After the Snake

I’m the one who told Jake to leave. I laid hands on him first, have always been the one to lay hands on him, and I know it’s wrong, but I can’t figure out how to get through his beer-haze, how to get him off the couch to do anything, especially to find a job or to make things official between us. I punch or kick or scratch at him when he tries to stare through me at the TV, and usually he brushes my hands away and twists the top off another beer. It doesn’t matter what kind of beer it is, he can always twist the top off. One of his self-proclaimed “special talents.” But this time, he grabs both my wrists in one hand and slaps me hard across the face, so I feel my brain rattle a little and my neck pull. He blames Afghanistan, I know he does. He never outright said it, but after he slapped me, he stood up and put his face next to mine and said, “Casey, you couldn’t possibly understand what I’ve been through. Let me drink my fucking beer.”

“You could’ve hurt me,” I said, shaking my head from side to side to see if it hurts. “If you ever lay hands on me again, Jake Mackmilan, it’s over. Maybe you should even leave right now.” He downed his beer and stood in front of the TV for a moment. It was the only light in the room and it made his skin look almost silver. Then he grabbed his keys off the counter. I heard his Kawasaki rip to life, the one I bought for him. After a minute I went and stood at the front door, playing with the switch for the porch light that doesn’t turn on. When Jake didn’t come out of the woods that surround our house and back up the dirt drive to beg for forgiveness, I collapsed into his chair in front of the TV and watched the nature documentary he’d been so intent on, nature’s natural killers.

When I wake up it’s after midnight, the documentary has switched over to a ghost hunter show, and Jake still isn’t home. I pull out my phone and call him, but the seat of the chair starts buzzing, and I pull his phone out from where it’s wedged between the cushions. I set it on the counter then move to our bedroom and leave the bedside lamp on, so he knows I’m waiting for him. Our room is undecorated. When I moved in, I didn’t want any reminders of the rooms I’d left behind, so I threw out my posters and the sharpie drawings I did of myself, black and warped, the ink bleeding across the page. Jake doesn’t have any decorations, either. Maybe that’s why we fit so well together, because neither of us wants anything to do with our past lives.

Our bed has no headboard, just a cheap metal frame I bought with my second paycheck. I sit propped up against the wall. I don’t let myself consider the possibility that Jake might not come back. He needs me as much as I need him. Maybe more. I tell myself, “I’ll wait up for him,” but I fall asleep anyway, and wake suddenly to Jake standing over me. It takes a second to register that it’s him, his slumped, muscled shoulders and his bristly short hair and his brown eyes, because there are bits of flesh missing all over his long, lean arms, the wounds wet and filled with pus, but not bleeding. I try to say, “Jake!” and reach out to him, but my arms are frozen at my sides. I will myself to sit up, try to say, “Are you hurt?” but I am paralyzed. A familiar panic starts to clutch at my chest, my heart thumping hard. Jake sits down next to me. He leans in toward me, and the flesh on his face disappears. His face is a mask of bone. I see it for only a second before it swoops down out of my sightline, and I feel his lips soft on my forehead. When he pulls away his face is whole again, he’s all whole, except a scrape on his forearm.

I think, “It’s just a dream,” willing myself to control my breathing and my racing heart. I just need to wake up, so I can tell him, if he’s really here, “Hey baby, I’m glad you’re home.” But he backs away from me, favoring one leg over the other like he always has. His brown eyes stay locked on mine until he’s out of my line of vision. For a second I can’t turn my head, then suddenly I can move again, and I look at our bedroom door. It’s empty. My cheeks are wet, but I don’t remember crying. I resist the urge to curl into a ball like I used to do after this would happen when I was little, to huddle beneath my sheets. Instead, I run to the door, calling after him, “Jake! Jake!” I run down the close, short hallway, where the hall light is still on, my feet pounding on the old wood floors. I take the sharp right into the kitchen, scan the semi-darkness of the dining room and the living room, but he’s not there. I grab our heavy silver flashlight and shine it out the front door, into the black expansiveness of our dirt drive and the woods beyond, but his bike is still gone. I shut and bolt the door quickly, then make my way back through the house, systematically flipping the rest of the lights on as I go. I keep half-expecting Jake to jump out at me. It’s just the sort of thing he’d do, to lighten things up after our fight, or maybe to punish me, but he doesn’t. I shine the flashlight into the bathroom, the only room I haven’t checked, then flip on the light in there, too. I jump at my reflection in the mirror over the sink and close the bathroom door behind me. In our room, I lie back down, set the flashlight on the nightstand, and try not to go to sleep.

When I was ten, in the long, loud nights before my parents’ divorce, I fell asleep late one night and woke to a monster breathing above me. He had the body of a man, but with smooth, eerily fluid skin, almost like quicksilver, and no orifices. Where his head should have been was the skull of an antelope, empty eye sockets full of distorted, oozing dark. My arms were pinned to my sides as he first stood above me, then retreated. He scaled the walls of my bedroom and scrambled across the ceiling. He hung above me, his hands and feet sticking to the ceiling, his head rotated 180 degrees to stare down at me. The darkness seeped out of the skull, and as it settled around me like a thick fog, a pair of bloodshot blue eyes blinked within their mask of bone. I tried to open my mouth, and as if I were in a dream, I could not scream, I could not even whimper. I tried to turn on my side and run, but my limbs were completely useless. I was glued to my bed, watching the monster watch me. After a while, it crawled back down the wall, stood over me again, and finally left my room. It was then that I found myself able to sit up and cry. I ran to my parents’ room, where my mother was crying too.

“Go back to bed,” she told me. She was sitting on the edge of hers, wearing one of my father’s T-shirts, her heavy eyeliner smudged and blurred.

“I can’t,” I said, but my father came out of the bathroom and said, “Go to bed,” and I did. I lay down with the lights on, pulled my polka-dotted comforter up to my chin, and kept my eyes shut tight. I focused on the muffled sounds of the bedframe slamming against the wall in the room next door and tried not to fall asleep, afraid the antelope man would return. Once or twice that night I thought I felt a shifting of weight on the bed next to me, thought I heard a slight creaking of bedsprings, as if someone were getting up, or sitting down, or even lying beside me, but I told myself it was my mother, and I didn’t open my eyes.

