Kitchen Table MFA: An Interview with Marty McConnell

This interview is part of the Kitchen Table MFA, a series that showcases writing communities through interviews and creative writing.

Marty McConnell’s Gathering Voices is based on her many years of experience facilitating community writing workshops in New York and Chicago. Each of the 24 workshop plans are included in the book.

The writing exercises are innovative – and just fun! Many of them are collaborative, with participants asked to contribute to worksheets that are passed around, so that each writer has a sheet of unexpected words to draw on for inspiration in their writing.

Marty’s emphasis on patience in reading reminds me of one of the most important lessons I learned in my time as a writer in the Inprint Teachers as Writers Workshops. In my college creative writing classes I’d been very taken with my own seriousness as a writer, and one of the things that meant for me was that I spent some portion of each semester trying to figure out who else was serious, who else was good, who I was going to listen to – and then tuning out many of the other students. I can see now how that attitude was born out of both competitiveness and anxiety, and how it impeded my own ability to listen and learn. In those community workshops, however, I wrote alongside writers from a much wider range of backgrounds, and the workshops were led by writers who insisted we take everyone’s work seriously. I remember one early workshop when a participant – a very nice woman, but someone I’d decided was not serious – brought in a brief and, to my mind, straightforward poem. I wanted to jump right to the part where we fixed it – but the facilitator insisted we spend time understanding it first, that we talk about the choices the writer had made with words and images and line breaks. That slowness was hard for me to learn, but it’s an invaluable lesson.

Nancy Reddy (NR)

I really love the workshop plans in your book. They do such a great job of preparing writers for conversation about the selected poem, then using the poem as a jumping-off point for new writing. And I particularly love the exercises that involve collaboration, like the exercise accompanying Ocean Vuong’s “Because It’s Summer” in which students write on slips of paper, then swap papers, and the one for Patricia Smith’s “A Colored Girl Will Slice You If You Talk Wrong About Motown,” in which students trade random nouns and adjectives. They feel like a really great way to interject surprise and play in a writing practice. How did you develop your approach to workshop?

Marty McConnell (MMC)

Before I went to grad school, my only experience with writing workshop was a group of women who got together each week to read and discuss our poems. We didn’t really know what we were doing, but we loved poetry and we loved each other, and it was fun. I loved my MFA workshops and craft classes, largely because I was just absolutely obsessed with language and so grateful to be in a place with other folks who were as well. I also had teachers who, for the most part, were about open-ended exploration of poetry and its possibilities, were committed to supporting us in deepening and broadening our understanding of poetry so that we could sound more like ourselves, rather than conforming to some stultifying idea of what poetry should be. Does that make sense? I felt very freed by what I was reading and learning, rather than feeling like the more I learned, the more I had to fit into some kind of poetry box, which I know is an experience some folks have had with writing programs.

All that to say, when I returned to Chicago I was really interested in doing workshops that incorporated craft conversation, generation of new work, and some feedback opportunities. It does seem that one of the most significant things that sets the Gathering Voices approach apart is the playfulness of the writing prompts. Some of that came from a desire to break out of my own comfort zone, to generate work that did something new or different from what I’d gotten accustomed to creating. I was tired of my poems all sounding the same, and hearing poems from other people that all sounded more or less the same, so we started using these prompts that shake things up. It’s really easy to get attached to the first words we put on the page, for the first thing we make to become super precious, and these workshop practices defy that, complicate that.

There’s also a kind of generosity that gets going when you give away your language, even if it’s just a few words, and that generosity generates its own momentum, and that momentum sparks a kind of connection, a sense of community, among the people in a room making poems together.

Play is essential to writing – if we lose the ability to surprise ourselves in the writing process, we’re never going to produce something with the ability to surprise anyone else. I believe that these group exploratory practices help build that delight muscle, that freeing sense that the more we let go and get our egos out of the way as we write, the more likely we are to connect with the larger source from which great writing comes. And that’s such a joy.

NR

I’m interested in the differences between academic and community writing spaces – the pedagogy of each, as well as how those spaces welcome (or don’t) different identities and different approaches to writing. You have an MFA, and you have a lot of experience as the facilitator of your Gathering Voices workshops. I’m curious how your experiences as a student in an academic poetry context influenced your approach to the community workshop.

