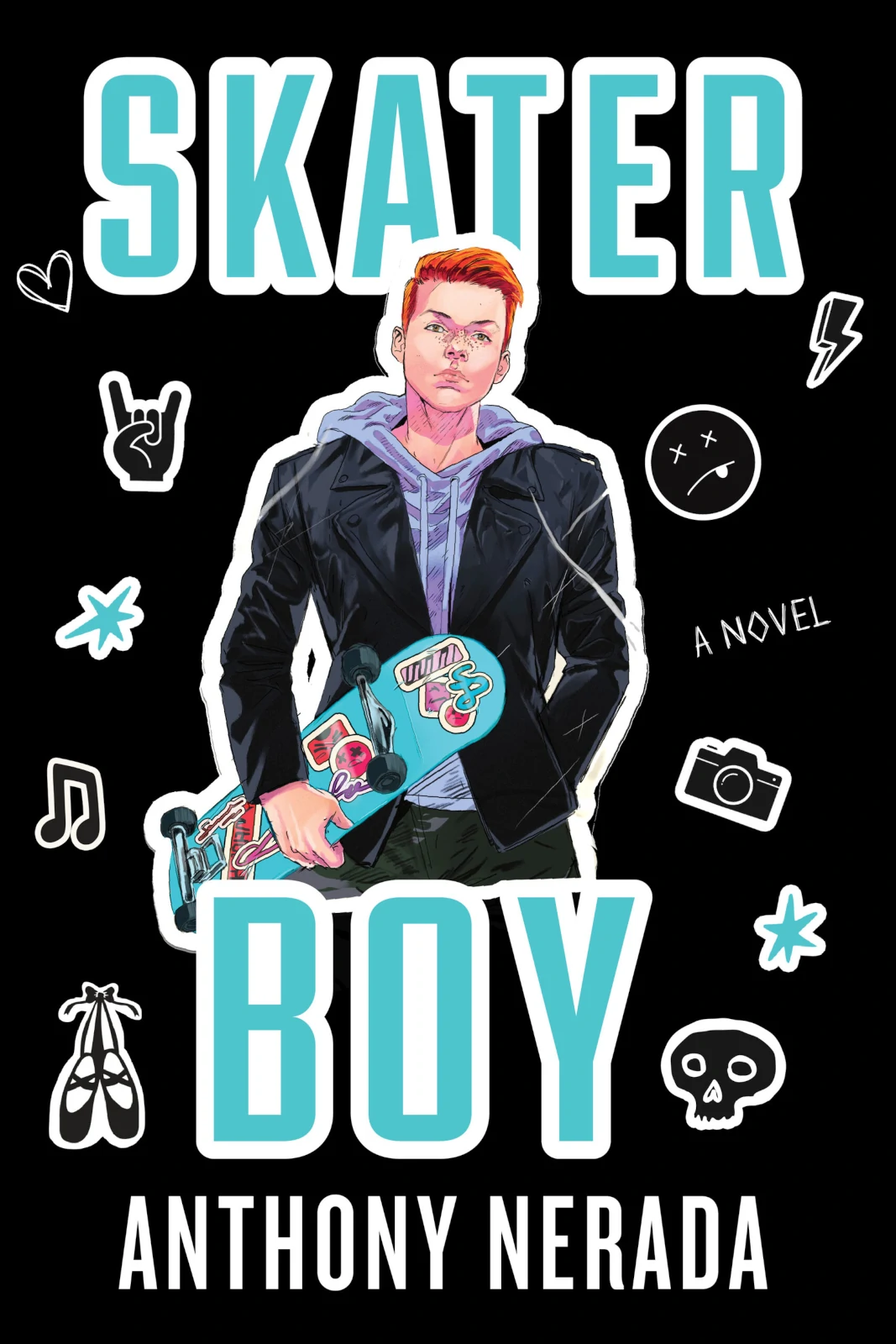

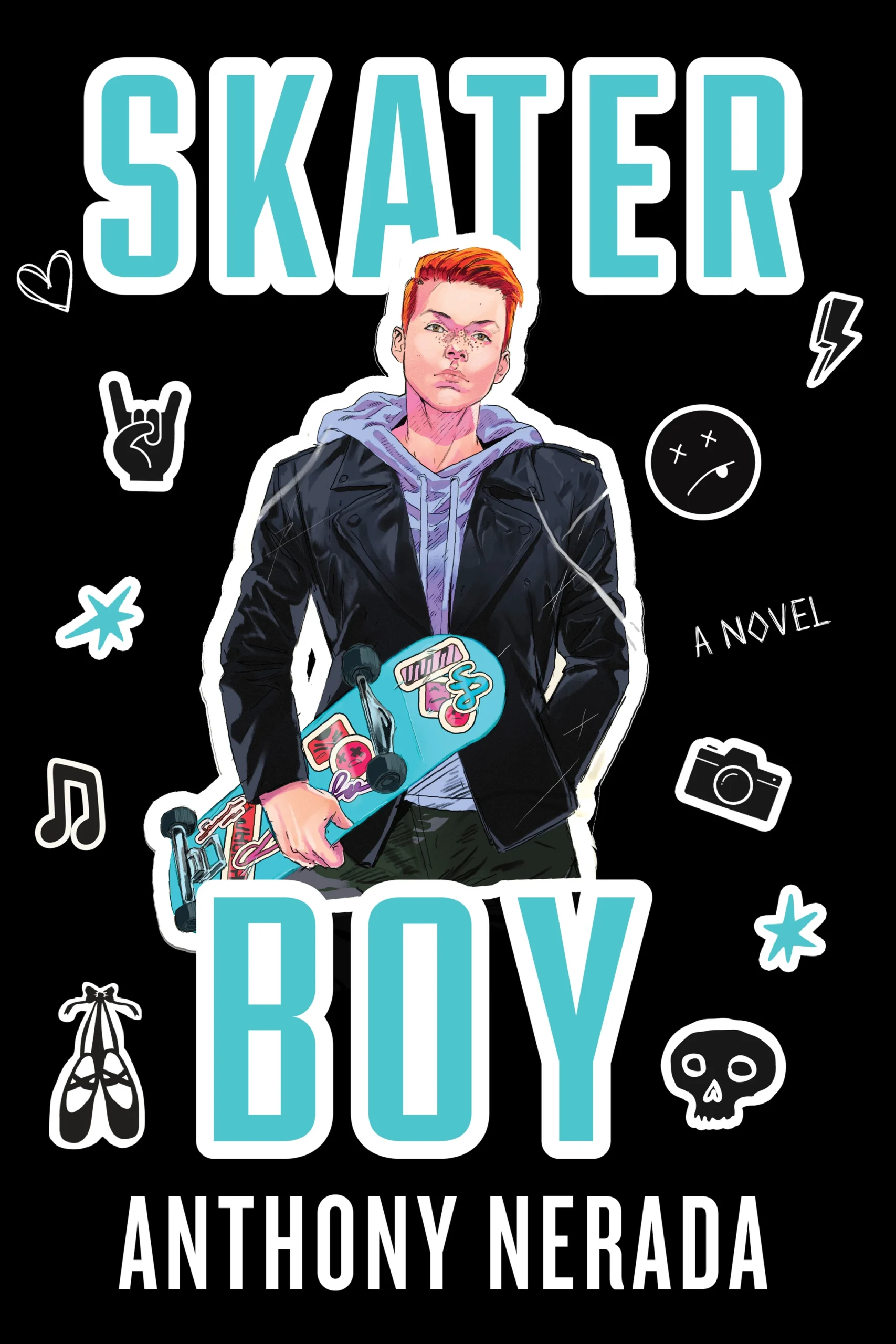

A Review of Skater Boy by Anthony Nerada

*SPOILER ALERT *This review contains plot details of Skater Boy.

Skater Boy by Anthony Nerada was published on February 6, 2024 by Penguin Random House/Soho Teen.

It isn’t easy being your high school’s “resident bad boy.” But you know what’s harder? Being handed that title without wanting it in the first place. Skater Boy by Anthony Nerada centers around Wesley “Big Mac” Mackenzie, who isn’t what you’d call a model student. He’s skipping class, stealing lunch, and getting into fights, because that’s how the universe sees him, so that might as well be who he is, right? Teachers and other students don’t see him as someone trying to provide for his family or someone struggling with anxiety and trauma. That is, until Wes meets Tristan, the beautiful ballet dancer, after being forced to see The Nutcracker, and realizes what he wants might not be what he currently has.

