A Review of A Tide Should Be Able to Rise Despite Its Moon by Jessica Bell

When I first received my copy of A Tide Should Be Able to Rise Despite Its Moon by Jessica Bell, I was taken aback by its lightness—its thin pages, unadorned vocabulary, occasional playfulness, and digestible plethora of one-page poems. Despite that, Bell packs so much feeling, admission, and sincerity in the conciseness of this collection without dancing around the messages she desires to communicate. Threading motherhood and everyday life with the string of struggle on a personal and larger level, the character of the boy becomes central, often directly modeled after Bell’s own son, who inspired her to write this assemblage of poetry, her first in almost a decade. As the boy becomes the mother’s world, so too, does the larger world fluctuate to introduce moments of uncertainty and reflection that pervade this collection of untitled poems.

That intersection of boy and world emerges from the very beginning. The first poem opens with a peaceful image of nature as a one-line stanza: “A breath of earth hides in shallow water.” But then, the breath can’t hide for long, as Bell writes in the following stanza, “A small boy disrupts its peace as he plucks it / from its bed of black sand / to use as a skipping stone.” Already the boy acts as a force of change. As the skipping stone skids across the body of water, the presence of the mother and father introduces itself later in the poem, but not in the physical sense. In fact, Bell writes, “It lands next to a shell / that shimmers with the dreams / of the boy’s mother and father. // They dreamed he would live in the colours / of a rainbow, and smile. // The boy looks up. // The clouds part.” The connection between boy and world and an accompanying shift reappears in the clouds’ response, but in this final moment of innocence, the uncertainty of the dreams sunken in the water (though it shimmers) lasts beyond the end of the poem. This poem sets up the rest of the book well by encompassing what Bell seeks to explore: the seemingly small, in-between moments of life that hold in their gravity the uprooting of change and the lessons that follow.

Take, for example, the poem on page 30, a poem where the boy is not present, but his attitude and perspective are. Bell begins by writing, “Yucca leaf shadows / spread like fingers / across the balcony. // They yearn for sunshine / and stretch their limbs / toward the scorching light.” With the personification of the yucca leaf shadows, a sense of childlike curiosity exists in the way they grow on the balcony and tend toward the light. Bell eventually establishes tension in the second half of the poem when she writes, “In summer the balcony drowns in shadows, / but not human ones. / In winter it longs to be stroked again, / with their feather-like souls. // Sometimes, / I try to cast mine. // But the trees seem confused, / and the dragon flowers hide.” The speaker shows the same attitude of curiosity when she, too, seeks to cast her shadow as if it were a game, almost a tug-of-war with the yucca leaf shadows. This game, however, fades away due to a lesson remembered in the last stanza: “Humans and nature / are not great collaborators.” Such is an example of how Bell sustains the voice of experience amidst change.

For poems like the aforementioned, risk abounds in the absence of the son, and the poem may feel disconnected from the rest of the collection. Even with the noticeable, sporadic detachment of a select few poems (like one that focuses on writing after drinking red wine), vulnerability blankets each piece. Bell achieves this through simple, clear language that spotlights her reflections and emotions. The potency of this vulnerability and the structure of some of the poems contribute to the feeling that we readers embody the role of a close friend. The simplicity and clarity of the language never wavers, which left me wondering about missed opportunities for experimentation with more complex language and sentence structures to mirror the intricate reflections lying underneath the surface of each moment. This language, then, can lean toward being too safe, familiar—even occasionally cliché—but this simultaneously nurtures the vulnerability and the reality of motherhood and sheer humanity that is the backbone of Bell and this book. After all, who can deny the love evident in the following lines of the poem on page 49: “He turns to face the window, / pressing his cheek / to my breast. / His baby smell a memory. / Or perhaps…not just yet.”