MMC

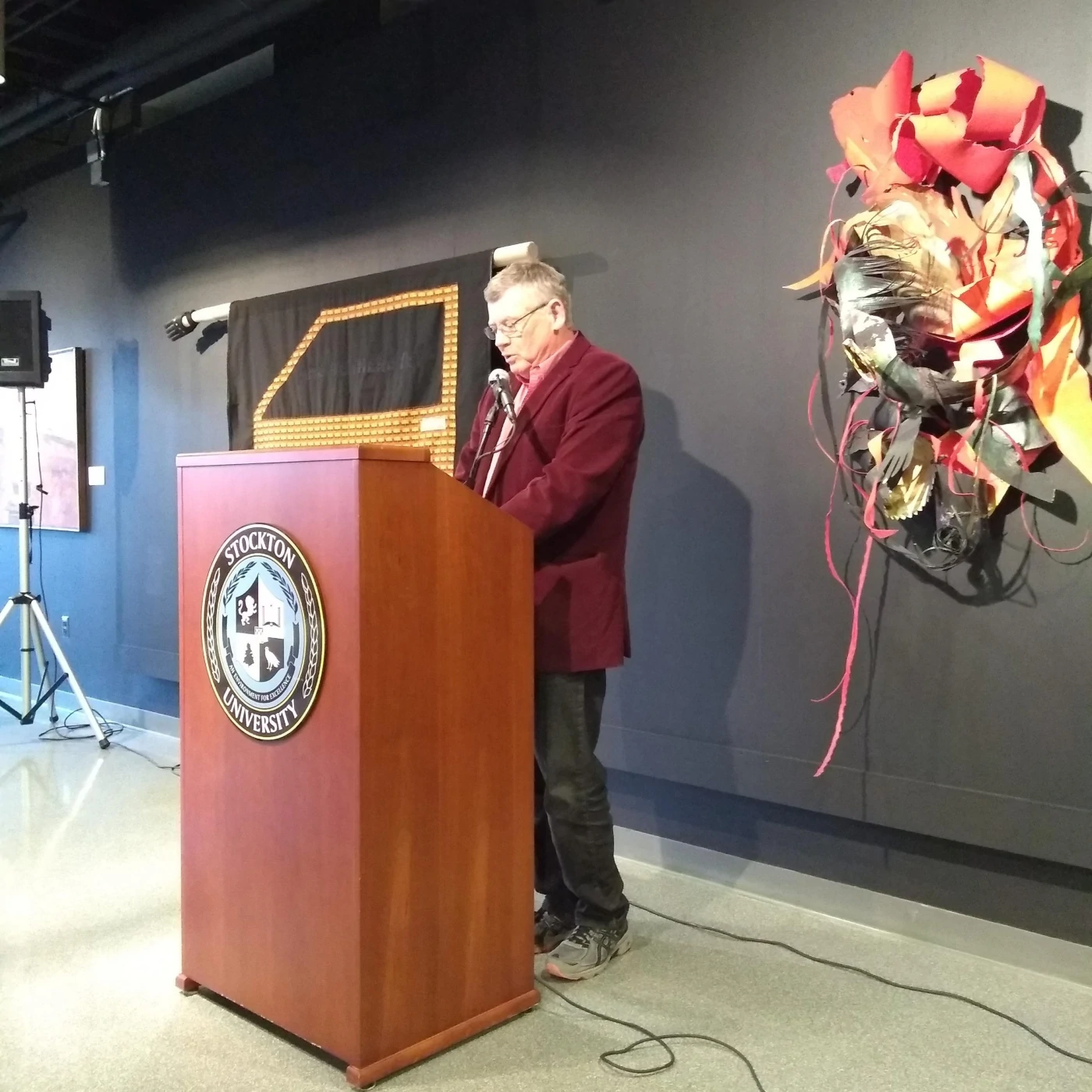

So I mentioned this above, that I really enjoyed my MFA program. I think sometimes about doing another MFA because I miss that sweet rigor. I was so uneducated in the ways of academia, and so in love with poetry, and so fortunate to have simultaneous community in my academic program AND in the slam world… one thing I took away from my academic studies was the need to read broadly and deeply and thoughtfully. Most of the writing workshops I encountered or knew of outside of academia focused exclusively on offering critique of one another’s poems, and while that has real value, it never felt quite enough. My first craft class teacher, Robert Danberg, introduced to us the idea that a poem is a human-made thing, and as such, a thing that can be unpacked to understand its making. Simple. And incredibly complex. And that stuck with me, and really formed the basis for how I approach poems on my own and as a facilitator.

NR

How does your work in facilitating community-based workshops shape your own writing practice?

MMC

I can be a bit of a hermit in my writing practice, and facilitating workshops helps to combat that… while I do need solitude to write, it’s boring only to hear what the voices inside my own head have to say about poetry and the world, and poetry in the world. I’m consistently surprised by what I learn in these workshops, by the ways that others perceive poems and the fabulous tangents and rabbit holes we get to investigate. Each session becomes its own little temporary world, with its miniature obsessions and repetitions – what I take away from sessions is sometimes content, some concept we’ve chased down together, but more often is a reminder that the act of exploring ideas and perceptions without a limiting end-goal (like a test or grade) is as important to the writing process as putting words on the page. I’m reminded that my job as a writer is not to have all the answers, or any answer, but to live into the questions.

