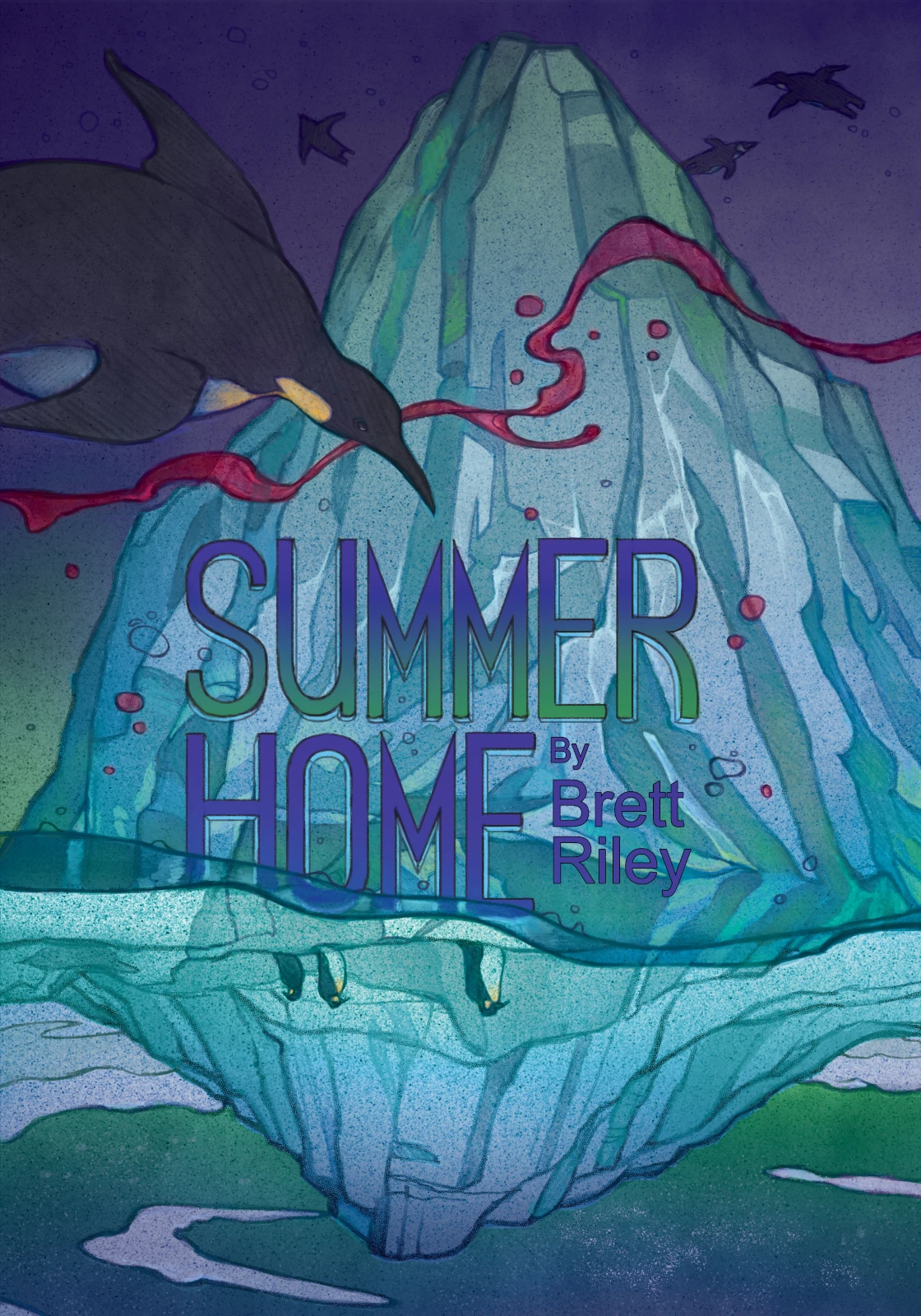

Summer Home

Words By Brett Riley, Art By Michelle Lockamy

Bored and ravenous for something fresh after our long voyage from Seattle, we docked the Caliban and slaughtered the fueling station’s crew. The night smelled rich and fecund as we opened their throats, the shafts of moonlight like God’s fingers thrusting between heavy machines and tanks.

