A crowd gathered the day before Sushi Maekawa closed.

So Ayami wanted to say. In reality, only four people lingered outside the glass storefront. If Sushi Maekawa still drew crowds, they would have soldiered on instead of closing.

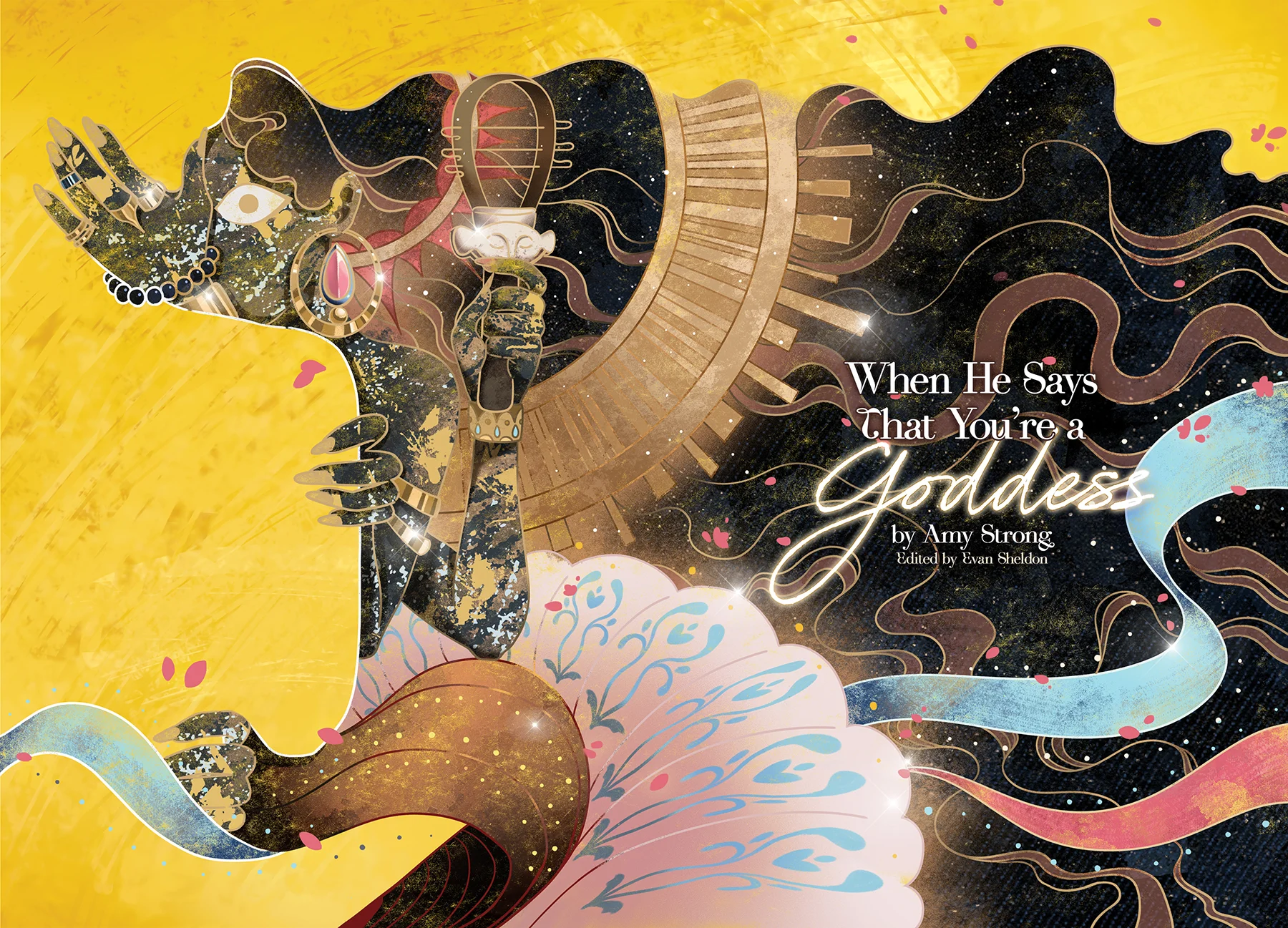

She glanced at the tank on the counter and met the gaze of one of the fugu. Its round dark eyes seemed accusatory, though whether it wished to say Why would you eat me? or Why won’t you eat me? Ayami couldn’t tell. Considering the number of fugu they still had in the back, this one was unlikely to be consumed today.

