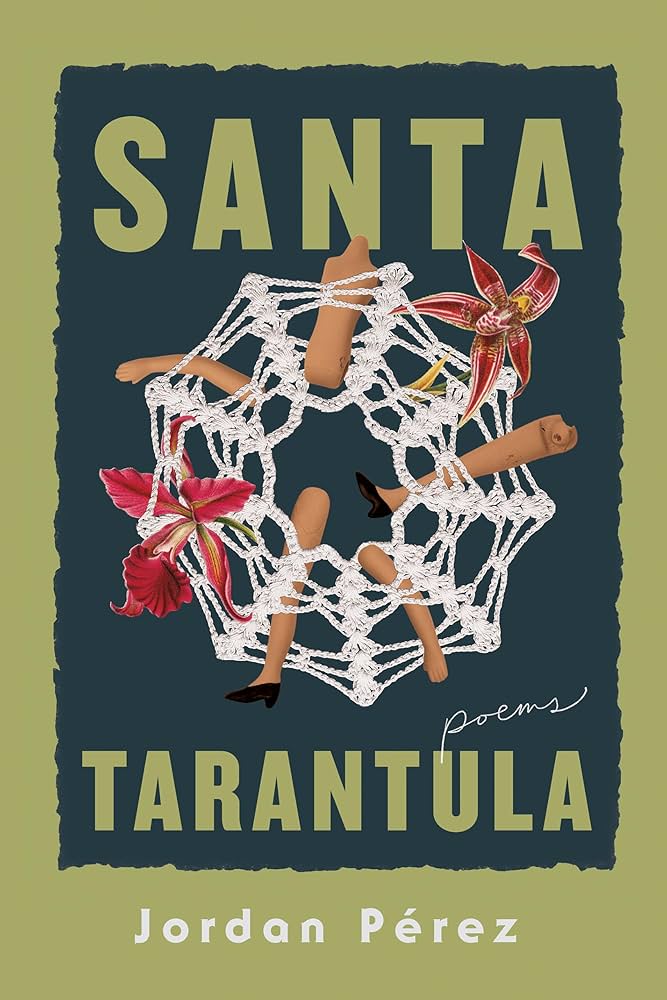

A Review of Santa Tarantula by Jordan Pérez

Published on February 1, 2024 by University of Notre Dame Press.

Upon discovering Jordan Pérez’s award-winning poem “Santa Tarantula,” my immediate instinct was to share it with every poetry-enthusiast I know. Pérez’s command of hypnotic alliteration and masterful weaving of technical language from the fields of arachnology, religion, and capital punishment create a haunting statement on womanhood. Her debut collection, Santa Tarantula, mirrors the themes encapsulated in its eponymous poem: the connection between women and the natural world; the oppression that occurs in Biblical narratives, patriarchal governments, and intimate relationships; and the urgent need to dismantle the legacy of silence.

Divided into three sections—”Smallmouth,” “Dissent,” and “Gospel”—Santa Tarantula guides readers on a journey of healing alongside the speaker’s search for autonomy and self-love. In the collection’s opening poem, “Smallmouth,” Pérez asserts that what is left unsaid “demands to be / known.” This becomes the central motif of Santa Tarantula, urging readers to confront uncomfortable realities. Pérez’s award-winning poem “Deadgirl” does this brilliantly through the speaker’s observation of how a brown mushroom sprouting from the soil looks like the knee of a dead girl. The rain comes and mushrooms sprout everywhere, impossible to ignore, but eventually, the mushrooms disintegrate back into the earth. Indeed, the dark underbelly haunting this collection is the way violence committed against girls is suppressed. The speaker is left with lingering silence and feels dangerously unsafe in her own girlhood, “the [same] way [she] couldn’t be sure / which house in the neighborhood held the man // who touched little girls, and so in every house / is the man who touches little girls.” The omnipresence of femicide and sexual abuse is spine-chilling and heartbreaking, yet real—this tangled web of suppressed cultural and generational trauma is the reality Pérez “demands to be / known.”