Daria believed in moderation, in lying low and quiet while humans walked their short and often aimless paths from birth to death. Take a Lost One—the homeless man, the runaway—always one at a time and only when our hunger nearly overwhelmed us. Though she was much older than me, she remembered what it felt like to be human, frail, finite. She wept for her food the way some humans lament the deaths of cows and pigs and chickens in miserable, stinking pens.

I never shared her empathy. Every day, I walked the border between submission to Daria’s sensibilities and utter gluttony. At home, just before dawn, I often shook like an addict, moaning from the sheer ache of my voracity. And, though she never admitted it, I think Daria felt it, too. There was a time, a decade or so, when we would gratify our savagery until we were wading in the blood of whole families and flocks of tourists who wandered down the wrong dark alley. In those moments, the light in her eyes grew brighter. She cackled, roared, shredded flesh with tooth and nail. And then, back in our quarters, she would grow sullen and withdrawn; she would stare at walls for hours, watch the blank television screen, consider the ceiling as if some deep void called to her from its featureless white.

We had not fed on that scale in years. It was past time. I leapt from the ship and crushed a man beneath me, drinking deeply as the blood spray misted, each droplet globulous and shimmering against the gray and white snow. I fed as Daria punched through another crewman’s chest, yanked her arm free, and buried her face in the cavity. When she rose, her terrible blood-dripping smile made my heart sing.

Some men tried to fight. Some ran. Some hid. None of it mattered. We had loosed ourselves; we were free.

But nothing lasts. While I drained what I thought was the last crewman, and Daria laughed, maniacal and intoxicated, another man crept up.

He doused her in diesel fuel and immolated her.

No! I cried, as if that word could smother flame.

Her centuries-old flesh smelled like burnt toast. Through the fire ravaging her face, Daria looked at me, her melting eyes like a frightened mouse’s, that magnificent killer smile metamorphosing—a scowl, then a grimace, and finally a wide-open screaming fissure that turned to ash and crumbled at the edges as it grew wider, wider, wider. I roared something unintelligible. Daria turned and ran toward the exit, perhaps hoping the ocean might save her. I pursued, but she fell after fifteen yards, cremated before I could reach her. Falling to my hands and knees, I crawled the last few feet and dug through the ashes, as if I might unearth Daria, alive and whole, ready to ask how I had missed that last man.

Red liquid fell into the remains, a drop, then another, making dime-sized specks of clay. My bloody tears. I had not wept since my awakening. The shock of knowing I still could reverberated through me, and I looked up.

The man stood holding the gas can, shaking, eyes wide and afraid. I stood and walked toward him, ambling, really, as if we were old friends meeting in a park.

Please, mate, he said.

I tore him in half and stomped his remains to paste.

For a long time, I sat in meat and gristle. My rage spent, my grief newborn and sucking in its first breaths, I wept and trembled and tore my hair until my heart felt hollow, a void bigger than space.

Daria’s ashes lay where she fell, stinking of flame and fuel. Not a fragment of bone or cloth remained, no evidence that a sentient being had walked the Earth. Daria. So much more alive than any human had ever been—a survivor, my lover, my life—gone. She had warred with herself for so long, happiest when she took only what she required, as miserable and self-loathing after our occasional feasts as the alcoholic who lets a friend talk her into just one last drink and awakens in a puddle of her own vomit. And now, because I needed the live-wire euphoria of unfettered indulgence, the species she had spent so long protecting from my predations had turned on her like rabid dogs. I might as well have lit the match myself.

I rose to my knees and screamed into the night.

In my solitude, the destruction we had wrought seemed wasteful, demonic, even disrespectful—as if I had spit in Daria’s eye. But I did not understand why. She had walked the humans’ alien world. What possible connection could she have felt to them, to the kind of lives we had lost so long ago? Whence came her wonder, when she had lived so long and seen so much horror? Whence my shame?

Perhaps the answer lay in the destination she had chosen. And so I gathered Daria’s ashes in a cardboard box and set sail.

When I reach the Antarctic shelf, I drop anchor and drink from our stores. The barrels of blood we gathered in Seattle now hold twice what I need. I stay in the galley or the wheelhouse when the sun rides high, reading books we packed, drinking, listening. Compared to the city, this world is quiet, or rather, a different kind of noisy—howling wind, waves lapping against the hull and breaking against the continent, the moaning of the anchor chain when the seas roughen.

