapproved of betting but didn’t know quite how many lifeless planets she had seen come and go. She tended to reserve her excitement for either petty bureaucratic victories or real scientific advances. Though she couldn’t remember the last time she’d felt breathless enthusiasm for her own work. Really, she should have quit Bright Futures Inc. after the fiasco on Ganymede.

She brushed her hair out of her eyes and squinted.

“Is it coming through?” she asked, as the team crowded around the monitors.

There were reasons they needed to find something, anything. Bright Futures’ deep-sea mining equipment was already flying toward Saturn, so the company was rushing to get their extraterrestrial assessments done before the big rig entered the planet’s orbit in two years. Time was running out for anything living in its path. The assessments were critical in determining where the developers would be allowed to destroy and disrupt, where they would be allowed to dig.

It was Go Time after all the waiting. Now there was a verified stream of data pouring in and soon there would be audio and video feed. Instead of excitement though, Dr. Elliot fought

off a familiar sense of dread. But so far, nothing but darkness and silence. That was to be expected with the amount of ice packed above the probe. It would take a while.

“Turn up the volume, Frank,” Dr. Elliot said, gesturing at the screen.

After fiddling with the sound and getting nothing, Frank pulled up the betting scorecard and started checking the early spreads.

“Salt water… who had salt water?” Frank scrolled through the spreadsheet and started calling out names. Twenty-one out of twenty-five of them had expected salt water.

“What else?” asked Dr. Elliot, ignoring the betting tally. “How long till the lifeform scan is complete? And what range is it reporting?”

“Range is less than a centimeter right now, no lifeform detected,” said Frank. She nodded absently. With the night vision capability of the probe’s camera, they should get a decent visual soon. Could they be looking at alien life in a few hours? And would it be sentient? What Earth creature would it resemble? Though she disapproved of gambling, she had to admit that she understood the impulse. So much of their life’s work depended on luck.

Throughout her entire career, there had been so few chances to find alien life. They had found anaerobic bacteria on Phobos and microbes on Ganymede, fat lot of good that did them. They had proudly reported “Level 1: Life” in their extraterrestrial assessment and recommended further study. But Bright Futures Inc. wasn’t interested in microbes when they got in the way of collecting rare metals.

That was when Dr. Elliot first started feeling tired.

To halt development, to protect life, you had to have “Level 2: Sentience.” That huge milestone was what it took to freeze mining in its tracks and get researchers sent in instead. Researchers could then evaluate for “Level 3: Society,” and even the not-yet-found but often dreamed of “Level 4: Civilization,” demarcated by technology and higher thinking.

Of course, the Exoplanet Team didn’t care about mining at all. They were in it for the big alien discovery: first contact stuff, like in the old movies. The bar had been set so high. Everyone wanted space whales. Everyone wanted little green men who could speak English. Everyone wanted squiggly creatures in spaceships.

Frank scrolled through the betting spreadsheet. A long list of scientists’ names followed “Cephalopod” on the betting chart. Everyone leaned in, wanting tentacles.

There was a tang in the water, something had changed. We tasted the change and were curious. Rising carefully, our scouts drifted to the front. Clinging and then releasing our neighbours, we reached. A slight bitterness as some of us let go and left us, but we clung to who remained and wished the explorers well. Then we waited impatiently, concern radiating out and over the curiosity.

A buzzing, as heat ran up, and down, and through, with ripples as the currents tugged us this way and that. We reached out and out, seeking our scouts and finally rejoined some but not all. We tallied the lost, embraced the returned. As we became whole again, swirls of sweet greeted us, then an odd hint of metallic ice. A new taste for the palate. Fascinating. Something new had arrived in the world.

2062.03.15 23:47

Solitude Probe reporting back

Visual image attained

A video feed of dark nothingness pinged back for several hours. Darkness, and a few effervescent bubbles. Nonetheless, the team stayed. Stayed and stared and tried to manifest something. Anything.

“Nothing on visual?” Dr. Elliot was calm and methodical. Frank shook his head.

“No—but the probe should automatically adjust for night vision. It’s darker than outer space down there.” Minutes passed, then a soft ping began, and numbers and letters flew up the screen.

“Look!” Frank’s voice rang out. “Something’s coming through!”

