“Grandmother, look!” Off to the side of the path they walked every morning loomed a large, white tent. It stood in stark contrast against the bleak, gray landscape ravaged by years of weather extremes that fueled famines, pandemics, and wars. “Let’s go inside.”

The woman held the child back.

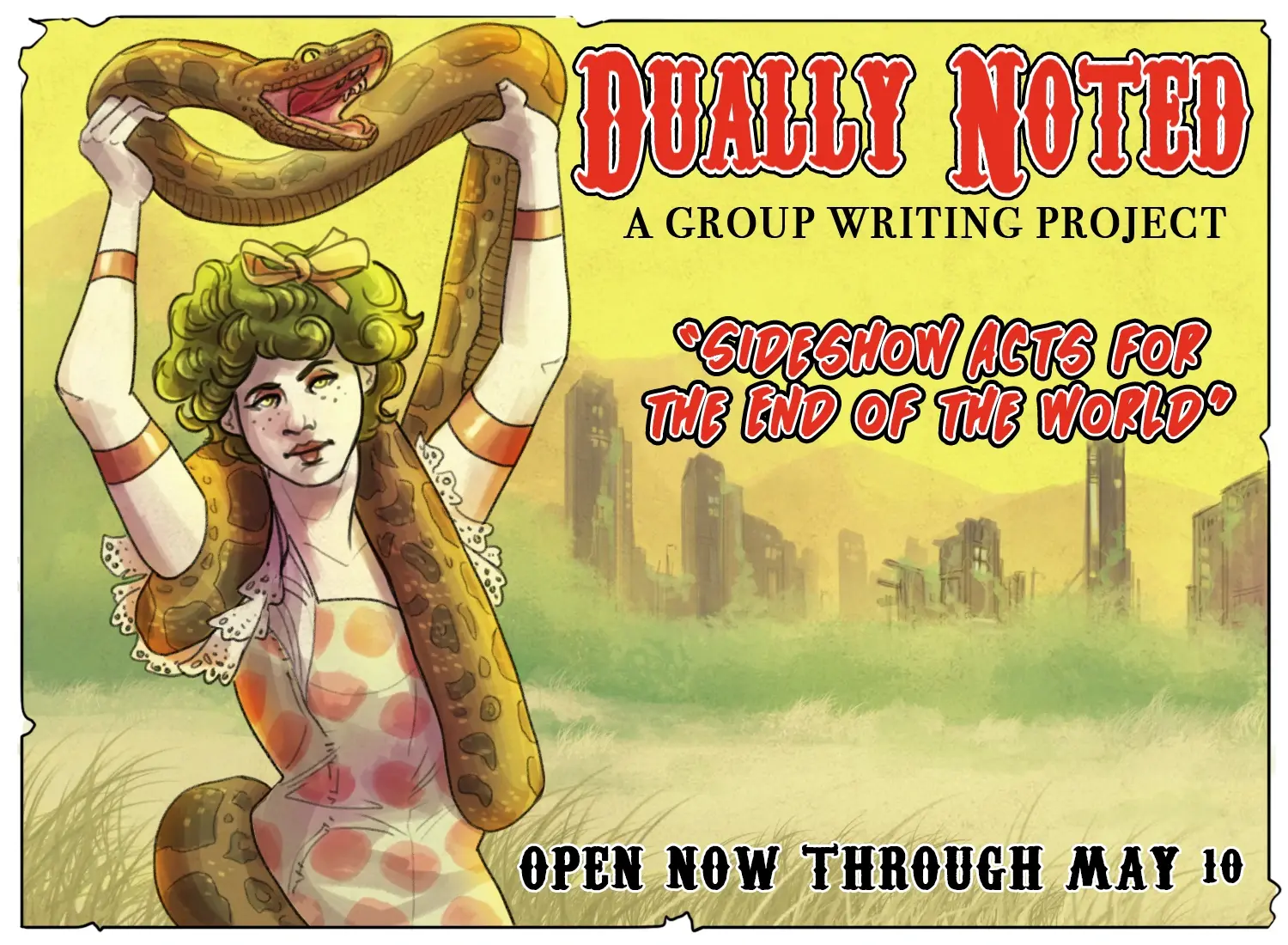

Spying the pair, a man hollered, “Step right up! A world of possibility awaits.”

“I want to see!” declared the child, mesmerized by a poster of a hummingbird.

The woman covered the child’s ears. “There are no possibilities, only death,” she snapped. “You know that.”

“Yes.” The man nodded. “Still, we’re not dead yet. We have three days.”

The woman scoffed. “Some choice: die a slow death along with this world, or visit the Center in three days, and . . .” She sighed. “An ignoble end to what’s left of humankind, either way.”

He pointed to the child. “She doesn’t know?”

“No. I can’t find the words. She’s so full of life—so inquisitive, caring, optimistic, kind. She’s a force of nature, this one, and she deserves better, but we can’t survive on her will to live alone.”

“Why not allow our simple sideshow acts to entertain you until then?”

“Your distractions will change nothing.”

“No, but perhaps you should let her have this.”

The child pulled away, tugging her grandmother toward the entrance. “Come on!”

“Alright, alright.”

Inside, the tent was enormous. The center corridor extended farther than they could see, with openings lining each side. People were coming and going, chattering among themselves about the marvels they had witnessed, things adults barely remembered and children knew only from stories.

In the first room, they watched in awe as spiders wove their webs. In another, seeds sprouted from rich, dark soil. They grew into plants that produced fragrant flowers, delicious vegetables, and luscious fruits. The child liked daisies and peaches the best but didn’t care for broccoli. In the next room, bees pollinated flowers and produced honey. “This is good!” the child squealed, when offered a taste. Further on, they saw birds build nests, hatch eggs, and teach their young to fly and sing.

They wound their way through the tent, and in each room were given glimpses of nature as it was, before it was spoiled by recklessness and greed. The grandmother wondered how it could be that everything appeared as if it was happening in real time; the child absorbed it all.

When they reached the end, the child asked, “Can we go again?”

“I’m afraid not,” the attendant said. “It’s time for you to go home.”

Hand in hand, they emerged with the other explorers—into a lush, welcoming world teeming with possibilities.

“How can this be?” the grandmother inquired. “How long were we inside?”

“Long enough for the world to heal.”

“Why us?”

“Them.” The attendant nodded at the children. “You’re right. They deserve better, and they need you to help them build a future. Teach them to do things right this time.”