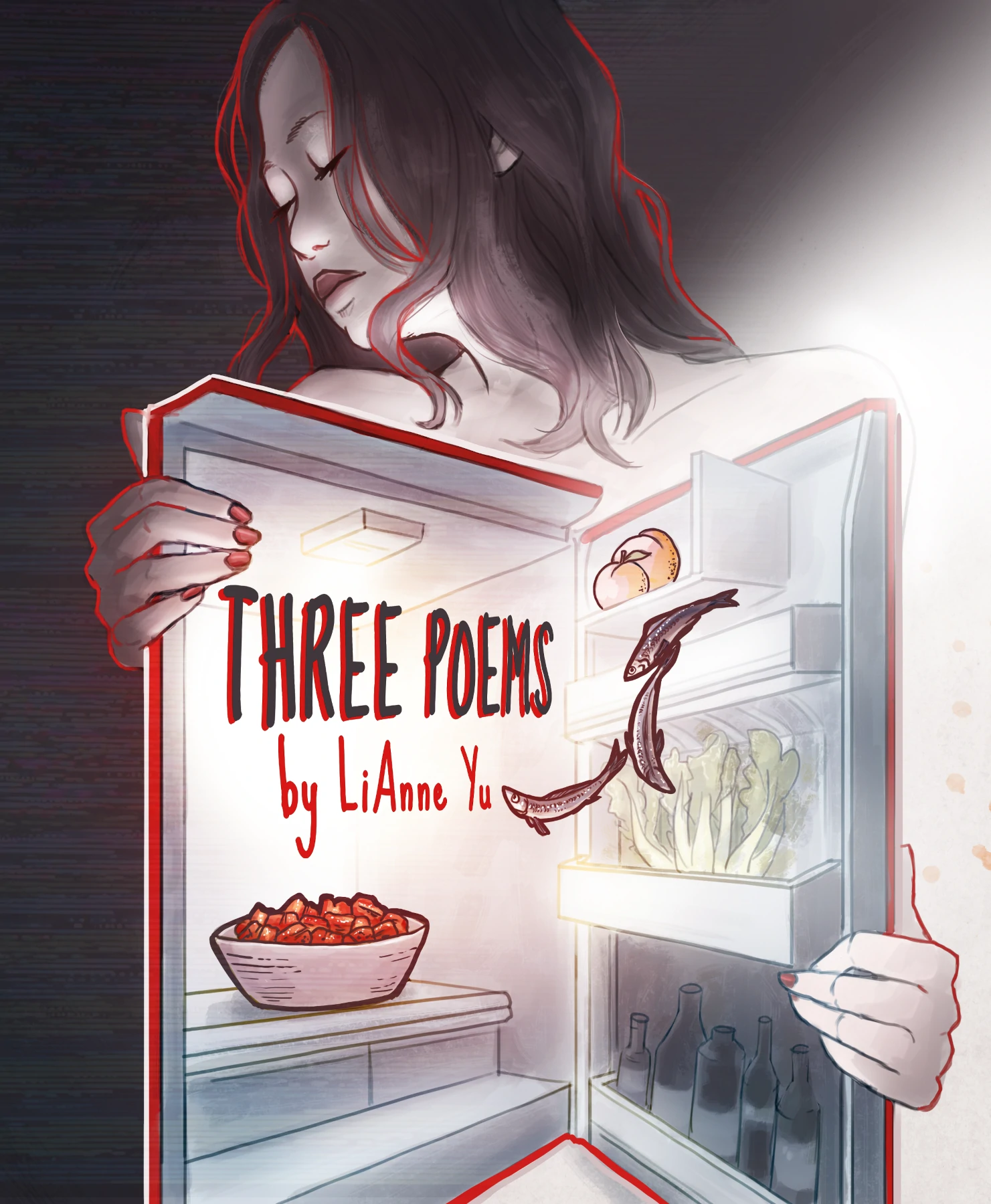

Healthy

Just outside of Chinatown, the stylist holds my hair in his hands and calls to his assistant. “Help me!”

She runs over and sticks her fingers into the dye-free floppy strands.

“It’s hard to hold!” he exclaims. “It’s so healthy!” she nods.

“It is sooo healthy!” he returns.

“We never see hair this healthy,” the assistant speaks into the now-falling tresses I see reflected in the mirror.

I adjust the gold-wire glasses I had to wear today because my puffy eyes would not accept contacts. And all I can think, in this moment, is that at least some part me is healthy as I feel my precancerous cervix cramp.