Head of the Household

In preparation for her marriage to Koschei the Deathless, the mortal Ira is eating. She is reading about dental procedures that sharpen the patients’ teeth to vampiric points. She is studying videos of pythons in the Florida Everglades unhinging their jaws. She is imagining how the smooth shell of a Great Blue Heron egg would feel against the concave of her tongue.

Most of the married women she knows turned themselves into beanpoles. No, worse: they turned themselves into matchsticks. They filled their fridges with sugar-free jam and flavorless cottage cheese, and they ran up and down and up and down the stairs of their apartments, and they stood in front of their mirrors tapping at their ribs as if they were the keys of a xylophone. But not Ira. She eats six meals a day and as many each night. She’ll eat the whole world if she must.

The wedding is set to take place in five months’ time on the southern shore of Keuka Lake, minutes from where Ira lives with her parents. Of the eleven Finger Lakes, Keuka sits right at the center, and Ira’s dad likes to joke that it’s like their town is giving all of mankind the bird. It’s a wholly American thing, Ira’s mom says, rolling her eyes at her husband: this us-and-them mentality and the middle finger. In Vladivostok, where they’re from, if you want to give somebody a piece of your mind, you stick your thumb through your fist and shake. The middle finger is nothing. It’s used simply, innocently, to point.

Two weeks after moving there, Ira’s dad bought a shirt from one of the downtown gift shops with “Hammondsport Versus Everybody” printed against a forest green background. Fifteen years later, it’s his lounge-around-the-house-yardwork-car-repair favorite, and Ira’s mom scrunches her nose every time she sees him wear it. They have their ESL worksheet wars about it. He says, c’mon, sourpuss, you can’t spell “assimilation” without “elation.” She says, you know what, Tyoma? You can’t spell “assimilation” without “ass.”

Ira explained all this to Koschei on their first date, which was not so much a date as an in-blood marriage contract signing, and now Koschei thinks that’s what Ira’s town is called— not Hammondsport, but Hammondsport Versus Everybody. And why not? Mortals have done stranger things. There’s a village in the Kemerovo Region whose name means “Old Worms.” Another one outside Ryazan that translates to “Kind Bees.”

Despite being a petrifier of kingdoms and an abductor of princesses and an overall not- particularly-reasonable guy, Koschei has agreed to have the wedding in Hammondsport Versus Everybody in the interest of convenience for the bride’s immediate family. The logic being that, even with the recent visa trouble, Koschei’s side will have an easier time getting to Keuka Lake, USA, than Ira and company would to Koschei’s mansion in Rublevka. After all, Koschei’s guest list consists of powerful sorcerers and minor gods, while Ira’s grandmother—who followed her son to the States and now lives across from the Finger Lakes’ premier producer of ice wine— has terrible blood circulation and swears the next time she gets on a plane her legs will swell up like boiled sausages and finally burst.