One day, a twittering, like songbirds, coupled with dolphin-like chittering. The cacophony grows louder, louder, until it seems to fill the world, and then the first Emperor penguins arrive. They walk in single file as if trained. When they crest the last rise, each one drops to its belly and glides several yards until its momentum dies. Then it stands and waddles within feet of the water, where it belly flops again, plunging headfirst into the sea.

Years ago, I saw a movie about these creatures in a Las Vegas theater. The images touched something in me—the egalitarianism of their gender roles, the way some grief-mad creatures try to steal another bird’s egg. In some ways, the penguins seemed more human than many people I had known. They were certainly more human than I was.

Now, as these females drop into the ocean, fulfilling a biological imperative interspersed with love like a vein of gold in stone, I consider the mating grounds—a place of deep, instinctual connection, like the dens and caves and apartments I shared with Daria. I need to see them.

Clothed in thermals and a heavy parka, I throw a rope over the side, lower myself to the water, and swim until I reach the shelf, dragging myself up onto it with my garments frozen to my skin. But cold means nothing to me, and ice melts. I pull my hood as low as possible to stave off the sun and start walking, passing clumps of females on the way.

I follow the path they wore on the ice until I find the rookery. The Emperors’ songs blast the air like a gale, music fit to drive mortals insane. The males balance eggs on their feet, steadfast against hunger and cold. They guard their young under their feather and fat sacs, bequeathing a warmth I remember only as an abstraction, obeying an instinct beside which self-interest and hunger pale. Daria seemed to remember it. I do not.

What keeps the penguins tethered to this isolation, this lonely waste? How do they understand sacrifice? Love?

I stand apart and wait for revelation.

The rookery is a loose and pulsing ball, black backs and heads juxtaposed against the Antarctic ice, crests so white they seem to disappear into the landscape. Heads and wings and feet waddle and bob. Penguin songs ululate—distinct pitches and rhythms, calls and responses. The smell would overwhelm, if smells bothered me—briny fish, feces and urine, the steel odor of pure cold.

Yes, Daria would have loved it here.

Several males shuffle about the biomass perimeter, searching. Do Emperor penguins make friends? Could these stragglers find solace in each other? Three or four frozen eggs lie on the ice like cobblestones. Perhaps that explains the wandering males, their mournful songs, their melancholic postures.

Over the next few hours, I creep within feet of the outermost ring. Something gnaws inside me, a pulse-like throbbing that is not exactly pain—hunger. I brought no supplies to the rookery. The boat is anchored over seventy miles away.

A full-grown Emperor can weigh nearly a hundred pounds. So much life. I could tear through them like paper. What are the chicks to me, the mates? I could wait and eat them, too, live here for months, forget the human world. Forget Daria.

An eggless male meanders near. I grab it, snap its neck, and sink my teeth deep into its flesh, spitting out feathers to slurp the blood that bubbles from the wound, drinking and drinking and drinking.

The biomass ignores me as I carry the drained carcass out of sight. The body sags in my hands. Its eyes are open, frozen from both temperature and terror.

Is this all I can offer the world? Is this all the world can offer me?

If I forget Daria, I will live as a monster. I will have failed her again.

Night falls, then passes. The first streaks of dawn thrust over the horizon and into the sky like fangs into flesh. I raise my hood and pull the drawstrings tight. Sunlight will not kill me, but it is fire on my skin. I might fend off much of it if I huddle with the biomass.

As I settle on the outer edge, crouching on my heels, I jostle an Emperor that is shifting closer to its brethren. It wobbles. Its egg slips off its feet.

The egg strikes another penguin and rolls in a semicircle. The father makes a strangled sound and gives chase, but the egg rolls underneath me and touches my boot. The bird sees me as if for the first time and stops. I stand up and move away, but the father flees, squawking. Only the males without eggs return his calls.

If the Emperor does not retrieve the egg soon, it will freeze. I move back farther, but the penguin stands at the rookery’s edge, watching me. I retreat again. And again. I lie flat on the ground.

The Emperor approaches his egg. He examines it, head bent like a penitent. He stands that way for a long time. Then he waddles off.

The egg, lying on the ice. As pale as I am. As alone.

