April Staff Picks

Nate Ragolia

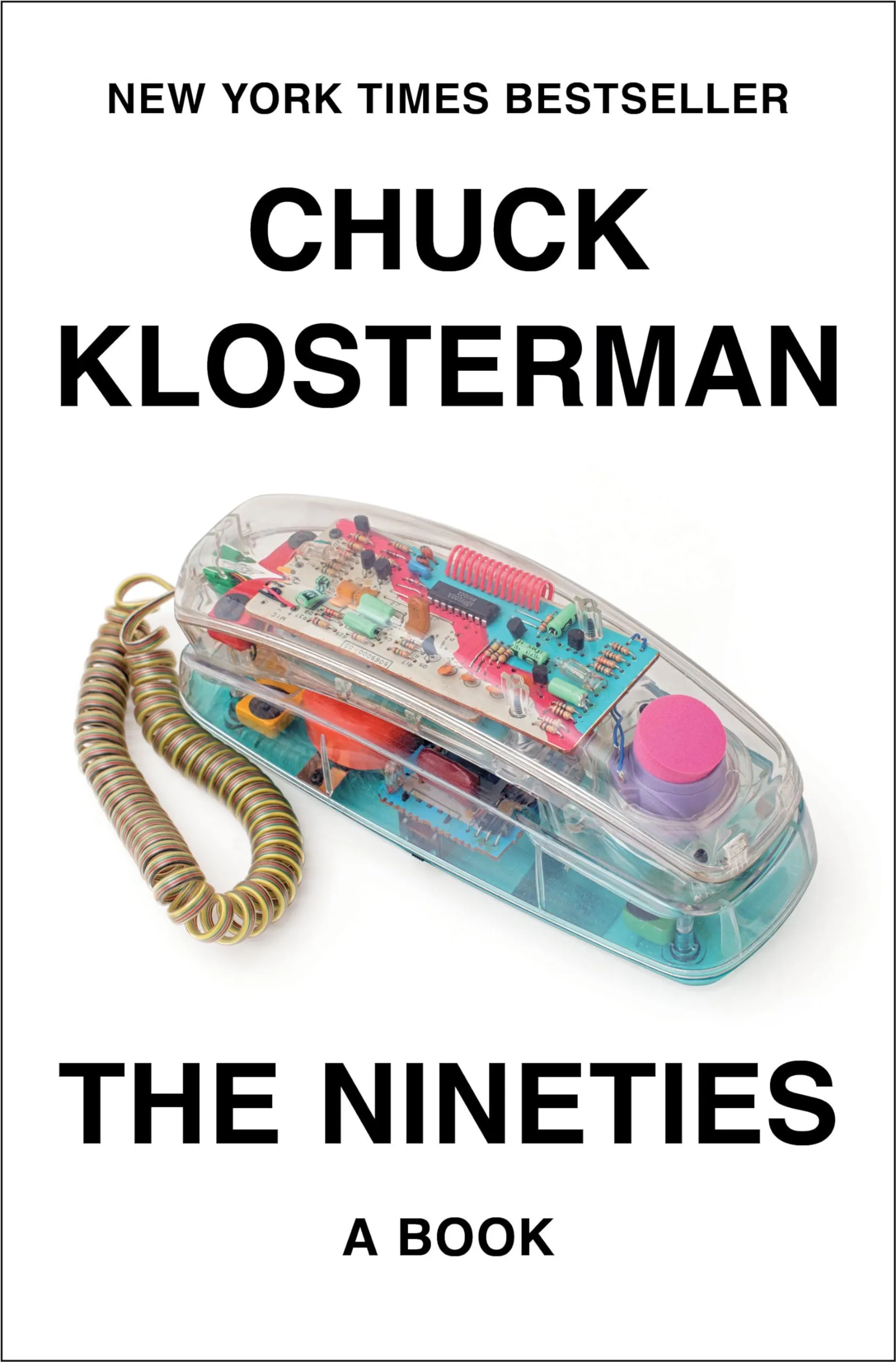

The Nineties: A Book

As someone born in the early eighties (Yes, we have a couple of oldies here at F(r)iction), the 1990s holds a special place in my heart. It was a “simpler time” in that we had still had a monoculture, even as it saw massive changes to how war was done, how the global economy was shaped, how we viewed race, gender, and sexuality, how politics would change irreversibly, how we’d confront terrorism, gun violence, cloning, the fall of Communism, and more… And that was before the internet even took shape.