In those months I would see the antelope man again and again when I was jarred awake by shouting in the next room, and it never got easier to lie there motionless, at his mercy, wondering if that night something would change. Perhaps tonight he’ll come down from the ceiling, I’d think, and steal me away. Or maybe I’ll feel his hands close around my throat, like my mother’s did, once, when my father had been missing for two days, and I wouldn’t stop asking why. I took to trying to fall asleep with the blankets pulled over my head, but inevitably they would slip away. I could not stay still as I tried to sleep through the fights in the next room. No, I could only stay rigid when the monster was standing over me, breathing, waiting.

After the divorce was finalized, I moved in with my grandmother up in North Carolina while my mom “got settled.” Other than the months after I met Jake, that was the best time of my life. Every night before I fell asleep, my grandmother sat with me. I lay on my stomach and she slipped her hand beneath my pajama top to draw pictures on my back with her cool acrylic nails. The antelope man never came to that place. It wasn’t until my grandmother had a stroke and died when I was fourteen that it started again. I nodded off at her wake, which my mother held back in Florida. The lid of the coffin creaked open and my grandmother sat up and stared at me, half of her face slack and drooping. She pulled herself over the edge and hunchbacked her way toward me, the undertaker’s makeup clownish and distorted, the lipstick smudged far past the edges of her mouth, her nails bright red and twice as long as she ever kept them in life. I tried to shout, “She’s not dead!” but again my voice wouldn’t work. I tried to shuffle my chair back, but it was as if someone had screwed it to the ground. One of my aunts let out a wail, and I woke and clutched the sides of the metal folding chair the church had provided us with, and made certain the lid of her coffin was still closed.

When the sun comes through the window in the morning, Jake still hasn’t returned, and I’m exhausted from staying up all night. I call off work at the Publix in town. I can’t go, anyway, without Jake to give me a ride. We sold my car when I moved in and bought the motorcycle we’d seen for sale in someone’s yard. Well, I bought the motorcycle. Jake didn’t like to deal with people more than he had to. Afghanistan, I figure.

I pull on a tank top and a pair of Jake’s basketball shorts, and lace up my hiking boots. I start off down the dirt road toward the highway, following the shallow rut left by Jake’s tires all the way to the main road, which is lined with pastures and quiet at this time of day. I stand for a minute and watch a few trucks whip past. When sweat starts to prickle on my neck, I turn and follow the creek. The low-hanging branches that line the water are dripping with Spanish moss.

When I reach our spot I want to see Jake sitting there, head in hands and eyes red, working up the courage to come back home and apologize to me. He’d say, “I promise things will be different now. Like when we first met. Remember? I’ll be good to you.” But the grass is unbent, almost militarily erect, like no one has been here for a long time. I know I haven’t.

Jake and I met here one day when I was skipping school. I’d been napping in the sun when I opened my eyes and Jake was standing over me. “Don’t move,” he said, “There’s a snake curled up next to ya.” I lay there frozen, staring up at him, trying to keep my breathing shallow so as not to disturb the snake. Jake crouched on his haunches, his brow furrowed. At first I tried not to stare at him, but when I saw that he was keeping his gaze fixed just behind me, I took him in, his broad shoulders, his pale arms in his tank top, the dark tan of his hands and face and neck. After what felt like ten minutes he rose slowly and said, “Maybe I should try to scare it away.”

“No,” I whispered, but he grabbed a stick, leaned over me, and made a shoveling motion. I heard the soft sound of the snake’s body hitting the ground a few feet away, and Jake grabbed my hand and said, “Run.”

He led me through the woods until we came on a clearing where a little brown house sat in the middle. “You want a drink of something?” he said. “Lemonade? Beer?”

“Is this your house?” I said as we walked toward it.

“No,” he said, “I’m taking you to a stranger’s house and we’re going to steal lemonade and beer from their fridge.”

It took me a moment too long to catch the sarcasm, and Jake burst out laughing before I could even smile.

“I’m Casey,” I said, half-inclining my head towards him. “What kind of snake was it?”

“Coral snake,” he said, “Black and yellah and red. Striped.”

I shivered. Jake put his hand on my arm and said, “Don’t be scared. You’re safe.”

He opened the door to his house. The handle hung loose. “Some kids tried to break in,” he said when I asked about it. “I’ll fix it soon.” He led me to the fridge, an old, squat one, beige with a wood-plated handle and veins of dirt on the surface.

“What’s your name, by the way?” I asked.

He leaned into the fridge and didn’t answer me until he’d turned to face me, holding two bottles of beer in his hands. “Jake Mackmilan.”