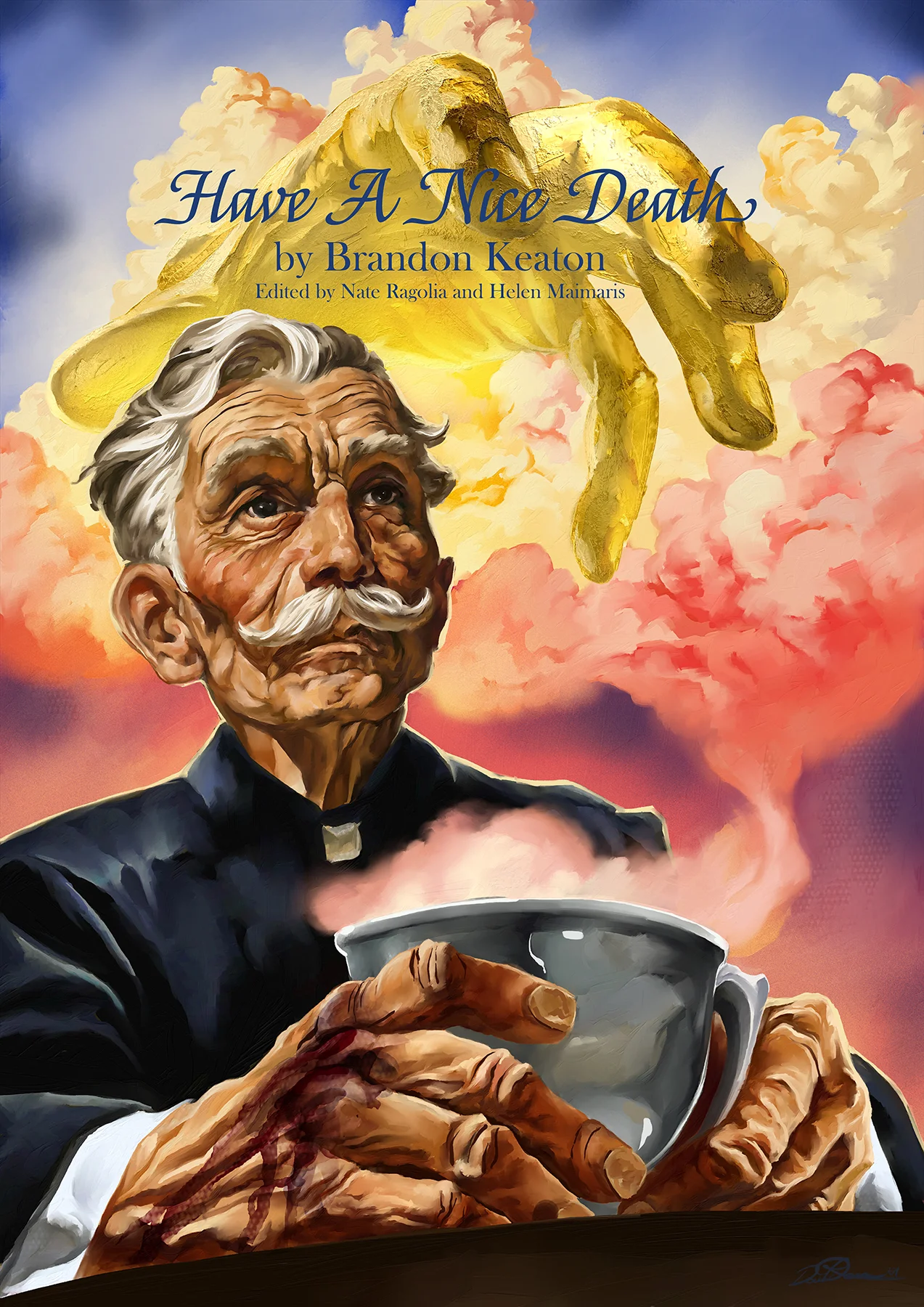

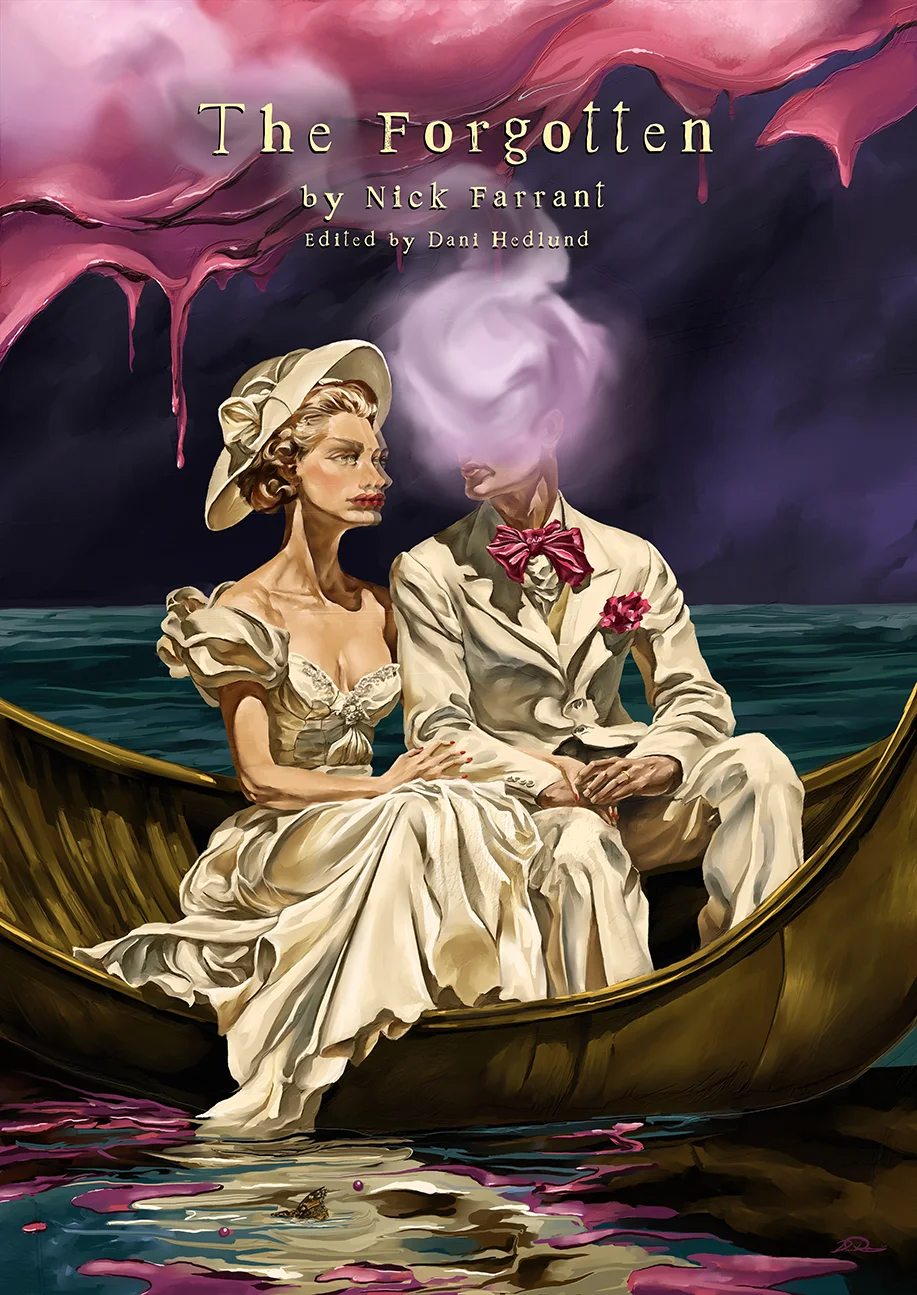

So, it’s a busy time for all. Ira’s dad is building the ceremonial arch and Ira’s mom is searching for a tasteful mother-of-the-bride dress that’ll fit with the wedding’s pastel color palette. Koschei is getting his suit tailored between prior business commitments, which include dismembering heroes, shoving their limbless bodies into wooden barrels, and casting them out to sea. The suit is a color he hasn’t worn before in all the times he’s been married. A lovely muted pistachio. Perfect for spring in upstate New York.

As for Ira? She is eating.

Nareznoy Baton

Wheat loaf with crunchy crust decorated with large notches. Typically used to make buterbrod.

Not that Ira needs a reason to eat beyond being a mortal and mortals requiring it, but if you must know, she is eating now, in such impressive quantities, to prepare for the wedding tradition of khleb y sol. Toward the end of the ceremony, after the speech about life’s many obstacles and before the single chaste kiss, someone brings out a round loaf of karavay bread and a shallow bowl of salt. The salt represents the gift of something precious, and the bread—well, the bread’s the heart of the matter. Because once the couple is presented with the loaf, each party is told to take the biggest bite they can. Big as a wolf ’s bite, the officiant says, a boar’s bite. Big as a tiger’s bite, a bear’s bite.

And the one who takes the bigger bite is declared the head of the household.

