First off tell us about your new book How To Play The Necromancer’s Theremin and its character psychedelic sci-fi writer Rocco Atleby

Griffin: How To Play A Necromancer’s Theremin is about a cult classic author named Rocco Atleby and his literary world called the Patasphere. Rocco is this archetypal mid-century wise old sci-fi author sage and the whole world, that he may or may not have created, is obsessed with him. There are Rocco-themed bars, Rocco pilgrimages you can purchase, and much more. The world is littered with his face and words.

The book is about the cult of personality, our clout-obsessed showbiz culture, and the search for authenticity and spiritually-meaningful living in our techno-infused carnival of political horrors called late capitalism.

Quay: Rocco Atleby was born in the middle of the pandemic when Chase and I were both laid off from our jobs. We went on a lot of walks together to pass the isolated time, especially late at night when we were restless and didn’t have any jobs to get up for in the morning.

I don’t remember exactly when Chase started talking about Rocco and his admirers, it was like he had always been there, like someone we were remembering together. He is definitely Chase’s brain child.I feel so lucky that we have the kind of relationship where Chase always wants me to word play with him and live and interact within his imagination with him.

What was it like writing a character from back in the days of fringe drug culture when we now see that psychedelics have fallen more into the mainstream for mental health treatment?

Griffin: Writing Rocco was like having a kooky old uncle move in with us. It was a bit of a sitcom episode. But instead of dividing the house in half with duct tape, the Griffin-Quays on one side and Rocco on the other, we sequestered Rocco to a mother-in-law suite located above the detached garage. And he was only allowed into our home when we gave him permission. So, I guess it was like a sitcom about a friendly, kooky vampire uncle. Man, I gotta pitch that to someone. We could call it Vuncle.

We’d ask Vuncle questions about the old days and his excessive toxic creative behavior and then when Vuncle came to be too much and we politely asked him to go back into the suite he politely went back into the suite.

Quay: As someone who decided to begin the journey of total sobriety when the pandemic started (no alcohol and no cannabis, and coffee has been my only vice for 3 years now) it was very therapeutic for me to write about these wild characters who totally distorted and bastardized the magic of words and used them for drug-like purposes. It almost made me feel even more sure in my decision to live life sober and uninhibited by mind altering substances. And saying all this isn’t to knock anyone’s lifestyle by any means, but it was a good way for me to find perspective personally.

It was really fun to write about a character from back in the days of fringe psychedelia because I have always been fascinated by the stories of Carlos Castaneda, Philip K. Dick, and Terrence McKenna to name a few. I have always been drawn to tales of the otherworldly and breaking through our reality into shared realities. The way Chase used [these] books as that vehicle in our novel was just so creative to me, I’m literally astounded continuously by his unmatched imagination.

How is it like looking at the work of those sixties and seventies psychedelic sci-fi authors, whose ideas were celebrated by readers for being avant-garde and then one sees video of Philip K. Dick speaking at the 1977 Metz SciFi Convention and he presented the VALIS trilogy as possibly real? How does your work deal with the Borgesian conundrum questioning “whether the writer writes the book or it writes them”?

Griffin: Whenever people ask Alan Moore where his ideas come from he says, “I have no idea. A voice just shows up and does the work.” When I sit down at the old desk and write, not much happens for the first hour or so. Some verbs and nouns tumble onto the page and dance like a herky jerky robot. Don’t get me wrong. Sometimes the herky jerky robot can be a fun spectacle for both myself and the reader, but that robot dance along with all the various types of fiction dances must be on our terms and on purpose.

I think this Muse, VALIS, is what PKD was hearing (and seeing sometimes) and because the notion of positive “support system” didn’t quite exist back then and because the psychology world was in the midst of rapid transition and constant change back then and because of whatever the underlying mental health issues he suffered from his whole life and because of the amphetamine use, he sometimes took his Muse experiences to be very real.

I guess when I watch that video of PKD at the Metz, I feel lucky. I feel lucky to have a modern perspective. I feel lucky to not take myself so seriously (whether it’s on purpose or not). I can for sure understand PKD’s Metz exuberance. Sometimes when I have a creative breakthrough I feel like I want to hold a press conference too. I won’t lol but sometimes I want to.