To process just how complex the world of my teenage years really was, I’ve been reading Chuck Klosterman’s 2022 book The Nineties. Klosterman’s thoughtful dissection of the era from Ross Perot to Michael Jordan’s retirement and unretirement to the Unabomber to Dolly the Sheep to The Matrix is riveting, not just because I lived it but precisely because living in the moment means missing so much. And that was especially true in a time when the news showed up in paper each morning or on TV briefly at night, but wasn’t the constant mood that it is in 2025.

If you’re seeking solace in near history and the lessons we could have learned, and maybe still can, this book might be for you. And if you just want to reminisce about Nirvana, early Tarantino, and the O.J. Simpson trial this book will hit the spot.

Sara Santistevan

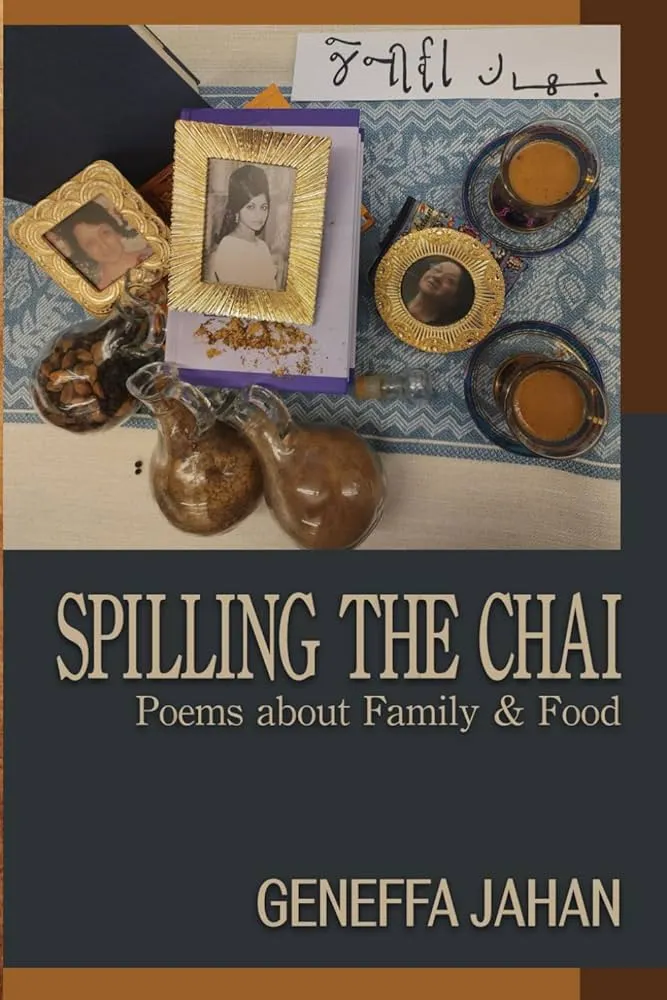

Spilling the Chai

April is National Poetry Month, which means I’m more than inspired to read satiating poetry that leads me to the following question: What ingredients make a poem “good?” Pungent imagery, spicy metaphors, and a gut-punch ending that lingers immediately come to mind. So when I saw chocolate mints the other day and immediately thought not of Olive Garden, but rather, “the paradox of a chocolate mint / sweet and sharp / each flavor balancing / the excess of the other / like we used to do as people,” from Geneffa Jahan’s poem “Chocolate Mints,” I knew I had to revisit her delicious debut collection Spilling the Chai.

“Chocolate Mints,” like all the poems in this collection, uses food as a conduit to ask existential questions: how our cultural identities flavor our (mis)treatment in society, how complicated family histories echo in our present, and how the languages we grow up with can shape our understanding of life. What strikes me most about Jahan’s poetry is her play with language as both a poetic and therapeutic practice. Growing up in a multilingual, cross-cultural household, Jahan learned to speak a dialect entirely unique to her family, now wielding it as a tool to excavate emotional truths.

What I could say about this book would fill a seven-course meal, but instead I’ll leave you with an amuse-bouche to entice you to savor the collection yourself: the opening and closing lines from Jahan’s poem “Dizzy Means Banana,”* which showcase her stunning wordplay across languages:

“To my failing ears, chakkar and chakra sound the same / Chakkar the spinning of one’s head, crystals dislodged from the inner ear throwing the body off-kilter. // Chakra pronounced almost the same, a spinning of wheels within the body…//…In our house / dizzy meant banana, / and I could safely say I didn’t want one, / pale and raw, difficult to swallow / the texture of chalk / but easier to reject / than the / hand flying out / to tame my face.”