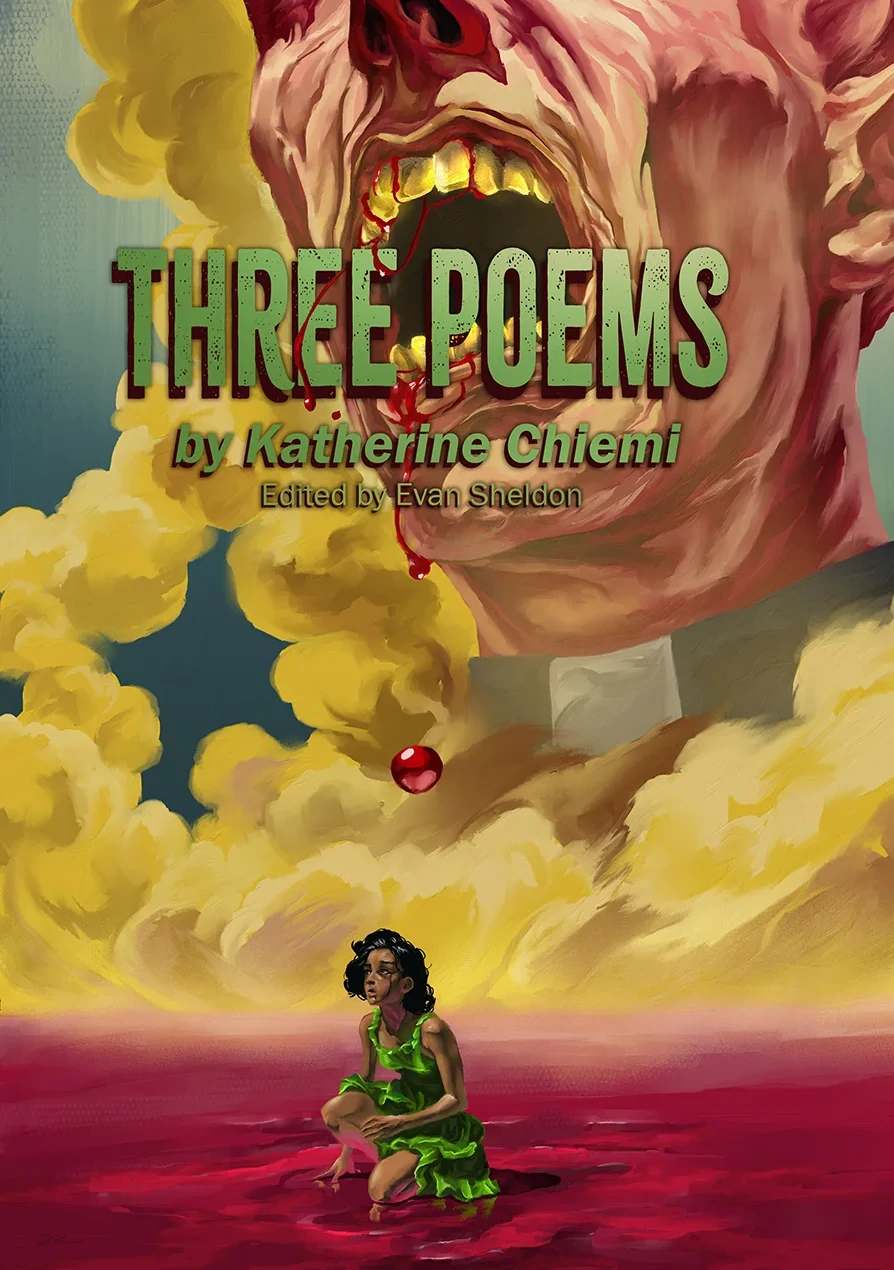

Which is a dangerous thing to allow Koschei the Deathless to become, on top of all he already is: ruthless and brutish, egomaniacal and immortal at that. With hideous tusks he can bare at will and a seven-legged horse that’s the fastest in all the land and will take no other rider. Koschei the Deathless, with twelve wives locked in the basement of his Rublevka mansion and twelve more in the wine cellar of his dacha out east. And those are just the ones the average person has heard whispers about.

Among them is Ira’s best friend, Alice.

As she does her cheek-stretching exercises each morning, Ira remembers Alice. Alice, whose family immigrated a couple years before Ira’s and lived in Hammondsport only briefly before moving to New York City. Alice, who introduced Ira to tankinis and emo rock when they were kids and later invited Ira for weekends at her leaning walkup in Brooklyn. Who said their parents’ old-country superstitions were stupid: of course single people could sit at the corners of the table at Alice’s Friendsgiving dinner, and of course she would hug Ira right over the doorway if she damn well pleased.

Ira hooks two fingers in either corner of her mouth and pulls. She thinks about the brown pelican’s throat pouch, the way it’s basically a big to-go bag for fish. She opens her own mouth wide, wide, wide until her jaw pops and the skin of her lip splits. To make room, she drops her tongue to the floor of her mouth and reminds herself why she is doing all of this in the first place.

Koschei may be a god in some circles, but tradition is the one god everyone knows.

When she takes the bigger bite, she will become the head of the household.

When she becomes the head of the household, she will set them all free.

Ira waits until her parents have gone—her dad to the hardware store to pick up additional lumber, her mom to the salon to consult with a hairstylist about low-maintenance updos—then makes her way to the pantry. She steps carefully around the jars of pickles and the tins of fancy meringues, the boxes of Corn Flakes, and the bags of sushki her mom brought back the last time she went to the city. Then Ira uses her foot to nudge a fifty-pound bag of pilaf rice, which slouches forward to reveal the hammered-out space in the wall where she has been storing her training bread.

Ira has never seen a khleb y sol ceremony before, so she figures to be prepared, she’d better practice with every possible kind of bread she can find. Nareznoy baton was the easiest to get hold of. She bought a dozen loaves at once from the Eastern European specialty store the next town over, thinking it less risky than taking multiple trips, and by now the last of them is dry and stale and completely sapped of its once warm, grainy aroma. She rolls back the paper sleeve. The crust is thick as the mortar between bricks and has lost all its gloss. This one’s going to hurt, she can tell.

She swallows hard, rolls the sleeve back once more, and opens wide until she feels something in the vicinity of her throat give. Then she drives her teeth down like a spade to the earth. Too bad for her, the earth drives back.

