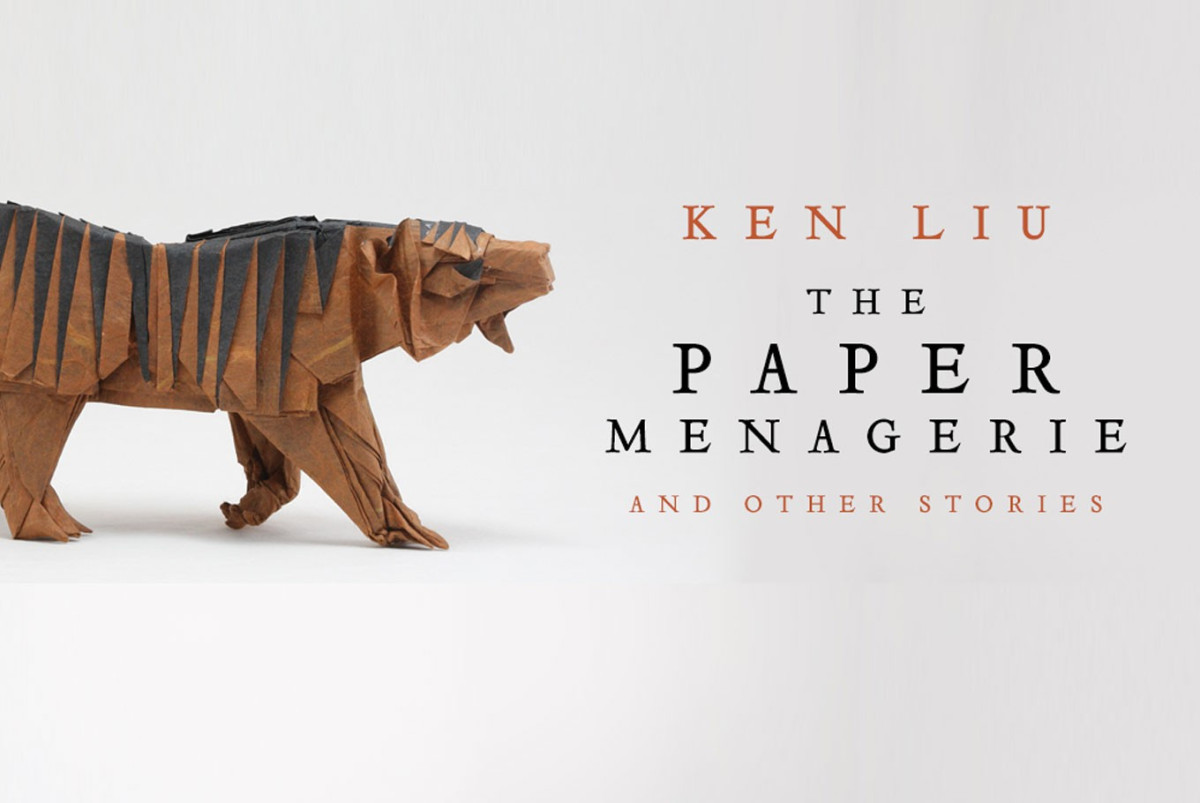

Speculative Fiction Goes for The Heart: Ken Liu’s The Paper Menagerie

Words By Mark Galarrita

When I first started to write, I tried and failed to emulate authors who never wrote, or probably cared, about people from my background. This meant a period in my life where I dabbled in writers whose prose was often terse and morose, mostly male and white. These were also the few books frontloaded to me in school and bookstore displays, described as the ‘literary canon.’ I supposed that to exist in a publisher’s market, you had to brand yourself to a specific genre to even get onto a bookshelf. So I read and tried to figure out what kind of writer I would end up being. Would I become a science fiction writer like Heinlein or a second world fantasy creator like Tolkien? Did I want to write realist stories, or would I only want to do role-playing games for the rest of my life? For years I experimented with different novels, plugging away and going nowhere fast.