*“Pronounced “dizzy,” ndizi is the Swahili word for banana” (Jahan 4n2).

Dominic Loise

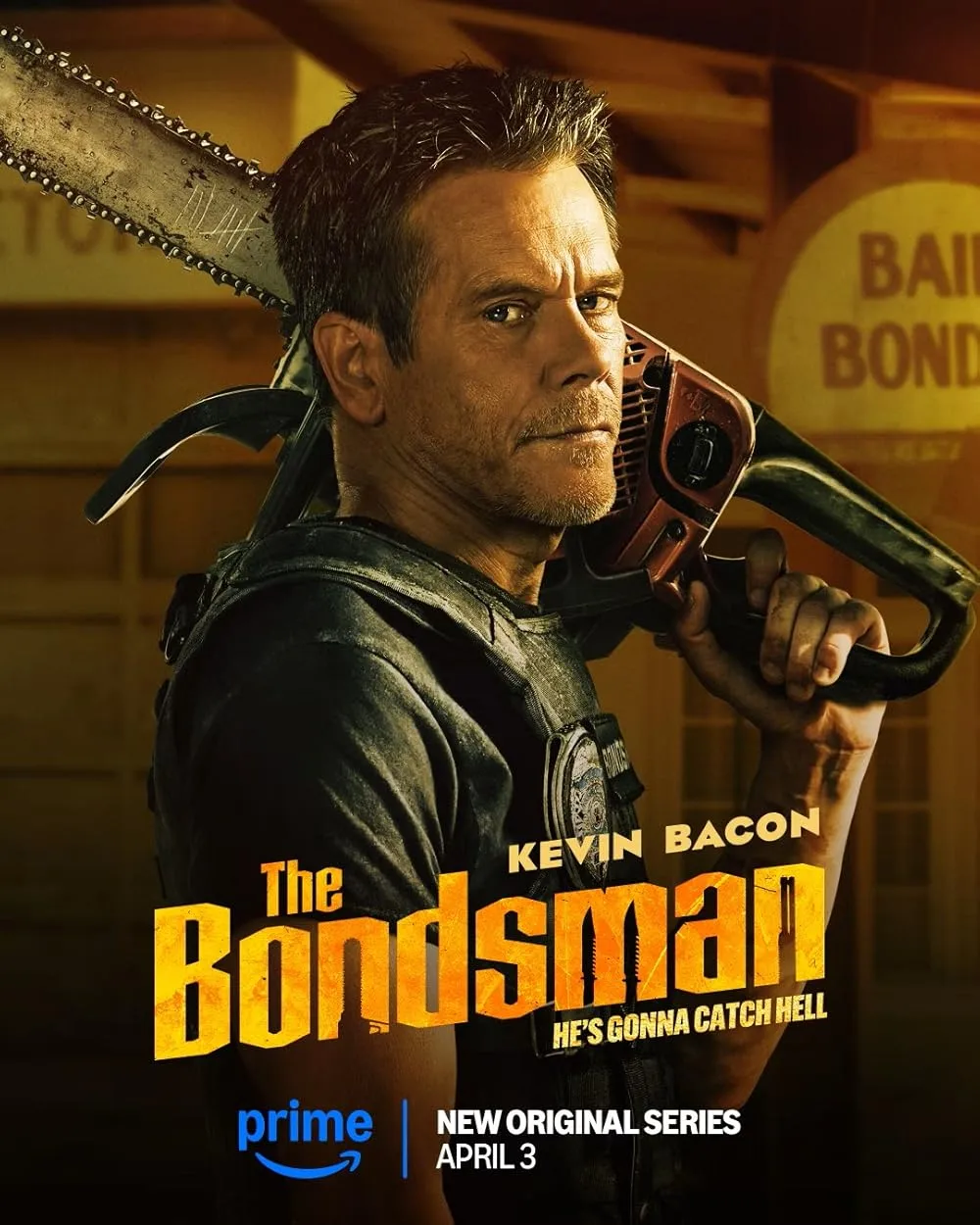

The Bondsman

The Bondsman is a new streaming show from horror production studio Blumhouse starring Kevin Bacon. The premise is similar to the television series Reaper or the movie RIPD, where the main character, here the recently deceased bounty hunter Hub Halloran, now collects escaped souls from Hell on Earth for The Devil.