Wes is a very real, awkward character. There were times he had me smacking my hand against my forehead. Hard. Thanks to teenage boy defense mechanisms and intentionally stunted dialogue, Wes’s and Tristan’s first interaction gave me secondhand embarrassment that made me want to bury myself alive. And Wes’s thoughts, sentiments, and actions mimicked those uncomfortable feelings throughout the book. That’s the beauty of seeing things through his eyes, though. He isn’t perfect, and he lives up to his age by making silly mistakes without understanding how to fix them. Wes felt like a testament for anyone that as long as they keep pushing, things will end up okay.

There are readers who will see themselves in Wes. And, when it comes to characters in media, whether that be in television, articles, or books, representation is important. The alleged failure, the gay kid with no future. They’ll see it’s okay to not understand where they are in their lives. There are also people who will see themselves in Tristan. The gay, black ballerina who loves what he does. And at first, maybe they’ll blink because, “Black guys are supposed to play basketball, right?”

That representation extends to highlight the ways Wes was failed in Skater Boy. A failure I’ve seen first-hand. Society has and continues to fail children, because yes, teenagers are children, who need patience, understanding, and guidance. Instead, they get belittled and told they aren’t good enough. They can’t get into a certain school, because have they seen their grades? They’re not going to graduate on time, because have they seen their track record? They aren’t going to amount to anything in life, because, well…look at them. This is the exact situation Wes faces as we’re welcomed into his story. His guidance counselor breaks the news that he won’t be graduating, and rather than encouraging him, he discourages Wes by saying, “You’ll never be a lawyer, not with those grades.” At first, Wes doesn’t care as he doesn’t believe college is the end-all-be-all. But then he discovers what he really wants to do—photography—and starts working hard to get his grades up to achieve his dreams, despite the lack of encouragement.

Nerada explores other important topics throughout Skater Boy, too. In one scene, Wes follows Tristan to practice after dropping a ballet slipper. Tristan freaks out, ready to attack. Wes apologizes but doesn’t understand why he’s so upset. Then, he notices the Black Lives Matter sticker on Tristan’s bag and realizes how terrifying the situation must have been. Incorporating social movements in media will always be important because they’ll never go away. The self-awareness shown by Wes is needed and appreciated in this novel—especially since he takes the situation as an experience to learn from.

Without going into detail, there’s a point in Skater Boy where Wes loses sight of himself and starts to push away those he loves. While that choice frustrated me, I understood. Even though things start to improve in his life, his emotional problems don’t disappear. Wes changes, but it’s slow. And it’s certainly not every part of him at once. He’s a teenager who’s been through a lot, and a few weeks of happiness with Tristan isn’t going to miraculously fix that. A kiss isn’t going to wipe away the trauma, the fear, or the doubt bubbling up inside of him. And I am glad it doesn’t. It only makes Wes’s character that much more human and relatable.

The relationships portrayed throughout Skater Boy further emphasis the nuances of Wes’s world. Nerada explores an array of connections that expand as the story unfolds. There are relationships between Wes and Tristan, his best friends, his single mother, a future stepfather, and even past victims of his bullying. As someone who lives and breathes well-developed, meaningful side characters, I was ecstatic about everything they offered in the novel. Almost every character pushed Wes to become the best possible version of himself. His former bully victims, for example, showed him there is redemption if you’re willing to try.

With that said, there are a few side characters I wish had more light on them—a great example being Hannah, Wes’s future stepsister. Wes’s seemingly positive relationship with Hannah was a great foil to his negative feelings about Tad, Hannah’s father. Wes pretends Tad doesn’t exist, but he’s gentle with Hannah. He tickles her, tosses her over his shoulder, and gives her candy when he could have ignored her. We only get a couple of moments between Wes and Hannah but giving them more time together would be an opportunity for Wes to explore, in depth, why he felt comfortable with Tad’s daughter but not Tad himself. Is it because she’s young, because he likes the idea of having a sibling, or is there something else left unsaid? This rings true for other side characters, too, such as Tristan’s best friend, Emily. By the end of the story, I felt I still didn’t know who some of these characters were outside of them knowing Wes. Expanding upon these characters would give Wes (and readers) a better chance at understanding him and his actions, how they affect those around him, and how those around Wes affect him in return.

Skater Boy is an amazing debut novel about a boy who learns what it means to rip off labels and be himself. But this is not only a story teenagers deserve to read—it’s a story that needed to be told. A story about what it means to to be young and queer in a world where adults may fail you. A story about taking the first steps to overcome the struggles one might be facing. A story about how you owe no one, but yourself, the life you want to live.

For more information on Anthony Nerada, check out this interview!