I run to it, pick it up, and slip it inside my fur-lined parka. Through my pockets, I take the egg in both hands and rub it, fur against shell. I can move faster than any human. I do not need sleep. Perhaps, if I stay focused, exert just enough pressure and just the right speed, I can create sufficient heat to keep the little inhabitant alive.

Daria and I had lived together since 1906. We met in San Francisco after the great earthquake, when fires raged for three days and stunned humans wandered the city injured, filthy, and weeping. When I first saw her, she was digging through rubble, pulling out the mortally injured. She fed, her predations an act of mercy that I did not understand. I had been made in early August of 1861, when a creature disguised as a wound-dresser found me on the field after First Manassas. When I woke, bestial, my senses enhanced, I slaked my thirst indiscriminately—Union or Confederate, slave or free, child or adult or animal. By 1906, I had recovered enough of my humanity to live in the world, but love, mercy, compassion—these were shapeless figures glimpsed through heavy fog. Yet I could express them, sating my hunger while taking the pain from bodies shattered by bullets, decayed by illnesses or starvation. Daria taught me that, starting in the San Francisco wreckage and on through wars, famines, plagues—acts of a God I no longer knew.

Years ago, on a lark, we settled in Las Vegas, that monument to contradiction—a tourist destination nestled in the burning Mojave, a financial dynamo whose economy even then steamed toward recession. Living on riches built over several lifetimes, we took rooms in Caesars Palace and slept through the long, hot summer days, emerging in the evenings to bathe in the moonlight and lose ourselves in the Strip’s crowds. In the mild winters, we lived and we hunted and we did what others do—gambled, drank, attended concerts and comedy shows and stage productions. Once, we ate a clumsy Cirque du Soleil acrobat. Sometimes we were vicious and cruel, but mostly, we were gracious. When I eyed tourists like aged cuts of meat, Daria whispered promises of love in my ear, found abandoned and miserable loners I could send on to whatever came next.

This year, though, we felt the onset of a vicious torpor. On some days, we could barely muster the energy to leave our rooms. Something about the heat, the relentless sun, had finally worked its will, and we knew that if we did not leave, at least for a while, we might lie in our comfortable bed until we starved.

Let’s go somewhere cold, Daria said. Somewhere less crowded. Just for the summer. We can bring food with us.

Her beauty seemed faded, like our spirits. As if we were aging, fat grapes desiccating on the vine. Alarm in her eyes, alien fear, desperation fit for a youngling.

All right, I said. Where?

Antarctica.

We took a redeye to Seattle, where we selected a one-hundred-and-fifty-six-foot crabbing boat called Caliban. We spent a week procuring fuel and barrels full of blood from every source we could find—drunken sailors, derelicts, drug dealers, and prostitutes. Then we embarked, taking along the Caliban’s frightened captain, who taught us to steer, dock, even fish.

She wanted to trade one desert for another. What could Antarctica offer us—razor sunbeams reflecting off water and ice? A limited, sludgy food supply on a boat that might founder?

But her alarm, her desperation—I loved her; what could I say?

The wind howls, driving ice against my clothing, my exposed skin. The rookery huddles tighter, individuals taking turns on the outer rings.

Then a true storm blows in, windborne ice rolling over the plains like fog. Visibility degenerates. The world turns whitish-gray. Sometimes I can hear the penguins; sometimes I could well be alone, just me and the egg I rub with my coat liner, exerting just enough pressure, a steady rhythm, as if I am polishing a delicate jewel.

The storm blows through the transition to full winter, the two weeks of pure darkness we came for. I had intended to lounge in the captain’s bed with Daria, the heater blowing not because we needed it but for the illusion of normalcy, a maintenance of Daria’s connection to the long human parade we exited long ago. Instead, I stand here, exposed. I cannot see the sky, the horizon, most of the rookery. I walk the perimeter, rubbing my egg in its fur nest, ice slicing my exposed face. Thick black blood drips onto my parka and freezes.

I could go back. Perhaps the cabin’s warmth would suffice. But how would I protect the egg in the water? I ask myself, uncertain as to why it matters.

At the storm’s height, I hunch against the Emperors for warmth. I rub and rub and rub the shell. Several penguins nudge me as they waddle until, off-balance, I fall onto my back. I sit up, but before I can regain my crouch, birds have huddled against me, trapping my legs. Their backs’ warmth bleeds into my parka, my egg. So I sit.