She rubbed her right hand—beginning to show wrinkles—against her forehead. Had she become as sentimental as her mother? Twenty-six years a fugu chef, and never before had she assigned thoughts to her fish.

Toshi, his uniform starched and spotless, flipped the sign from Closed to Open. He unlocked the front door, but not one among the four-member crowd entered.

Ayami glanced at the clock. Were they opening already? 10:00 a.m. So, it was opening time. More and more, time had become the domain of digital clocks and flashing numbers rather than the world outside, where nights were starless and days endlessly smoggy. During Sushi Maekawa’s last major renovation, they had changed the dark cherry wood tables for a lighter finish to give some illusion of light.

All three fugu turned away from Ayami. They were torafugu, with black blotches on their sandy yellow backs and some of the deadliest poison to go with their exquisite taste. One of them nuzzled the glass, round eyes directed at somewhere beyond Ayami.

Ayami followed its gaze to the man seated behind the counter. Maekawa Gen, proprietor of Sushi Maekawa. Arms crossed, eyes hidden behind ever-present sunglasses, bald patch gleaming beneath the LED lights—another concession from their last renovation and one Ayami had suggested. Most would mistake the sunglasses for some outdated fashion statement, but Gen had confessed to her that even indoor lights hurt his eyes these days.

Ayami reached out and tapped Gen on the shoulder. “Sit there brooding for too long and you’ll scare off all our customers.”

Gen turned. Ayami knew him well enough to read his expression behind the sunglasses: annoyance, mild. “Look at them,” he said, gesturing at the gawkers outside.

“I know. Milling around the door, not coming in when it’s their last chance.” She forced a smile. “They don’t know what they’re missing.”

“No. Look at him.”

It took Ayami a moment to figure out who Gen was talking about. A young man in an oversized t-shirt leaned against the storefront glass, unzipped backpack at his feet, Quickscape helmet in his hands. The helmets didn’t offer the full Dreamscape experience—their nodes weren’t that powerful—but they were immersive enough if you wanted a quick break from reality.

The man slipped the helmet over his head and sat down on the sidewalk. He fell still, reacting no more to the people around him than the glass did.

“Can’t he read?” Gen growled. “‘No Dreamscaping.’ Says right there on the window.”

“He’s not inside the restaurant yet,” Ayami pointed out. Nor will he ever be, like the millions of others lost to the Dreamscape.

Gen snorted and turned away. No matter how Ayami felt today, he must’ve felt worse. Sushi Maekawa—once Fugu Maekawa, before changing its name in a futile attempt to attract tourists—had been in Gen’s family for generations.

The bell—an old-fashioned one, for this Gen had refused to give up—rang. Two people Ayami recognized pushed past the three gawkers and one Dreamscaper to enter. Uehara Reiko was around Ayami’s age, her grey-streaked hair knotted in a bun. Her son Minoru was in his twenties and updated his hair like other people updated their multi-tabs. Today it was cerulean blue and spikey. Over forty years ago, when Ayami was in second grade, her older brother had returned home sporting a similar hairstyle. Their mother had chased him around the house with a razor. Nowadays, Minoru’s peers would consider him a dinosaur; who bothered with flesh-world styling when it was easier to make a cool avatar in the Dreamscape?

