Strange Pathways: A Pioneering Writer Feature with Benjamin Percy

Words By Benjamin Percy, Art By Ejiwa Ebenebe

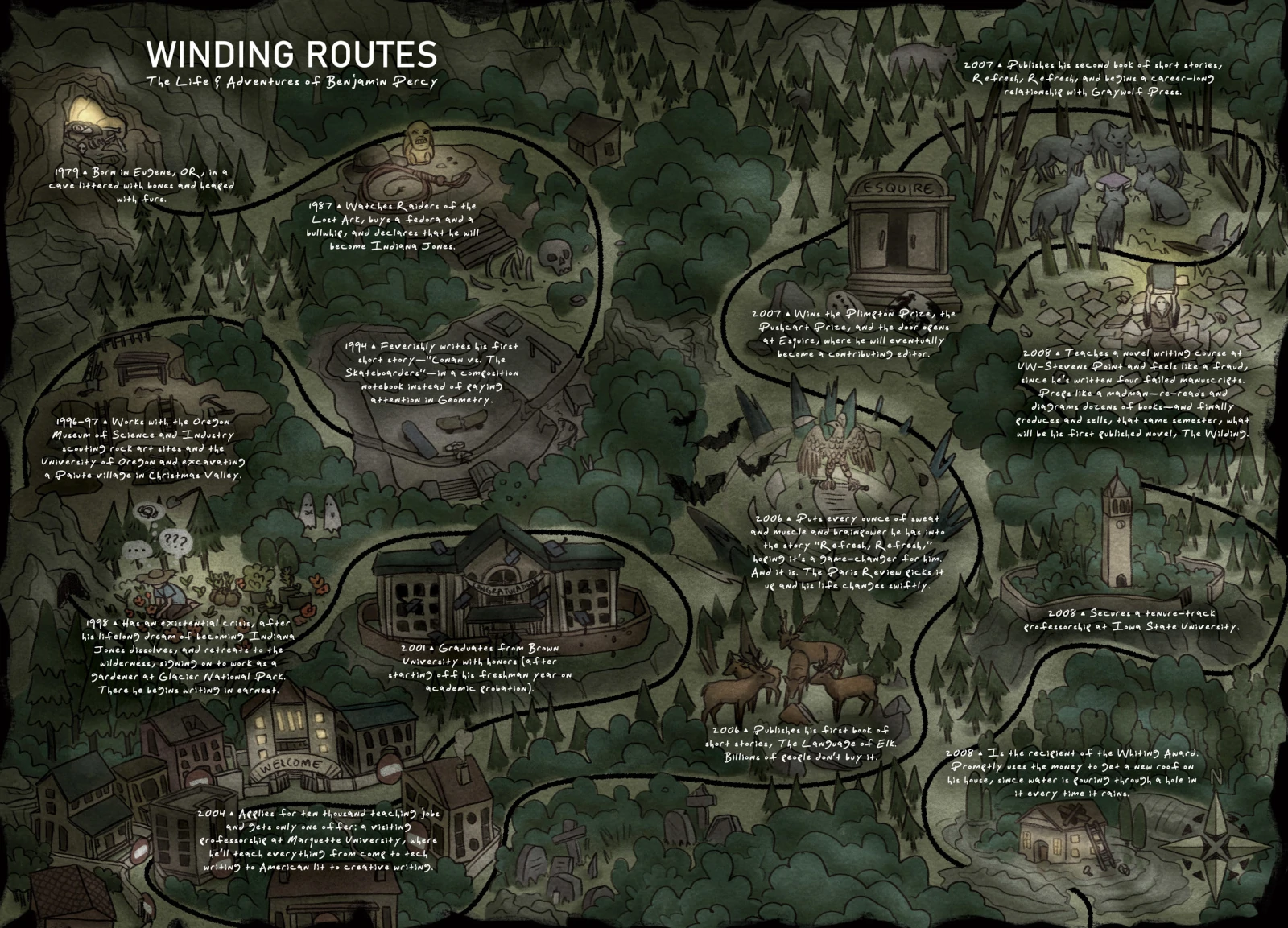

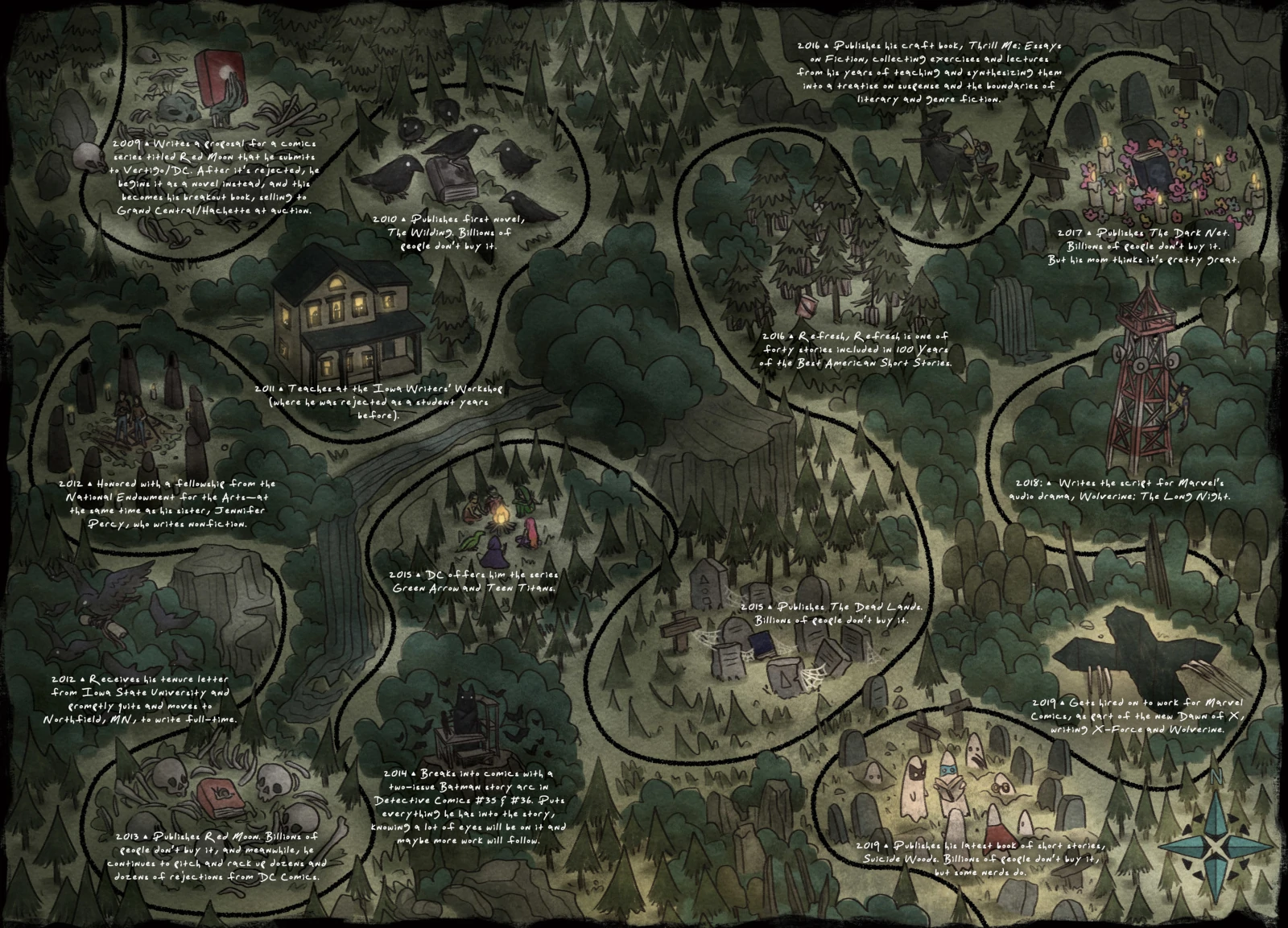

During his celebrated career, Benjamin Percy has blurred the line between literary and genre, becoming a champion for beautifully written, speculative work.

He is the author of five novels (most recently The Ninth Metal, which will release in 2021 with Houghton Mifflin Harcourt), three story collections, and a book of essays. He writes Wolverine and X-Force for Marvel, and his past work in comics includes Detective Comics, Green Arrow, Nightwing, Teen Titans, and James Bond. His fiction and nonfiction have been published in Esquire, GQ, Time, The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, and The Paris Review. His honors include the Whiting Award, the Plimpton Prize, two Pushcart Prizes, an NEA fellowship, the iHeart Radio Award for Best Scripted Podcast, and inclusion in Best American Short Stories and Best American Comics.

In our interview, Percy talks about comics, failed manuscripts, generating material, and monsters, new and old. Be sure to stick around after the interview for the first look at his newest short story, “The Night Road.”