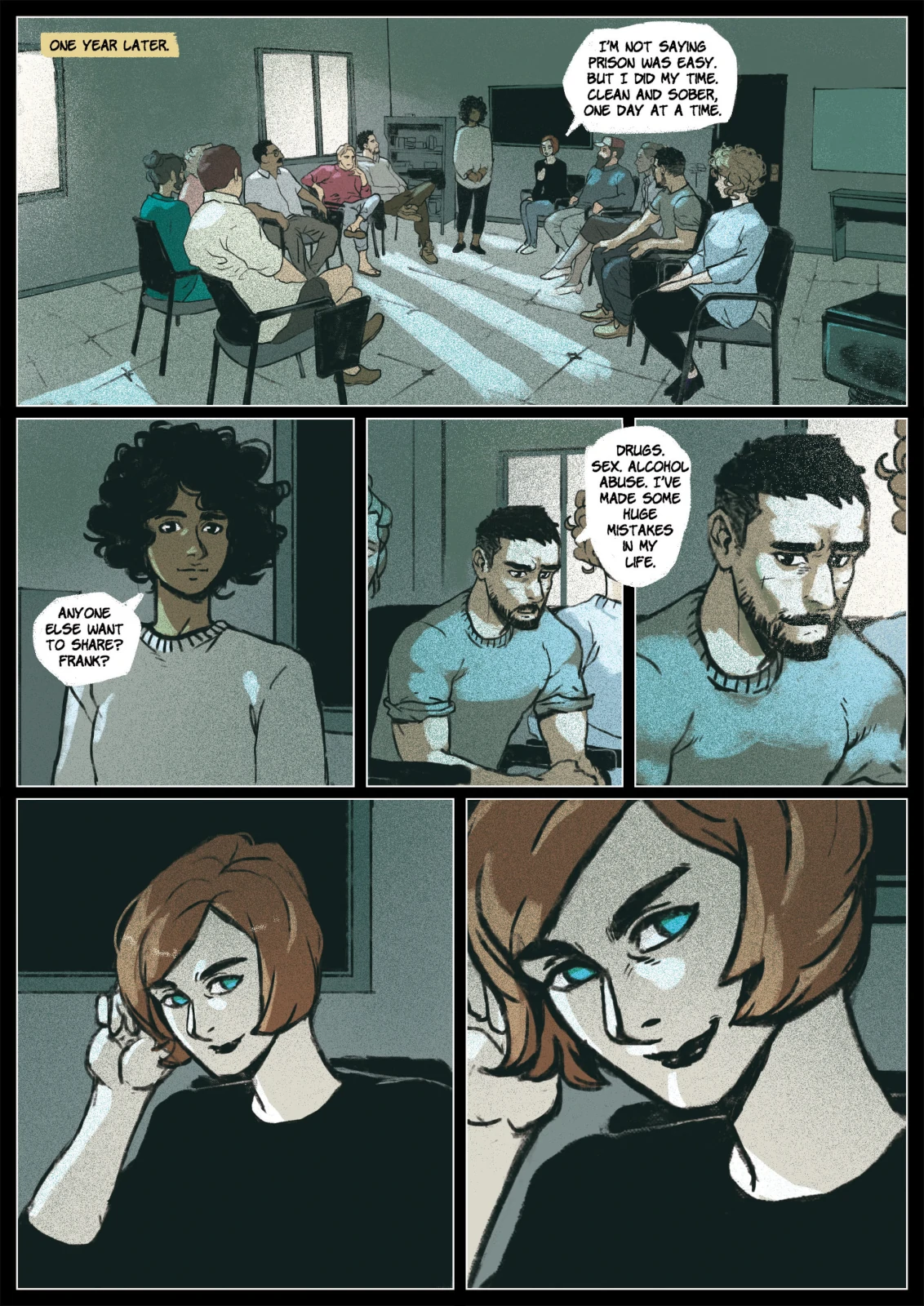

It’s nearly noon, more than twelve hours since Jake left, when I get back to our house. Exhausted, I crawl into bed and try to clear my mind for sleep. The paralysis hasn’t happened since I moved in with Jake over a year ago, and now I’m back in bed I can’t stop thinking about it, that closing-in feeling of not being able to move, of being completely out of control. But I know there’s something more, something bothering me that I can’t put my finger on. I keep trying to breathe through it, in and out, but those first seconds of his appearance last night keep replaying in my head. I give up on stopping the memory and let it run through like a movie. When I get to the feel of his lips on my forehead, my throat tightens, and it’s a few seconds until I realize why. Not once in my years of monsters has one of them ever touched me, but I can remember that feeling clearly, his lips soft and warm, just like they were the first time we had sex. I cried on the mattress on the floor in our little brown house, and Jake held me and pressed his lips to my forehead. That exact same kiss. He said, “You don’t have to tell me why you’re crying, but I promise it’s okay.”

Never has one of them touched me.

I wake to my phone vibrating in the bed beside me. The sun is still coming through the window, and I’m exhausted, but I scramble to answer the phone. I don’t recognize the phone number, and my stomach drops before I remember Jake forgot his phone, anyway. I slide the button and say, “Jake?” hoping he’s found a payphone and is calling to say he’ll be home soon.

“This Casey Compton?” The man on the other end has a North Florida drawl, a lot like Jake’s, but it’s not him.

“Yes,” I say, sitting up in bed.

“This is Officer Daniel Knox, I’m with the police department. Do you have a Kawasaki motorbike in your name under the plate number XJM95?”

“Yessir,” I say, thinking Jake might’ve been pulled over for driving drunk. He never thought he would be, since he only rode at night, through the woods on the back roads that led to our house. If the moon was bright enough, he rode with his lights off. It made him feel alive, he said. “But I don’t actually drive it. My husband can’t deal with people, so I bought the bike for him,” I say. Then, feeling the need to explain further, I add, “He was wounded in Afghanistan. PTSD.”

“Can I come by this afternoon? The address I have for you correct? 1 Hickory Lane?”

“Yessir.” I hang up the phone with a heavy weight in my stomach and get out of bed. I examine myself in the mirror and decide I can’t get away with not taking a shower—my hair is in nests from sitting hunched against the wall for so long, and the sweat from my fear the night before made it greasy.

I wash my hair and soap my pits, using the rose-scented soap Jake loves. My mother used to say, when I lived with her, “A good-smelling girl gets out of trouble.” She was always heavily perfumed when she went out at night.

I wait for the officer on our porch, the part of the house that excited me the most when Jake led me to it after we first met. He’d inherited it from his parents, he said. The porch slopes a little, toward the middle, and I would’ve painted the railing white instead of brown, but it wraps around the whole, tiny house, and the posts are carved in swirling patterns. I’d planned to get a rocking chair, once Jake got a job. I stand, waiting for the officer. He pulls up in a patrol car, dust flying even though he’s moving fairly slowly. When he gets out of the car he looks different than I imagined him, not much older than I am, at least six-foot, blond and clean-shaven with a bold jaw.

He says by way of greeting, “You don’t get scared living out here all alone?”

For a second I want to say, “Yes,” not just because of last night, but because that silly girlish part of me, the part that leapt up when I met Jake, wants him to protect me. Instead, I say, “I live out here with my husband.”

He says, “You want to go inside? I’m afraid I have some bad news.”

For a second I think, “God, he’s killed himself, hasn’t he,” imagining the bike with Jake under it, spun out on a dirt road. Then I remember the lips on my forehead and wonder if Jake was really here last night, or if it was like my grandmother. Maybe he came to say goodbye.