Reiko’s eyes fell on the fugu tank as Toshi led them to their usual seats by the window. Ayami couldn’t remember them sitting anywhere else recently since their table was hardly ever taken. Gen had offered them private rooms at no extra charge, but Reiko had turned down the offer, saying she preferred the window even if the sun rarely broke through.

“What are you going to do with those guys?” Reiko asked, gesturing at the fugu. Toshi shrugged and muttered something noncommittal. Ayami could’ve answered. The fugu would be sealed in locked containers and disposed, like their poisonous parts were. A waste, but at this point shrinkage was the last thing Sushi Maekawa cared about.

Reiko waved away Toshi’s attempts at handing her the menu. “We’ll get the torafugu five-course meal. I’d get the eight-course one, but all my invitees refused to come.”

Toshi nodded and made his way to the curtain. Ayami had heard the order, but she listened as he repeated it. After, as she turned to walk deeper into the kitchen, she heard Reiko say, “I admit, I expected more of a fight to get in. That’s why I said to come early. Not that I have much else to do with my mornings now.”

Ayami’s hands curled into fists. Reiko had worked at a local onsen for nearly three decades, only to be dismissed at age fifty, as the resort ran out of reasons to exist. Reiko had accepted an early retirement. She was one of the lucky ones, with savings and a son who supported her.

Ayami forced her fists to unclench as she turned to the tank. Nine torafugu swam within. It had been ten yesterday. More shrinkage. Despite their best efforts, fish sometimes died before they could be served.

Ayami washed her hands and laid out her equipment: the cutting board, the knives reserved for cleaning fugu, the tray marked with “Dispose” for the parts she would cut away. She scooped the largest torafugu from the tank. It wiggled as she lifted it from the net, but before it could even attempt to inflate, Ayami inserted her knife into the top of its head.

The fugu stilled. Decades ago, when Ayami first started her training, many had questioned why. She should’ve felt as out of place as this fugu did, lying lifeless on a wooden cutting board. She hadn’t been born in a family of chefs, had never even eaten fugu in her childhood. She’d been an excellent student, had gone to university at age sixteen. Only to wind up in one of those glass-and-concrete offices: answering calls, filing documents, bringing tea to company execs.

She’d watched her fellow women shatter themselves on the shores of ambition. Passed up for promotion or settling for singledom. Bombarded with Japan’s declining birth rate and how it was their fault. Get married, have a child, find yourself bound by the shackles of motherhood. Unable to return to work, or returning to slashed pay, confused peers, and the label of an inadequate mother.

Ayami had said, No more. Not me.

She raised her knife. Now came the part she’d trained three years for. The part that required an examination where two-thirds of examinees failed, the part for which she was the last practicing chef in Shimonoseki—and indeed, the world.

Chop off the fins. Split the skin, peel it away. Remove the insides—liver, intestines, all filled with tetrodotoxin. She placed them on the “Dispose” tray. She worked quickly, with practiced ease. No part of fugu preparation surprised her now, not even those pollution-mutated fugu with their organs in the wrong places.

Perhaps it was good she had been born then, and not now. In that world of restriction, she had rejected corporate life and found the fugu.

She’d remade herself into something no one expected from her; in all her years growing up, she’d never heard of a female fugu chef—though now she knew they’d been there all along, and she wouldn’t label herself any sort of innovator, no matter what the magazines said. She’d drawn more than a few odd looks during her apprenticeship, sometimes studying alongside youths who’d worked in their parents’ kitchens their whole lives. But in the end: a license, a test. Standards that didn’t depend on drinking or socializing or singledom.

She’d passed the exam. She’d been that one third.

Ayami glanced down at the pale fugu flesh. Removing poison was just the first step. She had fugu-chiri to stew. Milt to grill and season. Sashimi to cut and arrange in the shape of a chrysanthemum. During Fugu Maekawa’s height, Ayami had three, four assistant chefs, though none of them were allowed to touch the fugu. Now she had just Keisuke, and he wouldn’t be in until noon.