NR

Your book is such an incredible resource for people looking to create a community-based workshop, or for writers groups who would like some additional guidance or inspiration. What advice would you give to writers looking to find or build writing community?

MMC

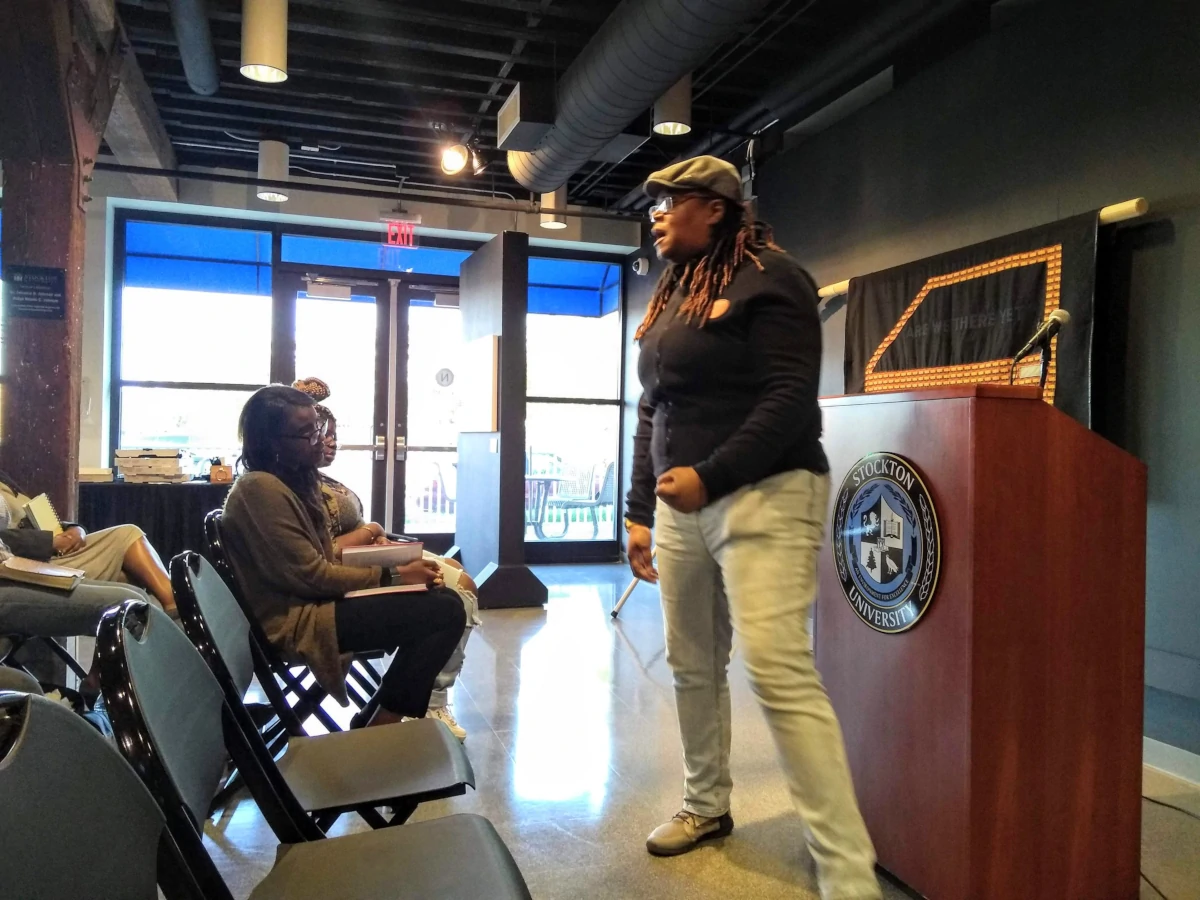

Thank you! My first piece of advice is not to be afraid to start small. A writing community doesn’t have to be large in order to be powerful. Find the folks you connect with, who are interested in some of the same questions you’re interested in asking, and build with those people. Also, go where the people are – open mics, literary events, and such – and let people know what you’re doing in terms of offering workshops. Go places where people who are unlike you in some way gather — pay attention, listen, and talk to folks to see if what you’re offering is of interest, or how you can collaborate.

Looking for more Kitchen Table MFA interviews? Read about Dogfish, ALL, World Above, and Madwomen.