Quay: Chase and I definitely don’t take ourselves so seriously as to think anything we write has any basis in this tangible shared reality. Do artists create realities? Absolutely. But do we think in some multiversal plane Rocco Atleby is hurtling through time in a fat tornado clock? Not likely. I have always been tickled by the juxtaposition of the writer and their intentions versus how their work is received. Intention versus reception and interpretation is an animal all of its own.

And when it comes to the psychedelics and admiring their groundbreaking strides, we can love and revere their work without considering it as a religion of truth.

As far as the Borgesian conundrum, it’s a paradox that Chase inserted I think quite intentionally into our book in a few different ways. My favorite example is the character Holger, because while we wrote the book, I asked him, “So did Rocco write Holger into existence, or is it more of a Stranger than Fiction situation where Rocco is omnisciently narrating and guiding the fates with his pen?” And Chase has still remained mysterious, even with me, in his answers, because I think maybe it’s a little bit of both.

What is it like for you two writing a book together as a couple with a family together? What is your process?

Griffin: Christina and I Yes-Anded this book during the pandemic as a way to pass the time, jokingly muse about the nature of things, flirt with each other, and try our dang hardest to make each laugh so hard we piss ourselves

Quay: Writing a book with Chase was a purely magical experience. It was like he invited me to live in his head for a while, because Chase deserves full credit for the birth of the Roccoverse. Writing this book with him was like being invited on a road trip. And he handed me this wild map that only I could interpret and we hopped in a flying clown car and I played navigator on this wild ride to another dimension where occasionally I would completely take the wheel. It really says a lot about Chase’s ego, he genuinely wanted my voice to be present in his work, and it became ours. It started off as me just “editing” and “taking a look” but I started asking if I could tweak things or add sentences and then scenes, and before I knew it I had written so much that I said “Chase, I don’t feel comfortable not having my name on this, what if this gets published and someone quotes my words and the by line says Chase Griffin? And he said, “Scroll up to the top of the document,” and he had already put my name under his. He’s quite devilish really.

We wrote the book like a conversation in a Google document. That way we could both work on it at the same time and even see where the other person was in the document while we wrote. We heavily got into writing when I found out I was pregnant with our first child in 2021. My stepson was 7 at the time, so I would go to work, come home, cook dinner for us while Chase was at work, put our son to bed, and I wouldn’t start writing until 9 o’clock at night some nights. It was really hard work, and especially since I was pregnant writing this felt like a happy fever dream.

Kelvin Matheus writes that your book is “some type of esoteric improv that explores Borges’ theory on causality as the main problem of the literary arts”. We discussed Borges and psychedelics, fringe sci-fi but improv have more connections than people know when you look at the biography, tall tales and teachings of improv guru Del Close. How familiar are you both with Close’ work, bio, and this teaches of “yes and”, truth in comedy” & “working at the top of your intelligence”?

Griffin: Del Close is another one of the great psychonautzzzz. He’s almost never credited as one, but he is. He was even a Merry Prankster and the SNL crew’s house metaphysician. Del Close was from that long line of, from High Weirdness, “subcultures…united in their desire to affect a complete discontinuity with the conventional reality.”

Improv comedy is one of the big themes, concepts, and engines of our book. Christina and I were constantly playing Del Close’s game, The Harold. And Wasteland has been a big inspiration on my creative life. The Harold and Yes And are like spells. Improv comedy has always fascinated me. It is like the creation of brief anarchic pocket universes. Improv comedy, in my opinion, is a modern day esoteric magickal ritual.

Quay: I am extremely well read, but Chase is the comedy manual, philosophy nut so this question is admittedly a better target for Chase. I’m more of a historical fiction, fantasy reader. But I think that’s what makes our novel so fascinating. If you’re an avid reader of philosophy and improv comedy, you’ll see so much behind the lines that Chase put there on purpose, but if you aren’t, like me, you can still totally understand and interact with the book.

What sci-fi writers of this time period do you wish more readers would rediscover? What draws you to their work?

Griffin: Ursula Le Guin, Octavia Butler, Samuel R. Delany, and Michael Moorcock. Borges isn’t sci-fi in the traditional sense and he’s older than the new wave sci-fi we’ve been discussing but I think he kind of counts because he had a renaissance towards the end of his life in the 60’s and 70’s when he was discovered in the US by this generation of writers and readers.