Ayami smiled as she parted the torafugu flesh into thin, translucent sashimi slices. There had been golden years. Every table in Fugu Maekawa filled come dinner time. No one could get through the door except by reserving days in advance. Interviews with Ayami received full-page spreads in Shimonoseki Life, the city’s leading magazine at the time (now folded, not even digital). Gen, not so grumpy then, gave Japan Profile writers access to Fugu Maekawa’s kitchens and bragged about Ayami and the restaurant.

Eventually, the golden years ended. First came the non-toxic fugu, made by isolating the fish from tetrodotoxin-laden bacteria. Ayami closed the lid over the simmering stew and sighed. And we thought that would be the worst we’d face. Lobbyists asked the government to relax the ban on fugu liver, to relax the fugu preparation test itself. Shimonoseki sniffed in disdain, then raged, then panicked.

Ayami sprinkled seasoning over the milt. No, the problem had come with Synthfood, then Dreamscape. The former gave you the day’s nutrients in an easy-to-swallow packet, and the latter lets you enjoy the world’s delights in a virtual space. No calories, no accidents, no expensive plane tickets. The real world became obsolete. Virtual treks up Mount Fuji outnumbered real climbs many times over. Osaka Castle, built and rebuilt over centuries, stood empty in the height of summer, its continued maintenance a subject of budgetary debates. Shimonoseki’s aquarium closed last year, shipping as many fish as possible off to Okinawa.

Restaurants shut their doors. Some chefs jumped ship, worked with Dreamscape developers, opened virtual restaurants. Ayami, too, had offers, but she had no wish to leave Sushi Maekawa, and Gen had refused to even contemplate a virtual branch. “It’s not the same,” he’d said. “The Dreamscape, no matter how much it improves, can’t rival real life.”

But for most people, it seemed, the Dreamscape was better. And who could blame them, with the real world polluted and stifling and sunless? The falling demand made fugu—both traditional and non-poisonous— unprofitable to farm. The pollution in the seas made them difficult to catch. Ayami felt a prickle of pride knowing she’d outlasted them all, those safe-farmed fugu and their under- trained chefs.

There would always be people like Reiko and Minoru. The question was, would there be enough of them to support chefs like Ayami? The answer, ultimately, was no.

The first reporter—the first flesh-and-blood reporter, as drones had been buzzing around the building since morning—showed up at 1:30 p.m. Ayami allowed Keisuke to grill the shrimp while she sat down for her final interview.

He was a foreigner. Ayami wasn’t surprised. Since the restaurant’s golden years, western reporters had loved her, the office worker who became a fugu chef—a female fugu chef. She’d felt a vague unease when reading through machine translations of those articles; some of them seemed to treat her as a symbol more than a person. But today Ayami reserved her annoyance for those Japanese reporters who hadn’t come, who’d sent drones for the closing of the last fugu house.

“Do you mind if I turn on full Dreamscape recording?” the reporter asked. His Japanese was excellent, with only a hint of an accent.

“No,” Ayami said. She had little love for Dreamscape formats and interactive news, where viewers would be able to poke her virtually rendered skin, smell traces of cooking oil on her uniform. But if she refused, he’d create his report solely through memory reconstruction and that would be even more inaccurate.

He picked up a piece of fugu sashi with chopsticks, dipped it into the sauce, plopped it into his mouth, and chewed. A line of English text crawled across his multi-tab’s holographic screen. Notes to enhance his interactive video, probably. Maybe some stupid comment saying “tastes like chicken” or “doesn’t taste like anything at all, just the sauce” on the little opinion sidebar. How could a thirty-something foreigner understand things like texture and subtlety? At least he handled chopsticks well and didn’t drop the sashimi in the stew like one reporter had long ago.

Moments after the thoughts surfaced, Ayami pushed them down. She was not being fair to him. She didn’t know what he’d written, and he hadn’t done anything to earn her disdain— except to show up on this day when she was losing everything.

He ate more sashimi and drank a gulp of fugu-chiri. Then he said, “There is no tingling.”