Perhaps a day later, the storm blows out. The Emperors mutter and shift, the outer ring absorbed and replaced with new penguins that put their backs to the cold, to me. Overhead, millions of stars glitter, as does the moonlight on the ice, which stretches farther than I can see.

I try to stand, but the storm has frozen me to the ground.

I take out the egg and put it in my parka’s pocket. Then I brace my hands against the ground and push. The ice cracks, splinters, and I rip free, regain my feet, and transfer the egg back inside my coat. On the ground, fragments of trousers and bits of bloody flesh. The backs of my legs sizzle. This continent is tearing me apart.

The physical wounds will heal when I feed, yet I see no lone Emperors. I could kill any of the fathers near me, but the eggs would freeze. And when the daylight returns, more flesh will be exposed to the sun.

I have more clothes on the boat. I could go back.

But the egg.

I prepare myself for more pain.

If Daria were here, I could pass the egg to her, like the penguins do, and return to the ship. Of course, if she were here, I would still be on the boat, lying on deck with her and bathing in the starlight, drinking our fill, holding each other.

You are all I have left, I say to the egg. We are lost together, you and me.

The rookery rotates, shifts, huddles. I stand behind them, close enough for them to feel my breath, if I breathed. Above us, the stars wink and shimmer. Their light is its own ghost, the echo of ancient dying.

Another storm strikes, obscuring the heavens. Just before the ice haboob overruns us, I spot an eggless Emperor and feed, his life’s blood enough to heal my shredded legs. Perhaps I’ve widowed some female fattening herself in the ocean even now. Still, penguin couplings rarely last more than one season. The loss of the egg will affect the female more than her mate’s death. Or so I tell myself.

I crouch, my renewed strength giving me greater balance.

Soon, something wondrous happens.

The penguins shift, nudging me like gentle surf. Some of them waddle beside me, behind me. They press me forward, inward, absorbing me into their midst. I shuffle forward, rubbing the egg, rubbing, rubbing. They feel like shelter. In time, I find the center of the biomass, my hooded head looming over the penguins’, their muted conversations like chatter at a cocktail party.

Is this what it is like for the chick, nestled inside something that is part of itself, yet distinct? Is this what humans feel inside their mothers’ wombs? How the Earth feels in its atmosphere, blanketed with gases that keep the cold of space at bay?

I sit at the rookery’s core, a predator nestled in pure life, the blood and fat and bone of it all.

How foreign. How miraculous.

The two-week night ends. I have rubbed the egg constantly, grateful that I no longer produce lactic acid or require adenosine triphosphate. However, since my acceptance into the rookery, some vestige of my lost humanity has prevented me from eating even eggless Emperors, and the lack of sustenance means that my exposed skin does not heal. In days, the penguins’ chattering becomes a dim roar, like a crowd might sound from outside a stadium. Pain fogs my thoughts. Even darkness seems too bright. I keep my eyes closed most of the time, letting the birds direct me as I rub the egg. How do they feel, these odd creatures that stand nearly motionless for two months, starving? Do they hallucinate? Or regret?

A handful of desperate birds have abandoned their offspring and shuffled back toward the sea, falling onto their bellies and sledding, waddling, sledding, waddling out of sight. I would rescue those eggs, too, but I cannot hold them and warm them all at the same time. My body is as cold as the continent. Fire is impossible. What would I start it with? How would I feed it?

I dream of dropping the egg and eating every Emperor on this blasted strand of nowhere—grabbing them one at a time and ripping them open, drinking, feeling their lifeforce barrel through me like a train. Some would understand and flee, and I would hunt down as many as I could, drinking until I was ready to burst like a gray tick on a dog’s back. Then I would stalk the rest just for sport. I could wipe them out, grind their bones under my boots until no trace of them remained.

To a starving creature like me, that idea feels like a drug.

Later, I dream of dying on the ice—falling at the rookery’s edge, crushing the egg, freezing to the spot or, like some humans, ripping off my clothes. The cold would matter little, but the sun would bake me alive, turning my world into a red haze of pain until I starved to death and turned to ash as surely as if I had burned, my history blowing away in the wind and mixing with the ocean’s salt.