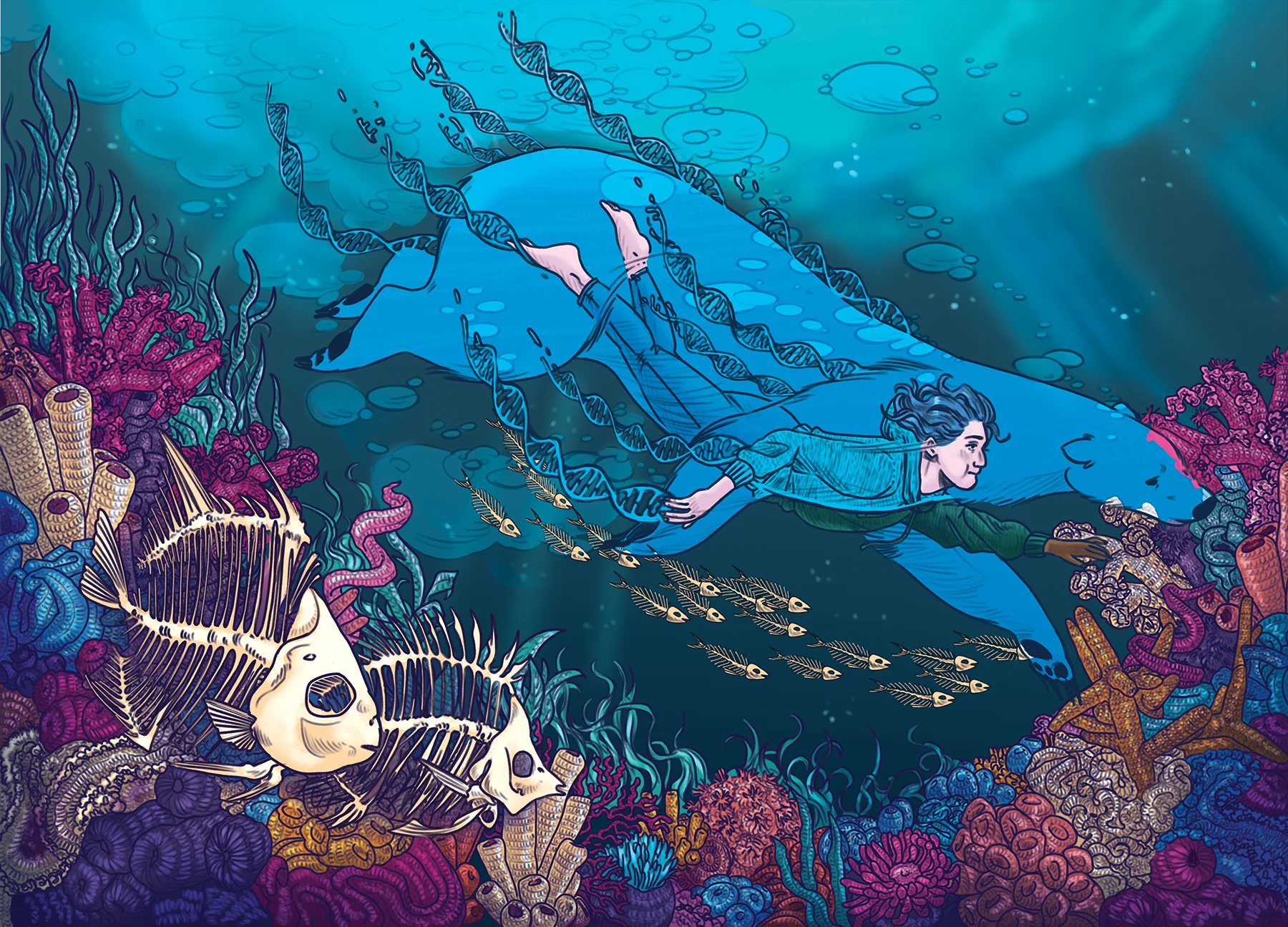

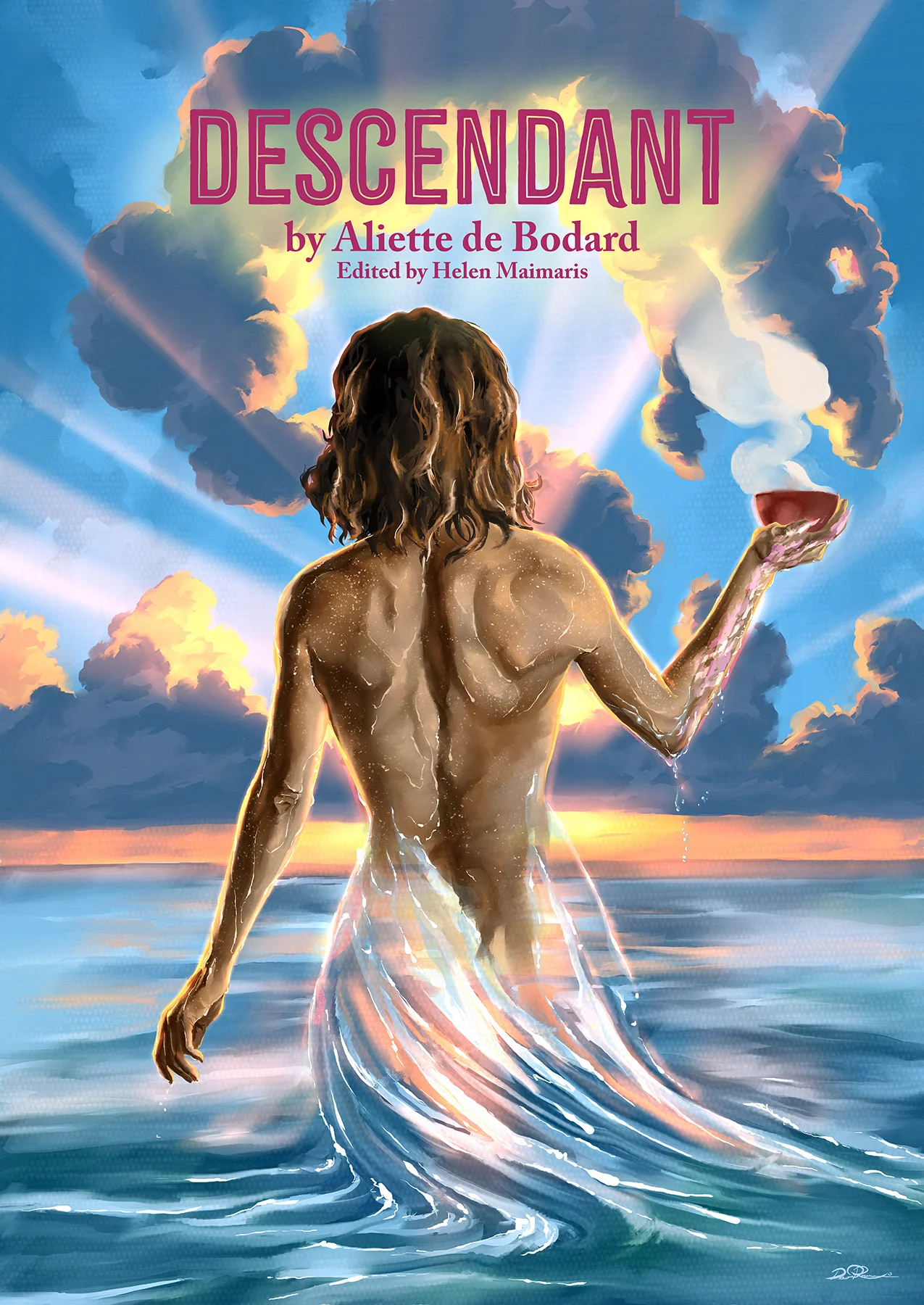

As they watched, the dark screen lit up. Tiny pinpricks of blue light, swirling like fireflies. There was a swish of cyan, followed by a flash of pulsing fuchsia. A discernible pattern. But what did it mean?

The long-forgotten thrill of discovery shot up Dr. Elliot’s spine and she took a deep breath. Please, please, she thought, let this be different.

“What is it?” Dr. Elliot whispered.

Someone checked the spreadsheet. Seven people had bet on “Bioluminescent Signature,” including Frank.