An Interview with Benjamin Percy

By Dani Hedlund

Almost everything you write is saturated in this feeling of the strange—from a boy made out of ice, to wrestling dummies come to life, to post-apocalyptic Lewis and Clark with magic. Where do you find inspiration for the strangeness and the speculative elements of your work?

That’s the way I’m hardwired; to see reality through a cracked mirror. I’m rolling down the freeway and I might glance at a water tower and imagine its long metal legs uprooting and the thing becoming kind of a metal spider chasing me along the roadside. I might wake up in the middle of the night and be certain I heard a thump in the attic. My wheels begin to spin as I imagine some sort of demon scratching a pentagram into the woodwork above me. Or I might be at the grocery store and look at a pile of oranges and one of them looks a bit like an eye looking back at me as I reach for it. I think that’s because I grew up on a steady diet of Stephen King, superheroes, Shirley Jackson, Octavia Butler, and Ursula K. Le Guin. I think it’s because I grew up in isolated areas where I wanted to be long ago and far away. I oftentimes shoved reality aside and escaped into the ether. All of those things came together to make the speculative my doorway of choice when it comes to putting prose on the page.

You’re not only known for writing through a speculative lens, but also for using it to tackle real-world issues. Do you approach a project knowing what kind of real-world issue you want to tackle? Does it come together organically? When do those elements coincide?

I always look for the about-ness of the piece and I mean capital “A” About-ness. Not just what is happening in the story, but what it means. What is the subtext of the situation? I need some sort of focusing agent, which might be a post-apocalyptic narrative or a story about werewolves living among us. I’m trying to figure out what’s beneath the surface. If you look at literary fiction, you see the same undercurrents. Let’s say the story is about Gatsby and his desire for Daisy, but there’s subtext beneath that. He doesn’t actually want Daisy, what he wants is to be accepted by the old money families of the east coast and he’ll never accomplish that. So here I am, writing a story about werewolves living amongst us and the fear of infection. That story, “Red Moon,” is actually about xenophobia, and has a lot more in common with the X-Men than it does Twilight. Usually, what I’m thinking about is—when I’m dreaming up my big projects especially—what do we fear right now? What makes us uncomfortable? If you look back to Frankenstein, it was born out of the industrial revolution, born out of the fear of science and technology. If you look at Invasion of the Body Snatchers, it’s about the red scare, McCarthyism, an invisible enemy living just down the block. If you look at Godzilla, post-atomic anxieties. If you look at the Living Dead movies, George Romero reinvents the metaphor in every era in which those films were produced. If you look at what’s happening right now, in this country, things are very culturally, politically divisive. Jordan Peele is someone who has done a brilliant job tapping into that in his horror features Get Out and Us. There’s a similar generative process to my own work where I’m oftentimes trying to take my knife to the nerve of the moment. The monster reveals itself.

You have dabbled in so many mediums: short fiction, novel-length, fiction comics, a craft book, and screenplays. How do you balance all these different mediums? When you have a new idea, how do you figure out the best medium?

If it’s a novel, I’m thinking about it for years before I actually start to hammer the keyboard. When I first started off, I wrote four failed novels and as a result of that, I am scared to death of something turning to dust in my hands. I think most writers will tell you the same, that they’ve got projects in a drawer somewhere and you have to write those failed manuscripts to get to the good stuff. Now, I will create maps, story charts, brainstorm clusters and I have this closet tacked full of ideas, blueprints, conversations overheard in bars and articles torn from newspapers. I use this dark room as my nightmare factory. I have screenplays and novel concepts up on the wall that I’ve been thinking about for five years for some of them. I don’t know everything when I begin one of these projects but I know quite a lot. I like to refer to my outlines as a kind of constellation and I know the brightest stars. I want to improvise my way between those stars to some degree. If you look at a constellation in the sky, you can kind of imagine the gossamer threads that unite them and that’s how I approach high concept novels or screenplays.