The hard crust cuts into her gums. Blood rushes up to meet it as she takes a bite.

Zavarnoy

Black rye bread originating in monasteries. Made with zavarka brew and malt, which give it an unusual sour-sweet taste.

After finishing the weeks-old nareznoy loaves, Ira’s gums are red and swollen and dipping into the spaces between her teeth, but she can’t afford to take time off now. Her record for a single bite is only a sixth of a loaf—two or three inches at most—and she’ll have to do a lot better than that if she’s going to beat Koschei, who has been eating for six centuries, though never out of necessity but frequently out of indulgence or demonstrations of power, or spite. He has valets whose sole job is to lift the mustache off his lips, and others to move aside his ten-foot-long white beard so it doesn’t catch crumbs. The one time Ira saw this happen was at the banquet following the in-blood marriage contract signing. It reminded her of a fleet of bridesmaids holding a trailing veil.

Though Ira can’t afford to take time away from her training, she figures she can at least be strategic about it. So, when it’s time to restock her secret stash, she opts for zavarnoy.

She gets it from the same Euro market as before, but this time special orders it. The owner explains the Vasilievs of Watkins Glen had their annual family reunion last weekend and totally cleared her out of the black ryes. When the next batch comes in, Ira can see why: there’s the tender crumb and the gentle tanginess, and the owner confirms what Ira has heard about this bread staying fresh and soft longer than most. The loaves are squatter than the nareznoy, their tops lightly scored and dusted with flour. Ira is in the pantry trying to suss out the best angle from which to approach them when the bridal attendants arrive.

“Hello, hello!” they call through the window. Ira’s mom and dad are at the dance studio taking ballroom lessons for the customary first dances. She shoves the zavarnoy into the hole in the pantry wall, replaces the enormous bag of rice, and hurries to answer the door.

“Hello!” the attendants sing in unison. “Hello, hello!” Five of them, with red hair, yellow hair, black hair, chestnut hair slung in a low ponytail, white hair arranged in a pert chignon. One has delicate freckles, another thick, strong- looking ankles. They wear matching navy blazers and the same expression: one of unflagging, almost frantic enthusiasm about Ira’s upcoming nuptials, cut with fear and gratitude that it isn’t them. Their eyes remind Ira of squirrels’ eyes. Not the lazy, well-fed squirrels who are socialized to people and hang around the dumpsters behind the restaurants downtown. The ones who live in the forest. Who remember they’re still meat beneath all that fur.

“Hello—” Ira replies. They look at her expectantly, faces frozen. “—hel… lo?” she finishes. They break into broad grins and nod.

She waves them into the house, remembering the terms of the contract: One hundred days in advance of the wedding, the bride will be assigned several attendants, no fewer than three and not exceeding six, to assist with wedding preparations including but not limited to: vendor negotiations and bookings, creation and execution of design scheme, dress selection and alterations…

Ira notices the flour dust on her hands and quickly wipes it off on the back of her jeans. “Thanks for, uh, being here. I’m Ira. What are your names?”

The attendants smile brightly. “Names?” one repeats, confused. “Names… names?” another agrees.

They scramble past her, circling the dining room and dropping binders onto the table with loud clonks and tucking number two pencils and plastic rulers and various shades of off-white lace trim behind their ears.

“Oatmeal or eggshell?” Freckles asks.

“Ivory keys or pale dove?” Chignon wants to know. She glances at the flour on Ira’s jeans. “Snow white or white snow?”

Ira feels the bubbles of exasperation gathering at the backs of her eyes and blinks them away. Even though she doesn’t care about any of this, even though lace color was the furthest thing from her mind when she put herself in Koschei’s path at the stables in the Catskills where she’d heard, before the recent visa trouble, he kept his horse while in the States, she knows it’s part of it. The khleb y sol ceremony is her ticket to getting Alice back. And her ticket to the khleb y sol ceremony is the most old- school wedding she and her team of grinning attendants can dream up.

That’s where the fates of the other women fell apart. They got sucked in by Koschei’s dark, heavily lidded eyes, the way he murmured softlyprincessa, princessa during the proposal, which wasn’t so much a proposal as a command, for afterwards he threatened to turn them into deaf adders and their family members into field mice if they refused him. They got sucked in by the gold rings and velvet cloaks, the promise of endless sums of money for college tuition and medical bills, the way Koschei’s skin looked so youthful, so supple, so long as they didn’t get close enough to see the places where it cracks and peels. Once Koschei takes a shine to you, you’re done for. The word “choice” in every language cartwheels right out of your vocabulary.

They got sucked in then and again at every stage of the wedding planning, for all of them wanted one of those modern affairs you see in the magazines: chic designer dresses, bouquets of daisies, deejayed receptions in brick-walled industrial warehouses following no-nonsense ten-minute ceremonies at city hall. No one wanted to wear the shapeless sarafan or the single chunky braid. No one wanted to hear the “lyulee, lyulee” of the traditional folk song as they walked down the aisle, trying to keep their heads steady so as not to let fall the kokoshnik, with the beaded forehead drapery that looked like something everyone’s babushka would say was just darling.

No one wanted the kind of wedding in which an outdated head-of-the-household-setting ceremony would feel perfectly germane.

But Ira does.

At the table with the attendants, she thinks about the zavarnoy in the pantry and fakes a close-mouthed yawn, testing how wide she can take it without parting her lips. Chignon peers her way quizzically.

“Okay, okay?” she asks, eyes narrow.

Ira deflates her cheeks and smiles. “Okay, okay,” she returns.

The attendants Koschei sent may not be locked away in his cosmopolitan mansion or in his dacha nestled in Siberian spruce, but Ira makes a mental note to free them, too.

Kalach

Twisted white bread in the shape of a kettlebell, one side significantly thicker (“the belly”) and the other side much thinner (“the handle”). Originally popular among workers who, by holding the handle, could eat the bread without washing their hands. Afterwards, the handle was thrown away or given to the poor.