On and on, we stand and shift.

And then the eggs begin to hatch. A few at first, then a wave of peckings, breakings, small and fuzzy creatures peeking at the cold, harsh world from underneath their fathers’ fat sacs. One day, a tapping inside my egg. I take it out of my parka and hold it up to the light, ignoring my pain.

A beak breaks the shell. A head forces its way out. Small, dark, curious eyes watch me.

I drop the shell fragments on the ice and tuck the chick inside my parka, nestled in the fur again. Its heartbeat thumps against my chest.

The females return, fattened and fresh and ready to meet their children. I sit on the ice with the chick in my hands. I cannot call its mother to us. I never heard her mate’s song. The females greet their consorts. The males transfer the chicks to the feet of the mothers, who regurgitate fish into the younglings’ open mouths. The males say whatever passes for goodbye in the Emperors’ world and set off for the sea, where they can eat and rejuvenate. A handful of females wander about, calling for mates who do not answer, looking for offspring that were never hatched. Their grief is a living thing, pulsing in their plaintive cries, in their desperate dashes about the rookery.

My chick watches all this from my parka, only its head visible.

When the females push their chicks onto the ice so that they may learn to live in this world, I hold mine at eye level, looking into its face. It still seems more like a ball of fluff than a bird. I stroke its head, its little beak. I know little about penguin anatomy, but I prefer to believe it is female, a new life in the world to replace the one I lost.

Your name is Daria, I say.

Then I set her on the ice.

She waddles about for a moment and then returns, nestling against my leg. Like the mothers, I move away, forcing her to stand, walk, contend with the cold. She looks at me as if I am God. I wish I were. I want to pick her up and carry her back to the boat and feed her from the frozen stores of bait cod the crabbers packed before we took their ship. I want to sail back to America and find a place in Minnesota, North Dakota, some cold state where little Daria might live at least part of the year in conditions resembling the life for which she was born. But I know better than most what kind of existence that would be—always the stranger, at war with the world even in the most peaceful moments.

Besides, a creature like me has nothing in common with God, or any other parent.

I nudge little Daria away with my hands. She chirps. I stand up and back away. She tilts her head.

Around us, mothers and chicks eat, walk, sing. The only child I have ever had stares at me for a long time. Every time she moves toward me, I step away.

Soon, a lone female approaches. She inspects little Daria, who looks at the newcomer with something like wonder. The female moves closer and closer. Before I know it, she is feeding my little penguin, throat working, the chick’s mouth open. They get acquainted, the female bending her neck low enough to stroke Daria with her beak, talking in her strange language.

I would give my life to know what they are saying. But here, too, I stand alone.

I sneak away, walking backward until I am sure the chick is not following. Every step feels like a mile. It is harder than I would have ever imagined. As if a part of me has died again. An amputation. Then I turn and run.

Fifty yards away, I look back. They are gone.

Miles later, I stumble to the ice’s edge. The Caliban floats where I left it. A handful of males who have walked with me slide into the water on their bellies. I am weak, the backs of my legs sizzling in the sunlight, so I take off my parka and slide in too, slipping down the cutting ice and into the frigid waters. Emperors swim away like torpedoes, searching for food. My stores sit on the Caliban’s deck, frozen solid. When I reach the boat, I can eat, rest, scatter Daria’s ashes, and decide what is next.

For a while, I swim on the surface, but the sun reflecting on the water poisons me, so I dive deep, swimming along the bottom toward the ship’s shadow. Ignoring my hunger, my outraged skin, my broken heart, I watch the penguins—in the filtered light of this icy, silent world—swimming in the wake of vanished generations. They zoom over my head, snapping up fish, as graceful as their feathered brethren in the sky. They barrel roll and loop and twirl, every minute of their brief lives filled with purpose and singular beauty.

That first day in San Francisco, Daria held a dust-covered human baby, cooing and humming, until she quieted. Our paths are limited, Daria said, but every possibility winds before her, if we can stand aside.

That was the thing Daria was always able to see that I couldn’t—the magnificence of living beings thriving in a wasteland, their dim knowledge of their own mortality driving them toward connections both profound and temporary. Their descendants will shine on long after I follow her into the last darkness. They will be hunting, walking, mating, departing, and returning, trudging over my tracks until it seems that I had never come at all.