“Ma’am?” Officer Knox is looking at me with a furrowed brow. “I understand if you’re in shock. . . let me help you inside.”

“No,” I say, realizing I never answered him and trying to sound put together. “The porch is the best place for bad news. It’s bright.” I sit down on the steps and pat the porch beside me. He sits down a few feet from me, but his knees wing out so ours are almost touching.

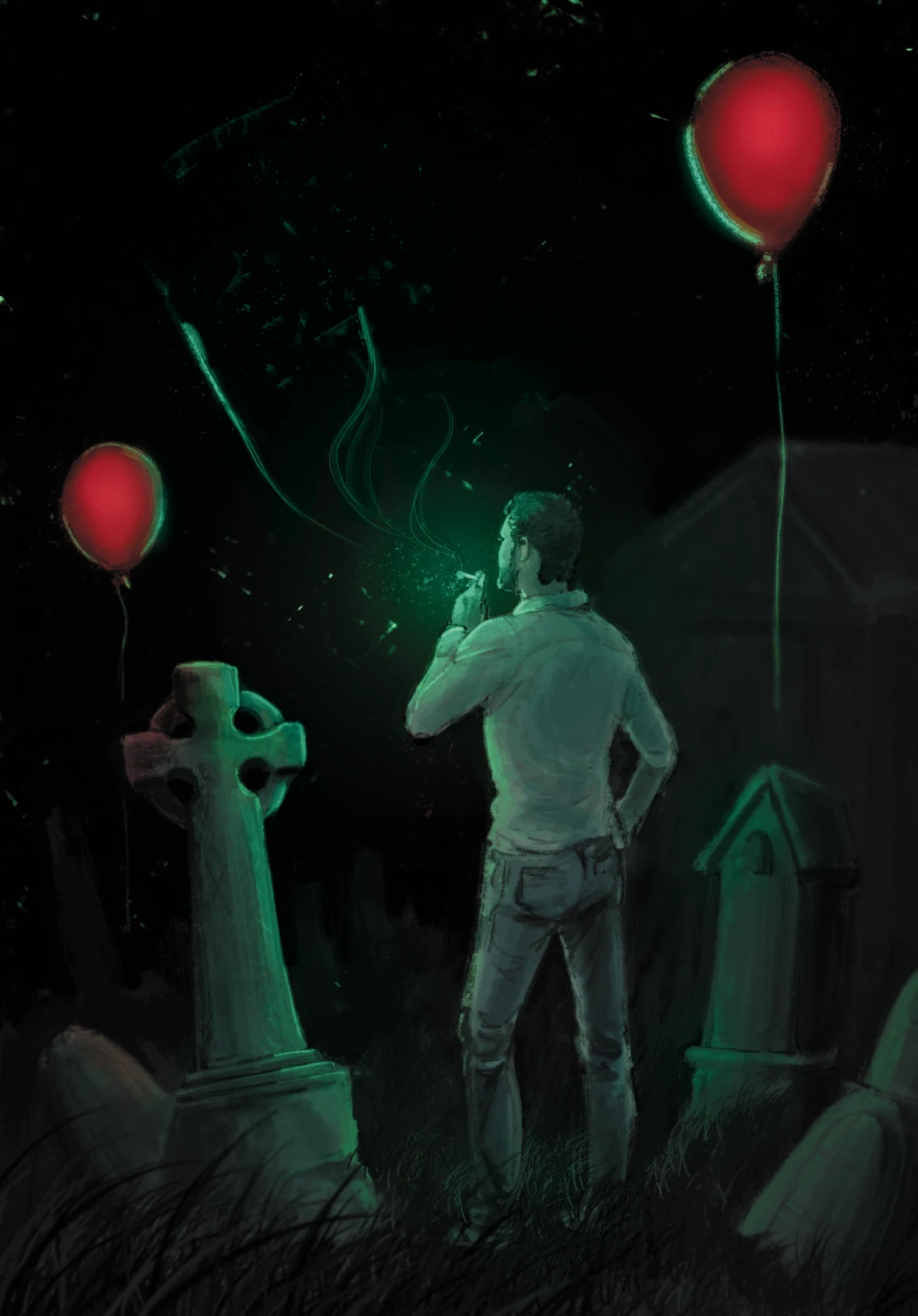

Officer Knox takes a paper out of his breast pocket, then shakes his head and puts it away. “Can I smoke?” he asks me, and when I nod, he pulls a single cigarette and a classic silver Zippo from the same pocket. “We found your Ninja Kawasaki abandoned along Boonsdown Parkway.”

“He was out on a main road?” I ask, surprised.

“Thing is,” says Knox, not acknowledging my question, “the bike was beat up pretty bad, like there’d been a crash.”

“Where’s Jake, then? Is he in the hospital?”

Officer Knox runs his hand over his hair and takes a second drag from his cigarette, then stubs it out on the railing and slips it back into his pocket. I get the sense that maybe he’s new to delivering bad news. “He wasn’t there,” he says. “We don’t know where he is. No one called to report a motorcycle accident last night or this morning. We’re checking the hospital for John Does, in case whoever hit him brought him in.”

“Could he have walked away?” I ask. “Left the bike?”

Officer Knox runs his hand through his hair again. “Probably not, or not far,” he says. “There was a lot of blood.”

I sit quietly, staring down the drive. After a while, Officer Knox says, “You sure you don’t want to go inside? Maybe have a drink to pick yourself up?”

I say, almost compulsively, “I’m not old enough yet,” even though I drink all the time.

Officer Knox says, “Well, let me just make sure I’ve got Jake’s name right, then, so we can keep looking for him.”

I spell it.

“Mackmilan? That’s an odd spelling.”

“Yes.”

“That why you didn’t take his name?” I see him glance down at my wedding finger. I tuck my left hand under my right.

“No,” I say. “To be honest, we aren’t officially married. Never got it together enough to sign the courthouse papers.”

“I see. You have any pictures we could use?”

“On my phone,” I say, “But no prints.” I pull it out and start flipping through it. The pictures of Jake are few and far between. He never liked to take pictures, but there are some of us together, selfie-style. The most recent is a little blurry because it was taken at night and the light is too yellow. I’m in a tank top and Jake has his shirt off. I can’t remember why we took it now, but I’m smiling widely with my eyes too open, and Jake has his little close-lipped half-smile, like always. I hold it out to the officer and say, “Will this work?”