Hell works on a pyramid scheme for collecting souls and communicates via analog fax machines. Also, the episodes are incredibly binge-able as they flow into each other like chapters in a book. And the strength of The Bondsman is the bigger story it tells is Hub’s estrangment from family and whether he’ll be able to make amends with them.

Speaking of Hub’s family, a special shout out to Beth Grant, who plays his mother. I have been excited every time she has been in something ever since I saw her in Donnie Darko. Grant delivers an amazing performance as someone who both taught her son the bounty hunter business yet feels she failed him as a mother since he went to Hell when he died.

Ari Iscariot

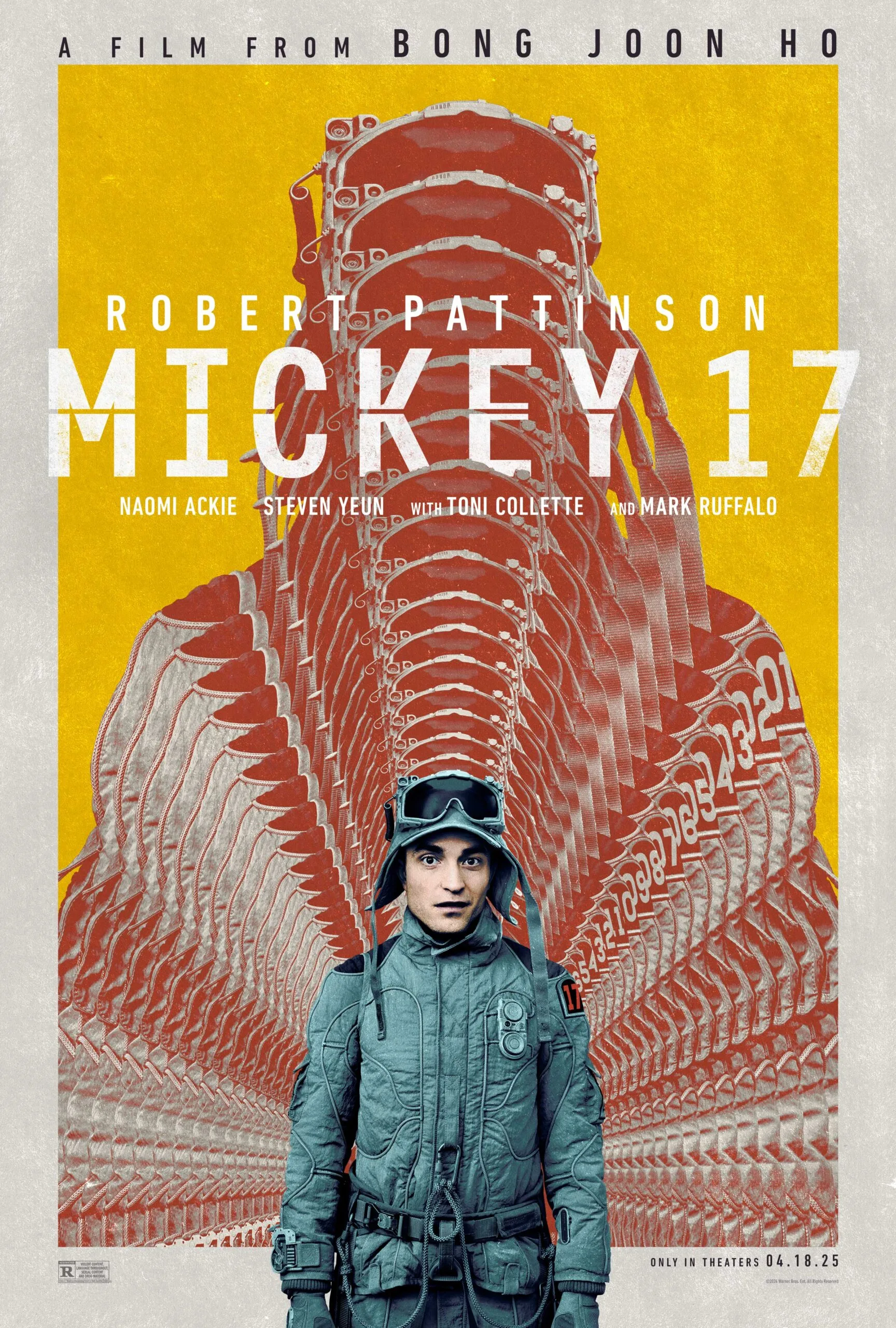

Mickey 17

So… Mickey 17. The trailer was weird, the advertising was weird, and the vibe was weird overall. But is it the kind of weird you wanna watch? Keeping vague on the plot details, allow me the honor of making my case through the acting, the characters, the color palette, and the messaging.