With comics, when it comes to working for Marvel and DC, you are not allowed to stumble your way through the dark and figure things out as you go along because a lot of people are relying on you. What I have to do is propose a bible first and that says what I’m going to do with this character, and some of the stories I’m going to explore, and what’s the legacy of this hero, and how can we bring them forward into the future in an original way. For every single story arc, after the pitch is accepted, I have to do basically the same thing. I have to pitch and say that these six issues are going to be about this, and these next three issues will be about that. That goes through the Marvel wringer and I get feedback, but even then on an issue-by-issue basis I have to write out a beat sheet before it’s accepted and move it into script. It sort of changes project to project as to how much forethought is put into it, how flexible or inflexible the venue might be. If I’m writing short stories, I’m essentially writing them for myself; it’s more of a case of just a glimmer. I have an image that I’m chasing or I have a voice that I’m chasing. If I’m writing screenplays or comic concepts, I’m definitely keeping the strict regulations of that venue in mind. If I’m writing novels, I have to consider the fact that this will take years to compose and all of these things are influencing the way I hammer together a project.

You have written in so many genres. How do you see all these different genres iIf for some reason a god came down and said, “Ben you can only write one form of story,” and you had to choose, which would it be?

I would certainly not write screenplays, because the amount of maddening oversight that comes from Hollywood would drive me insane. I think comics suit my sensibility best in that they’re a sprint and I’m kind of an idea factory. I’m putting all of my sweat and muscle into these issues but I can rattle them all out faster than I can a novel, which takes so much care and time. Writing novels, as enjoyable as that is, is a lonely pursuit. Writing comics means you’re part of a team. You and the artist are strenuously trying to tell the best story possible. How can we arrange this action set piece to be truly operatic and how can we build a new villain that readers will go crazy for? It’s infectious, that sort of collective enthusiasm. I think I’ve found my favorite home in comics.

You mentioned you had four failed manuscripts that have broken your heart slowly. Can you tell us about the one that broke your heart the most?

Probably the last, because it felt like there was a lot more at stake at that moment. I’d just had a kid and my job was uncertain. I was a visiting professor at the time, my tenure was running out and I was on the job market. Everything was at stake selling this novel. I remember I had come home from teaching, and it had been a long week and I was talking to my agent about how she had sent it off all over town. Everybody said that I had promise and they wanted to read more of my work, but this manuscript just wasn’t doing it for them. I ended up lying on a couch and drinking a lot of whiskey in the dark, listening to blues. I got up the next day and I got back to work. Rejection wears away your heart, and no matter what artistic discipline you pursue, writer, painter, or a musician, you’re going to hear no over and over again. Maybe you send off a story and get thirty-nine rejections, but the fortieth is a yes. How many people have the resolve to wait for that fortieth slip to arrive in the mail? Most people give up after three, after seven, after eleven. How many people have the resolve to write that fifth novel after all those hundreds of pages, thousands of hours went up in flames?

Aside from extraordinary stubbornness, what do you think you learned as a writer from those failed manuscripts?

If you write a short story and it fails to launch, usually you can put a finger on what you did wrong. With a novel, there are a hundred and fifty things wrong with it, usually, and it’s a lot harder to bully your way toward the next draft or the next project and know what to do. When I was in grad school, I felt like I was struggling with structure. So I took an author that I felt had airtight stories, like Flannery O’Connor, and I would read and re-read one of her stories. Read it seven times, the eighth time I would have a legal tablet out and scratch out the beats of it like; paragraph one, character A introduced via dialogue as jealous and spiteful; paragraph two, theme introduced via description of a decrepit neighborhood that is filtered through the mother’s point of view. I’d go through beat-by-beat like that and then I would take that skeleton and I would write another story based upon it that bore no resemblance to the original.

One of the things that helped facilitate this process was that I had to teach a novel-writing course. Nothing puts the fraud police on your back more than teaching a course on novels when you haven’t published one yourself. I thought, I’m going to be standing up in front of thirty students in the fall and trying to teach them how to write a novel and I haven’t published one myself. I got all these books and they all had different approaches. I taught that course with all different models. As I was forcing the students to think about the different structures, I was thinking about the structure of my own work. I don’t think it’s any coincidence I sold my first novel, The Wilding, that same semester.

When do you decide that a manuscript or big idea should be let go? Or you think, “Okay, my agent doesn’t love this, can I just gut it?” Where is that decision?