Ayami raised an eyebrow. “What do you mean?”

He leaned closer as if to share a secret. “I’ve eaten fugu in the Dreamscape. It causes a tingling sensation to the lips. The virtual server said it’s to imitate the remaining traces of poison, and the tingling is part of fugu’s charm.” He frowned at his sashimi chrysanthemum and the petals he’d plucked away. “There’s no tingling in this one.”

Ayami chuckled. “No, no. Fugu—properly prepared fugu—isn’t supposed to cause obvious tingling. Some chefs add spice to the sauce which can create that effect, but as my old teacher used to say, too much tingle and you better run to the hospital.”

The reporter didn’t seem perturbed by this. Just drank more stew, moved on to the next question. “It must’ve hurt Maekawa Gen greatly,” he said, “to sell the building to a DreamHub developer.”

Ayami frowned, then tried her best approximation of a nonchalant shrug. “You’ll have to ask him about that.”

“He refused to speak to me and said I should direct all questions to you.”

In truth, Gen had wavered for weeks about the DreamHub developer’s offer. It felt like selling to the enemy. But Gen needed the money to care for his ailing father, and the restaurant had spent its last years losing money rather than making it.

Ayami said, “Gen accepted the best offer. That is all.”

The reporter tapped something on his screen. “There were many reports of your restaurant receiving offers to collaborate on a virtual branch. But Maekawa Gen turned them down. Is this something you wish had gone differently?”

Ayami mulled over what to share, then decided the truth would be fine. This was her final interview, the final record of her as Sushi Maekawa’s fugu chef. “It was Gen’s decision. But I… do agree with him.”

The reporter raised an eyebrow. “Oh? Are you distrustful of technology as well?”

“No. Not technology. It’s just… with Dreamscape…” She waved a hand, trying to explain, hoping she did not come across as outlandish to him as Gen sometimes seemed to the rest of them. “It’s not real. I’m not sure how I feel about it replacing the real world—and leaving people who haven’t given up on the real world with nowhere to go.” She thought of Reiko and Minoru, and of herself.

The reporter made another note. She expected him to probe further, but he moved on to a different topic, and for that she was grateful.

The interview continued until the reporter was about halfway through the carefully prepared meal. Then he told her he wouldn’t keep her any longer, and surely she had other customers to cook for.

“Thank you,” he said, rising to his feet and bowing, “for agreeing to this interview. I know this must be a hard day for you.”

Ayami returned his bow. “Thank you for coming. For… for being the only reporter who came.”

She’d turned away, about to walk back to the kitchen, when he said, “Please, don’t think too badly of my fellow reporters. The JAXA conference is running through the week. That’s probably why they couldn’t show up in person today.”

Ayami paused in her steps, contemplated what to say, managed to find nothing suitable. She resumed walking. She had to get back to the kitchen. She trusted Keisuke, but she didn’t want to spend another minute out in the dining area.

Toshi was gone when Ayami returned to the kitchen. Left at 2:00 p.m. sharp after Sumire arrived for her shift. “He said it looked like we didn’t need him,” Gen explained. “Of course, I offered to pay him for the whole day, but he would have none of it.”

Ayami didn’t reply, just continued turning over the grilled eel. Gen lingered for a moment, then stepped through the partition back into the dining area.

“He didn’t even say goodbye to you,” Keisuke said as he stretched a shrimp for tempura, voicing Ayami’s thoughts.

“It’s alright,” Ayami said. “It’s… characteristic of Toshi. Professional until the end.”

“More like ice-cold and heartless.”

Ayami’s mouth quirked into a smile. “Well, at least we won’t have to worry about Toshi surviving this cold and heartless world. The rest of us will have only Dreamscape to fall back on.”

“Dreamscape? Ha. If any of us gets lost in there, Gen will hunt us down and give us a good beating.”