Throughout his career, Robert Pattinson seems to be building a repertoire of playing weird little guys. And Mickey, our protagonist, is a weird little guy. Fun weird. Put him under a microscope and do experiments on him weird. (Ironically, the same attitude pretty much everyone else in the movie has towards him, as Mickey is a disposable clone that can be replicated endlessly.) Flexing his weird little guy skills, Pattinson delivers a mind-boggling performance as two identical characters, the likes of which I haven’t seen since Lindsay Lohan in The Parent Trap. The distinctions between the two versions of Mickey are so clearly delineated: down to body language, personality, voice, line delivery, etc., that you have to actively remind yourself Pattinson doesn’t have a clone in real life.

In contrast to Robert Pattinson’s one man circus, we have Mickey’s partner, Nasha, played by Naomi Ackie. She perfectly compliments the pathetic, scraggly, wet-cat energy Pattinson exudes with her blunt confidence and care. One of the things I love about this dynamic is that Nasha is the rock in Mickey’s life. She’s the protector; she’s the brash, outspoken one; she’s the one ready to pick up arms and fight everyone to the death to make sure her poor little meow meow isn’t being abused. It’s a very delicious subversion of heteropatriarchal gender roles. (She also wants to fuck both clone versions of Mickey at the same time, and the movie does not slut shame her for this. It’s like Yeah. Obviously you would want to fuck two versions of Robert Pattinson. Wouldn’t we all? And I applaud them for saying that with their whole chests out.)

We also have Mark Ruffalo playing one of the villains. A perfectly creepy sleaze, his depiction of the politician Kenneth Marshall obviously apes the mannerisms and behavior of Trump and Musk. (And also, strangely, incorporates a heaping dollop of Marlon Brando’s The Godfather.) Suffice to say, Mark Ruffalo was having a grand old time playing the egomaniacal, narcissistic patriarch and you can feel the sheer joy he’s taking in the blatant mockery of the current state of politics.

To the point of color, there’s a lot of grays and off-whites in this movie as a consequence of the dominant setting being a futuristic, dystopian-esque spaceship. The lower-class members of the spaceship mostly exist in these spaces, devoid of coloring in gray or black jumpsuits, or washed out by white lab coats. In contrast, the rich characters’ clothes are very colorful and their spaces are glaringly opulent. But even in the lower class areas that Mickey, Nasha, and the rest of the crew populate, we still have lighting that is often vibrant and tonally poignant. (At one point, I turned to my partner and I was like Hey, I know I said this in the last movie we watched together but honestly, people don’t use yellow lighting enough and it’s really good in this movie. And she was like Haha. Yeah, I wonder if it’s the same guy who directed the last movie. Spoilers, it was the same guy. The cinematographer for Snowpiercer is not the cinematographer for Mickey 17, so I think this particular brand of yellow lighting is just Bong Joon Ho’s thing. Wild to be able to recognize a guy by the colors he uses in his films.) Anyway, the film has excellent environmental storytelling through color and costuming that rewards those who pay attention to those details.

Finally, and most importantly, this was a movie with a very satisfying ending. In an industry that seems ever more focused on fast-paced action, big displays of grandiose (and shitty) CGI, or high octane emotions without any impactful character arcs or messaging, a well-rounded plot is extremely refreshing. The recurring plot points in the film are built upon and resolved and Mickey’s personal arc and struggle are compassionately and directly addressed in a way that, once again, rewards the audience for their attention.

In conclusion, is Mickey 17 a weird movie? Yes. Is it going to be for everyone? No. But if you’re looking for a strange, heartfelt sci-fi romp that wraps up everything neatly and sweetly in a bow, has an incredibly diverse and colorful cast of characters, and keeps you interested for every single second that it’s playing, Mickey 17 is for you.