Sometimes we submitted something to every publisher, they said no, and then I was like, “Alright,” and moved on to the next thing. But I kept that scene with the owl, for instance. I’ve never had trouble moving on from a project because I know there’s more timber coming down the trail. Just about everybody I know has four or five dead manuscripts in the drawer and it’s a part of the game. It’s a part putting in those ten thousand hours that help you approach a kind of mystery. Another essential lesson that I’ve learned is the pivot. I wrote a screenplay with a Die Hard premise that takes place in an airport under quarantine, and it was rejected all over Hollywood. In the meantime, I submit it to DC comics and it is rejected. Finally, Mark Doyle, whom I’ve developed a relationship with, takes on the Bat-family and says, “Okay Percy, you’re never going to leave me alone, so I have an opening for a two-issue detective comic. What do you have?” What I had was a screenplay that I believed in. So I essentially took Bruce Willis out of the scenario and put Bruce Wayne in and that became my comics debut. The Batman story that launched my whole comics career was only published after many years of rejection. And now I’m writing Wolverine. It circles back to what I was saying before about stubbornness and resolve. When hearing no, or even when giving up on one thing, you’re not giving up overall.

You have been a trailblazer in showing that speculative and genre fiction can be written as beautifully as literary fiction and have the same deeply human themes. What was it like to take part in this time where people didn’t think that was possible?

I can take some credit but not full credit of course, because Margaret Atwood’s been doing this for years. I walked into my first creative writing workshop ready to write stories about vampires, robots with lasers for eyes, and barbarians with wooly underpants, and was immediately told that would not happen. Genre was forbidden and for the next four, five years, I read and wrote literary fiction almost exclusively. I fell in love with so many writers I had never heard of before. Then I read an essay by Michael Chabon in the introduction to this book called Thrilling Tales where he said that he was a bored reader and a bored writer. He talked about these imaginary boundaries between literary and genre fiction and how this anthology would be filled with the kinds of stories you would have loved growing up. The collection is hit or miss, but you can tell that all the writers are having a lot of fun.

When I read that I asked myself, what if I had been invited to write a story for this anthology? It just changed my thinking completely because I realized the track I was on was not what brought me to creative writing to begin with. So the stories I became most interested in thereafter were the ones that occupied a kind of ghostland, that were neither fish nor fowl; both literary and genre. I wanted to tell stories that had pretty sentences and subterranean themes and glowing metaphors, yes. But also exploding helicopters. Time has changed, the tide is shifted. You have Marlon James publishing books like Black Leopard, Red Wolf. You have the Karen Russells and Manuel Gonzaleses of the world writing shorts stories that defy categorization. It’s a good time to be splashing around in the pool.