He frowns at it and says, “If it’s the best you’ve got . . . you can send it to this email.” He hands me his card. “Give that number a call if you need anything. If the secretary picks up just ask for Daniel. I’ll let you know if we find anything.”

I stand to watch him drive off. Once he’s gone, I sit back down on the porch steps, bending and straightening his card between my fingers.

I can’t eat for the rest of the day, and I keep thinking to myself, “I should’ve made him come to town with me and make it official. We should’ve been married.” Later I watch the sun dip below the tree line with my arms wrapped around the porch railing, letting it dig in between my ribs and my breasts, hugging it, already missing it, sure I won’t inherit. Our house will go to some distant and unknown relative, and they’ll fill it with things that don’t belong, rob Jake and me from the blank walls. I call the number on Officer Knox’s card when it gets dark. He answers on the first ring and tells me there haven’t been any John Does in at the local hospitals, but they’re checking hospitals farther out, and they’ve also got the dogs out sniffing the woods where they found his bike.

I pace the house for a while, with all the lights on. Around midnight I start to feel tired. I make sure the chain across the front door is bolted and the lock on the knob turned. I lie down in bed, flat on my back, debating whether to pull a pillow over my eyes. When I was younger, I tried sleeping with a mask on so I wouldn’t see things, until I started waking up paralyzed and thinking I’d gone blind. I pull the covers up over my head, which are looser and less suffocating, and try to go to sleep, but the empty space in the bed beside me fills me with a sharp, constant pain, like a rasp of breath whistling over a freshly chipped tooth, and keeps me from closing my eyes.

It was easy to move in with Jake, once things got started. After that first time, the sex got easier—until I locked my eyes on Jake’s one day when he was creaking over me and realized I was no longer filled with fear. He saw it, and he pinned my arms over my head and didn’t stop when I started to flinch away. Instead, he let go of my arms and grasped my hips and kept going long past my screams flew out the open window and into the woods beyond. After, he kissed my neck and smiled and went to get me a beer.

My mother wasn’t too happy when Jake and I showed up to collect the last of my things, just a month after I graduated high school. Then, she was never happy. She glared at Jake and said, “What about college?”

“I can still go to college and live with Jake,” I said. “Are you going to pay for it?”

That shut her up.

The first thing I realize when I hear the door of our closet creaking open is that all the lights are out in the house, even though I’d left them on before bed. I try to lift my head, but it’s heavy on the pillow. In the moonlight from the window I see Jake’s rounded shoulders, and I try to say, “Thank God you’re alive,” but I can’t work my jaw, and I can’t be sure if he’s alive.

I try to lift my arm to reach out to him, try to get my vocal cords to rumble, to say, “Jake,” just that one syllable, but I can’t. He stands there for a long time, and panic mounts in me. If I could reach out to him I could be sure he was real, that he isn’t a hallucination, like my grandmother rising from the coffin. But I can’t move, can’t close or open my eyes, until Jake finally turns and leaves the room, just as he did the night before. I run to the light switch and flick it on, but nothing happens. I grab the flashlight from beside my bed and run down the hall again, sweeping its beam over the floor, trying light after light, but none of the switches work. When I get to the door it’s shut, but the handle is unlocked, and the chain latch is broken, the wood splintered around it. I point the beam into the darkness outside and see nothing, then feel a prickle on my neck and whip around. There’s nothing behind me. I run to my room and dive into bed, ripping my phone off its charger and pulling it under the covers with me. I call the last number in my phone and let it ring until it goes to voicemail, “Officer Daniel Knox, please leave a—.” I try him again and again, feeling panic rising, sobs now racking my body, desperate to do something, knowing that a hallucination couldn’t break my lock. I dial Officer Knox ten times before I take a breath and type in my mother’s number. As soon as I hit the call button I regret it, and jab my thumb repeatedly at the red circle in the middle of my phone, praying the call hangs up before it shows as missed, before she thinks I need her. I call Officer Knox again and leave a message. “This is Casey Compton,” I say, trying and, I know, failing, not to sound like I’m crying. “Please call me back.”

I suppose things had been bad for a while. It wasn’t just that Jake wouldn’t get a job. It was the jealousy, too, but it wasn’t my fault. It was all beer and TV. We’d rarely have those late-night conversations I loved, where we’d lie in our bed, and he’d lean on his arm and listen, about how hard it was when my parents were getting divorced, about how scary the waking nightmares were, about my ideas on good and evil and anything else I’d been thinking of, about the periods of my childhood I just couldn’t remember, especially summer vacations, how that lack of memory terrified me. He’d hold my hand if I was talking about something sad, or if I was just talking, he’d trace his fingers or his lips along my bare stomach and breasts. But it all stopped, and after a while, it was either sex or beer between us. Once, outside the grocery store, waiting for my ride, he overheard me talking to Will, one of the cashiers I went to high school with.

“If there is a God,” I said, “I don’t think he’s good. Otherwise, there’d never be war, would there?”

Jake came out from behind one of the brick columns at the store, holding a bunch of daisies and looking livid. “I parked and got you some flowers. Let’s go.”

We walked to his bike. Jake thrust the flowers at me and started up the bike, not giving me time to put on my helmet before he started driving. On the dirt road to our house, I watched the speedometer climb to eighty and grasped tightly to Jake’s waist. We stopped in front of our house in a cloud of dust. Jake left the bike running and said, “So what’s that guy want from you?”

I got off the bike. “Jake, we were just talking.”

“Yea, same way you talk to me. What do you want from him then?” He spat the words at me.

I felt myself starting to shake, holding the flowers in both hands before me like a bride. “I don’t want anything, Jake, I don’t. I just want from you. I miss you. We never talk anymore. Not like we used to.”

Jake stared at me for a minute, then grabbed my hips and pressed his lips against mine, kissing me fiercely, pushing me back towards the bike. I felt a searing pain against my calf and screamed, forcing Jake’s tongue out of my mouth, but he held me tightly a second before letting me writhe away. There was already a welt rising where the exhaust pipe had burned me.

