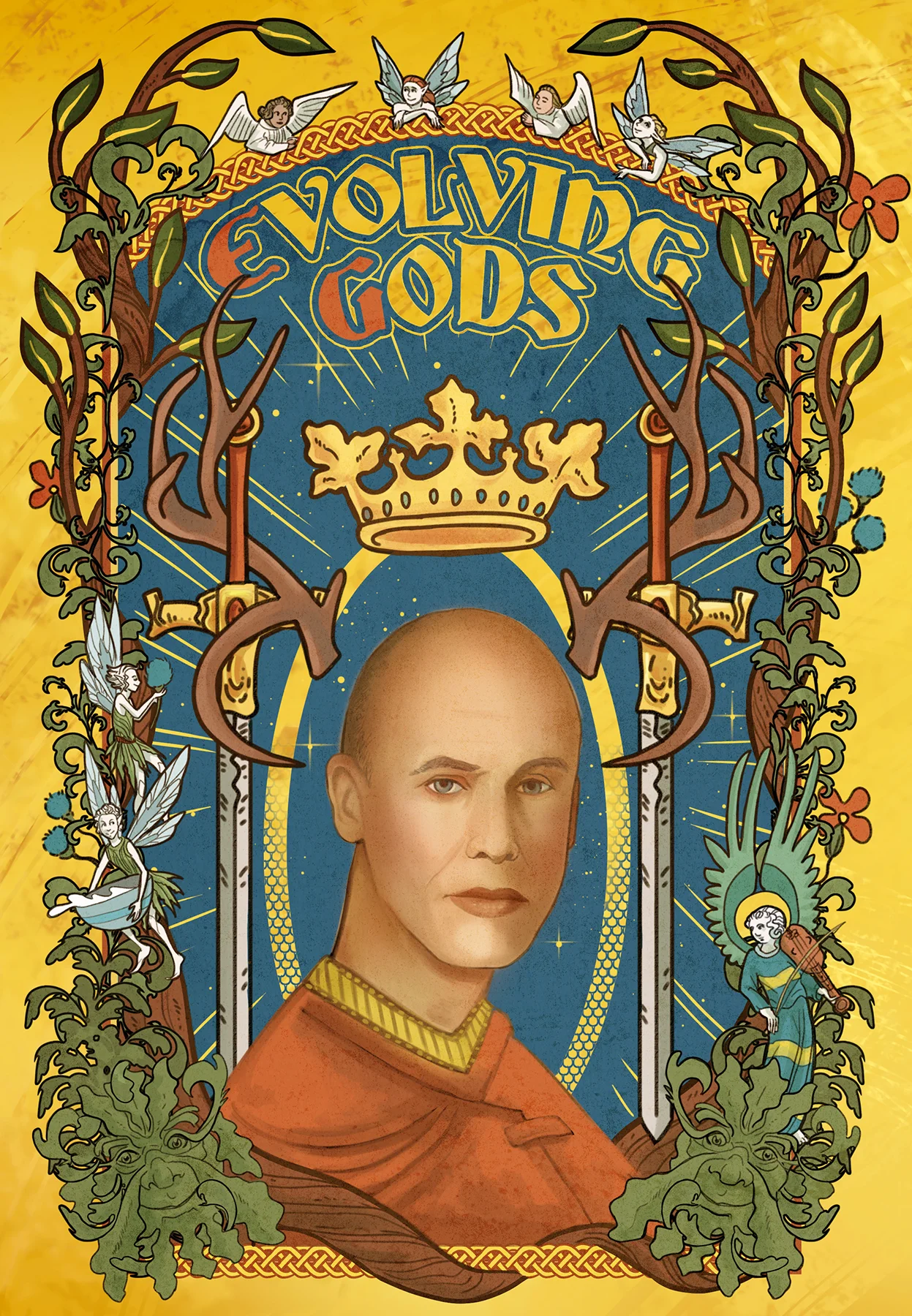

The Bartender and the Panther

The knell at the door tolls.

I turn. A black paw swipes mercilessly at my face—claws sharp, bloody, and vicious. I snap my fingers. He freezes mid-snarl. I hum indifferently.

He is sleek, his coat gleaming under the club’s cold neon. This panther will drink Death in the Afternoon.

“Welcome to the Nightclub for the Newly Departed,” I say. “Denial, yearning, and violence are not permitted here.” I nod to one of the many signs plastered around the club:

RULES—Once you step into the premises . . . “What will you have today?”

It’s a meaningless, ritualistic question; I’m already retrieving a coupe glass. The panther drops to his haunches, growling. His eyes are the color of a split lime.

Perfect, I muse as I work. The right absinthe, topped with champagne, creates a heavy cocktail as green as his gaze.

“You look like one of them.” He hisses.

Lemon twist on the rim. I slide the coupe glass over to him and press my fingers together. Snap,and the glass is replaced with a broad glass dish. “I was born millennia before your poachers. I did not know them.”

“Why did they kill me?”

Arrogance. Money. Boredom. Desperation. “Drink,” I say. “Be at peace.”

The panther growls. “My life was unfairly ripped from me. Peace?”

I can see his fury; it coils off him like smoke and hisses like a lit fuse.

Murder victims are all the same. Rage blankets helplessness, but never extinguishes it.

They are not my favorite customers.

“Drink,” I repeat.

“No.”

“What do you want? Revenge?”

His tail lashes. “I want them to burn in the wildfires they set to my home. To feel their own bullets tear through their hearts.”

I spin into the usual rhetoric. “Revenge is a fantasy. We are on an entirely different plane from reality. You will never see them again. Will you let that anger consume you? Drink.”

The panther does not consider my words; his unwavering gaze does not break. “You,” he hisses, prowling the table. “You are worse than them.”

“I told you I never associated with your poachers.”

“No. You. You, with your monotone voice and your indifferent gaze. I would rather see hate, or the pride in my killers’ eyes. Have you spent your millennia holding yourself above the pain of others? Have you been so devoid of life that you have lost your heart?”

My fingers falter on the counter.

“This job calls for no empathy,” I say, after a beat too long. “I serve and endure.”

He studies me, head tilted, tail curling in silent question. Then, finally, he dips his head and laps at the cocktail. The dish is empty in seconds.

“Acceptance,” I say, my voice thinner than I intend. “To drink is to accept.”

The panther looks at me one last time, searching for something I cannot name. Then he leaps off the counter, vanishing into the scattered crowd. I watch him go, tasting absinthe on my tongue.

It is bitter, sharp, and green.