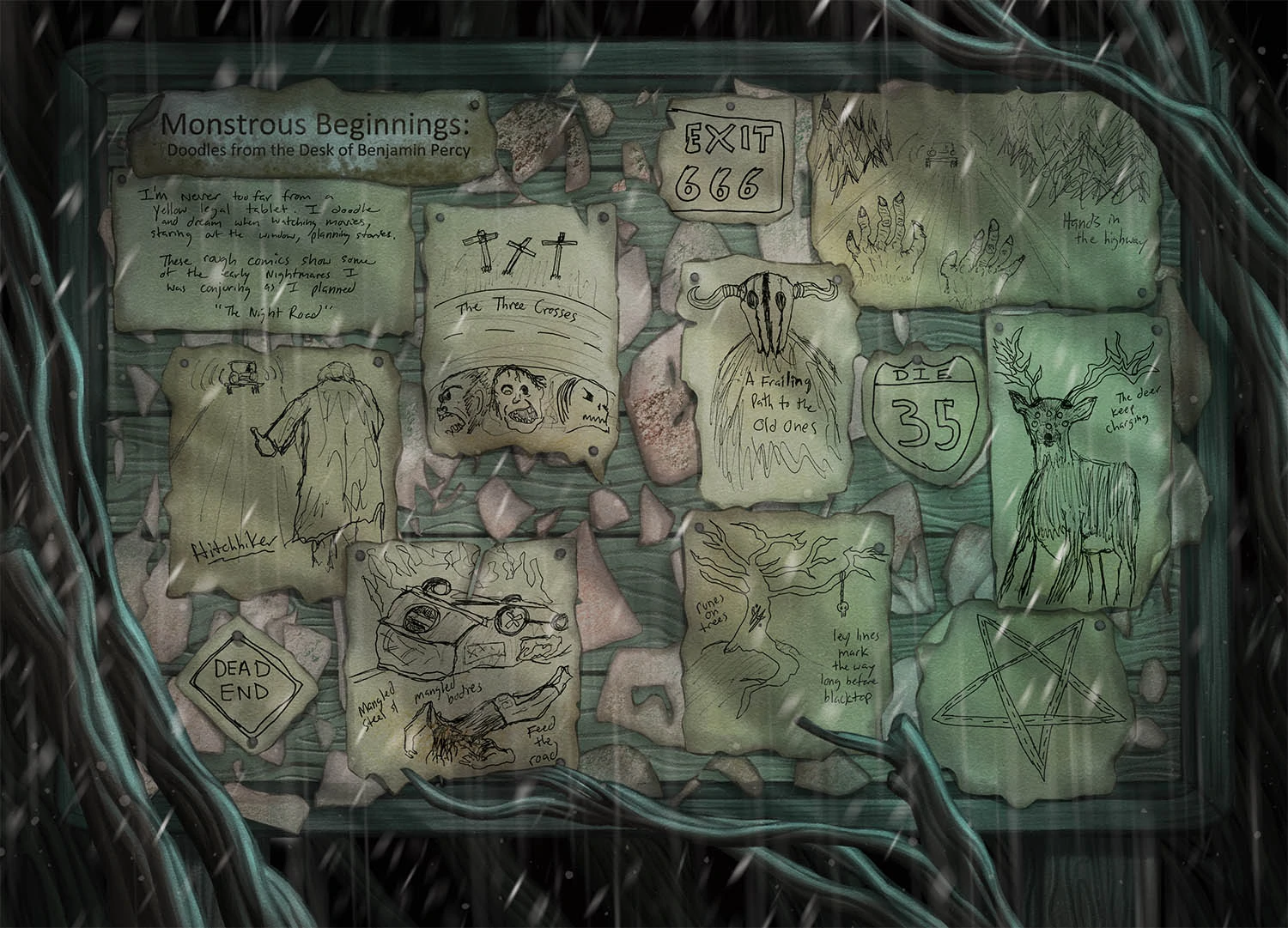

What follows this interview is an original short story that you’ve written called “The Night Road.” Can you tell us a little bit about where the idea came from and, to echo your own phrase back to you, what is the capital “A” about-ness for this story?

I’ve been reading a lot of Shirley Jackson lately and with The Haunting of Hill House she takes on a popular horror trope of the terrible place. I think she does something very interesting in that she filters the terrible place through an unreliable point of view. You never know when you’re reading The Haunting of Hill House whether the terrible things that are transpiring are the result of Eleanor or the place itself. I’ve been interested in playing around with that and in this story, I made a monster out of the road that everybody knows, which seems to haunt every community. You see it in a blur when you pass by. It’s the place where there are crosses that are hammered into ditches draped in a moldering bouquet of flowers. Or that road where people always seem to be breaking down, getting flat tires, where a friend or a family member spins out or hits a deer.

The idea is to make this story at once grounded in a certain terrible place and then recognize that place is everyplace. To create a kind of mosaic pattern with this, a fractured sparkitecture that will hopefully affect your psyche and make you feel scattered and uncertain yourself, directionally. Because, as the people traverse this road, they get lost, and I wanted to create a kind of torn up map for the reader, for them to arrive at a state like a compass-spinning confusion. So that they’re lost in a dark wood or they’re lost in a fallow cornfield. The eyes of owls and the eyes of deer are glowing in the ditches. Mist is rising from a bog, snow is hissing along the road, these different sorts of haunting effects are all swirling together in a dark fantasia that hopefully makes you feel infected and paranoid.

There is a road, a country road, in Minnesota—or maybe it’s in Idaho or Florida or Ohio—that the locals never drive at night. Because they know what can happen there.

It is called County HL. Or Black River Road. Or is it Highway Zero? No one can remember for sure. The details get slippery when people talk about it. Maybe because fear sears the mind like burnt rubber on blacktop. Or maybe because memory, like the night road, follows no map. The way is easily lost.

One time, on a dare, a teenage boy named Jimmy Rictor drove his two friends along the night road. They had been drinking watery beer at the gravel pit and their hearts fizzed with stupid courage and the bass pounding from the car speakers. The Pontiac groaned up to speed as the road snaked through cornfields and ponds and woods. Leaves rattled in their wake. A dead raccoon grinned from the ditch. Then, when the road cut across a bog with mist threading from it, Jimmy snapped off the radio and lifted his foot from the gas and rolled to a stop. His friends asked him what he was doing, and he said he heard some kids died here. Their car slipped off the road and into the bog, where their throats and lungs choked with mud. He tapped at the window with his finger and they noticed then the three small paint-flecked crosses hammered into the gravel shoulder with some flower bouquets moldering beneath them. “Rumor has it,” Jimmy said, “if you flash your brights three times, you’ll see their ghosts.” Would the mist take bodily form? Would their bodies hang in the air before the car with water dripping from them? Would the bog bubble and splash as their corpses clambered out of the murk? Would they appear suddenly in the backseat with beetles scuttling out of their mouths, their gray skin sloughing off their bones? Jimmy wasn’t sure, but he said, “How about let’s find out?” He raised his hand to the signal lever and clicked his high beams once. His friends laughed the first time, but the laughter was cracked and high pitched. The second time the headlights flashed, there was a long beat of silence, before one of them said, “Okay. Let’s just go. Can we just go?” It was then that the brights blazed for the third and final time, and the kids who died here were them.

