Mouth of God

Dinah was content with her sister-wives and never complained about the chores she had. She savored how her fingers pruned after washing the sheets, mesmerized by the iridescent suds that illuminated the pores and cracks in her hands. Hanging the bedding to dry outside their mountain home, away from society’s burning gaze, felt like communing with Heavenly Father. The white fabric undulated in the breeze as if the Holy Spirit moved through it. The aroma of fabric softener and bleach mixed with the earthen scent of desert sandalwood was her definition of peace. Dinah didn’t think she could be happier until her husband told her it was time to bear a child of God.

Electricity coursed through her that day, her whole body vibrating with anticipation. She tucked clean, white linens around the bed. Smoothing them across the mattress, she willed it to be a pure and adequate place to conceive her child. She prayed for a son. Strong and brave and ready to hold the Keys to the Kingdom of Heaven.

The ecstasy of conception was nothing compared to the rage and shame of her miscarriages. By her third loss, Dinah couldn’t find the Spirit in daily routines. The white sheets she hung to dry no longer reminded her of temple rites but of ghosts from a Stephen King novel. Stolen from supermarket ventures, she consumed wicked stories while her husband was busy with her sister-wives. More and more he left her alone to read and do the laundry.

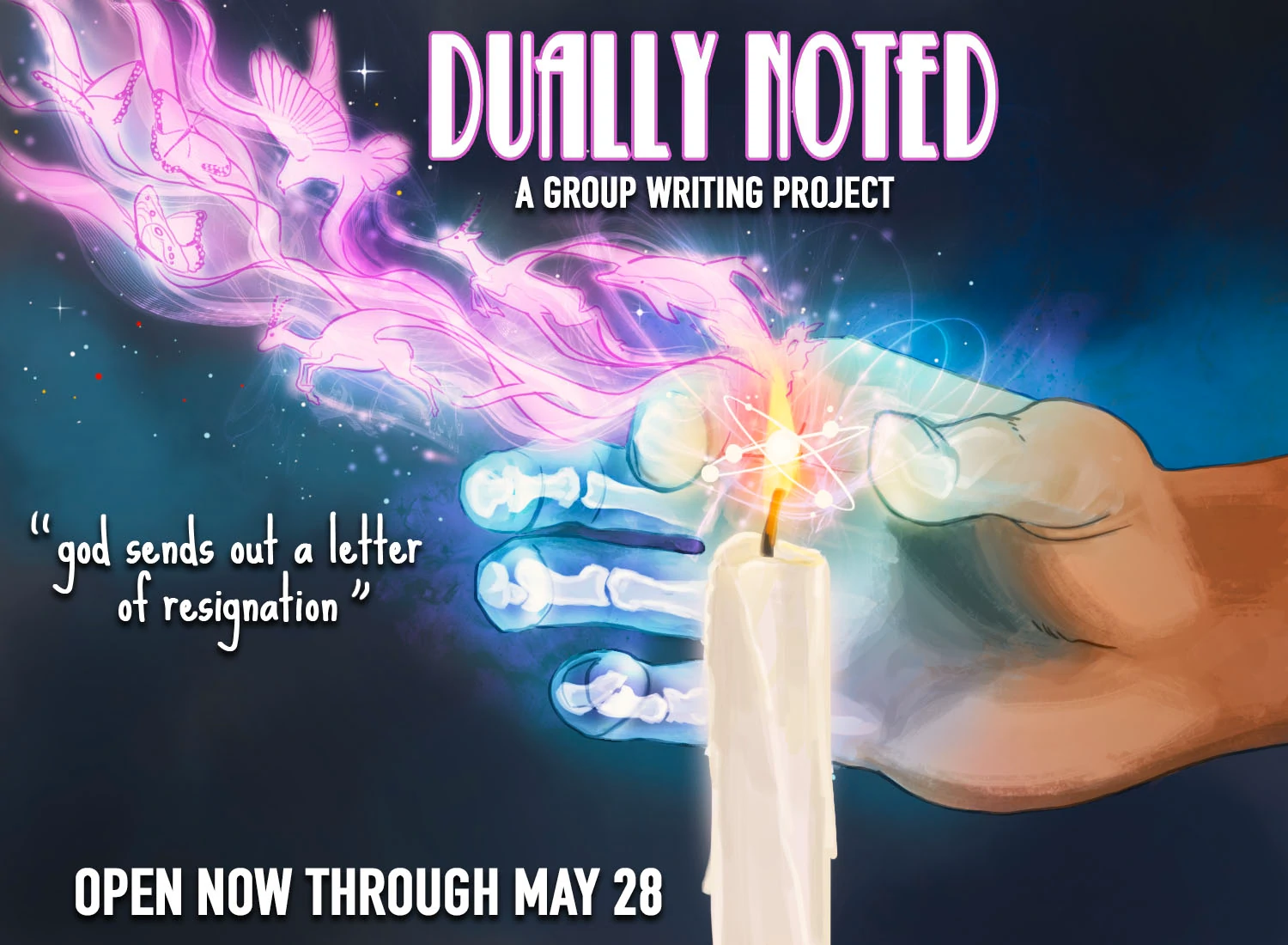

But no matter the amount of bleach, Dinah could still see the stains of her failure, a faint red orifice. Like a letter from the mouth of God, she knew, He had abandoned her.

He had quit.

She tore down the sheets and screamed back at the red cotton lips, called them names, and swore her revenge on Him. On the God that had resigned on her.

Throwing open the linen closet, she wrestled the bedding to the ground. White cotton, grey wool for winter, even the little green teddy and flower sheets—a hand-me-down from her favorite sister-wife—Dinah heaped them all into the middle of her quaint kitchen. She rummaged under the sink until she found an unopened bottle of rubbing alcohol and emptied it. The fumes made her cough. She encircled the bedding with candles, wax pooling onto the hardwood floor.

When the flame caught hold of the cotton, Dinah was surprised how quickly it spread. The pile transformed into a smoldering blaze; the heat warming her legs, her cheeks. Her eyes watered from smoke. Once the flames were high enough, Dinah threw the stained sheets on. She watched God’s mouth, pale pink and taunting, burn into a fine ash before she left the house. In her husband’s Chevy, Dinah adjusted the seat and wriggled the rearview mirror into place. Her gaze drifted from the burning home to the road ahead of her. The engine rolled over, thrumming beneath her, and Dinah made her escape to Phoenix.