Koschei the Deathless is having a hell of a time trying to get a visa. Since relations between the two countries went sour—not zavarnoy sour, which is balanced with a bready sweetness, but sour sour, like an all-grapefruit wedding diet— the consulates on both sides are turning nearly everyone away. Koschei himself has been shuffled from line to line, from waiting area to waiting area, from one smudged, sign-taped window to the next. The embassy didn’t even bother to arrange special lines for Koschei, so he’s stuck in the same ones the office workers and old grannies use. Apparently, during one particularly painful visit, he vowed to turn the clerk into a Fischer’s clawed salamander if he didn’t get his papers that day. But the clerk only stared at him blankly and smacked her gum—whoosh, pop!—until Koschei threw his hands up in frustration and marched back out the door.

Koschei is a god in some circles, and a menacing one, to be sure. But consular law is the one god everyone cowers before.

Now he’s been asked to provide documentation that proves his intent to return after the wedding; a consular officer will refuse the visa application of anyone deemed a potential flight risk. Koschei tried to explain that he’s lived for more than six hundred years, through wars and famines, princely feuds and peasant uprisings, nuclear disasters and deadly snowstorms and vicious counterrevolutionary campaigns. When one of his valets muttered under his breath that Koschei had caused most of these, hadn’t he?, Koschei drew his shashka from its scabbard and pierced the idiot through the groin. He requested a replacement valet with a modicum of sense and exceptionally neat handwriting, and said valet is now hard at work compiling proof of Koschei’s ties to his homeland.

Which include a great deal of property, for one thing. The luxury estate in Rublevka with fifteen balconies and a circular drive, the riverside dacha done in the Italianate style—each with their own gallery dedicated to the avant-garde masters—and waiting for him there, twenty-fourliving wives and many others besides. Et cetera.

“Et cetera, et cetera,” Freckles chimes. Ira wonders if everything bears repeating.

While Koschei works to secure passage to the wedding, Ira keeps eating. She goes through every loaf of bread in the pantry, all the time making her bites bigger and bigger, and during appointments with the wedding vendors, she continues her training. At cake tastings, at dinners to sample different catering menus, she stretches her lips into an elastic “O,” makes of her mouth a black, wet hollow. She downs a three-tier cutting cake in a single bite. One day, practicing in the pantry with a kalach, holding it by its thinner side, she surprises herself when she reaches her teeth all the way past the bread’s belly, all the way past its handle, and champs down full force into the skin of her right pointer finger.

“Eeee!” she cries. But the mouthful of bread stifles her scream, so the attendants, who have arrived early to finalize decorations, do not notice. With the possible exception of Chignon—who, hair swept off her ears, has always had the best hearing—the attendants hear from their place on the doorstep only the sound of an excited bride-to-be singing her procession song: lyulee, lyuleeee…

As a natural side effect of her quest to free the captive brides of Koschei the Deathless, Ira has become gigantic. Maggie Sherwood, Hammondsport’s top-rated seamstress, has cleared her appointment books for the entire season to make space for Ira’s near-constant alterations. With six weeks to go, she has let the dress out so many times, and her arthritis has flared up so badly, that she swears after this wedding that she’s cooked, she’s through, she’s done. The attendants arrange for yard after yard of the finest silks and satins to be flown in from the Caucasus—on Koschei’s dime—and with the exception of poor Maggie’s engorged knuckles, Ira doesn’t feel a bit sorry. The bigger she gets, the better prepared; the better prepared, the more likely to win. To bring home Alice, who taught her how to turn a cupcake into a sandwich by breaking the base in half, and who never believed in superstitions or bad luck, even when it met her at the top of the aisle.

As for Koschei? He doesn’t notice any change in Ira’s appearance. The attendants send him pictures of her from time to time, wearing this ceremonial headscarf or that lacy shawl, and always he replies that she looks delicious in everything—only would they make sure that whatever she ends up wearing matches his new pistachio suit?

As far as he’s concerned, most mortal women look more or less the same. He remembers liking Ira’s left earlobe, the way she fingered it that day at the stables when she appeared with a pocketful of carrots and asked his horse’s name. Koschei himself hasn’t had earlobes in years.

Which is not to say that Koschei the Deathless is the accepting sort, or that he looks past the external because it’s what’s inside that counts. Only that every mortal woman he’s ever met looks the same with her limbs bent and fastened, her fingers bleeding and nailless, her tongue lapping at the moisture that comes up from the stone floor after the rain, sometimes, if she’s lucky. All knotted, bleating creatures in the dark.

Borodinskiy

Dense sourdough rye sweetened with molasses and flavored with coriander and caraway seeds. Legend has it the bread was first baked in a convent established by a widow of the Napoleonic Wars, who built it on the site of a former battlefield to honor her dead husband and topped the loaves with coriander seeds to represent grapeshot. Others say a composer-chemist brought the recipe from Italy.

It is one month until the wedding and the frenzy over the impending nuptials seems to have consumed Hammondsport completely. Ira’s dad is at the gift shop getting shirts custom-printed for party favors—“Koschei and Ira Versus Everybody”—and her mom has borrowed the attendants for a round of interviews with potential flower girls. Ira has a young cousin coming in from northern Pennsylvania, but Ira’s mom won’t hear it, citing the four-year-old’s wobbly walk and terrifying grip strength. “Goodness, don’t you remember the deviled egg incident last Christmas? She’ll grind those rose petals to smithereens if we let her!”

Koschei may be a mighty sorcerer, but nothing traps mortals under its spell quite like the pressure to plan the perfect wedding.

Ira lines up three of the small, thin-crusted borodinskiy loaves on the counter. She drops her jaw and pushes them in one by one, closing her lips around the heel of the last. Her mouth floods with sweetness and spice and she works her teeth furiously, gagging a little each time a half-chewed clump hits the back of her throat.