There are instances of people driving along the night road and speaking in a language they do not comprehend. They hiss and howl and jabber and grunt and grind their teeth until they splinter. And over time they come to realize that they are reading. The glyphs and ciphers—shaped like claws and mouths and genitals—scratched into trees and onto the rocks that border the road. This is the voice of the elemental, the oldest tongue.

Sometimes, in the winter, snow whitens and polishes the night road, blown by the wind, swirling in hypnotic patterns. If you look close, you’re sure to see hands beckoning and faces smiling, and if you listen close, you’ll hear voices whispering in the sudden static of the radio. Don’t look, and don’t listen. Because if you do, your foot will ease off the gas and feather the brake. You will strangle the gearshift and shift into park and step out of your car and the hands will rise from below and coldly grip your ankles and the asphalt will go soft and mucky and lip at you as you are pulled down, down, down. The next morning your car will be discovered with the door open and the fuel tank empty and the battery dead, and people will say that you must have wandered off for help and died of hypothermia and maybe your body will be discovered in the spring? But they are wrong. You will not be found—you will be forgotten. Until it is your face they see in the snow, your hands beckoning.

Even by day, there is a gloom to Black River Road. A dimming. A thickening of shadows. People assume a cloud filters the sunlight. Or a hardwood forest throws shade. But it is always this way, no matter if the sky is clear or if the road roams through the open air of a cornfield. The air might be eclipsed, as if in a permanent gloaming, but there is some brightness to be found. In the eyes of owls glowing a lamp-lit yellow as they swoop across the road. Or in the broken glass that sparkles like starlight at noon. The ditches are fiery with splashes of sumac in the fall and the pavement is smeared with rough candy-red stripes of blood year-round.

Jimmy Rictor’s father went looking for him. By day he would drive County HL, scanning the ditches, pulling over now and then to study the blacktop. Over time he came to realize that the way changed, that the path was always different. Sometimes the road ran straight and sometimes it wound and sometimes it rippled up and down hills and spanned a black-watered river, but never in the same place or pattern. Sometimes, at the bend in the road, there would be a dead oak tree with ravens leafing its branches and sometimes there would be an unwired telephone pole with a cat nailed to it. So he tried to map it. He kept a legal tablet balanced on his knees and he sketched out the route while driving five miles per hour and tracking the odometer. The first time he drove the road, it made the shape of a snake, and the second time he drove the road, it made the shape of a pentangle. He always made sure he was off the road before the sunset, but on this occasion the road never ended, turning and folding back on itself, knotting around him, claiming him as it did his son.

One rainy night Susan Haight was driving her family home and decided to take a shortcut. Her husband said it was a bad idea, and she said, “What’s the worst that can happen?” as she turned on to the night road. The trees seemed to lean closer and her headlights to dim. It wasn’t long before a figure appeared in the anemic wash of her headlights. He had his thumb out. He wore a poncho that hooded his face and he stood hunched, turtled beneath the bulk of his backpack. “Oh, poor man,” Susan said. “He’s soaked to the bone.” Her husband said he wouldn’t stop, she shouldn’t stop, but Susan reminded him of the time they hiked across California in their twenties and how appreciative they were for rides, food, the kindness of strangers. “But what about the kids?” her husband said, and Susan said, “They’ll be fine. They’re asleep in the wayback. We’ll drive him to the nearest gas station and drop him off.” Her husband said he thought it was a bad idea, just like this detour, and she said, “You think everything is a bad idea.” She parked along the shoulder and the rear door smacked open and the hitchhiker tossed in his backpack and climbed inside. He did not say thank you. He did not answer Susan’s question of “Pretty ugly out there, right?” and “Where you headed?” He did not even pull back the hood of his poncho, so only his gray beard was visible, spilling down his chest like a thick damp clump of moss. Susan pulled onto the road again and fiddled with the climate control because the windows had suddenly fogged over. There was a smell she couldn’t quite place. She was reminded of the time she discovered a spoiled sack of potatoes in the basement. Or the time when she returned home from vacation to find their parakeet dead at the bottom of its cage with maggots squirming through its yellow feathers. The windshield remained fogged, so she fiddled with the vents and controls, and when she looked up again she found that she was alone in the station wagon. Her husband was gone. Her children were gone. The hitchhiker was gone. But the backpack was still there. She called out their names. She reached behind her and grabbed at the heavy backpack and her hand came away tacky with blood. Or maybe it was already bloody before.