But it wasn’t until I read Ken Liu’s The Paper Menagerie that I was shown a gateway to a broader world of speculative fiction, one that tugged at me to read it again, and again—studying sentences and scenes to find out one thing: how did Ken get this story so right? In the opening lines, Liu brings the reader in with an emotional pull before quickly moving into the fantastical:

One of my earliest memories starts with me sobbing. I refused to be soothed no matter what Mom and Dad tried.

Dad gave up and left the bedroom, but Mom took me into the kitchen and sat me down at the breakfast table.

“Kan, kan,” she said, as she pulled a sheet of wrapping paper from on top of the fridge. For years, Mom carefully sliced open the wrappings around Christmas gifts and saved them on top of the fridge in a thick stack.

She set the paper down, plain side facing up, and began to fold it. I stopped crying and watched her, curious.

She turned the paper over and folded it again. She pleated, packed, tucked, rolled, and twisted until the paper disappeared between her cupped hands. Then she lifted the folded-up paper packet to her mouth and blew into it, like a balloon.

“Kan,” she said. “Laohu.” She put her hands down on the table and let go.

A little paper tiger stood on the table, the size of two fists placed together. The skin of the tiger was the pattern on the wrapping paper, white background with red candy canes and green Christmas trees.

I reached out to Mom’s creation. Its tail twitched, and it pounced playfully at my finger. “Rawrr-sa,” it growled, the sound somewhere between a cat and rustling newspapers.”

Published in Fantasy and Science Fiction magazine in 2011, there wasn’t a single spectacular sword or spaceship abound. It was a fantasy, coming-of-age, first-generation Asian-American immigrant story—the first I had seen. A story that made me cry. A story that made me want to plunge into the depths of what Liu did. I wanted to study how a story that wasn’t quite hard science fiction or fantasy (SF/F) could go on to deservedly win the Hugo, Nebula, and other accolades. It made me go out and scrounge for more of Liu’s work—but more importantly, it made me want to read others in the community like him and write to, hopefully, join them one day.

My false impression of the SF/F community was that it only wanted tomes. While stories set in the worlds of Lewis, Tolkien, or Martin are impressive, they weren’t necessarily what I wanted to write about at the moment. Because of Liu’s work, I saw that one can experiment with second-world fantasy, but it was okay to branch out with things like speculative immigrant tales. Pigeonholing yourself is a myth; what counts is that you’re a writer who can tell a coherent story, regardless of whether it involves a character from Greenwich Village or a Goblin Kingdom. Liu’s ability to weave short- and long-form characters that reach for the heart and mind showed me that people from my background mattered. His continued success in the industry has shown me that we could fit into this literary community without having to write a gloomy narrative.

The required reading list for young writers must include contemporary and classical speculative works. Not only are there lessons of craft (character, pacing, and plot to name a few) but they’re also gateways to worlds beyond our own. And they’re fun; is that not what we look for in compelling stories? Dismissing these literary narratives as ‘genre fiction’ only walls off experiences for readers who are on the periphery; it tells them that yes, you can go ahead and write fairy tales or spaceship drama, but your craft, your projects, will never be taken seriously. Literature is not a monolith, and to dismiss stories for their themes and plot walls off potential communities of readers from forming.Readers and writers should continue to hype up the masters of speculative fiction, such as Kij Johnson, Octavia Butler, Ursula K. Le Guin, or Kelly Link,but also look out for contemporary writers such as Carmen Maria Machado, Emma Torzs, Vina Jie-Min Prasad, Rebecca Roanhorse, Izzy Wasserstein, Alyssa Wong, Alexandra Manglis, Elly Bangs, Daniel Jose Older, Shweta Adhyam, and Stephanie Malia Morris. These writers are among others who are being published in speculative journals such as Fireside, FIYAH, Strange Horizons, and Uncanny Magazine. There are lessons to be gained from the various techniques of craft that come from both realism and speculative fiction. I believe both genres attempt to unveil, or attempt to explain, the complex wonder, beauty, sadness, and magic of life. The speculative can reach the heart as gracefully as a beautiful poem or novel—all it takes is patience and a bit of imagination.