The Napoleonic Wars. The traveling chemist. Everyone has their favorite version of the story, but the true origins of borodinskiy bread remain a mystery. Like so many things, really. Like what Alice is doing right now. What did Koschei do to mesmerize her that day they met in Williamsburg’s Domino Park? Did he fill her head with pictures of a free ride to her dream design school? Pictures of her brother returning from his deployment safe and whole? Ira saw Alice only once after her friend signed her own in-blood marriage contract. Alice looked good, happy. She was gushing about mermaid skirt silhouettes and DIY donut bars. She asked Ira to be her maid of honor, then Ira never heard from her again.

She’s alive, though. She’s alive.

Another mystery is what Ira will do once she’s declared the head of the household and has freed all the women under Koschei’s lock and key. She figures she doesn’t get to just step down after that. She’s signing herself up for a lifetime of cleaning up messes—a lifetime that, depending how this plays out, may never, ever, ever, ever end. She could extinguish every thought of bloodlust, calm his every brewing storm. She could throw him into the same dank basement where he kept the women, let the cockroaches burrow into his immense white beard, lay their eggs.

What would be best, Ira knows, would be for her to change his name: to do away with the “Deathless” part that seems to be the root of so many of their problems. To do that she’ll have to find his soul, which is kept apart from his body, as naturally a soul would have to be for its body to perform the cruelties his body does. One morning, over hot tea and seating charts, Ira brings up the matter of Koschei’s soul to the attendants using a tone she hopes reads as casual, well-meaning—a wife concerned only for her husband’s health.

“Why, yes,” chirps the red-haired attendant. “As far as any of us know, it’s still inside the needle inside the egg.”

“Inside the needle inside the egg?” Chignon asks. Red confirms, “Inside the egg inside the duck.” “And the duck’s inside the hare?” Freckles probes. “The duck’s inside the hare.”

“And the hare, that’s still inside the chest?” picks up the breathless one with yellow hair.

“The hare’s inside the chest. Yes, yes.”

“And the chest, that’s buried—”

Ira uses her thumbs to rub her temples and her middle fingers to rub her forehead where the gnarl of impatience is starting to build up. “Ladies!” she interrupts, waving the seating chart at them. They turn to her, beaming. “Can we put Volos and Marena at the same table, or are they still arguing over—what did you say it was? The artistic integrity of The Rite of Spring?”

Karavay

Round yeast sweetbread traditionally baked for weddings. Richly decorated with a wheat-ear-shaped wreath symbolizing prosperity and interlaced rings symbolizing faithfulness.

In the weeks leading up to the wedding, Koschei finally gets his visa. One of his valets identifies a loophole: a particularly impressionable officer at the consulate general in Uzbekistan, a young man—a boy, really—who finds himself alone one day after his colleagues are struck down with a sudden bad case of lice, and who, once alone, proves quite amenable to Koschei’s brand of bribery.

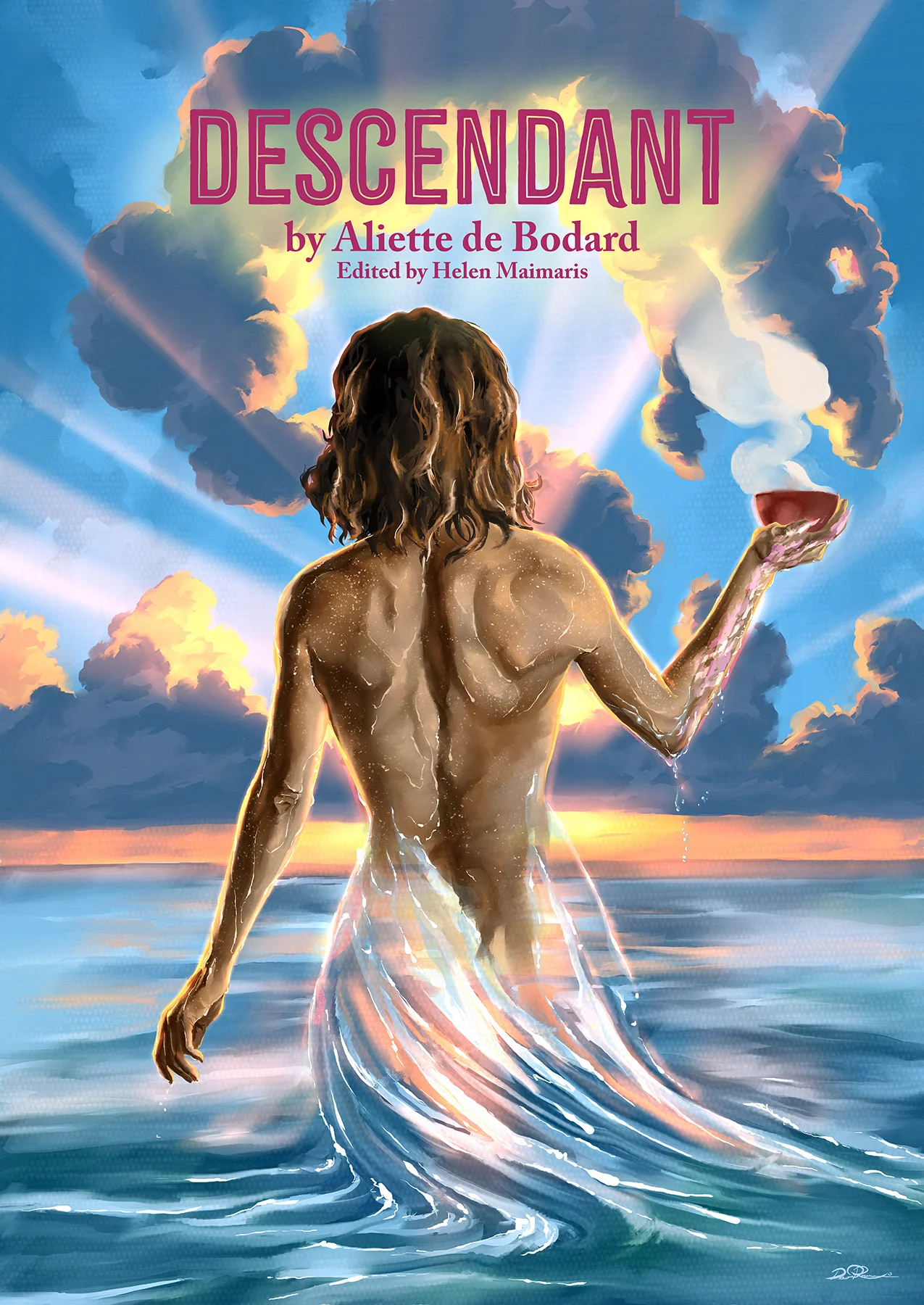

In the days leading up to the wedding, Ira outgrows everything. Old Maggie Sherwood is at her hip with shaking hands and a threaded needle right up until the last minute. At the final fitting, Ira is magnificent: sleeves cinched with ribbons at the wrist, her great neck stacked with pendants and pearls, embroidered red fabric billowing in the May breeze like a grand parade float. She has done all she can to prepare herself. She is almost ready.