“You did that on purpose!” I screamed at him, tears filling my eyes.

“Casey, how could I ever?” he said, already reaching out to wipe my face. “I love you.”

When Officer Knox calls me the next morning he says he’s got some news, and that he’s bringing another officer with him. Now that it’s light I go to the breakers and find them switched off. I turn them back on, then walk through the house turning off lights to save energy. I wait to tell the officers about the break-in until they pull into the drive, but when the new officer gets out of the car I don’t say anything at all. Officer Knox smiles at me, but he looks stooped in this other officer’s presence, who is much shorter and older than he is, and who doesn’t take off his sunglasses.

“Ma’am, is this Jake Mackmilan in this picture?” The officer doesn’t introduce himself. Instead, he pulls a small photograph of Jake out of a manila folder. Jake looks younger, his head more neatly shaved than it is now, edged nicely in the front, and he’s in uniform, his mouth straight and proud.

I say, “Yes, that’s him.”

“Did Jake ever mention his time in Afghanistan to you?”

“Some,” I say, “but he didn’t like to talk about it.” I glance at Officer Knox, who’s staring over my head.

“In that case, we’ve got to turn this case over to the boys at the D.O.D.”

“The what?”

“Department of Defense. Jake went missing a few years ago. Presumed dead, but if he’s alive and never reported back, he’s a deserter, and that’s for the D.O.D. to handle.”

Officer Knox steals a glance at me and presses his lips together.

My voice shakes as I say, “So you’re not going to try and find Jake?”

“Sorry, ma’am,” says the new officer, not sounding at all sorry, “but that’s protocol. The DOD will start working on it, and if they find him, they’ll probably arrest him. And you’re sure you haven’t seen him since he left? He didn’t come back here?” He takes off his sunglasses and stares at me through small eyes, as if he expects me to suddenly confess to harboring a fugitive.

“No,” I say, feeling small, and angry at the officer for making me feel this way.

“Well let us know if you hear from him,” says the officer, and he starts walking back to the car. I take a breath and call at his back, “Thanks for being so concerned about Jake. It really means a lot to me that you’re making sure he’s okay.” The other officer lifts a hand as if waving, but doesn’t turn around or acknowledge me in any other way. Officer Knox presses his lips together, then starts to turn away, too. I don’t know what makes me do it, except maybe that he feels like my last hope, but I reach out and touch his arm.

“Can I talk to you?” I say in a low voice, and head towards the porch. He looks over the shoulder at his partner then follows me.

“Listen, I’m real sorry about all this,” he says. “I wish I could help. And to be honest, if I’d been bombed or something, over in Afghanistan, and I could run away and never look back, I would. I don’t blame Jake for that.”

I swallow and open my front door. “Someone broke into my house last night.”

Officer Knox’s brow furrows. He leans in to look at the door, then looks back at me. “Did they take anything?” he says. I shake my head. His eyes look sad, and he reaches out to touch my arm. “Did they do anything? To you?”

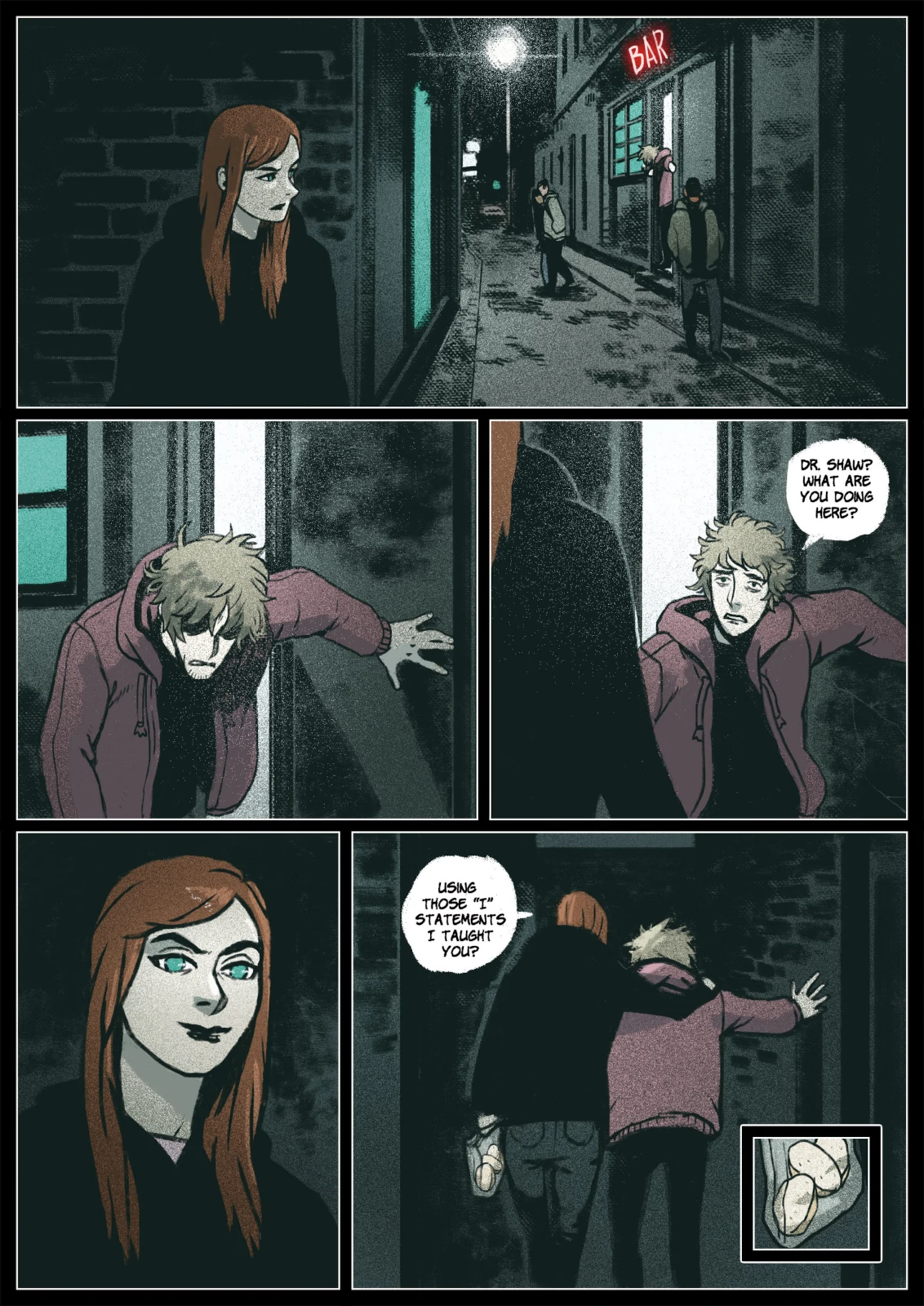

“No,” I say. “They just—they stood over me. I have this problem, sometimes, where I can’t move when I wake up. Otherwise, I would have chased them.”