He glanced at the partition as if wondering whether Gen would return to do just that, then said more softly, “That’s for the rest of us, of course. You’ve earned a break, and even Gen can’t dispute that.”

The partition flapped open, but it was Sumire who stepped through, not Gen. Ayami passed the completed eel dish to her, then said to Keisuke, “I’m not sure I’m ready to… to retire. To live only in Dreamscape.” She didn’t want her last memory of her working life to be failure, to be her restaurant shutting down.

As Sumire left, Keisuke said, “Gen has a point, and I completely understand why he feels that way. But sometimes… I wonder if they might have a point too.”

“They?”

He glanced at her. “I was reading some articles this morning. About this place, and how we’re about to close. Most of them were the usual—lamenting the loss, rehashing your story, talking about the sale to a DreamHub developer. But there was one that said… it said we were part of the problem.”

Ayami had an inkling about what he was talking about, but still she said, “Please explain.”

“Part of what caused that.” He waved a hand at the window behind him. “The poison in the air, the poison in the seas. The fishing industry was at least partially responsible.” He sighed and dipped the shrimp into batter. “It got me thinking, maybe Dreamscape is the way out. If we did all that to the real world, then we should get out of it.”

He’d forgotten to pre-heat the oil. Ayami had half a mind to point that out but stopped herself. “But will hiding in Dreamscape really help? If we want to fix this, don’t we need to be, well, here?”

Keisuke shook his head. “Probably. I don’t know. My point is, it might be worth looking at from another angle. The Dreamscape isn’t your enemy. You’ve been working hard all your life. Sometimes it’s okay to just stop.”

Just stop. Step into an early retirement, like the one forced upon Reiko. Except unlike Reiko, Ayami had no one. No family to rely on, no close friends unless she counted Gen. She had poured her life into her work, only to find herself standing at the pinnacle of a dying profession.

During the three o’clock lull, Sumire walked over to Ayami as she was inspecting the knives. “I sent something to you,” Sumire said. “Check your multi-tab.”

Ayami tapped the mailbox on the hologram and found a pamphlet from JAXA, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency. It listed training programs for mechanics, navigators, onboard nutritionists . . .

“And?” Ayami said. Then regretted it, when Sumire’s face fell.

“I thought . . . I thought you’d be interested.” Ayami frowned. “Interested? As in . . . ?”

“To apply. You understand cooking and nutrition, and you’re good with your hands. I figured, even JAXA could use someone like you.”

Ayami wanted to laugh—but at the same time, felt something close to tears pricking the back of her eyes. She didn’t know whether to read this as a joke or to be touched Sumire genuinely thought so highly of her. “I’m old. Even if JAXA needed someone, they’d want someone young. Someone like you.”

Sumire bit her lip. “I heard you earlier, when you said you weren’t ready to retire. I heard your interview with the reporter too. You said you wished there was still room for people who haven’t given up on the real world. Isn’t that what JAXA is trying to do? To carve new roads for us, not in Dreamscape but in space? I’m probably not smart enough to help, but you—”

“Don’t say that,” Ayami cut in. “You’re plenty smart. If you think whatever JAXA is doing could work, then you should apply.”

Sumire’s smile was brighter than the overhead lights, brighter than the sun in Ayami’s memory. “Thank you. Maybe I should be more confident. But in turn, I think you should also be more positive. It’s never too late. Please think about it.”

They’d meant to shut down at 10:00 p.m., but the last customer lingered, drinking sake and eating his fifth tuna temaki. Ayami, Gen, Sumire, and Keisuke let him be. Ayami scooped out the last torafugu in the back and started preparing it. The three in the front swam on, uneaten.

“Making this one for you,” Ayami said to the three remaining employees. “At this rate, we’ll be done before the customer out front is. You want me to grab the fugu from the front tank too?”

A chorus of no’s echoed around the kitchen. “Just one piece is enough for me,” Sumire said.

“I’ve had enough fugu to last a lifetime,” Gen said. “And you still don’t make it good as Father did.” Ayami rolled her eyes, and he chuckled.