Dr. Elliot felt her bone-deep tiredness begin to fall away.

The scouts were buzzing with excitement at the new thing. A metallic tang, smooth and sharp, but not cold. It had its own glow at one end of the cylindrical thing. We had embraced the new object and it had bitten us, dissolved us. A red-hot sensation, a burnt taste, and the remaining scouts had broken free and sailed back to our main body to report on the novelty, to report on the loss. It was dangerous, but what was it?

We approached, the young of our sparkle rushing ahead, the elders holding back. “Don’t touch the hot end,” we shared guidance up and down and out. We drifted, then sailed forward to intercept.

The strange thing was coming toward us, powered by something beyond the currents of the water. A flash of warning rushed through us but the young did not falter. They approached, sailing in and around, a gentle buzz of greeting, a sweet welcome. Fearless, and we were proud.

A young bud touched the glowing tip and evaporated in an eruption of pain. We let go, considering.

2062.03.16 15:21

Solitude Probe reporting back

Cellular sample attained... Analyzing

The images of winking lights continued for hours, intensifying. Like fireflies, but swimming. Or sailing? Was it just organic material drifting in ocean currents? Or were they sentient? Was it alien life? This could be bigger than when alien crabs had been found at the bottom of Europa’s ocean. Were the lights tiny creatures or spots on a larger animal? Nothing was conclusive yet, but Dr. Elliot already imagined a swarm of life in front of her. She felt the burnt-out husk of her bureaucratic career slip away as the scientist leaned in. Excited again for the first time in years, she grinned and touched the screen, willing the flashing lights to resolve into a sign.

The bioluminescent creatures wavered, dove, then circled back, like a susurration of the starlings of old. From cerulean to indigo and then deepening to magenta, the tiny dots wept across and around the screen. The fireflies were putting on a show. But was it intentional or incidental? It looked thoughtful, purposeful. Like the entire flock moved as one.

Dr. Elliot did not sleep. No one went home. Years of waiting and they were on the cusp of a grand discovery, they all felt it. The day passed, the data stream sharing new information about the alien ocean.

“We’re receiving more data,” Frank said. “Looks like it’s evaluating a substance, something on the probe. We have a sample analysis coming through.” Everyone held their breath. “It has a DNA signature,” he said. “It’s a complex organism.” There was a somber silence as the scientists took that in. “We have alien life. Multiple individuals.” Cheers erupted.

Dr. Elliot whooped along with the team. People hugged, some even cried.

Frank was too busy to check the spreadsheet, but someone did. Twenty people had bet on finding lifeforms. No wonder, really, it was what drove them; it was the dream that powered their lives.

Dr. Elliot squinted. “But who are you?” she asked the data streaming past. “Sentient?”

Frank stared hard at the screen. “The cellular analysis says it’s similar to the animal kingdom on Earth, somewhere between gastropod and… marine algae? What does that mean? Swimming snails?… That form toxic clouds like marine algae?” he shook head. “That’s wild.”

Someone pulled up the betting spreadsheet again. Zero takers for algae, two takers for gastropods. Two people across the room laughed and high-fived. Frank had cephalopods or fish on his list, nothing related to what they were seeing. And “sentient algae?” Well, no one had called that.

“The movement of the lights is not consistent with the currents we’re detecting,” Frank continued reporting on the data analysis. “They appear to be moving of their own volition. They’re alive and capable of independent movement. It’s not just little spots of light.” They all watched the glowing patterns on the display.

“They’re practically using morse code,” Dr. Elliot said. “I wish we could direct the probe in real-time instead of just receiving data. We could have a conversation—I know we could.” Her voice was light and her eyes shone, filled with wonder.

After some reflection, we strained toward the strange new thing again, curiosity overcoming the danger. Was it alive? Could it speak to us? It was clearly “other.” But “other” from where and from whom? Was it a thinking creature? Could it communicate? We knew only our world, but we could imagine new things, new tastes, new sensations. Perhaps this thing was alive and thinking. We needed to know. We embraced the danger.

We tasted, we welcomed, we embraced.

And the strange thing… did nothing but blink and sting us.

No change in texture, no change in taste. Just a dead blinking thing, like a tiny volcano eruption. No thought. No response.