With these wounds left unhealed, the collection moves into Part II: Dissent. Women align themselves with hissing tarantulas as they warp an ode to a Cuban government that sends dissidents and marginalized citizens to work camps. Biblical women start finding ways to escape their objectified existence as fruit, “swell[ed] with sugar, / [resting] heavy in [the] unloved palms” of their God. Women starve, left empty not only due to lack of food, but by the lack of justice. However, a woman’s desire to quell her hunger does not come without consequence; in “Santa Tarantula,” women ally themselves with the tarantula once again, and both are exalted to sainthood: “Praise / the tarantula woman still alive at forty.” But sainthood rarely comes with respect during one’s lifetime: the speaker swiftly shifts from praising tarantulas to a bone-chilling directive for men who long to domesticate them: “This is how you kill a tarantula. / Cover her, and hope to God she suffocates.” Reading this line for the first time felt like a punch to the gut, and a painful reminder that women are always in danger. However, Pérez leaves a glimmer of hope in the final line: if the tarantula survives, its assailant will face consequences. Still, the speaker persists, and the final poems in this section consider different ways women successfully voice their dissent, like taking communion with open eyes.

This hope bleed into the collection’s final section, Gospel. In addition to extending the Biblical allusions, the word “gospel” urges us to think about what truths need to be shared, or even worshipped. Though an undercurrent of danger remains bubbling beneath the surface of this section, the poems overall are lighter in tone, carrying the radical power of healing, love, and freedom. In “Asymptote,” the speaker’s mother reminds her that the body is a temple, but all the speaker can think of is when “a man / is burning [a temple] in the news.” Despite this, when a man asks the speaker how she can be touched after everything she’s been through, she poignantly asserts, “I refuse / to die having not been pressed to someone / else’s heart, having not come into the fullness of myself, / having not said this is my blood. This, my body. Saying no / or yes, and liking it.” Pérez’s masterful use of enjambment in this section amplifies the speaker’s longing for autonomy: whether she refuses or accepts to be touched, the choice is hers, and hers alone.

The speaker also finds power in herself in the ghazal “I Was Named for the River of Blessings.” The ghazal, a musical form that often contemplates love, spirituality, and loss, is one of my favorite forms of poetry. Pérez chooses the words “halleluiah” and variations of the word “name” as refrains to contemplate the speaker’s origin, struggles with gendered violence, and desire to sing hymns of her female loved ones. The last couplet of a ghazal typically includes a name, usually that of the poet. Instead of explicitly providing a name, Pérez links the speaker’s growth to the Jordan River—a symbol of freedom to the Israelites escaping slavery in Egypt, and the site of many Biblical miracles and baptisms: “Bigger than I am, he touches each growing blackberry, naming / even the greenest ones. Oh, river of blessings. Oh, halleluiah, halleluiah.” These lines gorgeously portray the pure joy of healing, as the speaker experiences a symbolic baptism and flourishing rebirth.

There is much more to write about Pérez’s incredible debut, like her precise execution of form, including a subversive mixed-up sestina, a haunting reverse diminishing verse, poignant prose poems; her feminist reinterpretation of Biblical stories; and her recurring references to insect and reptilian eggs to represent the simultaneous fragility and regenerative power of womanhood. My only wish is that there were more poems in this collection exploring how the legacy of Cuban labor camps lives on in survivors, or that the poems already exploring this were more seamlessly woven into the collection. As with any themed collection, many poems explored the same motif using different forms and language, so it’s natural for the lasting impression to feel like a blended collage. Because Pérez compellingly links predominant narratives (such as those from the Bible) to the intimate struggles of women, I found myself longing for the specter of cultural trauma to linger more in my final impression of Santa Tarantula. Poems like “Mixed-Up Sestina,” “O God of Cuba,” and “Dissent,” which explore the haunting impact of an unjust government on its subjects, were some of Perez’s strongest, adding more nuance to Santa Tarantula’s project to weave a web between historical and personal traumas.

Overall, what most impressed me about Santa Tarantula is its unflinching honesty and urgency to shake its readers out of complacency. It’s a collection that not only conveys the importance of looking at the dark history humanity pushes into the shadows, but also compels us to imagine possibilities for rebirth that are grounded in radical compassion. I am surprised that Santa Tarantula is Pérez’s debut; her poetic finesse, unique use of language, and thought-provoking metaphors make this debut a poignant and unforgettable exploration of societal injustices and the resilience required to overcome them. I will never forget these poems, and I am so excited to follow Pérez’s career as a poet.