The morning of the wedding, Ira installs knives behind her teeth. It is an added precaution: she would hate to get so much of the karavay into her mouth only to find herself unable to bite clear through. She makes them out of a serrated metal strip she found at the hardware store the previous night, when the owner dipped his chin approvingly and called it a spectacular choice for jewelry making, setting delicate stones and enamel cabochons and the like. Then he raised one bushy brow at Ira and said, wait, surely she’s not setting her own stone, meaning the stone inthe ring for tomorrow? Ira laughed nervously, but before she could come up with an excuse, he was already talking about the ceremonial arch her dad had constructed, going on and on about how he’d picked a sturdy kiln-dried cedar and even sprung for the combo stain and sealant, which was practically mandatory by the water—a smart man, her father—and she was out the door.

So: Koschei proudly debuting his muted pistachio suit. The giant Ira with her single braid, shaking the lake stones loose as she walks the narrow clearing between the rows of folding chairs. The hired flower girl standing prettily to the left of the arch, not fidgeting one bit. A stranger in sunglasses playing the treshchotka, and God of Night Chernobog crying because the music reminds him of his childhood. God of Fire Dazhbog crying because he can’t help it: he’s drunk and when he’s drunk, he cries any time someone else starts with the waterworks. Svarozhits, also a god, someone’s annoying nephew, crying and making the worn-out joke that, hey, it’s a moving service, and he is only human.

Maggie Sherwood in the back clutching her swollen hands and sobbing. Ira’s parents in the front wiping away happy tears—that is, crying for all the wrong reasons.

Ira and Koschei join hands in front of the arch. On the far side of the aisle, he looked so striking, his beard groomed slick and skin radiant in the late afternoon sun. Up close, though, the dense layer of cosmetics threatens to slide down his face in patches, revealing a millimeter here, a millimeter there of skin like crinkled rice paper, like snakeskin left behind and coated lightly with radioactive ash.

Some words are said. Some more. Et cetera, et cetera. A reverberant moo comes from the gift table. Volos, God of the Underworld and Livestock, has brought a kalmyk bull from the steppe, a bow taped to the amber coat between its short, high horns. It snuffles at the gift boxes, hot and restless.

Finally, they wheel out the karavay.

It’s like nothing Ira has seen before. It takes all her attendants, plus all of Koschei’s valets, plus the hardware store owner and his three strapping sons, to steer the dolly straight. On it, pitched sideways, is the wedding loaf: at least five feet across, golden brown and adorned with the requisite wreath and rings, carved stars as wide as Ira’s hands, sculpted rosettes bigger than the flowers in her bouquet. The guests cheer. The strapping sons sweat. Ira gasps and one of the metal teeth nicks the inside of her cheek. Following the karavay in the processional, a boy she doesn’t recognize carries a box of salt with the approximate proportions of a midsize aquarium.

The officiant nods at the salt, indicating the pair of them should each take a pinch. “May your life together never be bland.” Koschei smiles, baring putty-soft, rotten brown teeth between curved tusks tipped in gold leaf for the occasion. His nature prevents him from truly caring for any of his brides, but he has always been one for ceremony.

The bread carriers heave the massive karavay onto their shoulders and kneel before the couple. Koschei waves for Ira to go first. In his ghastly voice, each syllable a death rattle, he says, “Go on, princessa. I have all the time in the world.”

Every eye upon her, she remembers all she’s practiced: square loaves and round, rye breads and white. She is so full. From months of high-performance eating, yes, but also with memories of Alice: those she can call forth solidly from the past, and those future memories Koschei would rob her of, which she senses only as wisps now—something dormant never to grow. These have more weight than anything. The heavy substance, heavier absence swirl together in her maw and in her belly and they push against the walls of both, which stretch and thin until they’re nearly translucent.

On the fringes, there is something else. Something with the flavor of doubt. How well can her preparation—the training of her mortal body, the scheming of her mortal mind—hold up against a god as fearsome as this? Ira was never the brave one. Since they were kids, Alice was the bolder of the two, the one who marched out in front toward all of their adventures. Will Ira only follow her again now, into that dungeon, another captive crushed under Koschei’s forever spell?

Ira shakes her head free of this. There is no room for doubt. Truer, there is no time.

Nobody likes an overly long ceremony.

She takes a moment to collect herself, then a deep breath, then a bite.

And crams the entire loaf into her mouth in one go.

The crowd falls to a hush. This is not customary. Koschei was meant to have his turn with the karavay, but the bride has devoured it. She hasn’t left him a single morsel.

It dawns on the gods first, when Goddess of Death and Rebirth Marena howls from her seat on the groom’s side: “Bozhe moi, Deathless! What have you done?”

Koschei winks.

Ira kneels on the shore of Keuka Lake clawing at her chest and neck. Spittle dots her tremendous chin and she’s violently choking, the bread taking up space inside her that she doesn’t have. Her mind flashes to the Antarctic minke whale, its throat lined with huge expandable grooves, so-called “pleats” that extend all the way from its jaw to its belly button. She tries to think of her own mouth as capable of holding thousands of gallons of water. For once, it does her no good.

The quantity is so overwhelming that, for a long time, Ira doesn’t taste it. When she finally does, she detects some bitter ingredient she hasn’t come across before. Her parents rush to her side, but with a flick of his wrist Koschei sends them barreling backwards into their chairs, stunned immobile.