“Did you recognize them?”

I stare for a second at Officer Knox, wondering if I can trust him, then say, “I think it was Jake, but I’m not sure. It was dark.”

“Is there anywhere else you can stay tonight?”

I shake my head, thinking what my mother would say if I showed up on her doorstep, if she’d even let me in.

Officer Knox stares at me, his mouth tight. “Listen, once I get back to the station I’ll call you, then I’ll try to come over tonight, okay? I can at least change your lock, and fix the chain. Did you feel threatened, when he was here? Did he ever threaten you?”

I shake my head no, just a slight shift of my chin from side to side.

He says again, “I’ll call you,” then trots down the porch steps and jogs to the police car.

I walk down to the creek again, but the spot still looks untouched. Every time the other officer’s voice comes into my head, saying, “deserter,” I push it down, thinking, “Knox is right. I’d do that, too,” and, “I’ll talk to Jake about it when he gets home. It can wait till he gets home.”

When I remember my father, if I do at all, I think of him on our summer vacation between first and second grade. We drove out to Texas in my father’s truck, my mother with her long tan legs up on the dash, my father drumming on the steering wheel, and me squeezed between them in the hump seat, my lap belt loose. My mother’s bare thigh pressed sticky against mine in the heat, and when she slept my father’s hand rested on my knee.

My mother slept a lot on that trip: in the truck, in the motel beds and out by their pools, because “it was her vacation dammit” and she needed that sleep. My father took me to eat barbecue and tour the town where he grew up. I remember the cut watermelon stand by the side of the road, flies feasting on the dripping red juice, and a hill where we watched the prong bucks graze at dusk. My father sat next to me, massaging the back of my neck and kissing my left shoulder. He looked at me sideways, his eyes that same blue as the just-set sun, and said, “Casey, you’re growing up so fast.”

When Officer Knox comes back that night he’s still in uniform, and he brings a new chain and doorknob, gold-colored instead of the silver I used to have. He takes out his silver Zippo and his hands are steady this time as he lights what he calls “a happy hour cigarette” out on the porch. “I used to live out in the woods like this, too,” he says, drawing deeply on the cigarette. “It was the best. My brothers and I running through the trees all day and splashing in the creek. At least, that’s how I remember it, but I know I went to school sometimes, too. Still, it feels like my whole childhood was spent outside.”

“I grew up in a suburb,” I say.

Inside, Officer Knox sets to work on my broken lock. He hands me the old chain and gestures for the new one. When I hand it to him his warm fingers against my palm send a shiver up my spine. “Cold hands, warm heart,” he says. I smile and watch as he screws the new lock into place.

“I was thinking,” he says, “If you’d like, I can stay the night here and keep watch. I live alone, so there’s not anyone to miss me at home.”

“Um,” I say, and drop the screws I’m holding for him. He bends quickly to pick them up, but stays bent over, staring at my leg. “What happened here?” he says, reaching out and brushing the long, purple scar from the exhaust pipe.

“Burnt myself,” I say, trying to sound casual, feeling my throat tighten, “On the bike.”

Officer Knox stands and stares at me, his eyes locked on mine. “You sure Jake wasn’t mistreating you? You sure?” I start to shake, and Officer Knox grabs my shoulders then pulls me into him. I stay still in his arms, my own arms by my sides, thinking that I should push away, but I can’t get myself to take that first step. For some reason every time I try I worry that I’ll offend him.

“You’re safe,” he says near my ear in a low voice, his hands rubbing my upper back. “I’ll stay the night, if you want. Not as an officer, as a friend. We can make sure he doesn’t hurt you anymore.” Officer Knox pulls me in closer, and I think I feel his gun brushing my hip. He leans back a bit, and I’m still shaking, but he cups my chin in his hand and says, “Is this what you want?” I can’t move or speak, or maybe it’s just that I don’t know what to say, but he lowers his mouth to mine and presses his tongue against my lips. I open them, my heart beating quickly, and his tongue snakes into my mouth, deep enough that for a second I worry I’ll suffocate. He kisses me for a few minutes, presses me against the wall, then pulls away and lifts me. He carries me toward the bedroom. I wonder vaguely if he knows where he’s going, and I look over his shoulder, where the new door handle lies forgotten on the floor.

After, Officer Knox lies on Jake’s side of the bed. He says, “I’ll go get a towel.” He comes back with our good hand towel and tries to hand it to me, but when I don’t move, he wipes it between my legs and kisses me on the mouth.

“You must be tired,” he says. “I’ll finish the door and then come sit with you and keep watch. You sleep.” He turns out the lights.