We considered.

2062.03.17 09:54

Solitude Probe reporting back

Data stream intact

Dr. Elliot watched the blinking lights on the screen and imagined they were dancing. Imagined they were creatures who felt happiness, felt pain. She longed for a sign of sentience, anything she could put in the way of the deadly machinery powering toward their moon. The fireflies could be intelligent and capable of self-awareness. Capable of making decisions. Potentially capable of communication.

Watching the swirling, blinking dots growing in brilliance until they took up most of the screen, tiny undulating blobs becoming visible, she could imagine a greeting. Outreach. All the fireflies acting in unison, purposeful.

“Let’s look at this backward,” she said to her team. “If these little lights were sentient, what would they do? How would they act? And how would they be moving?”

“Jet propulsion, maybe?” Frank said. “Like hundreds of tiny jellyfish or octopuses?” He checked the spreadsheet. Fourteen people had bet on “Fins” for mobility, one had bet on “Salt Water Jet Propulsion” and no one had bet on “Cilia,” but Frank was thinking creatively now.

Dr. Elliot was already composing her report in her head. They’d need more data to make a convincing argument for sentience. It was one thing to demonstrate that the blinking life forms were alive, quite another that they were capable of independent thought and feeling. If the probe took another twenty-eight days to circumnavigate the moon’s ocean at a depth of one to ten meters under the ice, they could map out an entire upper ecosystem. What did the fireflies eat? Other animals? Were they scavengers, predators? Were there similarities to Earth’s oceans or was the moon’s habitat truly alien? They could learn so much! She could save them. She just needed more data, more time.

A gasp from Frank brought Dr. Elliot’s attention back to her team. “Data stream inconsistent. Something is happening.”

The scientists crowded back around the monitors. The entire screen flashed turquoise, then cyan, then crimson. It flared for a moment then went dark. No more twinkles.

“Ah, crap!” came a voice from the back of the room.

“We’ve lost visuals,” said Frank, unnecessarily.

For a few minutes, data continued to flow, the image display a stream of numbers and letters. Then they started to waver, chunks missing, empty spaces rolling up the monitor. “We have a thin layer of life around the probe,” Frank reported. “We’re surrounded by the lifeform. This is a pretty weird kind of algae, it’s gumming up the works. We can’t receive cleanly anymore. I think we’ve lost the propellor. The probe is behaving erratically.”

The stream of data continued but the information had changed. “Still salt water, but the composition is changing, and the temperature is dropping. I think the probe is malfunctioning. It shouldn’t be doing this.” Frank fiddled with the data stream and peered at the monitor. “Wait, the pressure around the probe is changing. It’s increasing. The propulsion system can’t regulate its position. We can’t detect the lifeform anymore. No! I don’t think the algae likes us. Is it attacking the probe?”

No, thought Dr. Elliot. Please, no. They needed more time. She thought about the mining equipment zooming on its way, thought about Bright Futures Inc. and the destruction they would bring. She stared at the monitor and silently begged the lines of numbers and letters to keep coming.

The thing was not a thinking thing. It was not alive. It was not something that communicated. Its flavors did not alter. It did not have moods. It did not have feelings. And it was a danger to us. The course forward was clear.

We engulfed the strange cylinder and squeezed. Different hums coming together for a common purpose, even when those of us closest to the sharp lifeless thing were burnt. We squeezed, coating the cylinder and tasting, tasting. The hot light went out. The thing was dead but had always been dead. And as it fell away, it started to skitter sideways. We gripped firmly and some of us dove, stretching downward where the ocean would press it in. Finally, we let go, reaching upwards. The thing would trouble us no more.

2062.03.17 10:09

Solitude Probe reporting back

Data stream inconsistent

“I think the algae killed the probe!” Frank’s voice cracked.

Fireflies, not algae, thought Dr. Elliot. She sighed as the monitor reflected the building pressure, the plunge downward. The data stream ended abruptly—the sensors must have bent in on themselves and the transmitter collapsed. She caught her breath and fought the urge to weep.

As she stared at the monitor, blinking back tears, she had a thought. “Wait, play the last visual back again,” she said. As she watched the swirling dots, all her seemingly wasted years analyzing exoplanet data coalesced into an observation, an idea.