“Not sure if I should trust you, Ayami,” Keisuke said. “Maybe you’re going to poison me for the time I burned the calamari.”

They all laughed, and chatted, and promised to keep in touch, though Ayami had no idea how many of those promises would be kept. She liked them all, even Toshi, but memories of Sushi Maekawa would become a wound now, and keeping in touch with her co-workers would feel like scraping at the scabs. However, for tonight they were a family, complimenting her on the fugu meal with vocabulary the reporter would never have, cleaning up together on their last night, Gen himself sweeping and taking out garbage.

Gen would return. There were still inspectors to meet, deals to sign, further clean- up to oversee. But for the rest of them, this was the last time.

The last customer left with a ring of the old metal bell. Ayami leaned against one of the wood tables and stared at the tank on the counter.

Gen walked up to her and slowly removed his sunglasses. He blinked as if trying to clear away dust or tears.

“Maybe . . .” Ayami began.

“Hmm?”

Ayami bit her tongue. Maybe you should see someone about your eyes, she wanted to say. But she’d already voiced those concerns a dozen times, and Gen always brushed her off.

Instead, she gestured at the three remaining torafugu. “Such a shame to throw them out.”

“What do you propose?”

She couldn’t keep them. She still lived in the single-room flat she’d had since her office worker days; she didn’t need anything bigger since she spent most of her life in Sushi Maekawa. She wouldn’t be able to keep torafugu alive for long. And she didn’t want to stare at them all day, didn’t want to be reminded of the life she’d lost.

“I’ll need a container,” she said. “And rope.”

They found a clear plastic container with a lid and a length of yellow rope. Ayami scooped water and fugu from the tank to the container, and Gen poked holes in the lid to allow air to pass through. Ayami bound the rope around the container and tied a handle at the top.

At the door, Ayami bowed to Gen. “Thank you for everything.”

He shook his head. “No, I should thank you. I have barely a quarter of my father’s culinary talent. It’s thanks to you that Fugu Maekawa survived so long.”

Ayami didn’t miss how he’d used the restaurant’s former name. “It’s thanks to you, too. A restaurant is more than its chef.”

The corners of Gen’s mouth curled upward. “We outlasted all of them, didn’t we? Take care, Ayami. You were the best there was.”

She hefted her backpack and the container of fugu. “Take care, Gen.”

The walk to the bus stop seemed to take twice as long as usual. Her multi-tab said the next bus would arrive in twenty minutes— decent, considering how late it was and how much public transport had downsized. The bus arrived, carrying only two other passengers: a woman and a man sitting side by side. They gawked at Ayami and the fugu visible through the container. The woman whispered a string of words to her companion and gesticulated so fervently that Ayami wondered if she recognized her. The woman looked old enough to have read Shimonoseki Life back in the day.

Ayami got off at the Kanmon Wharf. It was a short walk to the harbor, the container in her right hand, the fugu staring out into the night, as uncertain as Ayami herself. Even if the city lights blinked out, the skies were no longer clear enough for anyone to see stars. Her steps tapped a steady rhythm on the wooden walkway. She could see the abandoned aquarium building. Once she could’ve asked them to take the torafugu, but now that wasn’t possible.

Ayami knelt on the empty pier, placed the container beside her, and after a moment’s hesitation, released the fugu into the Kanmon Straits.

They would probably die out there. Most things did these days, out on the tainted waters. But maybe they’d survive. They’d survived this long, from their trip to the restaurant and now back to the sea.

Ayami returned to the bus stop and flicked on her multi-tab. She tapped the mailbox icon and opened the JAXA pamphlet.

The land and sea these days were not made for her any more than they were made for the fugu. But maybe she too could find livable waters. She read and reread the registration dates, locking them away in her mind. She’d made change work before, when her life and career had been tumbling toward dead ends. Sumire was right. Maybe it wasn’t too late.