“Your daughter,” he hisses, “thought she could control me.” He bows his head in the direction of the bridal attendants, his hands a crooked steeple. “In times like these, we must be grateful to our loyal servants, who keep their masters informed of such wicked matters.”

The attendant with white hair in a pert chignon blushes and mumbles, “My pleasure, my pleasure.”

The gods are on the edge of their seats: dinner and a show. The officiant has fainted. The mortals glance at each other uneasily, wondering if this is part of it, whatever “it” is, and generally thinking: my, aren’t these old-fashioned weddings a bit over the top? Ira’s parents gape from the front row.

Ira feels the karavay forcing itself into every cranny, rushing to the back of her throat and going the wrong direction, up into her nasal passage, causing her to sneeze and retch at once. She feels the thin flap of skin between her top incisors tear, feels the bread plunge her new metal teeth into her soft palate. The dull throbbing in her ears makes her realize the karavay must have somehow worked its way in there too, is going to come spilling out of either side of her head any second. Would be nice, she thinks hazily. Sweet release. Even if it has to take her brains with it.

And that’s when it hits her.

“I could have taken care of her sooner, of course,” Koschei continues, “but then we would all have had to miss the party. Besides”—he holds his arms out and spins—“it would be a shame to have so fine a suit and no occasion to wear it.” Chernobog, who has on a velvety tuxedo jacket of stitched-together bats’ wings and considers himself just as sartorially inclined, huffs in staunch agreement.

“Now I’m afraid we must be off. Sorry to leave you nice people with the cleanup. The terms of my visa are simply barbaric, and I have much to attend to before returning home.”

Koschei reaches for the bottle of champagne waiting in a silver ice bucket. Beside it, the collapsed officiant is just now coming to, a bruise already forming where her cheekbone hit the ground. She points over Koschei’s shoulder, eyes all whites.

As Koschei turns, bottle in hand, his beard catches a nail in the ceremonial arch and the smirk, superior and vaguely amused, slips from his face. His skin takes on a peculiar green tinge—not unlike the color of his suit, really— that all the makeup in Hammondsport and greater Steuben County can’t hide.

Because if Ira’s learned anything from planning a wedding, it’s that the details matter. And the rules say to become the head of the household, you need to take the bigger bite. She doesn’t remember anyone specifying that you need to swallow it.

There, beside some four hundred pounds of wet, bite-marked but mostly intact karavay, Ira wipes her mouth with a dainty, ribboned sleeve. She is doubled over in pain but breathing, an absolute affront to matrimonial etiquette—and, come to find out, exceptionally hard to kill. The world is a smear of colors, spinning. The poison has already entered her system. Spitting the bread out won’t save her, but it’ll buy her some time. Besides, there’s a reason they tell you to eat all the rolls in the basket if you plan to be drinking late into the night. All the bread she’s eaten in the past five months has lined her stomach beautifully. It soaks up the toxin Koschei planted.

Koschei sinks to his knees and something thick and invisible oozes out of him, trickling from the sides of his tusks a little at first, then congealing into a small air-bound stream that travels from his horrid mouth, across the length of the arch, and into Ira’s own.

The dazed officiant doesn’t have to say it. It’s one of those would-be-sweet wedding moments: the bride and groom know it, and that’s all that matters. The head of the household on a technicality is the head of the household nonetheless.

Chernobog drops his head into his hands. Dazhbog and Svarozhits slump down in their seats, silently passing a flask of medovukha between them. The mortals are tempted to leave, but most are not rude enough to actually do so: this is a wedding, after all, and there are social protocols, even if the bride herself opts to ignore them. The few who try to get up quickly realize that they, like Ira’s parents, have been paralyzed.

The head of the household gathers her strength and makes her declaration, and Koschei yields reluctantly, having no choice but to do so. “Choice” becomes a foreign word to him, a shadow in the mist of the mind without taste or smell or meaning, as it did to all the women he took and claimed as his own.

Ira speaks their names. For she has been all this time not only a prolific eater, but also a devoted scourer of missing-persons reports, a cataloger of the wedding announcements sections of every major newspaper in the country. She says name after name after name after name. At last, she says the names of the attendants, the scant names she has for them: Freckles and Breathless and even traitorous Chignon. However tightly they sealed her coffin, they too deserve to be free.

Thousands of miles away, in the basement of the mansion, and thousands more, in the dacha’s wine cellar, the women’s chains fall away without warning or explanation, and they unfold their broken bodies and lick the wounds at their wrists and ankles—first their own, then one another’s. They walk to the door, which is inexplicably unlocked, then up the stairwell, whose incline is much slighter than they remember it being all that time ago when they came down. They walk out into the moonlight, holding each other up at the elbows, and when Alice remembers she has left something important down in that dungeon—a twice-folded photograph of her and her best friend, just kids on a rocky beach in matching tankinis—the other women drive her forward and refuse to let her stop. For there is an old superstition about leaving a place. It pertains to any old place; it need not be a prison. To turn around would be a bad omen. One must never go back for forgotten things.

Koschei is infuriated. Ira is doomed. She will not rise like a god. She will not even rise like bread. But dammit if she isn’t taking her precious time to die.

With one foot in Keuka Lake, the centermost of the eleven Finger Lakes, and one foot on the shore, Ira says the final name, shaking from the labor of staying alive. Her red sarafan is wet down the front with slobber and sick, and her towering kokoshnik has been knocked askew, but her parents and the people of Hammondsport will later report that, despite all this, she made the loveliest bride.

Ira looks Koschei square in the eye and raises both hands in the air before her. With her last ounce of life, she lifts the middle finger of one hand. With the other hand, she forms a loose fist, tucks her thumb into the space between her first and second fingers. The sentence, and its translation. So no one will dare misunderstand her.

Then she opens her mouth for the very last time.

Sound travels fast across the warm, still waters of Keuka Lake. That day, the mortals on the other side will remember hearing a joyous, unmistakable whoop.