“Do you see it?” she whispered, her heart beating faster. No one answered. An intuitive leap is not logical. Not predictable. An intuitive leap is the human brain rearranging known facts and seeing a bigger picture. And the bigger picture was staring back at her, dancing on her retinas. “I see it,” she whispered, so low that no one heard her.

The swirling lights weren’t little bugs or birds acting individually, they were part of a larger, singular intelligence, she was sure. There was sentience, there, oh yes, and of an entirely alien kind. She had always dreamed of encountering something entirely new, unexpected. Something that humanity’s tiny imagination had missed. And that something was practically smiling at her on screen. Well, maybe not smiling, since it had gutted their probe, but it was still a greeting of sorts. A pang of compassion for the being they had disturbed pricked her, followed by a wave of elation. After all this time, there it was, her big discovery. And Bright Futures Inc. might destroy its home. She felt something like grief flood through her.

“I’m calling it!” said Frank, doing the calculations. “Fifty-one hours and thirty- nine minutes of data feed. Who had ‘Probe Malfunction on third day’ in the pool?” Three people did, but no one cheered. The probe’s destruction ended their data collection and even the winners weren’t happy with that. Someone made a joke about killer algae. I’ll always think of them as fireflies, thought Dr. Elliot.

Excitement over, the data stream terminated, the scientists went home, saw their families, went out for celebratory drinks, caught up on sleep.

Except for Dr. Elliot, who, mindful of the mining equipment churning through space, argued with the astrobiologists about unified consciousness and hive minds. The alien fireflies were given a random name that no one but Dr. Elliot and the astrobiologists remembered. The exo-ecologists said there wasn’t enough data to confirm an ecosystem, although the presence of the fireflies suggested there had to be one. Days passed, and Dr. Elliot pushed for a broad finding when she sent in her draft assessment for approval. “Firefly species, most likely sentient. Further study and evaluation needed before the moon is developed, either for resource extraction or settlement. Final Recommendation: further study before development proceeds.” She waited.

A few weeks later the finalized report came back: “Lifeform detected. Evidence is inconclusive on sentience. More study needed before a sentience reading can be confirmed. Degree of accuracy estimated at low to moderate. Extraterrestrial Assessment conclusion: Enceladus is provisionally cleared for development.”

Typical. But instead of retreating in her usual caustic defeat, Dr. Elliot stayed late at the lab, energized. Not on her watch, no way. Not again. She drafted up a new request and insisted on redirecting another of the company’s probes to investigate whether sentient marine algae lived on Enceladus. She wanted to meet the fireflies again. Who knew? Maybe the life cycle of the firefly alien was complete in days and there would be the equivalent of a billion years of evolution before they even arrived for their next visit.

Before she put the final report away, she closed her eyes and let her imagination stray back to the frozen moon. She saw the dark ocean depths and wondered how a sentient lifeform experienced such a dark and crushing place. She wondered what had lurked just beyond the probe’s scope, what wonders beyond her comprehension or perception might live there. She pictured a full ecosystem of creatures under pressure, deep-sea monsters and delights with the fireflies as shepherd, the fireflies as predator. Just beyond the probe’s night vision, what new kingdoms waited?

She rewatched the video of the fireflies again and again, imagining she could decipher their blinking and converse with them if she just stared long enough. She found herself gazing at stars at night, imagining them swirling, then flashing blue and pink. She was entranced, re-invigorated. Someday, she promised the fireflies.

We remembered. Even long after the thing had plunged to the depths and bothered us no more. We wondered and considered the mystery. We remembered. We didn’t understand, not yet. But someday perhaps we would. We waited for something new that could help us understand. We remembered, we would be ready. We stretched out and sailed on, still considering, and hoping.

Dr. Elliot turned to the next project with something like joy. The probe she had redirected to the fireflies’ home moon would land in about nine months. In the meantime, there were three more probes scheduled to land on other moons of Saturn, so at least one new data stream was expected to start soon. Surely one of them would pay off. Optimists were calling for another frozen ocean.

Frank was taking new bets and filling up a fresh spreadsheet.

“Hey Frank,” she called. “Put me down for Sentience. And maybe something with tentacles.”