Her eyes settled on the windshield and across the words scrawled through the fog of it: “YOU DID THIS.”

Have you ever heard the story of the cemetery off Highway Zero? It’s just past the covered bridge. Or just before it. Or nowhere near it at all. It overlooks a bluff, or it is at the bottom of a bluff. The ground is rocky here, and the graves so shallow that the grass is bellied where it hides bodies. There is a gravestone there—veined with lichen—on which your name has not yet been carved.

In the spring, when the snowdrifts melt, carcasses emerge. Deer missing their legs. Possums showing teeth that look like the spikes of hoarfrost. A crow sleeved with ice so that it looks like a shard of obsidian. This is why you should never eat the wild asparagus that grows thickly in the ditches. The vegetable might give off a delicious, earthy funk as you steam it. But even if you soak it with a generous pat of butter, even if you jewel it with salt and dirty it with pepper, it will taste curious, wrong, off. You won’t be able to describe the flavor except as wrong because you don’t know what necrotic flesh tastes like.

Some believe that County HL is haunted because a member of the construction crew, the paver, came home from work and discovered his wife in bed with another man. He killed them both and boiled them in hot tar and steamrolled their bodies into the road. When you drive there at night, the specks of white glinting in the blacktop are teeth, and it is as if the road has opened its mouth to swallow you.

The deer watch from the ditches, their eyes glowing and their antlers branching into the dark like ossified veins. When a car approaches, they leap all at once into the road, throwing themselves in its way. Their horns screech and gash the metal. Their bodies come apart and muck the wheel wells and tangle up the undercarriage. The grill punches their legs and sends their bodies soaring into the windshield that spiders lines upon impact. And then, even after the car screeches to a rocking stop, there are more of them, hoofing and bounding from the woods, knotting around your ruined vehicle, waiting for you to kick open the door and make a run for it or cook to death within the smoking cab.

The road existed long before asphalt, before gravel, before automobiles, before wagons, before people. Wolves would hunt along it. Spiders and centipedes would cluster along it. Crows would fly above in a dark churning stream. Some people talk of ley lines, channels of energy that lace the earth. Cathedrals and temples and stone monoliths are arranged upon them. Some are dark and some are light. Planes and cars and boats and hikers disappear near them. You cannot destroy the road, because what you understand to be the road itself—with its tar and paint and scarred guardrails—is nothing but clothing. But Susan Haight did not know this. She wanted to punish the road for taking her family. She splashed cans of gasoline across it and lit a match and orange and blue flames rose with the sound of torn fabric. She pleasured in the way the tar bubbled and deformed. Then she hoisted a pickaxe and swung it with her whole body and its tooth bit the blacktop once, twice, three times, four. She swung until her shoulders and wrists felt torn, until the handle of the pickaxe splintered and snapped, until she fell to her knees, and then laid her body down across the yellow line, waiting for someone to come along and end her and the pain she felt. Because she could not kill the road any more than she could kill a mountain or a river. The way would remain. The stain of it.

You made a wrong turn somewhere. Your phone offers no signal. You’re not sure how you ended up here and you’re not sure how you’ll ever find your way back. It wasn’t there a moment ago, but a long black car has appeared behind you. Or maybe it is a snowplow with a rusted blade. Its headlights are off, though this moonless night is darker than a cave. Your eyes jog between the rearview mirror and the road before you. A bulky shadow is visible behind the wheel. A horn sounds for what must be a minute, a ragged blare, like an alarm signaling the end of time. When you speed up, it speeds up. When you slow down, it rides your bumper, nudging it with a screeching lurch. You almost miss a sharp curve. You almost hit a deer as it bounds out of the woods. You can feel the hum of the engine in your hands as you white-knuckle the wheel. The yellow-striped blacktop unscrolls beneath you. The night road is yours to navigate. Where will you go next? What story will you become?