I always recommend Borges (Borges and Mary Shelley are probably my all-time favorite writers) and his trippy brain-wrinkling reality warping tales like The Library of Babel, Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius, Funes, His Memory, The Immortal, The Aleph, and so many others. And yes, if anyone was wondering, more than anything else, How To Play A Necromancer’s Theremin is our attempt to write a full length Jorge Luis Borges novel.

Where can readers find you online and check out your work?

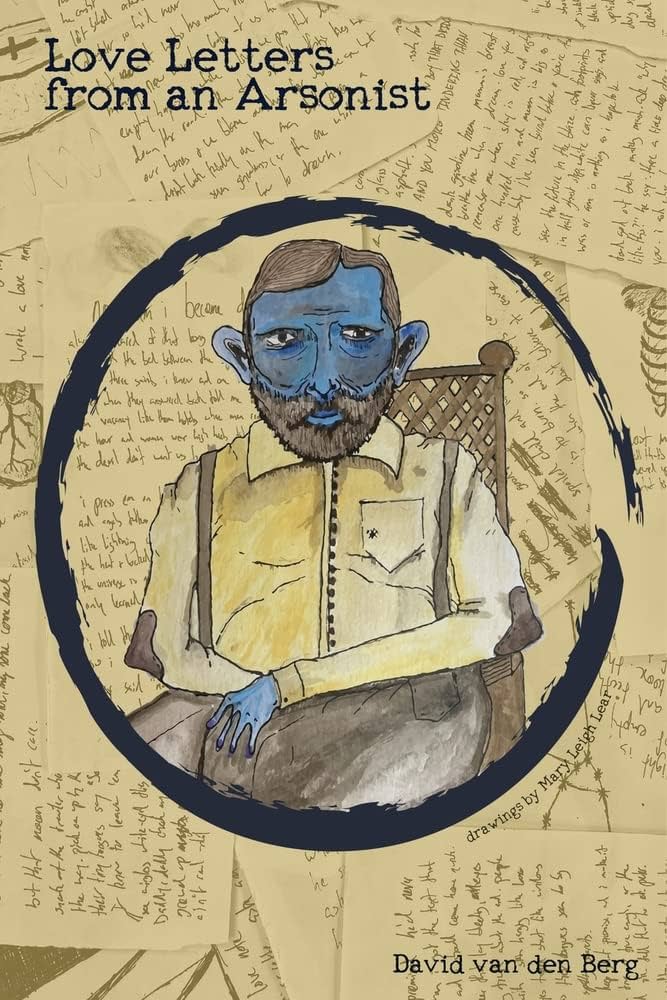

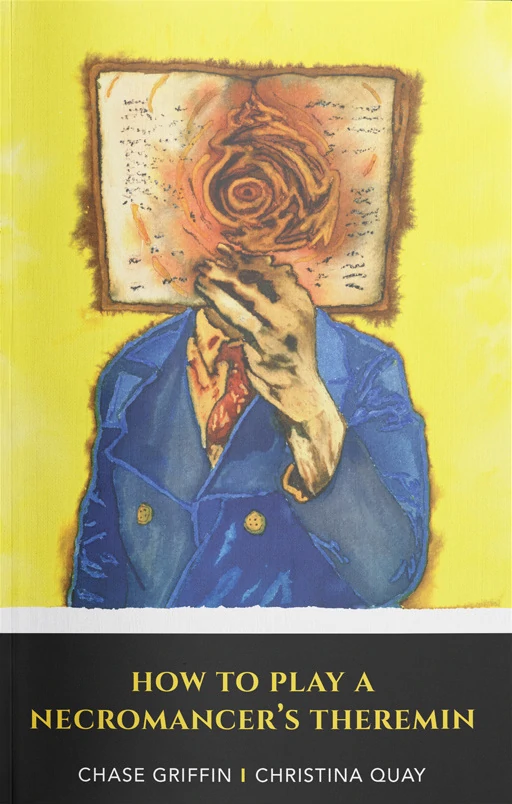

Griffin: How to Play a Necromancer’s Theremin will be published by Maudlin House on September 28th. Long Day Press published my debut novel, What’s On the Menu?. That book is about sunbaked restaurateuring and tainted water supplies. My Instagram @sleepcook_ is where one can find all the updates and extra nuggets.

Quay: My paintings and drawings can be found on my Instagram @qualien_.