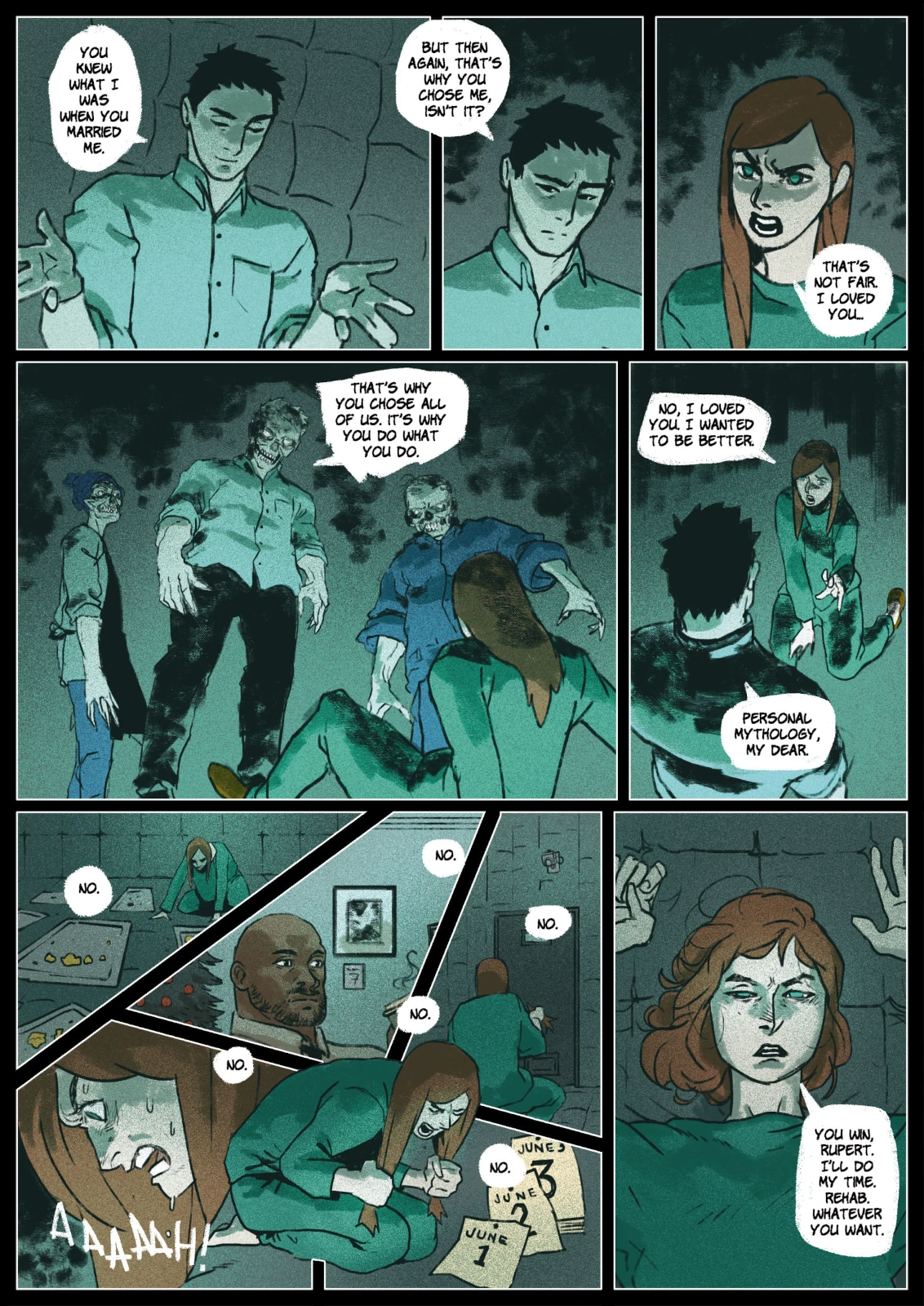

When I wake up Officer Knox is sitting at the end of my bed, still naked. He turns to smile at me, then stands up. “I knew you were a dirty rotten cheater,” he says. I try to lift my head and say, “What?” but I can’t move. He says, “You seemed so sweet, when I chose you all those years ago, so scared, like you needed me.” He turns away from me, hunches over and moves like he’s laughing, big belly laughs, but no sound comes from him. He reaches in the air above him, as if he’s grabbing for something, then turns. Jake is standing where Officer Knox was. With the moonlight behind him I can’t see his face very well, but I know his shape, I know it. I focus on my fingers, try to twitch one of them, to wake up out of this bad dream. Jake says, “I knew it, Casey.” I think, “Wake up, wake up,” but Jake comes close to me again, leaning into my face. His breath is putrid, like roadkill. He says, “I never thought, when I came here, that I’d like it. But it was so easy to become someone people trust. Especially you, after all that stuff with your father and mother. Women like you, who get hurt the most, you become so vulnerable and sweet. No one like that where I come from. But I didn’t think you’d hurt me like this. Casey.” He backs away again and bends over, doing the same laughing motion, without sound, then moves his arms and grasps in the darkness above him. When he looks back at me his skin is smooth and glistening, and he’s wearing the antelope skull. I feel my breath catch in my throat as Jake walks to me. He traces a burning hot finger over my stomach. I flinch away from his touch, and Jake jerks his hand away. I ball my hands into fists at my sides. I blink a few times, then start to sit up, expecting Jake to dissolve, or perhaps to take off the antelope skull and say, “Ha, got ya,” but he puts a searing hot hand on my shoulder and pushes me back into the pillows. With the other hand he pinches my nipple. I think I hear someone calling my name, or maybe a pounding at the door, but it’s as if I’m underwater, barely able to hear, unable to breathe.

When I wake up the next morning, I think for a moment that I’m in my childhood bed at my parents’ house with the polka-dotted comforter. I roll to my side. When I see the hand towel on the floor the night before comes rushing back to me. There’s a single damp sheet wrapped around my body, and I fight my way out of it, knocking an unopened bottle of Gatorade to the ground. There’s another on the bedside table, along with the first aid kit I keep in the bathroom, the thermometer and a bottle of calamine lotion sitting on top. There’s dried pink calamine on my stomach and covering my shoulder and breast. I lick my thumb and rub it gently away to reveal burn marks on my skin, where I remember Jake touching me. I look around my room for a weapon and settle on the silver flashlight, then creep out into the hall, ready to run or fight. I check the bathroom, then scan the living room and kitchen, my eyes falling on a box on the table. It’s filled with chocolate doughnuts, and scrawled across the top is a note in sharpie.

Casey,

I hope you’re feeling better. Be sure to drink your Gatorade. I’ll check on you after work. I didn’t want to leave the house unlocked, so I left a key for you and took the other with me. I’ll give it to you tonight.

Get some rest.

—Daniel