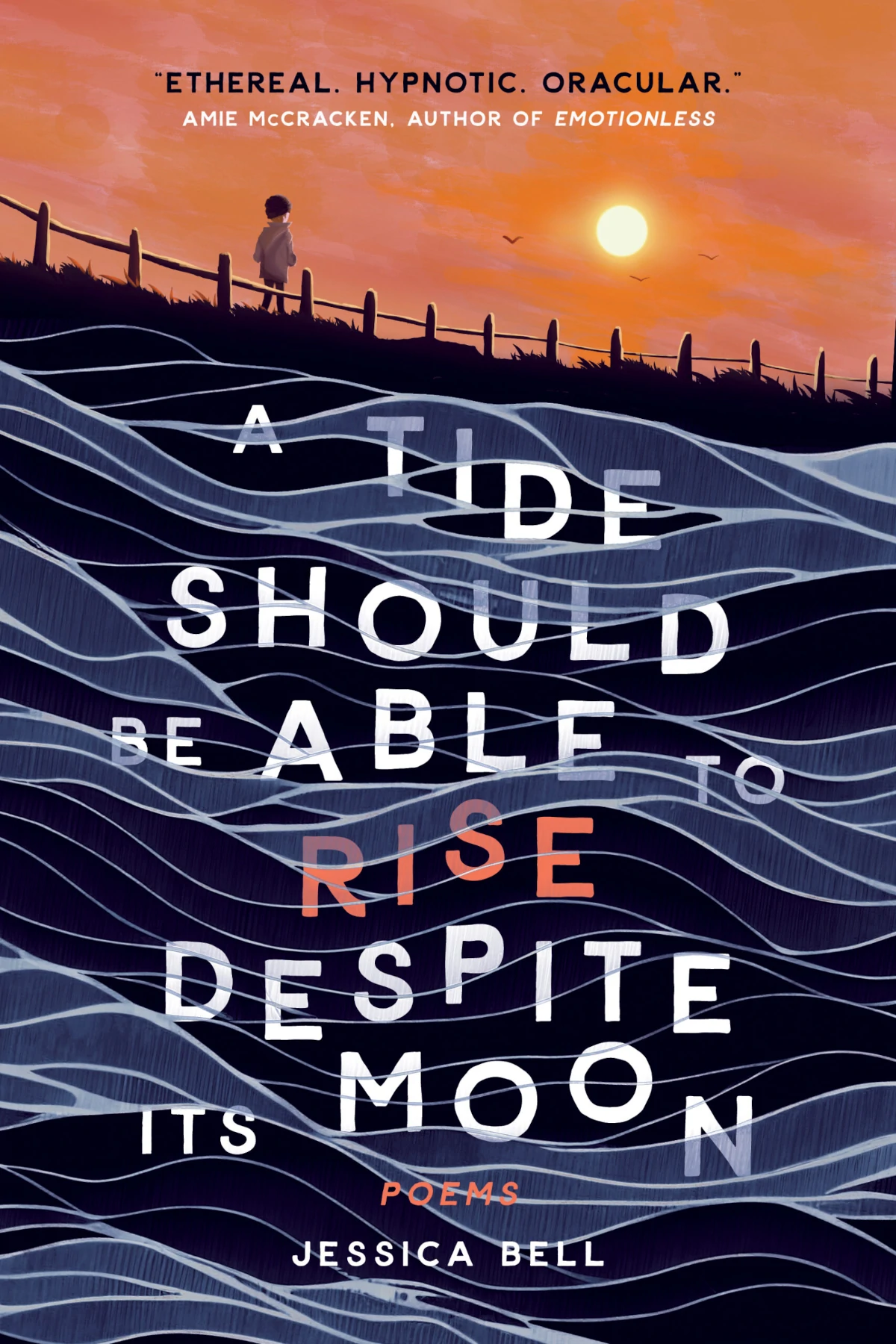

A Tide Should Be Able to Rise Despite Its Moon fully displays a mother’s honest love as it contends with her growing son, a changing world, and her shifting attitudes and beliefs. While the language left me wanting, this collection of poems still proves resonant in its weaving of themes and emotions, which brings me to a reflection on the book’s front cover. The boy, the sun, and the tidal waves are not as separate as I initially thought. All three rise and fall in one way or another, and they keep doing so as time passes, highlighting a type of change that is more patient, alluding to the little moments that build this change. In the poem on page 41, Bell understands this fact when she writes, “How long does it take / to live in the moment? // One second.” The following question might be, “Do we ourselves understand this?”